While visiting the military base of Hmeymim during his Middle East tour, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced the withdrawal of the Russian military groupings from Syria. He also stated a limited contingent of Russian troops would remain in Tartus and Hmeymim in order to maintain stability in the country. This shift in the Kremlin’s Syria policy was announced on the eve of the presidential election campaign, when Russia continues not only to maintain its military positions in Syria, but also to take an active part in shaping the future of the Syrian crisis. However, the gradual transition from a state of armed conflict to a political dialogue and the discussion of a post-crisis arrangement of Syria, as was the case in Sochi, raise the question of how Russia will maintain its influence in the region. Apparently, Moscow's actions in Syria seem to fulfill the official function of solidifying Putin’s chances in the upcoming presidential bid. They should also create the most favorable conditions for the Russian leadership to guide the negotiating process of Syria’s future. The question arises: will Russia keep its promise this time, unlike in March 2016, since the military situation in Syria has changed markedly?

Still not a Withdrawal

The completion of the operations to liberate first the ideological center of the Islamic state, Mosul, and then the political one, Raqqa, by the U.S.-led anti-terrorist coalition forces, as well as the successes of the Syrian army in Deir el-Zor and in the east of Syria, could be regarded as a victory over ISIS.

It is highly expected that Russia, Iran, and Turkey will start joint operation against "Tahrir al-Sham" in the so-called Great Idlib, then divide it into spheres of influence. As a result, one of the last flash points of conflict Syria will be localized. At least, the Turkish ground operation, "Olive branch", which began in Afrin after coordination with Moscow, will directly affect the situation in Idlib. Since Russia gave a "green light" to the military operation, it could well count on Ankara's additional counter steps in Idlib. In recent weeks, Turkey has been holding back the areas under its control among moderate opposition from full participation in the battles in Idlib province, where the Syrian army launched a large-scale operation to capture Abu al-Duhur from the beginning of January.

After two years of Russian support and the activities of several radical groups in Syria, a significant part of the opposition waned to a large extent. Most of active hostilities has come to an end. After almost seven years of a grueling and bloody conflict, hopes for peace and stability have become much more important than the issues of power and future political order. These dynamics presuppose the importance of deconstructing the declared Russian withdrawal from the armed conflict, but not from the Syrian crisis as a whole.

