|

| [AlJazeera] |

| Abstract The current crisis in the Central African Republic began well before the Seleka coalition seized power in March 2013. The current security crisis is the culmination of a crisis dating back to the ten-year rule of General François Bozizé, combined with a socio-economic crisis that pre-dates his time in power. Socio-economic decline beginning in the late 80s, a missed move to democracy in the 1990s (out of the five post-independence presidents, three, including the most recent, have been military leaders); poor structural governance during the first decade of the 21st century and a predilection for rule by force have left CAR where it is today: in free-fall. |

Behind the security crisis: the economy

It is perhaps a grim irony that, economically, Bokassa’s brutal rule might now be looked on as something of a golden age. Indeed, since then the country's economy has been in perpetual decline. From the late 1990s to the present day, the number of foreign companies operating within the country has fallen from 250 to 25 and, in 2012, on the eve of the current crisis, there was just one mining company still prospecting there. It was looted during the Seleka insurgency and has since ceased activities, which were in any case purely exploratory. Although leaders of the Central African Republic have consistently extolled the mineral wealth of the country, the mining sector has never really existed. There has never been industrial mining in the Central African Republic: gold and diamonds are produced on an artisanal scale, and thus not only represent very small volumes in comparison with other producers across the continent but have also remained largely outside state control.

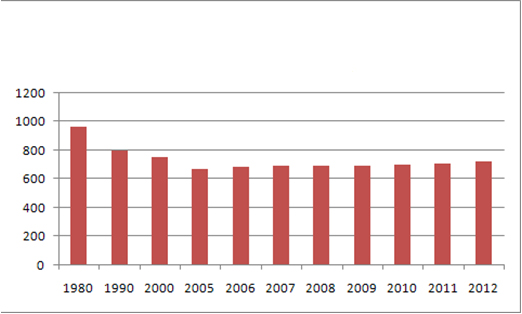

Commercial crops (cotton, coffee, etc.) have never regained their former levels of production. Subsistence farming is the only means of survival for the vast majority of the rural population. Forestry is another extractable resource, but forestry companies present in CAR can be easily counted and their operating costs make them uncompetitive in the international market. As investors withdraw, the public sector has become the largest formal employer in the country (although it is still modest, with only 18,000 employees). The gradual contraction of productive activity and disinvestment has allowed the informal economy to grow and hasresulted in socio-economic indicators which are below the average for the continent. This is true for GDP per capita (which fell from 963 USD in 1980 to 722 USD in 2010), life expectancy (which roseby just one year, to 49, between 1990 and 2012), duration of education and infant mortality. On UNDP’s Human Development Index, the Central African Republic ranked 180th out of 187 countries in 2013.

This deep economic crisis was slightly offset by external aid and particularly foreign support to guarantee the payment of wages. Despite the economic downturn, budget support from various sources (World Bank, African Development Bank, European Union, etc.) enabled Bozizé's regime to largely honour public sector wages, which are the safety net of the economy inthe capital, Bangui. The economic reversal in the Central African Republic can, to a large extent, be explained by the corruption and negligence of successive leaders. The poor governance of the Patassé (1993-2003) and Bozizé (2003-2013) regimes actively drove investors away, while weakening state institutions. By constantly changing mining regulations and trying to take advantage of extractive companies before they had even discovered anything, these regimes have kept the extractive sector at an absolute standstill and built up a bad reputation: coupled with the high costs of prospecting, owing to the country’s remoteness and lack of infrastructure, numerous disputes have convinced investors in the extractive sector to stay well away from the Central African Republic.

GDP per capita

The silent economic disaster was supplemented by a political crisis. After a honeymoon period, François Bozizé’s administration reached crisis point during his second term, which proved one term too many. The fraudulent elections of 2011 may have brought the general back into power but they also created discontent both inside and outside his regime, thereby weakening it. The complete marginalisation of the opposition at the 2011 polls encouraged them to band together, while Bozizé used the elections to bring members of his close circle into political power and tightened control byan ethno-familial group, the Gbaya. This political strategy raised suspicions a constitutional change was being planned to allow a third term for President Bozizé – a fear which created significant tensions within his own camp and probably played a role in the unification of the armed groups in the north-east.

