Despite some obvious differences, all Arab Gulf States share the same two fundamental objectives in the contemporary era – socio-economic development at home and the consolidation of security and defense on the regional level. Since the ill-fated invasion and occupation of Kuwait by Saddam Hussein’s Iraq in 1990, the strategic doctrines of all the Arab Gulf States have been shaped by a belief that this second goal is best served by deep and wide-ranging bilateral relations with the United States (U.S.), the dominant international security actor since the end of the Cold War. This embrace of U.S. protection as a key pillar of security and defense has also led them all to neglect, to varying degrees, the building of an autonomous regional security capability and the development of extensive security relations with external actors other than the United States. Unfolding events during the presidency of Barak Obama between 2009 and 2017 significantly eroded Arab Gulf confidence in Washington’s role as the main security provider for the Gulf over the longer-term. This has led local actors to search for potential alternative security structures and partners. This article examines the implications of this shift for international actors in the Gulf and for the regional balance of power since the end of the Obama era and the accession of Donald J. Trump to the US presidency.

Losing Faith in the US Security Guarantee: The Obama Era

In the first term of the Obama presidency between 2009 and 2013, relations between Washington and the Gulf capitals, though already under some strain were also, for the most part, still in good working order. American diplomats stationed in the region reported home on the Arab Gulf’s rising power and influence in the wider Arab world and the golden opportunity that this provided for Washington. The US National Security Strategy issued by President Obama in May 2010 acknowledged this explicitly. It described American strategic ties with the member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) as among America’s ‘key security relationships’ and promised to ‘work together more effectively’ in the future.(1)

In the heady days of the Arab ‘Spring’ in early 2011, Saudi leaders lobbied their U.S. counterparts to fully and openly back Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak. Instead, the Obama administration offered cautious support for Egyptian protesters and then called for Mubarak, a long time American partner, to give up power after only days of popular protests. According to Saudi officials, King Abdullah’s faith in the US completely ‘evaporated’ following the debacle in Egypt. (2)

Washington’s subsequent public rebuke of Bahrain’s royals and the calls by U.S. officials for the ruling family to ‘address the legitimate grievances’ of the protestors and undertake a ‘process of meaningful reform’ also appalled Saudi leaders. In response, Riyadh undermined American efforts to mediate a compromise agreement between the Bahraini leadership and local protestors.

Iranian leaders capitalized on these tensions. Speaking soon after Mubarak’s demise, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khameini noted that when Washington realized Mubarak could not be saved ‘they threw him away.’ This, he added, should serve as a ‘lesson’ for other local leaders who are dependent on the US, ‘When they are no longer useful, it will throw them away just like a piece of old cloth and will ignore them’.(3) Such rhetoric alarmed Gulf leaders preoccupied with the multifaceted challenge they faced from Iran by this time. The rivalry between the Sunni Arab monarchies of the Gulf and Shia-Iran long predated the 1979 revolution and in the modern era can be traced back to the heyday of the Shah. It reflects a common strand of thinking in the Arab Gulf, where suspicions run deep that the revolutionary leaders in Tehran, like the pro-Western Shah they replaced, are striving to build a “Greater Iran” that can dominate the entire Persian Gulf and Arabian Peninsula and project power across the wider Middle East and Muslim world.

During the presidency of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad between 2005 and 2013, traditional Gulf fears increasingly revolved around the profound threat to the regional security balance posed by a nuclear Iran. In order to prevent this from happening the Gulf States predictably looked to the US to counterbalance Iranian ambitions. Obama’s top foreign policy officials repeatedly attempted to reassure Gulf leaders that they could rely on American support in their quest for security. In the summer of 2009, U.S. Secretary of State Hilary Clinton announced that the US would consider extending a defense umbrella over the region to prevent Iran from intimidating and dominating its neighbors. John Kerry, Clinton’s successor as Secretary of State, made similar commitments to expand military ties with the Arab Gulf and oversaw the establishment in 2012 of the US-GCC Strategic Cooperation Forum, which was tasked with drawing up plans to prevent an Iranian airborne attack on GCC territory. Kerry followed this step up with a commitment to expand regional security through cooperation in several key areas including intelligence sharing, the training of Special Forces, maritime security cooperation and the protection of critical infrastructure.

