In the wake of the killing of more 300 Muslim worshippers by allegedly Jihadist militants during al-Rawdah massacre in November 2017, President Sisi launched a new military campaign, “Comprehensive Operation-Sinai 2018”, with the aim of putting an end to terrorism and restoring security within three months in turbulent Egypt. The military operation, which precedes the presidential election of March 26-28, 2018, has pursued growing repression of the opposition and militarization of institutions in the country. Despite the media fanfare and pro-Sisi triumphalism, the Egyptian government needed a red herring and the construction of an ‘enemy’ to help engineer some ‘national unity’ among disgruntled Egyptians, with the aim of diverting public attention away from atrocities and structural reform failures.

Operation Sinai-2018 represents a new step in the militarization of the restive northern part of the Sinai Peninsula, where the State and the Army have reasserted their control under authoritarian policies based on brutal force and harsh methods against the local population. This paper analyses the reasons behind the military operation and examines the threats arising from the militarization policy in Sinai and the impact of authoritarian measures on domestic politics. It also probes into the emerging correlation between military measures and militaristic nationalism, and how new risks may arise during Sisi’s second presidential term.

Revenge Politics or an Election Tactic?

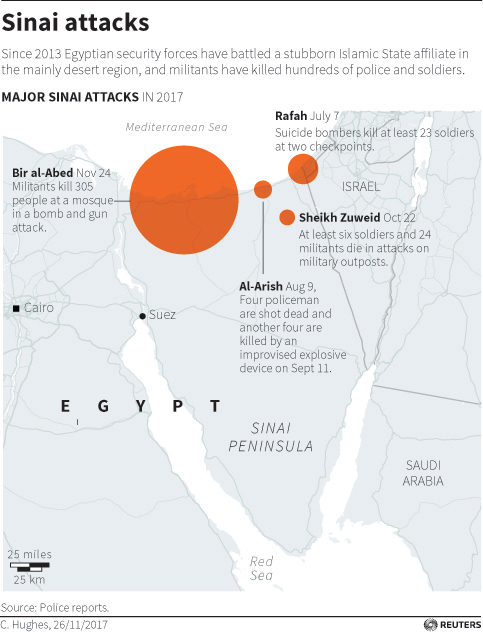

Col. Tamer Refai spokesman of the Egyptian Armed Forces (EAF) made the announcement of “Comprehensive-Operation Sinai 2018”, on state television February 9 , as a large-scale operation involving land, naval, and air forces, as well as police and border guards, against whom he deemed “terrorist and criminal elements or organizations” not only in the Sinai Peninsula, but also in other parts of the country, including the Nile and Delta Valley and the Western desert(1). This operation was a retaliation against the brutal assault on the al-Rawdah mosque in Bir al-Abed, a small village in northern Sinai November 24, 2017. The attack was the worst ever in Egypt’s history, killing over 300 worshippers, and was allegedly launched by members of Wilayat Sinai (WS), the Islamic State branch in Egypt.

To eradicate violent extremism, Egypt’s security forces deployed heavy weapons and military equipment ranging from howitzers to fighter jets, tanks, and attack helicopters in the Sinai, Suez Canal and Ismailia. The army also has a variety of extraordinary measures at its disposal, such as the evacuation of hospitals and schools, roadblocks and checkpoints, as well as the relocation of local inhabitants in southern Sinai and even in mainland Egypt.

According to several news agencies, the EAF and the police have focused their actions and strikes on areas near the Israeli-Gaza border, in the cities of Rafah, Sheikh Zuweid, and al-Arish, where the insurgent groups were most active(2). Meanwhile, Israel has built another defensive fence along its southern borders and Israeli intelligence services are unofficially cooperating with the EAF, as David Kirkpatrick noted in an article in The New York Times. This security threat became more concrete after the numerous rocket launchings from the Gaza Strip and the Egyptian border to Israel’s Negev region(3). Obviously, eradicating violent extremism and ensuring stability along its southern border remains a priority for Israel almost as much as combatting terror threats is for the Egyptian regime(4). Moreover, a second front in the military campaign has opened in the Western Desert near the Libyan border and in several governorates along the Nile and Delta Valley, where groups of terrorists could launch new attacks. Egyptian security forces have the specific tasks of defending and securing southern and western border areas.