The weakening of the economic base of the state – i.e. taxation - and the weakening of the security apparatus happened in parallel and were the triggers for the security crisis at the end of 2012. The arrival of Seleka on the outskirts of Bangui and their capture of the city in March 2013 were made possible by a gradual and visible decline of the regime, which had previously managed to contain the armed groups in the north-east through a combination of negotiations and use of force by friendly powers (namely France in 2007, and Chad and Sudan as part of the tripartite force in the Vakaga region). However, the efforts of these allies dropped away at the start of 2013.

A religious conflict without religious demands

The root of the current violence lies in the disruption of the internal politics of the Central African Republic. Since independence, the circles of power have been dominated by Christian ethnic groups (Gbaya, Yakoma, Sara, etc.). Successive Presidents (Dacko, Bokassa, Kolingba, Patassé and Bozizé) have all been Christian, although two of them (Bokassa and Patassé) converted for opportunistic reasons. The Muslim population is historically in a minority, yet dominates the Northern provinces, including Vakaga, which, during the colonial era, was seen as the extreme periphery of the country. Therefore, Seleka gaining power was a shock, upsetting a political system that revolved around a political class which represented the ethnic groups from the west and centre, as well as traditional military power. This coalition of armed groups from the north-east together with disaffected Chadian and Sudanese militia disrupted the Central African Republic’s balance of power by introducing marginalised Central Africans and armed foreigners not just to Bangui but also to areas where they had been previously unknown, such as the west. (1) The anti-Seleka reaction is also largely a result of a clash of cultures between the Sahelian populations and the populations from the savannah. This dual political and religious power switch has been widely described by President Bozizé as an Islamist conspiracy. But this rhetoric would have had no effect on the masses if it weren’t for the brutalities of the Seleka militia in the ethnic stronghold of the former president and in Bangui itself.

The abuses committed by Seleka in Bangui and the western prefectures from May 2013 onwards provoked a violent defensive response. Initially directed in a focused manner against Seleka insurgents, these self-defence groups called anti-Balakas (anti-AK47-bullets) swiftly attacked the Muslim communities in western cities and assimilated Muslims more broadly with Seleka. This assimilation was encouraged by the defunct Bozizé regime’s demonization of Seleka and by the suspicious closeness of certain Muslim merchants to Seleka in Bangui. (2)

Nevertheless, the anti-Muslim fever which appears to have gripped parts of the country has deeper roots than simply opposition to the Seleka. It is significant that two groups within the Muslim population have been particularly targeted: city merchants and Fulani herders in the bush. This reflects a longstanding resentment between herders and farmers, as well as resentment towards the dominance of Muslims in trade. The latter do indeed play a key role in this sector both in Bangui and in the provinces and appear “rich” within the overall context of mass poverty. The systematic looting of their shops in the cities held by anti-Balaka groups symbolises an opportunistic violence that enables the perpetrator to seize the wealth of others and easily dispose of those to whom he owes money.

The cycle of violence set in motion a process of radicalisation on both sides: faced with the threat of anti-Balaka forces, Fulani pastoralists have joined the ranks of Seleka and carried out reprisals; in Bangui, demonstrations often degenerate into mob violence towards Muslims and anti-Muslim sentiment predominates as a kind of revenge against those who got their hands on the capital in 2013. We are seeing significant population movements: foreign and national Muslims are leaving the Central African Republic, moving into Chad and Cameroon, while others are following Seleka as they retreat to the east. The Muslim population in Bangui has decreased by about 90% and is living under siege in some neighbourhoods. The violence resonates throughout the country, resulting in preemptive departures (including from cities that were not occupied by anti-Balaka groups) and presenting humanitarian agencies with the following dilemma: help Muslim communities to depart from the west or keep them there and have to ensure their safety and food supply. A de facto religious partition of the country should not be ruled out as the demographics of the country are restructured.