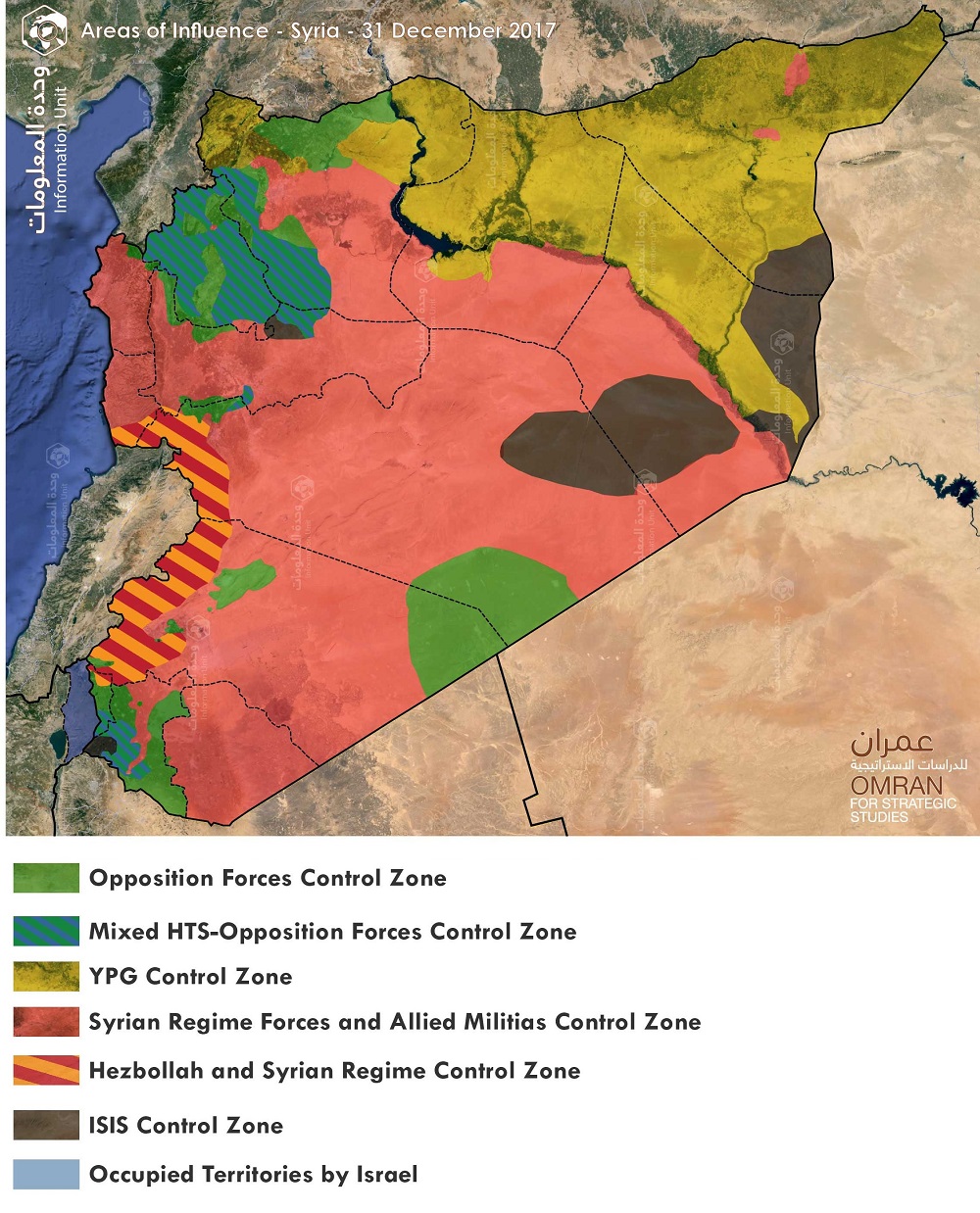

|

| Areas of influence in Syria at the time of the announcement of Russian troop’s withdrawal (Source: OMRAN Center for Strategic Studies 2017) [Al Jazeera] [Al Jazeera] |

During the last months of 2017, Moscow’s diplomatic moves vis-à-vis the Syrian issue seemed quite hectic. While attending the G-20 summit in Danang, Vietnam, President Putin and President Trump made a joint statement arguing that the Syrian conflict had only a political solution, and confirmed their commitment to the Geneva diplomatic process as well as to the principles of the UNSC Resolution 2254. A few days later, Russian minister of foreign affairs, Sergey Lavrov, openly accused the UN member states of being insufficiently active in pursuing the settlement of the Syrian conflict. He also argued that Russia with the assistance of certain regional players, namely Iran and Turkey, should give a new impulse to the process of the political reconciliation.

This statement triggered a heated debate among political analysts on whether Russia was truly interested in preserving the Geneva process. Some of them suggested the Kremlin was aiming at undermining the importance of the Geneva talks and replacing them with the Astana process, guided mainly by regional and relatively pro-Moscow players. Yet, when it comes to the regional players, Russia might also seem inconsistent: instead of proceeding with the Astana talks, it decided to host the Congress of the Syrian national dialogue. While flirting with the Syrian Kurds, Moscow obviously is building up the path of cooperation with Turkey and Iran. Thus, President Putin recently met twice his Turkish and Iranian counterparts Erdogan and Rouhani. It is noteworthy to remember Russia was actively consulting with Israel in the process of establishing the de-escalation zones in southwestern Syria. Yet on November 14, Russian Minister of foreign affairs, Sergei Lavrov, called the Iranian military presence in Syria ‘legitimate’; and countered U.S. officials’ argument that that Moscow secured the withdrawal of the Iranian forces from the Syrian territories near the borders with Israel.