Important as such moves were, they did not serve to overcome or neutralize the Arab Gulf’s growing disillusionment with Washington in the wake of the Arab ‘Spring’. Despite the promises made by Clinton and Kerry, statements emanating from Obama’s Secretary of Defense Robert Gates seemed to suggest that the administration was intent on reducing its commitment to the region. So too did the shifting focus in U.S. military planning toward the Asia-Pacific theater. At the beginning of 2012, the U.S. Defense Strategic Review, announced by President Obama seemed to confirm this shift in priorities.

|

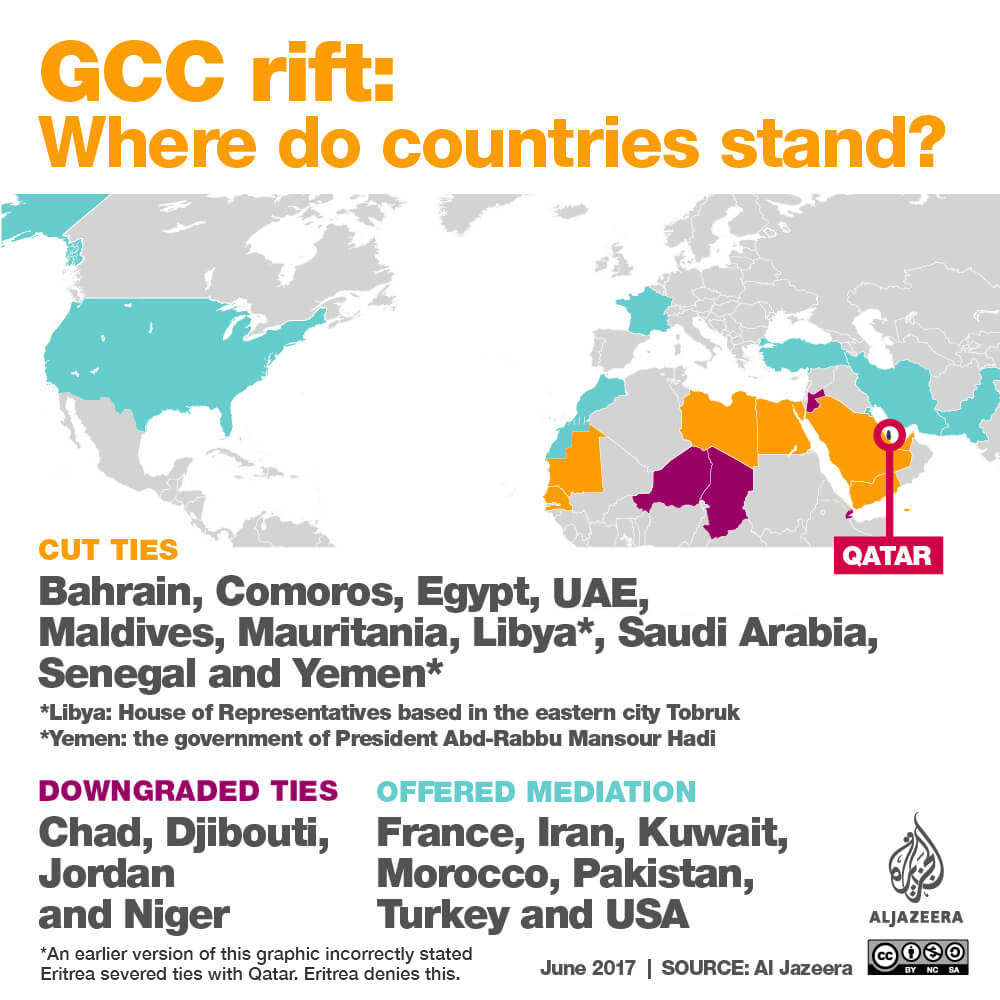

| GCC Rift [Aljazeera] |

The Arab Gulf States had been excluded from the negotiations between Iran and the members of the P5 1 (the five permanent members of the UN Security Council plus Germany) over Iran’s nuclear program. When a final agreement was signed in July 2015, the Gulf States cautiously and resignedly endorsed it. Yet Gulf leaders still worried that Iran might renege on its commitment or that even if the agreement held it would leave Iran unchecked and free to promote its hegemonic intentions across the region. There were also growing concerns that the nuclear deal would serve as the basis for “grand bargain” between Washington and Tehran, and that the GCC would be the first and biggest casualty of any American-Iranian reconciliation.

