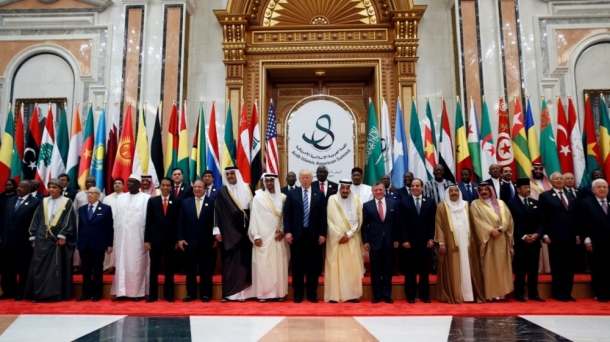

The new approach of the U.S. foreign policy toward the Middle East has increasingly pivoted around possible ways of fighting radical groups with various denominations. The Riyadh Summit, hosted by Saudi Arabia May 20 and 21, 2017, displayed an ironic moment in international politics while squeezing various forms of opposition, resistance, and political violence into the stigmatizing label of “terrorist” groups and widening the scope of their suspected “supporters”. It also solidified Donald Trump’s declared campaign against “radical Islamic terrorism”, as a step forward to defeating the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, known as ISIS) and its subordinates across the region.

Consequently, the new Gulf conflict showcases how certain global or regional powers may resort to the counterterrorism discourse to stigmatize and pressure certain governments like Qatar, and to position their realist drive for power politics against regional calls for preserving certain moral politics and Kantian ethics. This discourse has become instrumental in pushing world politics onto the edge of political immoralism. However, this shift seems to have derived its momentum in managing international politics from some faulty assumptions.

An International Groupthink Moment

The main highlight of the Summit was the need for a firm stand against suspected ‘terrorist’ groups and their ‘backers’. While addressing leaders of fifty Arab and Muslim nations, Trump trumpeted the plight of violence in the Middle East and promoted his new war-on-terror discourse. He argued that “more than 95 percent of the victims of terrorism are themselves Muslim. We now face a humanitarian and security disaster in this region that is spreading across the planet. It is a tragedy of epic proportions. No description of the suffering and depravity can begin to capture its full measure.” (1)

Effectively, disseminating fear transformed Trumps’ power from leading to dominating; and his strategic interests became l’ordre du jour of the talks. The Summit provided an adequate platform for Trump to reconfigure international relations with a Machiavellist twist, and enabled a great power to expand its will upon fifty weak states that are struggling for power and influence in regional and world politics.

Trump also sought some naturalization of his controversial discourse of "radical Islamic terrorism", the main pillar of his electoral campaign, in a public forum near Mecca and Medina, the two holly sites of Islam. He hoped the Summit would be “the beginning of the end to the horror of terrorism!" (2) His strategy led to the formulation of an overlapping consensus among the attendees over the intended eradication of ‘terrorists’ and the moral duty of taking revenge and bringing justice.

American philosopher John Rawls explains that an overlapping consensus on principles of justice can occur despite "considerable differences in citizens' conceptions of justice provided that these conceptions lead to similar political judgments.” (3) Ultimately, Trump secured enough support for his counterterrorism policy since “America is committed to adjusting our strategies to meet evolving threats and new facts… We are adopting a Principled Realism, rooted in common values and shared interests. (4)

In retrospect, the Summit’s overlapping consensus indicates two main shortcomings: ill-informed groupthink and hyper-counterterrorism paradigm.

1. Uncontested Groupthink

With the exception of Qatar, the dominant groupthink which reigned supreme in the Summit ushered to an overcapitalization in Trump's ego and future policies. Groupthink can be defined as a “mode of thinking that persons engage in when concurrence-seeking becomes so dominant in a cohesive in-group that it tends to override realistic appraisal of alternative courses of action.”(5) The mutual fear of Iran and political Islam, energized by a hard-power-based framework of counterterrorism, and the resentment of Aljazeera’s progressive discourse seem to have blocked critical thinking about the feasibility of Trump's grandiose promise of eradicating ISIL and other forces of extremism in the region.

This uncontested groupthink derived its conformity from an illusion of invulnerability when the Gulf-Arab-Muslim leaders were embedded in an inflated certainty that they had made the right decision. The driving force behind this illusion of invulnerability was their belief and investment in Trump’s statements and intentions being the ‘powerful’ leader of the most powerful nation in the globe. Memorable cases of groupthink include the Bay of Pigs disaster that led to the failed invasion of Castro's Cuba in 1961 and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.