Hostage to the Election Campaign

Moscow’s diplomatic moves seem to have much more logic and consistency with the help of some Western powers. First, it is necessary to consider the internal political component of recent events in Syria. Putin’s announcement of a military victory over the radical groups announced and the withdrawal of the air and land forces from Syria in December 2017 was a successful propaganda move that justified Russia's continued participation in the protracted intrastate conflict in Syria. It was important for the Russian president to launch his election campaign "shockingly”, showing that he crushed the “terrorists” with a powerful blow, hardly shedding any blood and in a foreign territory". Therefore, Putin timed his statement about the defeat of the most combat-capable ISIS forces and the return of the Russian military from Syria "in triumph" on December 11, 2017, the eve of the announcement of his new presidential bid.

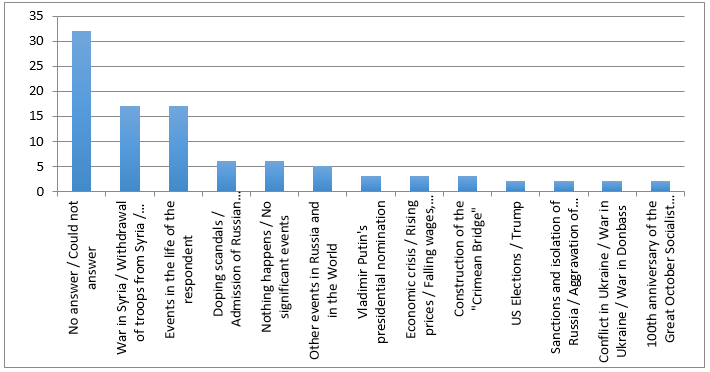

|

| The most important events of 2017 in the opinion of Russians (Source: Levada Center 2017) [Al Jazeera] |

One can argue that all Russia’s actions vis-a-vis the Syrian crisis, including the call at the Valdai forum in October 2017 to hold the Congress of the Syrian people in Sochi not far away from the scheduled date of the presidential elections, are determined precisely by the domestic political agenda. Although the Russian leadership has publicly announced the fulfillment of the tasks set in Syria and the elimination of the terrorist threat, there is still a serious risk dragging Russia into a Syrian war. In the event of any escalation of the situation, it would be difficult for Moscow to justify to its citizens the need to strengthen the aviation or land forces. President Putin has already declared victory over ‘terrorists’. However, the military reinforcement order can be made non-public, and would not demand any explanations, since the original size of the Russian force has not been disclosed.

Consequently, Russia’s military participation in the Syrian conflict should not become a burden on Vladimir Putin during his next presidential term. In the eyes of the Russian public opinion, he should approach the presidential elections, scheduled for March 2018, as a peacemaker and victor, in light of his achievement in Syria. Reports about military operations in the field can be replaced by the idyllic pictures of "return to peaceful life", and demonstrate the stability of Moscow's presence in the region. This outlook reinforces the need of the Russian leadership to make maximum efforts to pedal forward the negotiation process and address issues related to the economic reconstruction.

As mentioned earlier, the withdrawal of Russian troops from Syria coincided with the announcement of Putin's election campaign. He made a tactful decision by showing that Syria is not Afghanistan, as the second Chechen war was different from the first one. The Syrian operation was planned short-term, but the plan was not fully executed. Still after two years of Russian military involvement in the Syrian conflict, most Russians consider it justified, while there has been news fatigue of a distant war. In this context, it was important for Putin to play the Syrian card in his campaign, as long as the public opinion remains interested. According to the Public Opinion Foundation, the percentage of those who closely followed the situation in Syria declined from 30 percent to 24 percent between October 2015 and October 2017.

A Depreciating Asset?

Beyond the Russian support, Bashar Assad can consider himself the winner in the ongoing civil war. However, this outcome does not guarantee Moscow comfortable presence in a post-war Syria. In the course of the armed operations, Damascus considered Moscow’s military support to be the most important part of the Russian intervention beyond any diplomatic or political backing. However, with the transition to the post-conflict period, the significance of the military factor would steadily decrease, giving way to the financial and economic aspects of cooperation. This shift calls for better understanding in Moscow.

|

| Vladimir Putin embraces Bashar al-Assad during a meeting in Sochi, Russia. [Al Jazeera] |

By the end of 2017, Russia managed to fulfill the main tasks of its operation set two years earlier in Syria. First, it managed to shift the attention from Russia’s internal economic difficulties in the post-Crimean crisis era to focusing on the foreign policy agenda. The Russian leadership also managed to rally its own popular base and solidifying the unity between the government and the people in a common front against external enemy.

