Abstract

Elections have been at the very heart of the expectations of African domecratization since they have served some critical democratic purposes, most notably the promotion of political participation, competition and legitimacy, which are pivotal to democratic consolidation.(1) While ‘elections do not, in and of themselves, constitute a consolidated democracy’, Michael Bratton argues that they, however, ‘remain fundamental, not only for installing democratic governments, but as a necessary requisite, for broader democratic consolidation’.(2) Yet, elections can also be used to disguise authoritarian rule, a form of democratic ritual that does not actually guarantee freedom of choice.

The conflicting trajectories of democratic transitions in Africa remain a source of concern. This paper reflects on trajectories of democratic transitions in Africa, underscoring the different paths/forms of transitions. It also offers explanations for the success and failure of democratic transitions in Africa, with empirical illustrations drawn from Ghana, Nigeria, Senegal and Zambia. For comparative insight, a few cases are referenced from the Arab world: Libya, Egypt, and Tunisia. It also showcases how the history of democratic transition in Africa is varied and chequered, much as the trajectories, it has assumed in different places and time, are many and complex.

Introduction

The 1990s approximates the age of democratic rebirth in Africa during which many African countries witnessed a massive resurgence of electoral democracy after decades of authoritarian rule and bad governance.

(3) This was made possible by years of internal and external pressure, including popular discontent with economic hardship and political repression, which accentuated demand for political/democratic reform in the 1990s.(4) As the third wave of democratization spread across Africa, expectations were high that the transition to democracy, which followed different ‘paths’, would lead to the consolidation of democracy and development on the continent.

Almost three decades into the democratic journey while some countries have made steady progress in terms of holding regular elections and deepening democracy, many others have not been so successful. In fact, a few could be said to have backslidden. As the Economic Commission for Africa notes in its African Governance Report (AGR) II, “Since the foundation of elections in the 1980s there have been numerous elections in Africa. But many countries have not had quality elections. Overall there has been notable progress on political governance in some countries, while improvements have been blunted or reversed on others. On balance the progress on political governance has been marginal.”(5)

Models of Democratic Transition in Africa

Democratic transition generally connotes the movement from a less democratic order (authoritarianism in its diverse forms) to a more liberal democratic society, where democratic values (periodic, free, fair and credible elections; rule of law; independent judiciary; vibrant civil society; free, open and independent press; stable civil-military relations, etc.) become the only acceptable ways of organising society. Transitions to democracy usually takes two forms or modes, namely transition from above and transition from below. The former is leadership-driven (usually state-centric) and connotes a situation where leaders respond to prevailing realities by initiating democratic reform; the latter is people-driven (societal led) and represents popular pressures for democratic reforms, especially inspired by robust civil society.(6) While these two modes are well recognized, the possibility of fusion of elements of both modes of transition into one case cannot be overlooked.

It is pertinent to note that while transition from above has been credited with greater ability to deliver democracy, especially in terms of higher tendency to be ‘more specific about their time frame, procedural steps, and overall strategy’, transition from below is said to be characterized with ‘a great deal of uncertainty’. These qualifications are surprising, given that all forms of transitions, be it from above or below, contain elements of uncertainty. In both instances, the manipulative abilities of the transitional leaders, including their commitment to democratic reform and rebirth, may never be known in clear terms. The intervening role of some anti-democratic forces too can also serve to undermine, delay or prolong the transition process.

In the African context, experiences have shown that democratic transitions have been inspired mainly from below. Under this variant, about four different strands of transition have been identified. These are: a) national conferences; b) popular revolutions; c) pact formation; and d) actions by the military. While each of these models has specific attributes, it is important to note that in many instances, there were overlaps where two or more models were reflected in one transition.