This new operation involves strengthening of securitization policies in the most important Egyptian governorates (i.e. Cairo, Qaliubiya, Daqahliyah, Beheira, Menoufiya, Sharqiya, Asyut and Fayyum), where radicalised Muslim Brotherhood factions, such as Revolutionary Punishment (RP), Helwan Brigades, Liwa al-Thawra and the Hasm movement, are responsible for numerous attacks(5). As Maj. Gen. Samir Farag points out, the military campaign is a “pre-emptive strike against terrorist groups ahead of the election”(6).

Mobilization for Operation Sinai-2018

The timing of launching the new anti-terror operation in early 2018 has been suspicious and controversial. Sisi’s decision came amidst an unsettled debate over whether he has fulfilled several campaign promises he made during his presidential campaign in 2014. Egypt was experiencing terrorist attacks, rising political tensions and a deep economic crisis, whereas former Field-Marshal Sisi promised political stability, eradication of terrorism, and socio-economic prosperity for the 90-plus millions of Egyptians. Today, this scenario seems to be a distant prospect. Other reasons lie in the rising threats during the 2018 election campaign. According to different military intelligence reports, extremist groups were planning to carry out attacks across Egypt during the presidential elections, in order to erode citizens’ trust in the state’s ability to guarantee security in the country(7). Apparently, the main motivation for Sisi’s decision is more likely his desperate need to distract attention from the economic vulnerabilities and hardships facing the vast majority of Egyptians. In light of these reasons, he authorized a comprehensive military operation in an attempt to “save the country”, his reputation and credibility(8).