The Summit scenario demonstrates several typical trends of groupthink as devised by Irving Janis in his book “Victims of Groupthink”: 1) excessive optimism based on the illusion of invulnerability; 2) unquestioned belief in the morality of the group; 3) closed-mindedness; 4) stereotyping those who are opposed to the group as weak, evil, or biased; 5) self-censorship of ideas that deviate from the apparent group consensus, 6) illusions of unanimity among group members, silence is viewed as agreement; 7) direct pressure to conform placed on any member who questions the group, couched in terms of "disloyalty"; and 8) role of mind-guards a self-appointed members who shield the group from dissenting information.

During the two-day Summit, Gulf-Arab-Muslim leaders sensed high group cohesiveness while avoiding speaking against certain resolutions and decisions, and maintained friendly relationships in the group. Trump argued that “we can only overcome this evil of the forces of good are united and strong—and if everyone in this room does their fair share and fulfills their part of the burden.” (6)

The Summit also indicated a dilemma of de-individuation when group cohesiveness became more important than individual freedom of expression or opposition with the exception of the Qatari delegation. This moment was instrumental in deciding new lines of demarcation of an ‘in-group’-versus-‘out-group’ animosity. Two weeks later, the animosity translated into an air and land blockade imposed by Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Bahrain, with the blessings of Egypt, against Qatar. Trump also retaliated against Doha as he wrote in a tweet, "During my recent trip to the Middle East I stated that there can no longer be funding of Radical Ideology. Leaders pointed to Qatar - look!"

However on Capitol Hill, several congressmen expressed concern over Trump's position vis-à-vis the Gulf conflict. Ruben Gallego (D-AZ), a member of the House Armed Services Committee, sharply criticized Trump's statement; "This situation is complex, like many diplomatic situations, and showcases how uniquely unqualified Donald Trump is in securing the best interests of the United States when it comes to foreign policy and national security." (7)

2. The Prejudice of Counterterrorism

The Riyadh Summit ran the risk of being encapsulated in a hyper counterterrorism paradigm as a myopic generalization of various oppositional, resistant, radical, and violent groups in the Middle East. However, it derives its guidance from an open-ended debate around the definition of ‘terrorism’. There is still constant fluidity of its meanings as a precursor for deciding promising counterterrorism strategies. Most scholars like Sue Mahan consider it to be an “ideological and political concept”; and that politics, by its nature, “is adversarial, and thus any definition evokes adversarial disagreement.” (8)

As a backdrop, the growing counterterrorism paradigm has been subjected to deliberate political and ideological manipulation vis-à-vis certain groups and suspected ‘harboring’ governments. For example, the controversial 13-demand list, including the elimination of Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood and condemning Qatar by association, represents a marriage of political convenience between Trump and a number of regional leaders including Egypt's Abdel Fatah el-Sisi and Israel's Benjamin Netanyahu.

Such politicization of counterterrorism reveals more than one irony in the supposedly-moral condemnation of several movements and political figures in recent history. For nearly three decades, several U.S. administrations categorized Nelson Mandela’s political party, the African National Congress, a “terrorist group” in South Africa, and Mandela’s name remained on the U.S. terrorism watch list till 2008. By the same token since 1964, the United States and Israel considered the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) to be a “terrorist organization” until the Madrid Conference in 1991, when the Bush-41 White House opted for its engagement in the peace process.

The West’s merger of strategic interests, ideology, and counterterrorism remains vital in managing its relations with the rest of the world. In his joint news conference with the Emir of Kuwait Sabah al-Ahmed al-Sabah at the White House, Trump echoed once again his call on his “GCC and Egyptian allies to focus on our commitments at that Saudi Arabia Summit to continue our joint efforts to drive out and defeat terrorists. Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Egypt are all essential U.S. partners in this effort.” (9) However, the use of counterterrorism as the new currency of international relations implies an oversimplification of different forms of threats.

