As American psychologist, Abraham Maslow, wrote in "Toward a Psychology of Being" book in 1962,"if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail. Businessman-turned-president Donald Trump perceives the upsurge of Dow Jones, in numbers above 26600 points, as one of the most significant highlights, if not the most successful story of his presidency. He has often praised him for the 84 high closes of the stock market and their impact on 401(k)s, retirement, pension, and college-savings accounts, before the so-called "Trump bump" turned into a "Trump slump" after Dow Jones lost 1175 points about 4.6 percent on February 5. In his revealing op-ed "Has Trumphoria finally hit a wall?", Economics Nobel laureate Paul Krugman argues that the stock market is not the economy. This is a reminder for Trump and his supporters whether the high closes of the stock market trickle down to other sectors of the economy. It is also a wake-up call for Americans to refrain from maintaining high hopes of future economic growth and unemployment rate. As Krugman predicts, “at the very least America is heading for a downshift in its growth rate; the available evidence suggests that growth over the next decade will be something like 1.5 percent a year, not the 3 percent Donald Trump and his minions keep promising.”

The debate continues about any possible correlation between a ‘Trump factor’, the Obama legacy, and the upsurge of major indexes. A new Quinnipiac University poll has shown 48 percent of Americans credit Trump for the country's economic state, while 41 percent attribute it to the lingering impact of Obama's time in the White House. In the following article, Dr. James K. Galbraith of the University of Texas at Austin and author of “The End of Normal” book, among other publications, contextualizes the past year’s upsurge in the stock market, Trump’s keen push for a tax reform, and the impact of the U.S. Federal Reserve’s policies after the replacement of Janet Yellen by Jerome Powell. He also proposes two main predictions about the U.S. economic performance in 2018 and beyond.

Still not a Withdrawal

The Scarce was the ink dry on the tax cuts – crafted to boost economic growth by adding to corporate earnings – and hardly had President Trump used his State of the Union to take credit for a record stock market boom, than did matters suddenly change. As poet Archibald MacLeish once wrote,

Quite unexpectedly as Vasserot

The armless ambidextrian was lighting

A match between his great and second toe

And Ralph the Lion was engaged in biting

The neck of Madame Sossman while the drum

Pointed, and Teeny was about to cough

In waltz-time swinging Jocko by the thumb —

Quite unexpectedly the top blew off.

Within a week, the stock market was down by four percent – a thousand points on the Dow – and The New York Times was reporting that the economy look “shaky.”

The stated economic policy objective of the Trump administration has been to raise the rate of economic growth on a sustained basis, from the 2 percent or so characteristic of the post-crisis expansion to at least 3 percent and if possible beyond. The goal is not, on its face, unrealistic. The economy averaged over 3 percent real growth in 2005-2006 and over 4 percent real growth in 1997-2000; it was growing at near 3 percent in the second half of 2017. Before the stock dive, the question was how such rates might be sustained. Now the question has become: can they be sustained at all?

The net tax reductions are on the order of 0.9 percent of GDP annually in the first four years. How this will translate into spending depends on how much of the additional private income is spent in a given year, and on the fiscal multiplier to be applied to that spending. In a piece for Project Syndicatein January, I offered the guess that the figures might be 0.6 and 1.5 – generous guesses. In that case the tax cut would have added nearly a percent to the GDP growth rate initially, although offsetting cuts in spending, such as automatic reductions in Medicare set to be triggered by the tax-act changes, would counteract some of that. So would have cuts in Social Security – a topic that the President did not mention in his speech. Barring deep offsets, on the basis of the fiscal effect, the tax cut could easily push a 2-to-2.5 percent growth rate into the 3 percent range for a year or so, although the effect would be one-time only; after the initial climb to a higher GDP, there is no further impact on the growth rate. The question then becomes: will an underlying growth rate of even two percent be sustained?

The Story Behind Numbers

To understand what happens next, it would be helpful to review what has happened since the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-2009 and where things stand. After a very deep slump marked by heavy retrenchment in the financial and household sectors, a sharp reduction in labor force participation rates and a collapse of construction, recovery began thanks in large part to automatic stabilizers supporting private incomes and to the American Recovery and Reconstruction Act, which poured federal dollars into public investment. Net immigration fell to near-zero, and over time people adjusted to not-working, including via early retirements and disability insurance. Eventually the growth of consumer spending resumed, fueled in part by consumer, student and automobile debt.