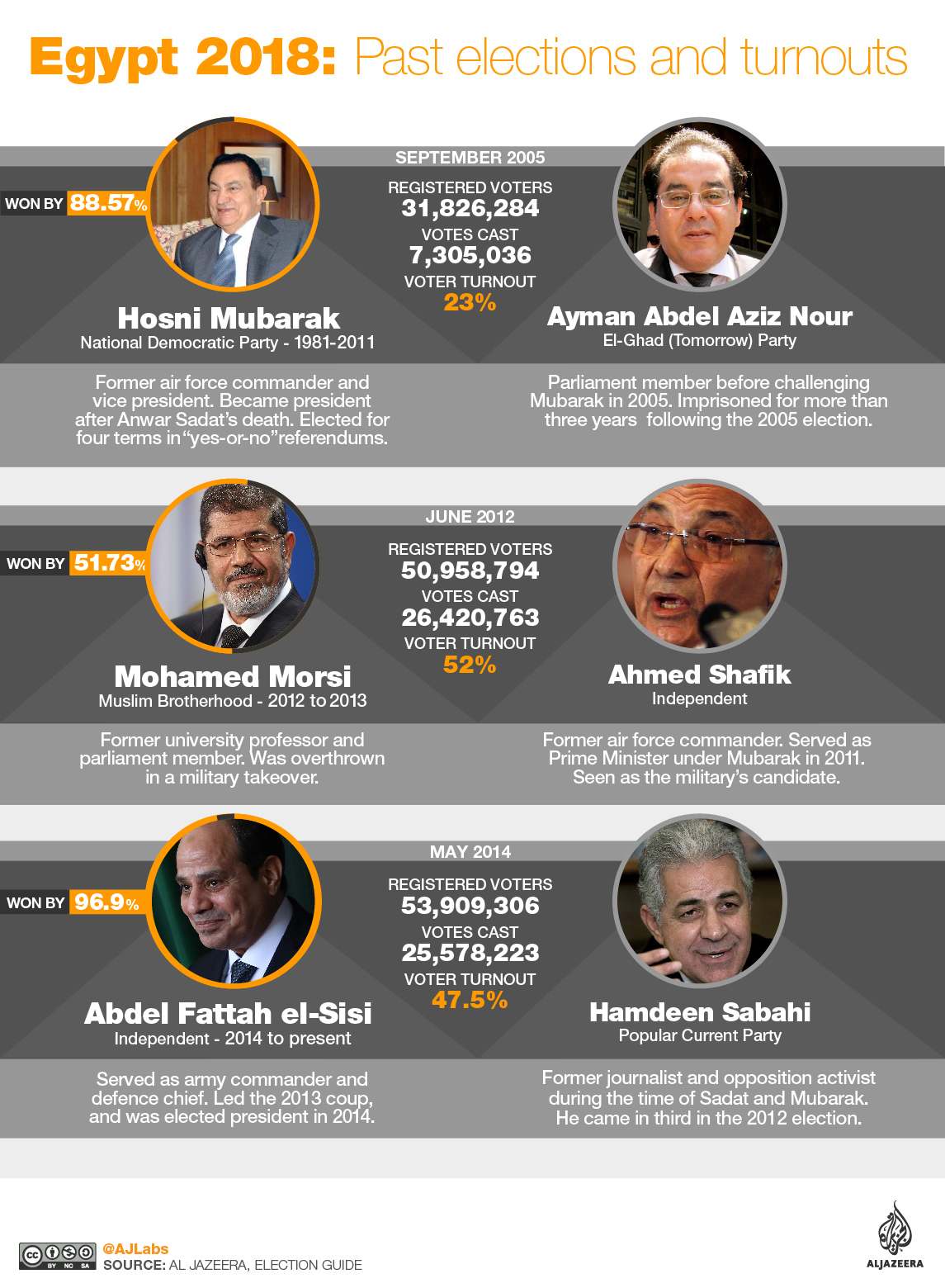

Nevertheless, a large contingent of Egyptian politics has strongly supported his decision to fight terrorism, such as the Civil Democratic Movement, which includes liberal political parties, and Hamdeen Sabahi former presidential candidate in 2014. No less enthusiastic have been the members of the Egyptian parliament, including Speaker Ali Abdel-Aal, who has guaranteed his personal support for the elimination of terrorism. Religious institutions, too, such as al-Azhar and the Coptic Orthodox Church, declared their support for Operation Sinai-2018. Large segments of Egyptians vowed to make more sacrifices for the eradication of extremism, arguing it is necessary to destroy this ‘social cancer’(9).

|

| [Reuters] |

Risks of the ‘Pragmatist’ Security Paradigm

After launching the new operation, the Egyptian Armed Forces announced that more than 100 ‘jihadists’ had been killed and hundreds were detained. Combined raids led by the police and military have made it possible to further reduce the operational capabilities of the militant groups in northern Sinai. Egyptian counterterrorism expert Brigadier General Khaled Okasha explained how “the army has consolidated its resources after months of piecemeal counterterrorism operations which were generally under-resourced. [In fact] [t]he inroads the operation has made in destroying the terrorists’ infrastructure has revealed how deeply terrorist groups had penetrated the area.”(10)

Three weeks after the start of Operation Sinai-2018, Egyptian media reported Mohamed Farid, Commander-in-Chief of the Egyptian army, made a request to President Sisi to extend military operations for more than three months. Farid explained that the reason was due to the difficult logistical, geographic, and security conditions that have challenged the deployment of Special Forces in the targeted areas. Although militant groups have weakened, they still can count on the support of locals, and continue to pose a serious threat for the EAF. According to several Egyptian analysts, the Army might be the target of potentially mega-terrorist attacks during the military campaign. This fear tends to confirm how the bloodshed, which started with the ousting of Mubarak in February 2011, still undermines the stability of whole country and any failure, or faux pas, in the “Sinai war on terror” could further weaken the status of Sisi. There have been some indicators that militant groups like WS, al-Qaida, and Hasm have not relinquished the idea of attacking certain minorities and civil-military symbols of power, which have created even more havoc in the domestic context(11).