The challenge for the 3rd transitional government: the existence of the Central African State

The President, Catherine Samba Panza, who was appointed by the National Transitional Council at the end of January 2014, is facing a massive challenge, that of preventing the disappearance of the Central African Republic as a state. Her programme has already been defined as the transition roadmap, drafted in the last quarter of 2013 and identifying all the tasks required to get the country back on its feet (reconstruction, emergency aid, management of ex-insurgents, preparing for elections, etc.). But nothing in this roadmap has been implemented and the obstacles are huge. The security crisis is far from settled: parts of the country are under the control of Seleka and parts under anti-Balaka forces who also challenge the authority of the transitional government in Bangui The transitional government has no means of action because it has no money. The coffers of the treasury are completely empty and public sector wages are now five months in arrears. The transitional government is currently seeking donors to allow it to pay public servants and reboot the administration, without which the reconstruction and the elections scheduled for 2015 will not take place. If emergency assistance is not found promptly, the government risks being both ineffective and unpopular.

Differently-motivated foreign military interventions

Chad and France both have troops in Central Africa. Although variable, the French military presence has been almost uninterrupted since independence, while the Chadian presence dates back to the late 1990s. Chadian troops have been present both within the African Union mission (the MISCA) and in their own right. Some have been posted in the north-east of the Central African Republic, in the prefecture of Vakaga, for several years following an agreement with Bangui, while other troops, sent to evacuate Chadians, are present without permission. After maintaining a military presence to secure Bangui airport at the time of Seleka’s victory, France decided to launch a disarmament operation, known as Operation Sangaris, which began in early December and now totals some 2000 men.

The two countries have very different motivations for maintaining a military presence in the Central African Republic. For Chad, it is a question of defending both its security and economic interests. Two of its main priorities are to avoid the Central African Republic becoming a base for an armed opposition and to use itsterritory for the migration of livestock in the dry season. Some also believe that Chad hopes to make oil development impossible in the north, notwithstanding that the presence of oil is only a possibility and not a certainty.

There is no significant security or economic interests for France. Its military already has two support points within the region (Ndjamena and Libreville), the few French companies still in the Central African Republic no longer do significant business and the French community is now reduced to a minimum. The intervention is more a result of pressure from the humanitarian lobby (most international NGOs in the Central African Republic were French in 2013) and discreet requests from certain countries within the region.

Although linked through other military operations, French and Chadian troops have not found themselves on the same side in Bangui. Initially sent to disarm Seleka, French troops could only observe the proximity between Seleka and the Chadian troops. This proximity has made the Chadian troops very unpopular, generated some tensions between French and Chadian soldiers, led to an incident between Chadian and Burundian troops within the MISCA and, ultimately, to the withdrawal of the Chadian troops from MISCA in April. There is, therefore, no coordinated international intervention in Central Africa, just discrete interventions lacking in consistency.

Towards an end to the crisis

As noted by the Secretary-General of the United Nations in his latest report, there is no quick solution to the Central African crisis. The depth of its roots makes it impossible to envisage a short crisis. The security collapse must first be contained to be able to then consider rebuilding state structures and, in particular, rebuilding a job-creating economy. The major challenge in the Central African Republic at this time is to quickly restore an economic system which allows the majority of the population to earn an honest living. This involves prioritizing the economic recovery in the peace building agenda and carrying out a critical exercise to understand why development aid has failed in this country.

_____________________________________________________________

Copyright © 2014 Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, All rights reserved.

*Thierry Vircoulon is the Project Director for Central Africa at International Crisis Group.

Endnote:

(1) For more on the emergence of Seleka and the seizure of power, see the Crisis Group report “The priorities of the transition", 11 June 2013.

(2) The taking of Bangui by Seleka was warmly welcomed by certain merchants at the city’s main market (PK 5), which was heavily reliant on the Chadians. Business relationships were quickly established between the Seleka militia and these traders to the extent that the PK5 became the main place of concealment for the goods looted by Seleka (in particular cars) and for trafficking in gasoline. This was an open secret.