Second, Moscow succeeded in getting out of diplomatic isolation. This shift is best illustrated by the close relationship with the Assad regime. Moscow sent a signal to the world community that the Syrian president could not be simply overthrown. His political destiny could not be addressed outside negotiations with Moscow. Moscow has reemerged out of the perimeters of the West-imposed policy of isolationism.

|

| Attendees depart at the end of a session of the Syrian Congress of National Dialogue in Sochi [Al Jazeera] |

However, the preservation of Syria’s Baath regime, as well as the military bases in Hmeymim and Tartous, does not mean the victory of Russia. Tactical successes have not solved the strategic challenge, something the Russian leadership is trying to address. Moscow has not been able to change the Syrian campaign to mitigate sanctions or amend the position of Western powers toward Ukraine. Furthermore, Russia faces another important challenge: the conversion of its military successes for diplomatic capital. This explains Russia’s need for effective ways to strengthen its future role in the processes of reconstruction and transitional justice.

As a regional and well-involved power in Syria, Hassan Rouhani told Bashar al-Assad in a recent phone call that Iran was prepared to “actively participate in Syria’s reconstruction”. Accordingly, Russia's position in Syria does not seem to have the upper hand, and may find itself obliged to seek new allies in Syria, rather than Tehran or Ankara. The Kremlin has adopted the strategy of accelerating the Syria negotiating process under its control as seen in Sochi early February.

Another factor that has energized the Russian role in the Syrian conflict is the growing a sense of despair after the eight rounds of struggling talks in Geneva since June 2012. Moscow intends to preserve its role at a time when military aid will be valued much less than the financial one. This dynamic remains significant in maximizing the Russian intervention in the Syrian negotiation process.

Formalization of the Negotiation Process

It is now clear that Bashar al-Assad managed to hang to power, while Moscow has eased up international pressure for his removal. There is growing persuasion toward the Baathist regime to participate in a real national dialogue. It will be more difficult with every passing day, primarily due to the increasingly uncompromising position of Damascus, as well as its increasing autonomy from Moscow.

Adviser to the Syrian president Bouthaina Shaaban and Deputy Foreign Minister Faisal al-Mikdad have expressed skepticism about the negotiation process under the auspices of the United Nations early February. Damascus argues that any negotiations with the opposition can take place only after it is "completely disarmed" and provided it "does not interfere in the internal affairs of the country". With such a trajectory of the Syrian position, the intended ‘inclusive’ national dialogue, which should determine the contours of a future Syrian state, turns into another negotiation obstacle between the ‘victorious’ and ‘defeated’ parties. The main disagreement pivots around the definition of limits on the integration of the opposition into the bodies under the control of the Baathists, provided they fulfill the ultimatum demands of Damascus. From a conflict resolution perspective, The Kremlin foresees its role as an intermediary who can influence the regime on the one hand and guarantee the opposition’s interests on the other.

However, where does the Russian diplomacy and the emerging Sochi process fit in the context of the UN-brokered Geneva process? Can Sochi bypass Geneva as it stands as the only platform that can legitimize any status quo in Syria? In diplomatic terms, Russia's influence remains minimal. It has to maintain its support for the UN diplomacy since it was one of the main sponsors of the Security Council Resolution 2254, and put up with the state of affairs, officially and publicly, recognizing Geneva's primary role in the Syrian negotiation process. Ironically, the tactic of the Russian leadership is not to replace Geneva with alternative platforms (for example, Astana), as many experts believe, but to impose its rules of the game in the presence of UN Special Envoy Staffan de Mistura and the participants of the Geneva talks.