Reflective Recollection of Political Violence

Since the turn of the new century, there has been a growing security nightmare due to the upsurge in deadly attacks worldwide. The worst year for terrorism was 2014 with 93 countries experiencing an attack while 32,765 people were killed. In 2015, there were 274 known terrorist groups that carried out attacks at various locations, For instance, ISIL-affiliated groups undertook attacks in 28 countries in 2015, up from 13 countries in 2014. (10) The global economic impact of these violent attacks reached U.S. $89.6 billion each year in 2014 and 2015. (11)

According to the 2016 Global Terrorism Index, 50 per cent of all terrorist attacks occurred in countries in the midst of an internal conflict. A further 41 per cent occurred in countries whose governments were militarily involved in an internationalized conflict including the United States and Britain. More than a decade ago, terrorism analyst Daniel Wagner argued for a pivotal moment in history in the post-9/11 era; and “how the world's civilized nations collectively fight against terrorism will determine the future course of international relations. (12)

This shift has threatened global security and prioritized the formulation of counterterrorism strategies at national and international levels. Still, it begs the question about the true outcome of the 16-year ‘War on Terror’, initiated by the Bush administration in 2001 through the use of military force, in formulating a nuanced approach towards political violence to help guide the policies of the Trump administration.

However, the conceptualization of terrorism, as an ideological and political construct, still blurs the political and immoral/moral boundaries between different forms of political violence at the intersection between power and resistance. It has also perplexed scholars and policy makers alike with the challenge of separating “terrorism” from simple criminal acts, open war between ‘consenting’ groups, and acts that clearly arise out of mental illness. These considerations have raised new questions about the nuances and potential impact of various counterterrorism policies adopted by Great Powers like Trump’s America as well as various international bodies like the United Nations, the European Union, NATO, and others.

‘Terrorism’ as an Empirical Dilemma

Either as concepts or fields of empirical research, ‘terrorism’ and ‘counterterrorism’ are still unsettled narratives of the politicization of violence between militant groups and security-driven governments. Military historian Caleb Carr argues that international terrorism is simply “the contemporary name given to, and the modern permutation of, warfare deliberately waged against civilians with the purpose of destroying their will to support either leaders or policies that the agents of such violence find objectionable.” (13)

Consequently, nations and international organizations are still debating the existing 109 definitions of terrorism with no consensus on a particular conceptualization. Sue Mahan of the University of Central Florida points out that “the adversarial and political postures embedded in the practice of terrorism make it unlikely that a universally-accepted definition or a widely-shared strategy for controlling it will soon emerge.” (14)

The following sample of definitions captures the disparity and variations of what makes ‘terrorism’ within certain agencies and institutions that should be supposedly working in harmony with similar tools and concepts. The U.S. State Department conceives ‘terrorism’ as “premeditated, politically motivated violence perpetrated against noncombatant targets by sub-national groups or clandestine agents, usually intended to influence an audience.” However a few miles away in Washington, the Department of Defense, or Pentagon, adopts “the calculated use, or threatened use, of force or violence against individuals or property to coerce or intimidate governments or societies, often to achieve political, religious, or ideological objectives.”

Furthermore, the United Nations defines ‘terrorism’ to be “any act intended to cause death or serious bodily injury to a civilian, or to any other person not taking an active part in the hostilities in a situation of armed conflict, when the purpose of such act, by its nature or context, is to intimidate a population, or to compel a government or an international organization to do or to abstain from doing any act.” (15) As terrorism studies critic Lisa Stampnitzky points out, “Terrorism researchers have characterized their field as stagnant, poorly conceptualized, lacking in rigor, and devoid of adequate theory, data, and methods.” (16)

Avoiding Dirty Politics

Ironically, the polarization and ideologization of ‘terrorism’ have inspired certain institutions to avoid dealing with ‘state terrorism’ at all. For instance, the Institute for Economics and Peace which publishes the Global Terrorism Index narrows ‘terrorism’ to be “an intentional act of violence or threat of violence by a non-state actor,” and “the perpetrators of the incidents must be sub-national actors. This database does not include acts of state terrorism.” (17)

Terrorism studies scholar Neil J. Smelser argues that “appreciating the dynamics of ideological elaboration also permits us to grasp its dynamic character. Ideology is not a thing, fixed in time, but rather a continuous process of development and rationalization, forever adding, forgetting, explaining, and adapting to the world as new events and situations – particularly unanticipated ones – arise.” (18)

Consequently, this selectivity of what goes into the category of ‘terrorism’ undermines the formulation of adequate counterterrorism concepts and strategies. It also overshadows the subtle connection between certain doctrinaire public policies and the debate of national security matters in the public sphere.