Take national conferences, for example. The most notable cases were recorded mainly but not exclusively in Francophone Africa such as Benin, Gabon, Mali and Togo. Nigeria and Zambia also had national conferences at one time or the other. Such conferences were also a product of popular pressure for national dialogue and democratic reforms. Popular revolutions are primarily championed by the people (especially civil society organizations) demanding for the expansion of the democratic space. While this model was pervasive in the 1990s, the most recent illustrations remain the popular uprisings in North Africa that consumed longstanding authoritarian regimes.(7)

Pact formation (such as South Africa) involves agreement between the departing authoritarian regime and the incoming democratic leaders, particularly about immunity from prosecution of key officials of the departing government, regarding aberrations issues such as human rights violations, corruption and crimes against humanity, among others.

Ultimately, irrespective of the adopted model, transitions often dovetail into elections. This partly explains why much emphasis has been placed on democratization by election.(8)And from a minimalist point of view, elections remains at the very heart of democratization. The import of this is that the success or failure of the transition processes depends largely on the democratic qualities of elections, measured by the degree of political participation, competition and legitimacy.

|

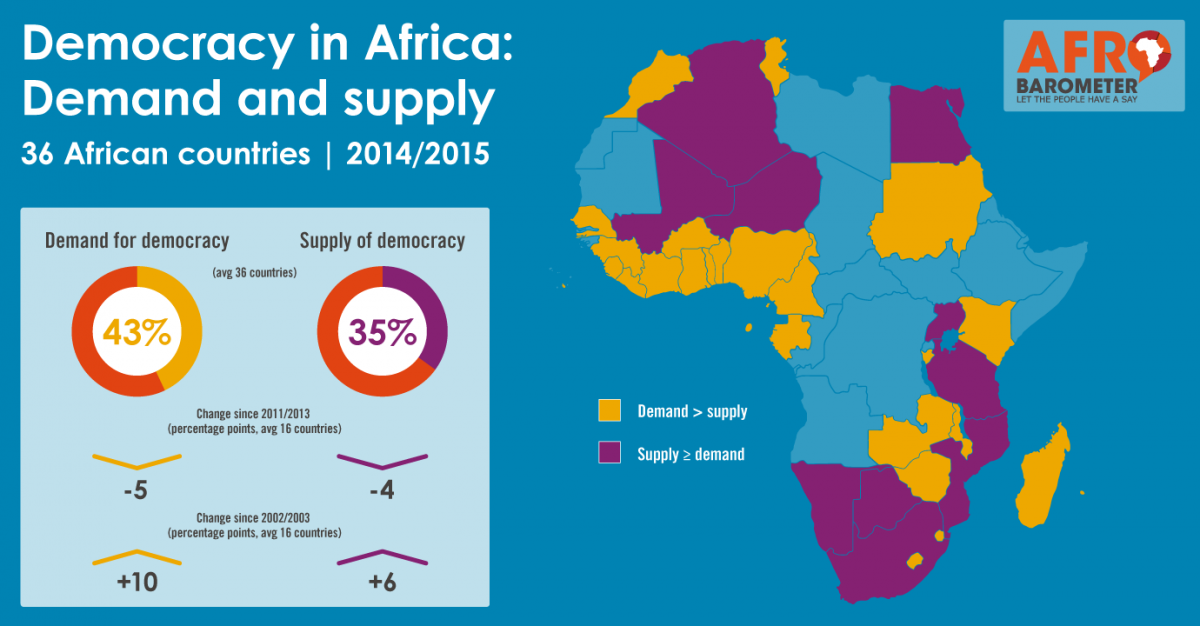

| Democracy in Africa: Demand and Supply, 2014/15 [Source: Africa Barometer] |

Most Promising Democratic Transitions in Africa

From a minimalist perspective, while some countries have made steady progress in democratization by election, many others have not. Among the most successful cases include Ghana, Nigeria, Zambia and Senegal. In Ghana, for example, despite the challenges of the founding election of 1992, the country has made great leap forward in its democratic transitions.(9) The major highlights of its transitional success include the regularity, freeness and fairness, credibility and peacefulness of its elections, the high level of competition involved in the elections, epitomized by not only the usually low margin of votes between the winning party and the runner-up, but also the almost evenly distribution of seats between the two leading parties in parliament, the frequency of alternation of power so much so that opposition parties have won elections on three different occasions (2000, 2008, 2016). Impressively, these alternations also featured the defeat of an incumbent president in 2016, a very rare feat in African democracies.