This growing perception of the United States as an unreliable and fatigued ally, in retreat and unwilling to stand up to Iran and its proxies in the region gained further credibility as the situation in Syria deteriorated. This was compounded by the refusal of the Obama administration (like all its predecessors) to turn its de facto security commitment to the Arab Gulf into a formal treaty obligation.

By the time that the Emirs of Kuwait and Qatar and the high-ranking figures from the other four GCC states arrived at the Camp David presidential retreat for a summit with President Obama in May 2015, it seemed to many decision-makers in the Arab Gulf that the Obama administration was unwilling to act, or even incapable of acting, in defense of Gulf security and stability as regional crises spiraled out of control. In the run-up to the Camp David meeting, the UAE’s influential ambassador in Washington, Yousef al-Otaiba, summed up this growing lack of trust: ‘We definitely want a stronger relationship’, he explained before adding, ‘we have survived with a gentleman’s agreement [with the US on security]. I think today, we needed something in writing’.(4) That four Gulf rulers stayed away from the summit, choosing instead to send lower ranking officials to meet the US president, was also widely viewed at the time as evidence of growing Gulf Arab disillusionment with their most important strategic partner.

Addressing the Shrinking Power Differential: The Trump Era

Donald J. Trump became U.S. president at a time when the power differential between the United States, Russia and other international actors was shrinking. This process has been most evident in the Middle East where local actors are increasingly unsure whether the United States retains the political will, legitimacy and the requisite power to provide institutional leadership and shape outcomes in the regional system. During the first year of the Trump presidency as well as the final ones of the Obama era, this concern has raised the possibility that the U.S. might withdraw from the region leaving a security vacuum that plays into the hands of Iran. This possibility has pushed Gulf leaders to search for alternative security partners and to pursue new alliances.

One can see this political climate clearly in the way emerging actors like India and China have expanded defense and security ties with the Arab Gulf both before and since the launch of the blockade of Qatar in June 2017. The Gulf is one of India’s top trade partners and the region is viewed more and more as part of India’s economic hinterland. The Arab Gulf is also a key component of India’s major strategic initiative, the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium that was launched in 2007. During recent visits, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has made a firm commitment to strengthen security and defense, as well as economic relations, with the region and has signed several bilateral defense and security agreements with individual GCC states.

In 2010, China established the China-GCC Strategic Dialogue and in the years since its interactions with Arab Gulf partners have moved beyond extensive cooperation on trade and energy into the realms of security and defense. As President Xi Jinping explained during a visit to Kuwait in 2014, China ‘stands ready to work with countries in the region to promote political solutions of regional issues and safeguard local peace and stability’.(5)

Yet neither India nor China, which has become a viable hard power challenger to the U.S. in Asia, have the political will or the military capabilities to take advantage of Washington’s perceived abdication of its traditional leadership role in the Gulf. Certainly, neither has demonstrated a real commitment to draw regional states away from their reliance on the U.S. security guarantee and even less of a desire to play the role of strategic balancer in the Gulf, a region that they both still consider an American sphere of influence.

The two ‘big’ European security and defense actors – France and the United Kingdom – pro-actively pursued major security and defense agreements across the Arab Gulf throughout the Obama era. In 2009, for example, France opened a military base in Abu Dhabi, its first new foreign military base in 50 years, and its first establishment ever outside French or African territory. However in the post-Arab ‘Spring’ era, they both looked to capitalize on growing disillusionment in the Gulf with U.S. policies to increase their security roles and arms sales. For example, in 2014, the UK announced an agreement with Bahrain to establish a permanent naval base on the island, and also signed a major security cooperation agreement with Qatar.

In response to the opportunities created by the Trump presidency and the Brexit vote, both France and the UK have ramped up efforts to increase their security and defense roles in the Arab Gulf. In doing so, they have taken particular advantage of the long-time desire of Gulf policymakers to diversify sources of arms imports away from the US. In 2017, Britain signed a deal to sell more Qatar 24 Typhoon Fighter planes for US $3 billion. In the same year, France signed a massive US $14 billion deal with Qatar for jets, armored vehicles, advanced weapons systems and civilian infrastructure. This agreement came just two years after Qatar purchased 24 Rafale fighter jets from the French manufacture Dassault Aviation for U.S. $7.1 billion. Yet, despite such successes, which underscore the importance of both countries to the defense acquisition strategies of regional players, neither France nor the UK have the military capacity, resources, or political will to replace the United States as the Gulf’s main provider of external security and defense.