The tacit ideological considerations in categorizing certain acts of violence as ‘terrorism’ have affected another parallel. Some ideological imperatives have impacted the construction of ‘terrorism’ history since terrorism studies were institutionalized in the 1970s. Liberal philosopher Noam Chomsky wittingly points to the irony of ‘terrorism’ inclusion/exclusion; “You have to find a definition that excludes the terror we carry out against them, and includes the terror that they carry out against us. And that’s rather difficult.” (19)

Terrorism Studies: Anecdotes or Science Knowledge?

In a post 9/11 world, the political conceptualization of “terrorism” has claimed a social science gloss amidst some controversy. Richard Norton professor of sociology at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point and author of one of the first annotated bibliographies on the terrorism literature, suggests that the study of terrorism is populated in part by people who were “failed scholars in other areas” who yet “publish books by the dozen and make very little substantive contribution to the field.” (20) Other critics have argued that “terrorism falls between the chairs”; (21) while the science of terror has been conducted “in the cracks and crevices which lie between the large academic disciplines.” (22)

Yet, another parallel remains a useful link between ideology and the construction of terrorism history. Certain studies have addressed four waves of ‘terrorism’: 1) Anarchist Wave [1880s-1910s]; 2) Anti-Colonial Wave [1920s-1960s], 3) New Left Wave [1960s- 1990s], and 4) Religious Wave [1979 Iran hostage crisis-present]. With the advocacy of the Clash-of-Civilizations camp, the door has opened wider to overload the current wave with more political, cultural and ideological crossfire lines of difference, mistrust, and confrontation.

Consequently, there is growing manipulation of counterterrorism, as a grand narrative, under the banner of a ‘moral’ and ‘security’ imperative. However, any counterterrorism strategy remains misguided unless the global community finalizes a mainstream and nuanced definition of terrorism.

Advocacy of Neo-Machiavellism

The Gulf conflict reveals how certain international and regional powers exploit it as a blanket statement of neo-Machiavellian politics in painting various trends of resistance politics with the brush of terrorism, cornering certain nations, and ultimately enriching the realist tactics of power politics. As former coordinator of the Obama administration's Middle East policy Robert Malley put it, "clearly, the Saudis and the Emiratis felt they had someone in the White House who would take their side." (23)

As Trump and some Gulf leaders promote their narrative of eradicating ‘terrorism’, one should reflect deeply on the underpinnings of counterterrorism politics, and distinguish between two approaches of any intended strategy: 1) a literal approach that showcases the security measures in place to protect innocent lives and contain extremism and radicalization; and 2) a propagandistic approach positioning the counterterrorism discourse as a weapon of managing international relations and servicing their system of power and aspirations of realpolitick with an extra dose of neo-Machiavellism.

_______________________________________________

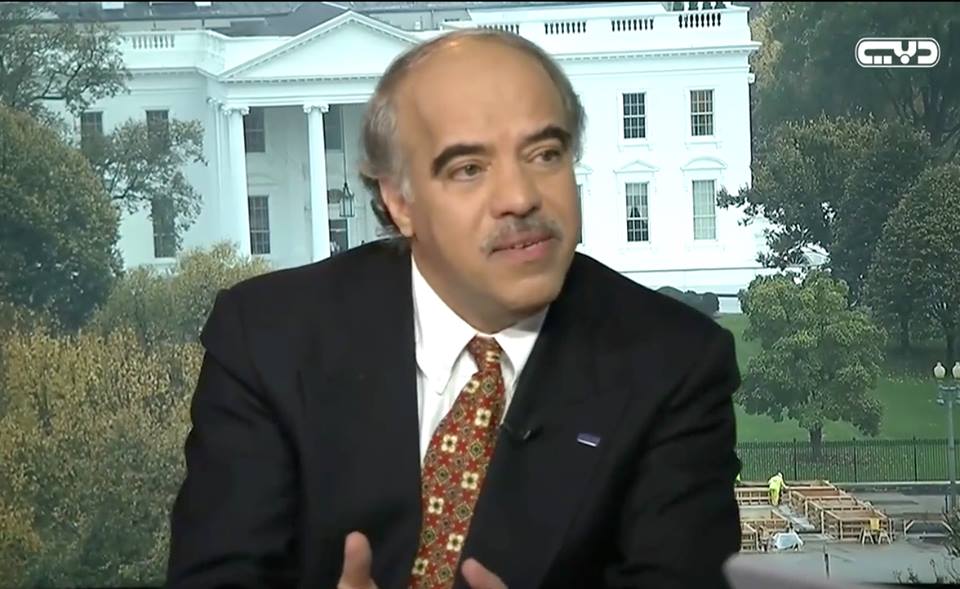

Dr. Mohammed Cherkaoui is professor of Conflict Resolution at George Mason University in Washington D.C. and former member of the United Nations Panel of Experts.