Nigeria’s case has been slightly different. Initially characterized by ineffective governance of the electoral processes, culminating in diverse forms of electoral corruption such as discredited voters register, lack of internal party democracy, snatching and stuffing of ballot boxes, outright falsification of election results and heavy violence at all stages of the election (before, during and after), a series of electoral reforms that strengthened the autonomy and administrative capacity of the electoral management bodies (EMB), the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), have, in addition to other factors to be highlighted shortly, resulted in steady improvement in the overall electoral environment of the country.(10) The positive electoral trend peaked in 2015 with not just the alternation of power, but more importantly, the electoral defeat of the incumbent president, Goodluck Jonathan.(11) Both feats were unprecedented in Nigeria’s electoral history.

|

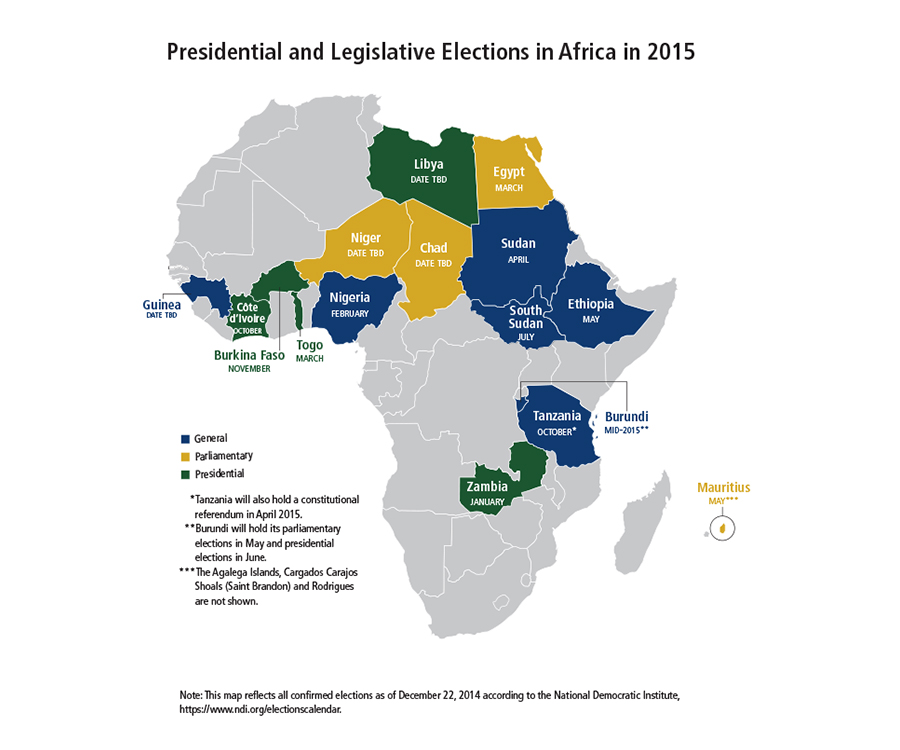

| African Elections in 2015 [National Democratic Institute] |

In others countries, including Liberia, Senegal and Zambia, some of the distinguishing features of democratic progress include the regularity of elections, high level of competition, alternation of power and defeat of incumbents. The high degree of completion manifested in diverse ways. In Liberia and Senegal, for examples, winners could not emerge in the first round of the presidential elections in 2018 and 2012 respectively. Moreover, both elections also resulted in alternation of power with the defeat of the incumbent party. In the case of Senegal, the 2012 election culminated in the defeat of incumbent President Abdulaye Wade, who lost to Macky Sall of the Alliance for the Republik (APR).(12) In the case of Zambia, Michael Sata defeated incumbent president Rupiah Banda in the 2011 presidential election.(13)

However, democratic transitions have not taken firm roots in some cases. This is particularly the case in Arab countries in North Africa, most notably Egypt and Libya. In most of these cases, the political spaces have been severely constrained and suffocated by the existence of longstanding authoritarian regimes. Authoritarian tendencies manifest in these countries in diverse ways, including dictatorship.