Business investment and particularly construction never fully recovered, remaining as a share of GDP well below pre-crisis levels. One result was that the recovery remained slow, but on the other hand it continued for longer, without interruption from the inventory cycle, than was characteristic of past expansions. A significant exception came in energy, where the innovation of fracking produced a glut of oil and natural gas, lowering the market price of natural gas in North America and favoring the recovery of energy-intensive manufacturing, compared to Europe, as well as of household consumption. Meanwhile monetary policy supported liquidity by buying up financial assets, and the resulting liquidity, having no real outlet, poured into the stock market. Finally as the European crisis took far longer to resolve, the dollar remained a safe haven and the greenback remained strong, until European growth resumed in 2017, global oil prices recovered and the dollar declined.

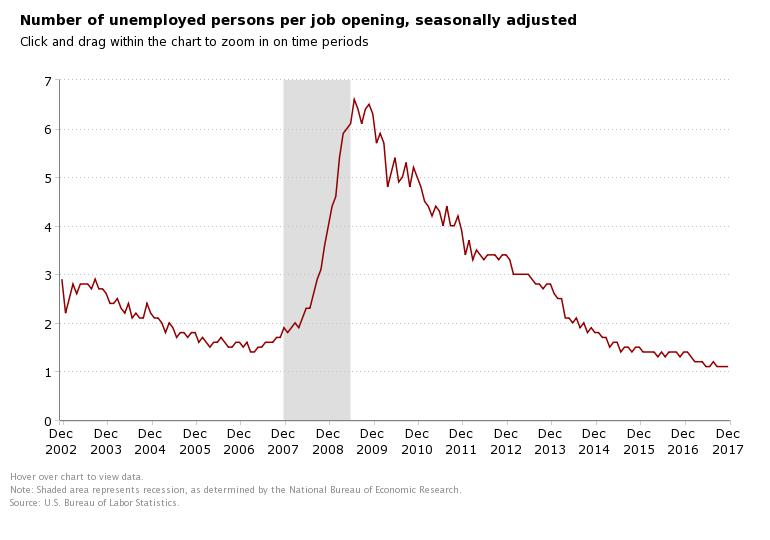

|

| Unemployment rates in the United States 2002 2017 [US Bureau of Labor Statistics] |

In 2016 and 2017, after long stagnation, reports held that even wages were finally beginning to rise. This is often read as a signal that the economy may be “overheating;” with businesses unable to find qualified workers, forced to bit up wage rates, and then to pass along the increased costs to consumers in higher prices. But at current – still low – levels of labor force participation and net immigration, along with free trade with much of the low-wage world, this explanation is not obviously correct. It is worth bearing in mind that the Bureau of Labor Statistics surveys firms on their payrolls and households on their earnings, but it does not have records of hourly wage rates associated with particular jobs – for the perfectly defensible reason that “job” is not a stable observable; firms change job descriptions all the time.

So when the newspapers report that “wages are rising” they typically mean that the weekly earnings of households are going up, and this is typically associated more with increased hours worked than with a higher hourly wage rate. Increased hours may bring overtime compensation, raising the average hourly wage without raising the underlying rate. They may come from a second job or a second or third earner within the household, or even from marriages that combine two earners or eliminate a non-earning household from the data. There is no reason to regard any of this as a sign of “overheating.”

Indeed, and on the contrary, late in an expansion employers may choose to increase hours, and pay overtime rather than add employees, because they anticipate (and fear) that economic activity may soon slow down. Using existing workers more intensively saves on training and turnover costs, which might easily be sunk, in short order, if firms expand their hiring in the face of an imminent downturn. We don't know exactly, but the increase in total employment, in these conditions, which continued to occur, may be coming from elsewhere: for instance enterprises that don't face major training costs. Good news on wages may be good news, or, maybe not.