1- Uri Friedman and Emma Green, “Trump's Speech on Islam, Annotated”, The Atlantic, May 21, 2017

https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/05/trump-saudi-speech-islam/527535/

2- Uri Friedman and Emma Green, “Trump's Speech on Islam, Annotated”, The Atlantic, May 21, 2017

https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/05/trump-saudi-speech-islam/527535/

3- John Rawls, A Theory of Justice. (Revised Ed.) Harvard University Press, 1971, 1999, p. 340.

4- Uri Friedman and Emma Green, “Trump's Speech on Islam, Annotated”, The Atlantic, May 21, 2017

https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/05/trump-saudi-speech-islam/527535/

5- Irving Janis, "Groupthink", Psychology Today. November 1971. 5 (6): 43–46, 74–76.

6- Uri Friedman and Emma Green, “Trump's Speech on Islam, Annotated”, The Atlantic, May 21, 2017

https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/05/trump-saudi-speech-islam/527535/

7- Ashley Killough and Jeremy Herb, “Key senators pass on reacting to Trump Qatar tweets”, CNN, June 6, 2017

http://www.cnn.com/2017/06/06/politics/congressional-reaction-qatar-trump-tweets/index.html

8- Sue Mahan, “What is Terrorism? “ in Terrorism in Perspective, edited by Sue Mahan and Pamela L. Griset , Sage Publications, Third Edition 2012, p. 3

9- The White House, Remarks by President Trump and Emir Sabah al-Ahmed al-Jaber al-Sabah of Kuwait in Joint Press Conference, September 7, 2017

10- Institute for Economics and Peace, “Global Terrorism Index 2016: Measuring and Understanding the Impact of Terrorism”

http://economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Global-Terrorism-Index-2016.2.pdf

11- Institute for Economics and Peace, “Global Terrorism Index 2016: Measuring and Understanding the Impact of Terrorism”

http://economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Global-Terrorism-Index-2016.2.pdf

12- Daniel Wagner, “Terrorism's Impact on International Relations”, IRMI, March 2003

https://www.irmi.com/articles/expert-commentary/terrorism's-impact-on-international-relations/

13- Caleb Carr, The Lessons of Terror: A History of Warfare Against Civilians, Random House, 2002, p. 6

14- Sue Mahan, “What is Terrorism? “ in Terrorism in Perspective, edited by Sue Mahan and Pamela L. Griset , Sage Publications, Third Edition 2012, p. 1

15- Article 2(b) of International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism, May 5, 2004)

16- Lisa Stampnitzky, Disciplining an Unruly Field: Terrorism Experts and Theories of Scientific/Intellectual Production, Quol Sociol December 14, 2010

17- Institute for Economics and Peace, “Global Terrorism Index 2016: Measuring and Understanding the Impact of Terrorism”

http://economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Global-Terrorism-Index-2016.2.pdf

18- Neil J. Smelser, The Faces of Terrorism: Social and Psychological Dimensions, Princeton University Press, 2007. p. 79

19- Noam Chomsky, Gilbert Achcar, Stephan R. Shalom,” Perilous Power: The Middle East and U.S. Foreign Policy; Dialogues on Terror, Democracy, War”, and Justice, Routledge, 2009

20- Hoffman, R. P. (1984). Terrorism: A universal definition. Unpublished M.A., Claremont Graduate School.

21- A. Merari, (1991). Academic research and government policy on terrorism. In C. McCauley (Ed.), Terrorism research and public policy. London: Frank Cass and Company, p. 88

22- A. Silke, (2004). Research on terrorism: Trends, achievements, and failures. New York: Frank Cass, pp.1-2

23- Mark Landler, “Trump Takes Credit for Saudi Move Against Qatar, a U.S. Military Partner”, The New York Times, June 6, 2017

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/06/world/middleeast/trump-qatar-saudi-arabia.html?mcubz=0