The so-called “Arab Spring” has raised expectations about the prospects of a new dawn of democratic rebirth. Such expectations are understandable given that the uprisings were from below, largely people-driven, with the activism of a broad spectrum of society. But, as already established in the literature, revolutions do not always lead to sustainable democratic transitions. Egypt represent the closest approximation of this reality.

In Egypt, the election of Mohamed Morsi under the platform of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party (FJP) has not gone to expectations. Instead, it has led to polarization and violence and eventual military usurpation of power under the leadership of General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. It has been posited that “the level of repression under President Abdel Fattah al-Sissi surpasses that of President Hosni Mubarak and even his predecessors, in terms of the number of Egyptians killed, wounded, detained, and ‘disappeared’ since the military coup of July 3, 2013”.(14) The military junta is reported to have killed over ‘1,000 civilians, imprisoned tens of thousands more, and cracked down on media and civil society’.(15)

The situation in Libya is worse off. The Western-backed ousting and eventually killing of Muammar Gaddafi in the so-called people-driven revolution for the enthronement of democracy seems to have backfired. The level of attendant contradictions, including unprecedented fractionalization, destruction of political institutions, proliferation of small arms and light weapons, and general atmosphere of instability, characterized by massive violation of human rights, have combined to scuttle all efforts geared toward sustainable peace-building and democratization.(16) Although the Tunisian experience has been generally considered to be better in terms of the increased liberalization of the political space, yet concerns still abound regarding the quality of the transition.(17)

Overall, Dworkin aptly summarises the challenges in these countries thus, “The political transitions in North Africa appear to be faltering. …these early stages of democratic politics now seem to show the dangers of political competition as much as its benefits. The revolutions inspired the hope that these countries could build political systems that fostered national unity by drawing on the contribution of all their citizens. But developments in recent months in all three countries make that aspiration seem like a distant prospect.”(18)

The foregoing exposes the different trajectories of democratic transitions with notable successes and setbacks. The he next section offers explanations for the success and failure of democratic transitions in different regions of Africa.

What Success, What Failure?

The success of democratic transitions in the highlighted cases can be explained by many factors. These include the independence and professionalism of the EMBs, opposition coordination, the growing assertiveness of citizens, increasing accessibility and usage of the social media and new technologies, and the supportive role of international community, among others.

In Ghana and recently Nigeria, the autonomy of the electoral commission, has enabled them to assert some reasonable degree of authority over the electoral cycle and processes. A series of electoral reform initiatives have also boosted the professionalism, administrative capability and efficiency of the EMB in both countries. For example, the implementation of critical recommendations from the report of the Justice Uwais Electoral Reform Committee was particularly pertinent in the Nigerian case. In Ghana, the Chairperson of the Electoral Commission is statutorily endowed with security of tenure of office so much so that once appointed, the president could no longer remove him except for ‘gross violation’ of the constitution.

Moreover, in most of the successful cases, especially those that have experience alternation of power and/or defeat of incumbent presidents, a common denominator has been effective coordination of opposition parties. This factor was of great significance in the 2015 general election in Nigeria during which leading opposition parties merged and were able to pull resources together, better coordinate the activities, all leading to the electoral success of the opposition.(19)

Also critical to the democratic success in these countries is the rise of an increasingly assertive citizens. Voters seem no longer contented with just casting their votes, they have also begun to demonstrate keen interest in what happens to their votes. In other words, citizens want to do all within the law to ensure that their votes truly count, unlike what obtained in the past, especially in Nigeria until 2011. At least three factors may have contributed to this development. First, there abound many CSOs devoted to the promotion of democratic values that engage in voter education and critical engagements with core electoral stakeholders such as the electoral commission, political parties and security agencies. The Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD), CLEEN Foundation, Youth Initiative for Advocacy, Growth and Advancement (YIAGA) represents critical examples in Nigeria. Second, there has been a substantial rise in the level of access and use of the social media and new technologies in these countries. Tools such as the internet, mobile phones, facebook, twitter have become powerful mobilization tools in such countries. Also to a very large extent, the international community has been very supportive of the democratization processes through technical and financial assistance to the electoral commissions of these countries.