This vison was behind the decision to host the Congress of the Syrian people in Sochi January 30 with an almost a replica of the Geneva agenda. The purpose of the Sochi Congress was to demonstrate the superiority of Russian diplomacy, and provide the opportunity to monopolize the Syrian negotiating process. For Russian ordinary citizens who are not familiar in the Syrian complexity cannot differentiate between various Syrian factions, the Congress meant a victory of Russian diplomacy.

Despite all Moscow's efforts, one can argue that the Sochi Congress was a failure rather than a success. Its main problem is the lack of legitimacy. The absence of representatives of genuine Syrian opposition groups hindered the Congress’s credibility and effectiveness, and demonstrated the limitations of Russian diplomatic capabilities. At a prior meeting in Vienna January 26, the Syrian Negotiation Committee was not able to adopt a consolidated decision regarding its participation in the Congress. Out of 34 members, only 10 favored the Russian initiative, including four from the Moscow platform, three from Cairo, and three independent ones), which was enough to block the proposal to boycott the Sochi meeting. The minimum number to ratify any decision is 26 members, according to the rules of the Committee.

The organizers of the Sochi Congress hoped to neutralize the lack of opposition through the participation of UN Special Envoy de Mistura. However, he declined at the last moment an invitation to speak at the meeting. The situation became more complicated when a number of attending delegates refused to vote for the final statement. The arguments were getting heated about the constitutional reforms, which were supposed to be carried out under the auspices of the United Nations. Some participants asserted that the adoption of the constitution is Syria's internal affair and should be implemented without the participation of de Mistura. Kremlin’s special envoy for Syria, Alexander Lavrentiev, argued that the refusal of this formulation would lead to a loss of any hope for the legitimacy of the Sochi Congress. Such an argument did not seem to have affect the delegates’ decision who voted against the final statement.

Probably the main highlight of the Congress was not only Moscow's inability to influence the opposition, but its limited leverage on its loyal representatives of various Syrian ethnic groups and political parties. The most pro-Russian Syrians gathered in Sochi, but Alexander Lavrentiev could not win them over. This reality has once again revealed the difficulties that Moscow is experiencing, when it is necessary to achieve results by non-military means.

In Search of Allies

As lights switched off at the Sochi Congress, Moscow is currently focusing its diplomatic efforts on working closer with countries, such as Iran, Turkey and Saudi Arabia, that have a clout on the Syrian ground. Thus, during Salman’s trip to Moscow in October 2017, Russia confirmed that the Kingdom had the right to create a united opposition group to represent the anti-Assad forces at the next Geneva meeting. By late November, the meeting took place in Riyadh; whereas the Kremlin intensified its consultations with Tehran and Ankara about the upcoming Afrin Operation, and the future of the de-escalations zones.

Moscow also decided to allay Iranian and Turkish concerns about Moscow’s commitment to its partners’ obligations, inclosing Putin’s meeting with Trump, frequent meetings between Russian and Israeli officials as well as Russia’s silence vis-a-vis the Iraqi Kurdistan’s independence referendum, which increased certain concerns in Tehran as an indication that Russia opted for abandoning Iran in Syria. For this reason, Lavrov made his statement on the legitimacy of Iran’s military presence in Syria sending a clear signal to Tel Aviv that the Kremlin’s cooperation with Iran is no less important than with Israel.

Russia is far from having full control of the political process in Syria. As they sound promising on paper, Russian initiatives are not always successfully implemented in reality. For instance, the trilateral meeting of Russian, Iranian and Syrian presidents on November 22, 2017, was supposed to help the three countries dispel the existing tensions existing, and to work out a joint stance on the future of the political process. Nevertheless, Moscow has not been able to achieve these objectives. Despite its significant role in the Syrian negotiating process, Moscow’s resources and capabilities are clearly not enough to sustain progress. In turn, neither Iran nor Turkey are ready to play a secondary role in the negotiation process, which was evident in the recent high-level talks. The current situation affirms that any stakeholder(s) who will seek to shape the political process of the Syrian conflict settlement, they will face vary serious challenges and may not be able to overcome them in the long term.

ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ

Leonid M. Issaev is Associate Professor at the Department for Political Science at the National Research University Higher School of Economics, and Deputy Chair of the Laboratory for Sociopolitical Destabilization Risk Monitoring in Moscow.