Political violence and militarization have increased significantly in Egypt since July 2013, after the ousting of President Mohamed Morsi when an interim military-led government seized power. Since summer 2013, acts of terror have spread gradually from Sinai to the Egyptian mainland. These attacks and explosions have caused the death of nearly 3,500 soldiers and militants. Over 700 civilians, including members of Egypt’s minorities like Coptic Christians, Muslim Sufis, and foreign tourists, have been killed in various attacks, although unofficial numbers indicated the death toll was significantly higher(12). With the intensification of the militant group’s attacks, some jihadists and radical Bedouins personalized Morsi’s ouster as a pretext of legitimizing their ideological and political battles in the country and expanding their geographic influence from the Peninsula to the deep Egypt and immediate borders with southern Gaza and eastern Libya. The Cairo government seized the opportunity of reoccurring violence to expand its militarist policies from Sinai into the mainland under the banner of maximizing security in the country(13).

Local inhabitants of northern Sinai have accused the Egyptian security forces of shelling civilian areas and for being responsible for the extrajudicial killings. Furthermore, the military authorities have isolated al-Arish, Sheikh Zuweid, and Rafah from the rest of the country in order to stop the flow of militants, while investigating who support them. Consequently, the humanitarian crisis has deepened and local residents have suffered chronic shortages of food and medicine(14). The Egyptian Armed Forces have sought to justify this critical situation as a necessity for the ‘fight against terrorism’.

The open-ended use of hard power by the Egyptian authorities against entire populations in Sinai may push more individuals to sympathize with the militant groups, perceived as “defenders of the local population’s interests” against the alleged abuses of state(15). Moreover, these practices of power-politics can be counterproductive, since they tend to stimulate a trend of radicalization with the underpinnings of the culture of resilience in a fight for survival. They may trigger grave consequences for Egypt’s national security. The combination of anger and frustration towards Cairo, contestation of political opportunism as well as feeling of marginalization and victimhood may serve as important drivers of local radicalization processes(16).

Reproduction of ‘Saviour’ Sisi with Machiavellian Touches

As part of its militarized strategy, Egyptian authorities have invested heavily in disinformation, conspiracy theory, and populist narratives, while highlighting a zero-tolerance strategy towards political Islam as well as progressive movements. The governmental approach has vowed to fight and, possibly, eradicate violent Islamist extremism in the country under the banner of ‘security’ and ‘justice’. It simply perpetuates the very repressive 2013 policy that has enforced counterterrorism laws, banning protests, extending emergency rule, and expanding military court jurisdiction over civilian cases(17). The government institutionalized the National Council to Confront Terrorism and Extremism (NCCTE), pushed for the reform of Islamic education curricula with hole of curbing religious extremism. It has also cracked down on media in its pursuit of exerting control over virtually all forms of public expression and impeding criticism of the regime(18).

These old and new strategies have implied a deliberate move toward hyper-securitization and transformation of Egypt into a police state. However, they have failed in achieving their goals because the central authorities have ignored various structural problems, and opted for the politicization of any ‘real’ or ‘alleged’ security threat(19). The armed forces have justified their actions as ‘combatting security threats’, and used extraordinary powers to expand their influence in the judiciary, for all intents and purposes substituting for civil authorities and creating de facto a parallel legal system ruled by military institutions(20). The increase in repression has fostered not only a rise in militant violence, but also a heavily militarized and imprecise response that still fuels a steady penetration of radical Islamism in Egyptian society. As Steve Cook Middle East analyst at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) wrote recently, “Cairo’s single-minded pursuit of the Brotherhood – and of any Islamist group that bears the slightest resemblance to the Brotherhood – has become the guiding principle of Egypt’s foreign, as well as domestic, policy”(21). There is evident exploitation and manipulation of a nationalistic narrative tempered, by perceived terrorist threats, in shaping a propaganda machine with the simple aim of empowering Sisi and his personal inner circle, and constructing an image of a president to ‘talks tough and acts tough’.