|

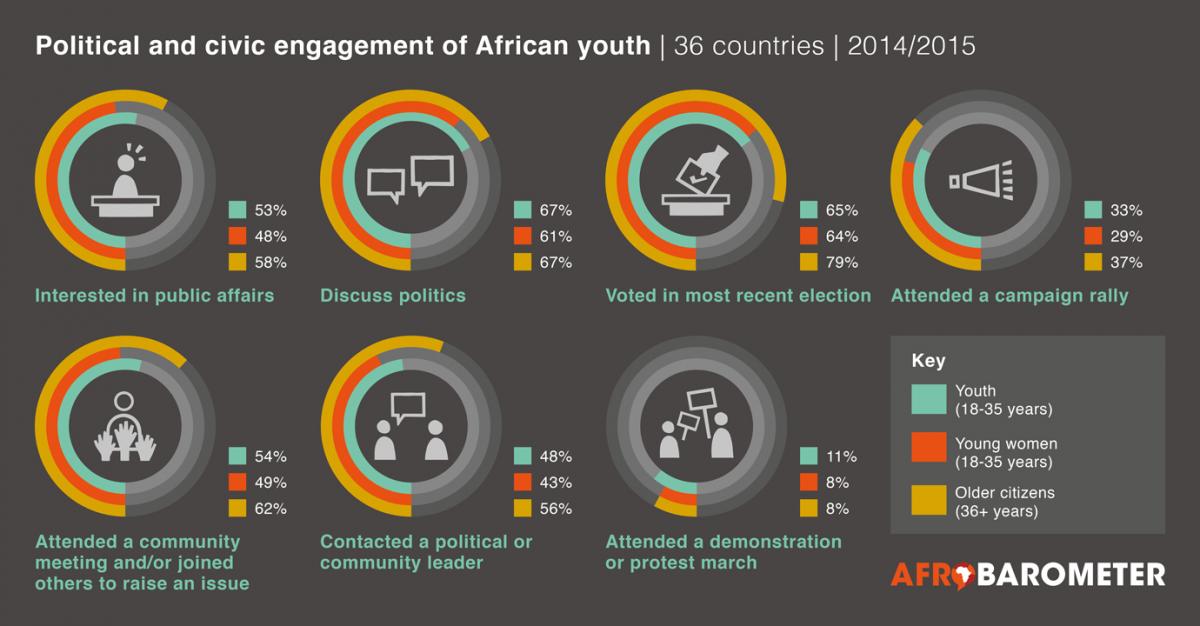

| Political and Civil Participation of African Youth, 2014/15 [Africa Barometer] |

In North Africa, some of these enabling conditions are either lacking or in short supply, underscoring their limited democratic credentials. More specifically, democratic failures in the Arab countries, particularly Egypt, Libya and Tunisia, is not unconnected with a long legacy of authoritarianism, weak economic foundations, lack of a clear idea by leaders of the revolution, lack of accountability mechanisms, and fragmented opposition, among others.

That North Africa has a long history of authoritarian rule is a settled matter in the literature. For whatever reason, people tolerated the dictatorial dispositions of these regimes. However, as the ‘economic legitimacy’ of autocracy continued to wane sharply to the extent that ‘the cost of autocracy’ could ‘no longer compensate for the meagre economic benefits delivered by North African governments’ it was only a matter of time that the foundations of those dictatorial regimes would be shaken. This happened with the Arab spring of 2011. Not quite unexpectedly, the faltering of the high prospects placed on the revolt as a promising path out of poverty and inequality meant that popular discontents with the ‘new democracies’ could not be delayed for long. The result has been increasing unprecedented fragmentation of society along tribal and religious lines.