|

| Global arms deals [SIPRI] [Al Jazeera] |

In the decade following the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia energy companies focused overwhelmingly on domestic economic and political reconstruction and on its relations with Eastern Europe, the North Caucasus, and the former Soviet republics of Central Asia. When Moscow did engage with the Middle East, it was to mend fences with former Cold War foes like Egypt, Jordan, and the Arab Gulf states; and to participate in multilateral efforts to bring peace to Israel and the Palestinians. At no point between 1991 and the early 2000s did Russia attempt to challenge U.S. dominance of the region or even serve as balancer to the US for regional actors suspicious of Washington’s intentions.

Under Vladimir Putin, who has just secured a forth six-year term in power in March 2018, an increasingly pro-active and assertive Russia took advantage of the instability, insecurity, and disorder that followed the ill-fated US invasion of Iraq in 2003 to re-enter the Middle East. Since then Russia has consistently attempted to challenge and undermine America in the region as part of its strategy of re-establishing its Cold War standing and influence on the global stage.

Russia’s Middle East policy has never simply been a function of its anti-Western agenda or competition with the United States. It is also an expression of Russian norms and legitimate interests in its “near abroad.” Paradoxically, Russia’s strategic relationship with Iran, and its decision to prop up the Assad regime in Syria alongside its Iranian ally, have been, to some extent, a function of its renewed competition with the United States.

For example, Russia’s involvement in Syria during that country’s civil has not simply been limited to providing the diplomatic, material, and military backing required by the Assad regime to survive. It has also been about using the crisis in Syria to diminish America’s legitimacy, credibility, and leadership in international affairs; and to herald the return of a multipolar world after two decades of U.S. dominance. As one of many similar headlines in the media put it in 2016, “Russia’s grip on Syria tightens as brittle ceasefire deal leaves US out in the cold.”(6)

The evolving Iranian-Russian axis and Moscow’s central role in saving the Assad regime in Syria have antagonized much of the Sunni world, and even led to some religious leaders declaring a “holy war” against the Putin government. But in the absence of strong U.S. leadership under Obama and Trump, and in response to pro-active and wide-ranging Russian efforts to build relations with many of America’s key regional allies –notably Turkey, Israel, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar –there is a rising consensus across the region that Putin’s Russia is in a much better position than Washington to moderate Iranian behavior or find a settlement in Syria. More generally, Russia is now viewed as an important regional player whose interests must increasingly be taken into account.

The Gulf Crisis: Return of the U.S. Dominance?

Gulf leaders approached Trump’s presidential election victory with an open mind. He was unpredictable, and lacked the foreign policy experience of his opponent Hilary Clinton. During the election campaign, he had also publicly criticized Saudi Arabia and other Gulf allies for not paying their fair share for US security protection. On the other hand, he also appeared to be a pragmatic figure committed to revitalizing the US role on the global stage and it was hoped that he would move quickly after taking office to reassure Gulf allies over the US commitment to their region in a way that they believed Obama had refused to do.(7)

In March 2017, Saudi power player Mohamed Bin Salman became the first Arab leader to be welcomed at the Trump White House. Two months later, Riyadh was the destination of President Trump’s first overseas trip. While in the Saudi capital Trump participated in an Arab-American-Islamic Summit, attended by senior figures from 55 other nations, and hosted by the Saudis to demonstrate their leadership of the Muslim world. Soon after Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain – three of Qatar’s closest economic and security partners – as well as Egypt, and several smaller Arab and Muslim states like Mauritania, broke off or downgraded diplomatic relations with Qatar and initiated a quasi-embargo by land, sea, and air.

This move against Qatar in June 2017 was part of a wider Saudi/UAE attempt to overturn the traditional security architecture in the region. It began in the wake of the Arab ‘Spring’ and before Trump became president. But, his election offered the opportunity to sideline the defensive security model previously pursued by Washington’s Arab Gulf allies and replace it with a more offensive security strategy – in Yemen, and against Iran and subsequently Qatar.

During the first year of the Trump presidency, it seemed that the champions of this new approach in Abu Dhabi and Riyadh had a receptive audience in Washington. Yet President Trump’s seeming support for blockade last summer appeared to abdicate responsibility for regional security to a new leadership in Saudi Arabia, backed up by the UAE, that sough to destabilize the most stable part of the Arab world in the pursuit of their own interests. This shift added to the erosion of American legitimacy and credibility and provided a further opportunity for other actors, above all Russia, to once again challenge America’s previously pre-eminent position.