|

| [AlJazeera] |

Politics of Restoration

The Egyptian Armed Forces maintains a pivotal role in the country as they stand as a social force, a bulwark against disorder, and an element of stability and prosperity. Since the Free Officers’ revolution led by Gamal Abdel Nasser, which overthrew the monarchy in 1952, they have also dominated politics and the economy, and positioned themselves as the state and “shepherds of the revolution”. With the exception of the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi to power (August 2012-July 2013), all of Egypt’s presidents and prime ministers have come from the army dominating the cabinet and senior governmental positions. Since the 1950s, the Egyptian army has been the strongest institution within the Egyptian polity, although in the 1990s, during the Mubarak era (1981-2011) the rise of a new wave of civilian powers (judiciary, business élites and national police) had substantially reduced the leading and uncontested role of the military institutions and promoted an oligarchic system(22). Consequently, the restoration of what is known in Political Science studies as “stratocracy” appeared as a logical consequence for the EAF and their historical significance in Egyptian dynamics. The role of the armed forces was not only restored, but the revolutionary events in 2011 and 2013 have strengthened their hold on the socio-economic transformations of the state, while remaining the prime source of political legitimacy for any Egyptian president and their own interests(23).

Behind the Shadow of ‘Rais’

With the help of the military institution, incumbent president Sisi has sought to restore and promote resurrection of the Nasser legacy in a double attempt to cultivate a nostalgic iconography of modern Egypt and to strengthen an abstract idea of Egyptian nationalism. His efforts to harness the myth of the “Golden Age” of Egypt (1950s-1960s) are instrumental in mobilizing support for his policies. In line with his predecessor Nasser, Sisi has stimulated a narrative based on a “new Egyptian dream” in which patriotism and nationalism become synonymous to responsibility and pride of all Egyptians. His public discourse has tried exploited this emotional symbolism with a clear intent to show empathy with people’s sentiments. To help create this emotional common ground, he has used propaganda coupled with ‘passionate’ speeches against the “enemies” of the country (i.e. as in the Nasser era, the Muslim Brotherhood has been accused of treason against the state); and regaining local allegiance by means of mega infrastructure projects, such as the New Suez Canal expansion – that was entirely overseen by the EAF – or the ambitious plan to create 1.5 million acres of farmable land in the Western Desert, as well as to build two “smart” and ecological cities in Aswan and Alamein or the new administrative capital near Cairo.

Sisi has thus been able to explain his strategy by re-evoking positive feelings for the lost glories of the Nasser era and its peculiar form of nationalistic thinking(24). Although nationalism and patriotism are different, these terms share a common factor of unity based on a collective and widespread loyalty to the idea of state. These ideologies serve the purposes of the regime, in which nationalistic and patriotic rhetoric has been useful in exploiting political divisions in the country. Sisi and his advisors have invested in the same political and socio-economic strategies, adopted during Nasser’s presidency, to help glorify “Rais’s” [President] legacy as well as celebrate Sisi’s popularity through a form of misguided patriotism. However, recent terrorist events and worsening economic conditions, as well as increasing social discontent, may suggest that the restoration of a fierce nationalistic sentiment may not be enough to cultivate the illusion of a strong and resilient state. There are significant differences between Nasser’s and Sisi’s visions of nationalism(25). This authoritarianism mixed with militaristic nationalism is forging a new populist rhetoric aimed at maintaining control over society.