The failure of some of these transitional regimes to also promote accountability, particularly by addressing the legacies of decades of dictatorships through transitional justice initiatives, has only served to complicate the problem. Such an initiative would have helped address long-standing human rights abuses and related grievances. To better appreciate the salience of this factor, it is important to note that the much touted Tunisian exceptionalism has been partly explained in terms of its ‘broad societal consultation on transitional justice’, leading to the drafting of a transitional justice law in the country. Egypt and Libya failed woefully in this respect.

Yet, opposition parties would appear not to have learnt any serious lessons from the successful cases elsewhere on the continent. They remain largely fragmented. Granted that uniting the opposition is not self-sufficient, there is strength in unity and that could be a good starting point.

Conclusion: The Promise of Transition

This analytical paper has showcased that the history of democratic transition in Africa is varied and chequered, much as the trajectory it has assumed in different places and time are many and complex. Transition success stories have been seen in some countries such as Ghana, Nigeria, Senegal and Zambia, though not without some notable hitches and setbacks. However, in other cases like Tunisia, the promise of the Arab uprising in ushering transition to genuine democracy failed to materialise. To deepen democracy in Africa, there is the need to capacitate institutions critical to the conduct of free and fair elections, strengthen structures that institutionalise peaceful political transition, encourage strong ideologically based political parties, energize civil society, expand avenues for greater political inclusion, and build strong regional normative frameworks against authoritarianism.