|

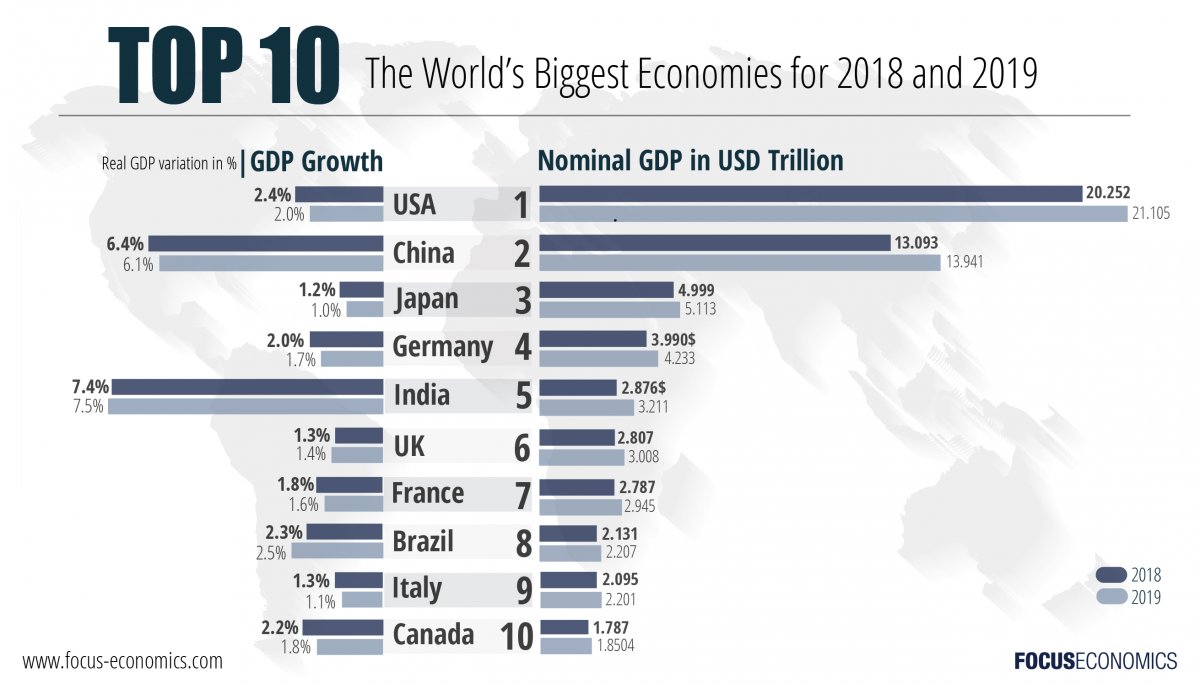

| The World's Biggest Economies for 2018 and 2019 [FocusEconomics] |

The Power of Deciding the Interest Rate

Apart from the sheer age of the expansion, there is a single most-likely reason why private businesses and the financial markets may fear that the expansion will soon end. And that, of course, is the policy of the Federal Reserve. The Federal Reserve reduced the short-term interest rate that it controls to near zero in the wake of the 9/11 emergency, and to zero in the calamity of 2008, where it stayed for five years. With expansion underway, the Federal Reserve has been signaling a desire to return to what it considers to be “normal” short-term interest rates – say a federal funds rate in the range of three percent. For a year, rates have been slowly rising, and it would signal a change in policy not to raise rates further. Since it is harder to change policy than to continue on any designated path, the reasonable expectation is that rate increases will keep coming.

The difficulty is that after a very long period of essentially free federal funds – and of quantitative easing on top of that – the long-term end of the interest-rate spectrum has adjusted to the expectation of low interest rates. And so interest-rate increases at the habitual 25 basis points per decision materially flatten the yield curve – bringing ever closer the moment when short rates rise above long rates, and (until long rates adjust upward) the financial markets collapse to the short end of the spectrum. This brings equities down and is, typically and for good reason, a harbinger of recession. That Federal Reserve moves toward tighter policy and higher interest rates have never ended in the fabled “soft landing” is not accidental. It is a feature of how the system works.

There are circumstances when increasing interest rates can set off a long-term business boom, by pushing the banking sector out of safe instruments and back into commercial and industrial loans. This happened in February 1994, the true starting point of the expansion that led, ultimately, to the information-technology bubble. But that was a moment when the technology revolution loomed, and banks needed a push to move them from reliance on a steep yield curve. Today the technological revolution is well-established and the yield curve is flat. The 1994 pattern seems unlikely to repeat.