Sinai as a symbol of militaristic Egyptian nationalism

Sisi’s regime has made good use of the counterterrorism discourse as a propaganda tool. The war on terror and the fight against the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) and any form of Political Islam, without distinction, are great opportunities for the declared Egyptian patriotism. It is possible to test the strength of national sentiment against a threat. It is also a key factor to understanding the level of the militaristically exploited nationalism. Moreover, social conflicts, violent insurgency and the growth of Islamist groups have been instrumental tools for the establishment of certain authoritarian policies. Recent developments in the Sinai Peninsula highlight all these issues. The Egyptian media, while depicting Sinai as a line-in-the-sand marker that should be defended against the ‘enemies of the state’ (i.e. Islamist militants and Salafi-Jihadist groups), have promoted the counterterrorism narrative. However as Ivan Sand noted, “it is possible to identify two representations of this region that, in principle, seem antagonistic. On one hand, Sinai is presented as a neglected zone in terms of economic and social affairs, and on the other, as a highly coveted region from a geostrategic perspective. Far from being contradictory, these two visions of the peninsula are in fact interconnected and built on the same historical and geographical foundations”(26).

Since Egypt’s defeat in the Six-Day War in 1967 when Sinai fell under Israeli control, Egypt has sought to restore its sovereignty over the area, whereas this region is actually an inseparable part of the country. For over 30 years after the Israeli withdrawal from the peninsula in 1982 as according to the Camp David Accords, Sinai remained underdeveloped and gradually shifted into a borderland rather than an integral part of Egypt. Since 2012 when the Muslim Brotherhood rose to power, violent extremism spread in Sinai; and the perception of the Peninsula changed steadily from a neglected land to a dangerous zone. Nevertheless, if it was not enough to fuel false myth in 2013. Several domestic media announced a hardly plausible territorial transfer of the Sinai Peninsula from Egyptian control to that of the National Palestinian Authority (NPA), reviving the strong patriotic/nationalistic rhetoric. Moreover, several former Egyptian generals affirmed that the Muslim Brotherhood sponsored the Sinai jihadists and helped them and other criminals to escape from Egyptian security prisons. At this point, the discussion took a sharp turn and began focusing on the armed insurgency increasingly threatening the country and on the emerging risk of the birth of a new Afghanistan under the banner of violent Islamism in the Peninsula. The Muslim Brotherhood became merely the excuse; and help to divert the media and popular attention from the main vulnerabilities of the state. According to the official rhetoric, Sinai “has become an element of national pride that calls for the patriotism of each Egyptian citizen”(27).

New Ticking Time bomb?

Four years after the ousting Morsi, Egypt seems to be far from the promise of political stability and economic prosperity pledged by Sisi in 2014. This regime’s weakness and fragility has stimulated an alternative pushing for the militarization of the state apparatus and, consequently, escalated levels of violence against Egyptians. The War-on-Terror discourse and Operation Sinai-2018 are a perfect tool of distraction that might open a long-lasting attempt to institutionalize a securitization policy at all levels. Considering the failure of the counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism strategies in Sinai and in general in the country, this situation reveal the challenges facing the local authorities in promoting a transformative shift in the state apparatus and Egyptian society. In fact, there is a serious risk of a revival of a full-scale military dictatorship, and unfortunately, Sisi seems to have had little interest in turning the tide.

(1) Communiqué 2 – Army: Operation Sinai 2018 continues to end terrorism (February 10, 2018). State Information Service. Available at http://www.sis.gov.eg/Story/124495?lang=en-us (Accessed March 7, 2018).

(2) Magdy, Muhammad (February 20, 2018). Egypt steps up military operations in Sinai ahead of elections. Al Monitor. Available at http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2018/02/egypt-military-operation-sinai-sisi-elections.html#ixzz5958wpntN (Accessed March 7, 2018).

(3) For more information over Gaza Distribution of Rocket Hits see “News of Terrorism and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict (December 27, 2017 – January 2, 2018)” (January 3, 2018). The Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center. Available at http://www.terrorism-info.org.il/en/news-of-terrorism-and-the-israeli-palestinian-conflict-december-27-2017-january-2-2018/ (Accessed March 11, 2018).

(4) Kirkpatrick, David D. (February 3, 218). Secret Alliance: Israel Carries Out Airstrikes in Egypt, With Cairo’s O.K. The New York Times. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/03/world/middleeast/israel-airstrikes-sinai-egypt.html (Accessed March 9, 2018). For more information on Israel terror of threat see also Dentice, Giuseppe (October 20, 2016). “From Sinai to Negev: the growing terrorist threat in southern Israel”. Italian Institute for Political International Studies (ISPI). Available at http://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/sinai-negev-growing-terrorist-threat-southern-israel-15883 (Accessed March 9, 2018).