From the start of the Qatar blockade in the summer of 2017, U.S. Secretary of Defense Mattis and, prior to his dismissal in March 2018, Secretary of State Tillerson, played a central role in searching for a compromise solution to this breakdown of relations between Washington’s Gulf allies. This was evident during the first session of the US-Qatar Strategic Dialogue in Washington in January 2018. At that meeting and subsequently, both men called attention to the blockade’s economic and human impact; the damage it was doing to the GCC as a regional organization, not to mention its negative effect on the War on Terror and the containment of Iran. Even Trump has moderated his position on the crisis in recent months by calling for a return to the status quo ante that existed before the blockade began and by offering to mediate a solution with the parties in Washington or at Camp David.

|

| Qatar's new plans [State of Qatar] [Al Jazeera] |

Some commentators have described this U.S. shift as transactional and evidence only of the fickleness of current administration. The recent firing of Secretary Tillerson may prove this assessment correct. It is also quite possible that President Trump will be influenced to change course during his meeting with Saudi Crown Prince Mohamed Bin Salman, who decided to go on a prolonged trip to Washington and other parts of the United States. Nevertheless, the evolving U.S. position on the crisis in recent times has so far served as a major blow to the credibility of the vision set out by Saudi and the UAE for the region’s future security architecture. In particular, the shifting U.S. attitudes on the crisis undermine the claim by Saudi and UAE leaders that the best way forward for regional stability, and American interests, is the pro-active militarization of conflicts and the break-up of existing regional structures under their leadership. Qatar US strategic dialogue [Video]

It is no longer taken for granted that ‘American leadership is the one constant in an uncertain world’ or that the U.S. is and remains the one indispensable nation’ as President Obama argued in two different speeches in 2014. Time and again during the Obama and Trump presidencies, the United States has been unable to provide local actors with the security, stability, and order they expect from the dominant security actor. It has also failed to demonstrate power, if we define power as the ability to influence outcomes and to provide institutional leadership.

However, the response by top U.S. administration officials to the current Gulf crisis in recent months has provided an important opportunity for the Trump presidency to demonstrate that the United States, rather than would-be-challengers, remains the dominant external actor in the region and the only one capable of serving as an effective mediator between Qatar and its neighbors. This eventuality does not mean that the U.S. is able to impose its will on local actors; but it does underscore that there is no structural change to the regional strategic power balance, and that the United States, despite its much-reduced position, continues to be the ‘powerful outsider’ at the center of this vital region.

|

| Miller’s book |

(1) US National Security Strategy, 27 May 2010, Chapter 3, ‘Advancing our Interests’, p. 45, http://nssarchive.us/national-security-strategy-2010/

(2) Helene Cooper and Mark Landler, ‘Interests of Iran and Saudi Arabia collide, with the US in the Middle’ The New York Times, 17 Mar 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/18/world/18diplomacy.html

(3) Ali Alfoneh, ‘Mixed Response in Iran’, Middle East Quarterly, Summer 2011, p.39, http://www.meforum.org/3006/mixed-response-in-iran

(4) Deb Reichmann, ‘Gulf nation leaders look to Obama for reassurance of fears over Iran’, Associated Press, Associated Press, 10 May 2015, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/gulf-nation-leaders-look-obama-reassurance-fears-iran

(5) ‘Xi meets Kuwait prime minister’, China Daily, 4 June 2014, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2014-06/04/content_17563183.htm

(6) Alec Luhn, Martin Chulov and Emma Graham-Harrison, ‘Russia’s grip on Syria tightens as brittle ceasefire deal leaves US out in the cold,’ The Guardian, 13 February 2016 , https://www.theguardian.com/theobserver/2016/feb/14/russia-syria--munich-peace-conference-ceasefire-vladimir-putin-bashar-assad-isis

(7) In a series of foreign policy interviews published in April 2016 in The Atlantic magazine, Obama was reported as saying that Saudi Arabia should ‘share’ the Middle East with Iran by finding some form of ‘cold peace.’ Jeffrey Goldberg, ‘The Obama Doctrine,’ The Atlantic, April 2016. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/04/the-obama-doctrine/471525/