More likely, if the Federal Reserve continues to raise interest rates – and even more so if it picks up the pace – the dollar will stop falling, and perhaps again start to rise. Imports of capital equipment will become even more attractive, substituting against domestic capital goods to the detriment of growth. A funding crisis in the rest of the world (hinted at by some analysts) would produce yet another a flight to quality and increase these effects. A financial crisis, exposing the weak position of some of the world's largest banks, would likely end growth altogether, and not merely in the US.

Against the powerful headwinds of expectation and interest rates, growth optimists point to the effect of improved corporate cash flow, and the incentive to repatriate earnings now held overseas, on private business investment. And indeed, there have been reports (from Apple and other companies) of big business taking advantage of the repatriation provisions to accelerate – at least modestly – their investment plans.

But of what does most business investment consist? These days new electronic machinery is relatively cheap; in many service sectors one can, in the limit, replace a check-out clerk or a waiter for the price of a couple of computers or a fistful of tablets. Further, electronic retail distribution networks economize drastically on commercial space. Because new machinery is physically compact, and because it displaces office labor, business structures are less necessary – than for instance in the automotive age or the golden age of insurance and banking. Because much equipment is now imported, a dollar's investment is offset by a dollar of imports, the effect on US GDP is (in that case) nil, and the multiplier is felt in the country that produces the capital goods. Partly for these reasons, business investment spending is low as a share of GDP. And the burden of sustaining growth has shifted toward consumption – which is why growth rates since the crisis have been both lower and more stable than they were before.

What is Beyond Numbers?

In the real world, businesses invest for two reasons: to expand production and to cut costs. The first reason requires confidence in the future growth of sales. The tax bill will boost sales initially – there will be a fiscal effect, as discussed above. But many provisions in the law will reduce middle class purchasing power and upper-middle class home values and economic security, and the ability of state and local governments to maintain tax effort and public services. These factors will undermine the consumer debt markets – perhaps by enough to offset the effect of increased incomes on spending. Meanwhile the vast gains to the very rich won't affect their spending at all; the spending of the very rich is not constrained by their incomes.

It is possible that there will be a boost to commercial building. Some firms may decide that they must expand or lose market share, even though there is ample capacity in existing commercial buildings. There is the further thought that favorable tax treatment on structures will enable large companies to muscle in on the remaining market share of small retailers, restaurants and other service providers. In that event, we will a see a bubble, followed by a bust, in commercial structures.

How likely is this? The architects of the tax cut are surely aware that the last two economic expansions – in the late 1990s and in the mid-2000s – were both bubbles generated by co-respective behavior on the part of technology investors in the first instance and of speculators in corrupt mortgages in the second. There is the phenomenon of a “melt-up” – advanced by Jeremy Grantham; if it occurs it may sustain growth for another year or so. A new bubble would reap short-term applause and the political benefits. But, the crack in the stock market makes this scenario less likely.

That leaves two possibilities. One is that there will be a surge in after-tax corporate cash flow, in which case the money will be channeled to executive compensation, stock buy-backs and (perhaps especially) into real estate, notably the conversion of the American housing stock from no-longer-tax-advantaged ownership to rentals. There seems little doubt that the prospect of a large tax cut and future buy-backs helped to fuel the stock market in Trump's first year. But with a flurry of buy-back announcements as the tax bill moved toward the President's desk, it may be that this particular moment is now over.

|

| [Reuters] |

The other possibility is that with the tax cuts now in hand, and the stock market going down, corporations will curtail their investments. They may figure on a general slowdown (following the initial effect) in consumption, and state/local government cutbacks under pressure from constituents who can no longer deduct state and local income taxes – among other things pushing states and localities to raise local sales taxes to compensate. In this case, the underlying growth rate of 2 percent or so may not be sustained for very long, and the economic picture will look very different in a year, or possibly two years, than it does today. While for the moment the Republican Party is enjoying a modest recovery from dangerously adverse polls, it is hard to see how that recovery can continue if bad news from the markets eventually translates into bad news for the economy as well.

The break in the stock market does not, yet, tell us which of these possibilities is most likely. But it does weight the chances toward this last one. So far as Trump and his tax cut are concerned, perhaps the last word belongs to Archibald MacLeish:

And there, there overhead, there, there, hung over

Those thousands of white faces, those dazed eyes,

There in the starless dark, the poise, the hover,

There with vast wings across the canceled skies,

There in the sudden blackness, the black pall

Of nothing, nothing, nothing — nothing at all.