(5) Shay, Shaul (February 11, 218). Operation Sinai 2018: Egypt Escalates Military Operations against Terrorism. Israel Defense. Available at http://www.israeldefense.co.il/en/node/33025 (Accessed March 7, 2018).

(6) Magdy, Muhammad (February 20, 2018). cit. (Accessed March 8, 2018).

(7) An indirectly confirm the relevance of this argument is a video by militant allegedly connect to Wilayat Sinai released on Telegram three days after the start of the operation, in which these members threatened to target polling stations in Egypt. For more information see: Islamic State calls for attacks to disrupt Egypt elections (February 12, 2018). The New Arab. Available at https://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/news/2018/2/12/islamic-state-calls-for-attacks-to-disrupt-egypt-elections (Accessed March 7, 2018).

(8) Springborg, Robert (February 2018). “The riddle of the Sphinx: why President Sisi fears the election”. Middle East and North Africa Regional Architecture (MENARA Project). Future Notes No. 8. Available at http://www.menaraproject.eu/portfolio_category/future-notes/ (Accessed March 11, 2018).

(9) ‘Operation Sinai 2018’: What we know so far (February 9, 2018). Mada Masr. Available at https://www.madamasr.com/en/2018/02/09/feature/politics/operation-sinai-2018-what-we-know-so-far/ (Accessed March 8, 2018).

(10) Eleiba, Ahmed (March 8, 2018). Sinai 2018: A month on. Ahramonline. Available at http://english.ahram.org.eg/News/292400.aspx.

(11) “ISIS warns Egyptians to stay away from the election centers during the Egyptian presidential elections” (March 14, 2018). The Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center. Available at http://www.terrorism-info.org.il/en/isis-warns-egyptians-stay-away-election-centers-egyptian-presidential-elections/ (Accessed March 15, 2018).

(12) Ragharvan, Sudarsan (September 2017, 15). Egypt’s long, bloody fight against the Islamic State in Sinai is going nowhere. The Washington Post. Available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/egypts-long-bloody-fight-against-the-islamic-state-in-sinai-is-going-nowhere/2017/09/15/768082a0-97fb-11e7-af6a-6555caaeb8dc_story.html?utm_term=.a32a21bf620c (Accessed March 18, 2018). See also, McManus, Allison (July 2017, 27). “Measuring Success in Egypt’s War on Terror”. The Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy (TIMEP). Available at https://timep.org/commentary/measuring-success-in-egypts-war-on-terror/ (Accessed March 18, 2018).

(13) For more information on Egyptian terror context see Dentice, Giuseppe (February 2018). “The Geopolitics of Violent Extremism: The Case of Sinai”. European Institute of the Mediterranean (IEMed). 36 Papers IEMed. Available at: https://www.euromesco.net/publication/the-geopolitics-of-violent-extremism-the-case-of-sinai/ (Accessed March 11, 2018).

(14) Sinai residents suffer, a month into Egypt’s military campaign (March 13, 2018). The New Arab. Available at https://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/society/2018/3/13/sinai-residents-suffer-a-month-into-egypts-military-campaign (Accessed March 18, 2018).

(15) Gold, Zack (April, 2016). “Salafi Jihadist Violence in Egypt’s North Sinai: From Local Insurgency to Islamic State Province”. The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague, 7, no. 3. Available at http://icct.nl/publication/salafi-jihadist-violence-in-egypts-north-sinaifrom-local-insurgency-to-islamic-state-province/ (Accessed March 11, 2018).