|

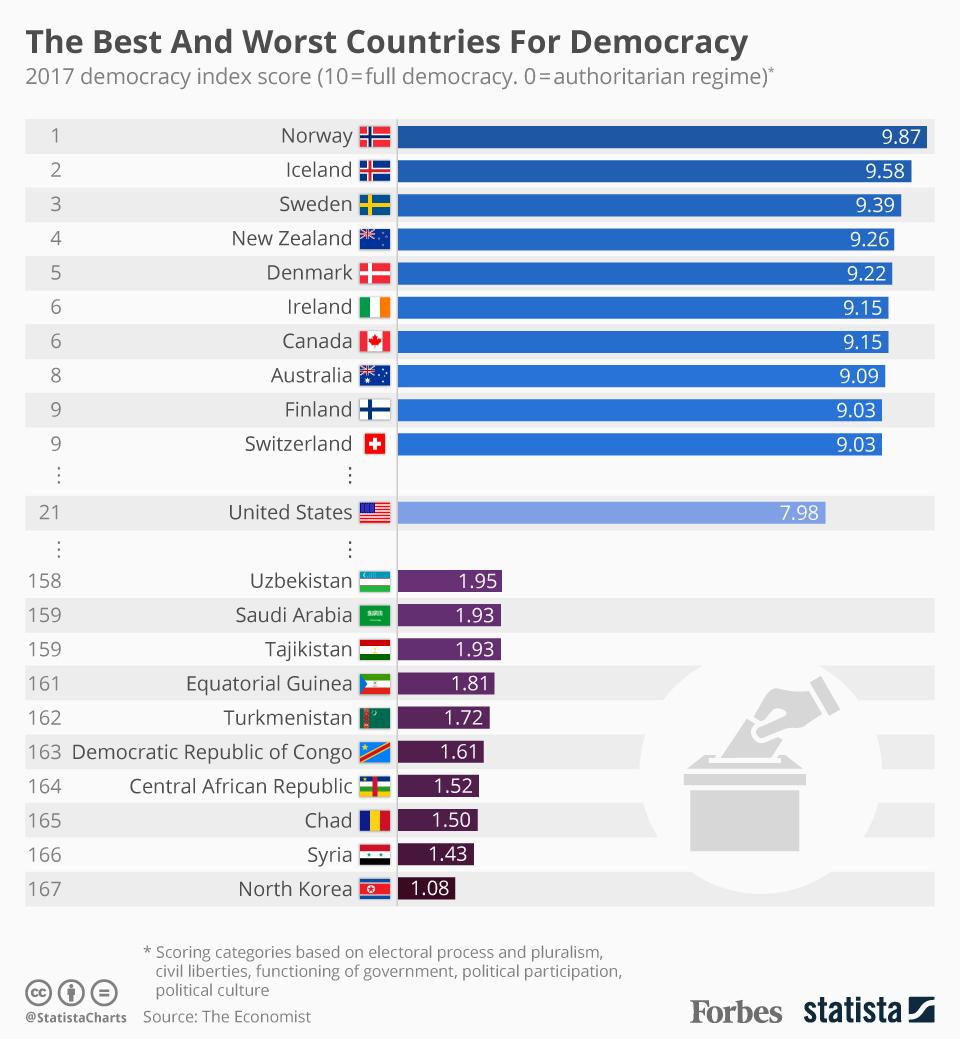

| The Best and Worst Countries for Democracy [Statista] |

(1) Staffan Lindberg, (2009) 'A Theory of Elections as a Mode of Transition', in Lindberg, Staffan (ed.)

Democratization by Elections: A New Mode of Transition? Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

(2) Michael Bratton, (1998) ‘Second Elections in Africa’, Journal of Democracy, 3 p. 52.

(3) Michael Bratton, Nicholas van de Walle, (1997) Democratic Experiments in Africa: Regime Transitions in Comparative Perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press.

(4) Gabrielle Lynch and Gordon Crawford, (2011) “Democratization in Africa 1990–2010: An Assessment,” Democratization. 18(2): 275–310.

(5) Economic Commission for Africa, (2009), African Governance Report (AGR) II. New York: Oxford University Press, p.17.

(6) National Research Council, (1992) Democratization in Africa: African Views, African Voices. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

(7) Amir Taheri, (2012) 'The Future of the Arab Spring: Best-Case Scenario, Worst- Case Scenario', American Foreign Policy Interests: The Journal of the National Committee on American Foreign Policy, 34:6, 302-308.

(8) Jeremiah S Omotola, (2014), The African Union and the Promotion of Democratic Values in Africa: An Electoral Perspective, Johannesburg, SA: South African Institute of International Affairs, Occasional Paper 185.

(9) See for instance, Abdul-Gafaru Abdulai, and Crawford Gordon, (2010) 'Consolidating Democracy in Ghana: Progress and Prospects', Democratization, 17(1):26–67.

(10) Jeremiah. S, Omotola, (2013) ‘Trapped in Transition: Nigeria’s First Democratic Decade and Beyond’, Taiwan Journal of Democracy, Vol. 9 (2) Taiwan Foundation for democracy, Taiwan, pp. 171-200.

(11) Freedom C. Onuoha, Christian M. Ichite, and Temilola A. George, (2015) Political, Economic and Security Challenges facing President Buhari. Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, 21 September.

(12) Arame Tall, (2012), 'Democracy wins in Senegal', Aljazeera, 26 March, https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2012/03/2012326133458592301.html

(13) Jeremiah S. Omotola, and A. Stroh, (2017), ‘Presidential Elections, Incumbent Losers and Political Institutionalisation in Africa’, Draft paper, Bayreuth International Graduate School of African Studies (BIGSAS), University of Bayreuth, Germany, November.

(14). Carl Gershman, (2016) 'Islam and Democracy after the Arab Spring', World Affairs, http://www.worldaffairsjournal.org/article/islam-and-democracy-after-arab-spring

(15). Abraham F. Lowenthal, and Sergio Bitar, (2016) 'Getting to Democracy: Lessons From Successful Transitions', Foreign Affairs, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2015-12-14/getting-democracy

(16) Ricardo Larémont, (2013) 'After the Fall of Qaddafi: Political, Economic, and Security Consequences for Libya, Mali, Niger, and Algeria', Stability: International Journal of Security & Development, 2(29): 1-8.

(17) Freedom House, (2011) 'Outlook for Democracy in Post-uprising North Africa', 10 November, https://freedomhouse.org/blog/outlook-democracy-post-uprising-north-africa

(18) Anthony Dworkin, (2013) The Struggle for Pluralism after the North African Revolution, London: the European Council on Foreign Relations, p.13

(19) Hamalai, L., Samuel G. Egwu, and Jeremiah S. Omotola, (2017) Nigeria’s 2017 General Elections:Continuity and Change in Electoral Democracy, UK: Palgrave Macmillan