(16) For more information on the dynamics between local population and terror groups see Ashour, Omar (2015, November 8). Sinai’s stubborn insurgency: Why Egypt can’t win. In “Foreign Affairs”. Available at https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/egypt/2015-11-08/sinais-stubborn-insurgency (March 11, 2018); Gleis, Jonathan (June, 2007). Trafficking and the role of the Sinai Bedouin. In “Jamestown Foundation-Terrorism Monitor”, 5(12). Available at https://jamestown.org/program/trafficking-and-the-role-of-thesinai-bedouin/ (Accessed March 11, 2018).

(17) Hamzawy, Amr (March 16, 2017). “Legislating Authoritarianism: Egypt’s New Era of Repression”. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Carnegie Papers No. 302. Available at http://carnegieendowment.org/2017/03/16/legislating-authoritarianism-egypt-s-new-era-of-repression-pub-68285 (Accessed March 11, 2018).

(18) Winter, Ofir, & Malter, Meirav (August 24, 2017). “Egypt’s challenging shift from counterterrorism to counterinsurgency in the Sinai”. Institute for National Security Studies (INSS). INSS Insight, 968. Available at http://www.inss.org.il/publication/egypts-challengingshift-counterterrorism-counterinsurgency-sinai/ (Accessed March 11, 2018).

(19) Brown, Nathan J. & al-Sedany (October 30, 2017). How a State of Emergency Became Egypt’s New Normal, The Washington Post. Available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/10/30/how-a-state-of-emergency-became-egypts-new-normal/?utm_term=.ca00449a70a0 (Accessed March 11, 2018).

(20) Roll. Stephan, (October 12, 2015). Managing change: how Egypt’s military leadership shaped the transformation. In “Mediterranean Politics” 21:1, 23-43. Available at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13629395.2015.1081452 (Accessed March 11, 2018).

(21) Cook, Steven A. (November/December, 2016). Egypt’s Nightmare, Sisi’s Dangerous War on Terror. In “Foreign Affairs”. Available at https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/middle-east/egypt-s-nightmare (Accessed March 11, 2018).

(22) See Abul-Magd, Zeinab (July 25, 2014). “Militarism, Neoliberalism, and Revolution in Egypt” in N. Hopkins (ed. by) The Political Economy of the New Egyptian Republic. The American University in Cairo Press, pp.153-173, Cairo.

(23) Lutterbeck, Derek (April, 2015). The Role of Armed Forces in the Arab Uprisings. University of Malta, pp. 162-164. Available at https://www.um.edu.mt/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/150405/Chapter_9_-_Derek_Lutterbeck.pdf. (Accessed March 11, 2018).

(24) El-Benni, Saleh (June 10, 2017). Militaristic Egyptian Nationalism, from Nasser to el-Sisi: PART 1. The Politic. Available at http://thepolitic.org/militaristic-egyptian-nationalism-from-nasser-to-el-sisi-part-1/ (Accessed March 12, 2018)

(25) According to Zeinab Adel-Magd, “The old and new armies differ in their socioeconomic composition, doctrine, and the way they militarized society”. Moreover The Nasser idea of nationalism was based on pan-Arabism, in which Egypt was presented as the leader of Sunni-Arab World against the Western countries, while the al-Sisi’s vision of nationalism is onward looking and aimed to a prioritization of Egyptian security interests in the regional context. See Abul-Magd, Zeinab (July 25, 2014). cit. (Accessed March 11, 2018). For more information see also, El-Benni, Saleh (June 10, 2017). Militaristic Egyptian Nationalism, from Nasser to el-Sisi: PART 2. The Politic. Available at http://thepolitic.org/militaristic-egyptian-nationalism-from-nasser-to-el-sisi-part-1/ (Accessed March 12, 2018)

(26) Sand, Ivan (January, 2016). Représentations géopolitiques du Sinaï dans trois titres de presse. In “L’Espace géographique”, 2016/1 (Volume 45), p. 44-60. Available at https://www.cairn.info/revue-espace-geographique-2016-1-p-44.htm (Accessed March 14, 2018).

(27) Sand, Ivan (January, 2016). cit. (Accessed March 14, 2018).