President Donald Trump is considering holding a second summit with Chairman Kim Jong-un “sometime next year, sometime early next year [2019].” (1) The Trump-Kim relationship, which was clearly an attitude of mutual diversion at first, has now entered a new phase. Russia and China are providing major support to North Korea, with the aim of holding a five-way round of talks including South Korea and the United States. (2) Since heading his new government in 2012, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe appears to be cut out of the loop despite his ‘new level of pressure’.

This paper probes into two main questions. A) why does Japan stick to pressure on North Korea despite its isolation from the international community? This question calls for an attempt to elucidate the reasons for Japan’s persistence to sanctions on Pyongyang in the context of Prime Minister Abe’s ideological paradigm and the trajectory of his North Korea policy. B) how will the US-North Korea summit develop in the future? This query will address some outstanding issues that tend to shape the view of Tokyo about denuclearization modalities in North Korea.

Intoduction

During their talks in Moscow October 9, 2018, deputy foreign ministers representing Russia, China, and North Korea held on the imperative of including the United States and South Korea in future five-member talks. The focus remains on possible ways of the denuclearization of North Korea. South Korea’s President Moon Jae-in had a summit with Kim Jong-un and announced the historic Panmunjom Declaration late April. Donald Trump had a face-to-face summit with Kim Jong-un in mid-June.(3) Another significant shift in the contextualization of the upcoming second summit is its timing, as the Trump administration indicated, after the midterm elections held November 6, 2018. As the five-way talks with South Korea may give some compromises to North Korea, the United States may have to soften its position vis-à-vis the desired denuclearization declaration; whereas China and Russia have conventionally supported North Korea.

However, the position of Japan remains rather stiff about reinforcing sanctions against North Korea and looks left out of the international community that is calling for cooperation toward denuclearization of North Korea. Japan has rejected the ‘wisdom’ of holding any dialogue with North Korea. Kim Jong-un was quoted saying “Why doesn’t Prime Minister of Japan make a direct contact with us?”(4) If this statement is factual, it implies Tokyo has no direct negotiation channel with Pyongyang.

Japan has faced several North Korean threats of nuclear and missile development, while struggling with the frequent abduction of Japanese citizens by North Korean authorities inside Japan’s territories. Consequently, Tokyo continues to reinforce the UN sanctions and other independent sanctions against North Korea. With the Chinese-Russian-North Korea alliance, Seoul has pushed forward to reaching a reconciliation accord with Pyongyang since President Moon took office. These nations promote dialogue with Pyongyang and the international community welcomes Pyongyang’s intention for denuclearization.

The question now is why Tokyo alone keeps its persistent call for a “new level of pressure”. (5) There is some irony: Japan which has sought to impose isolation on North Korea seems to find itself isolated. It is also worth probing into what kind of political discourse Tokyo has constructed about the denuclearization plan of North Korea. How will the denuclearization process develop between Trump and Kim? What is the obstacle to achieving this objective? These questions derive from the context of the relationship between North Korea and Japan.

Abe’s Ideological Position

The once-unified Korean dynasty has a long history. It has been a tributary state of historical kingdoms in China until the end of the 19th century. As a result of the Sino-Japanese War, the defeated nation, Qing, ended the tributary state system. As a result, Korea emerged as an independent Korean Empire with some leaning toward Russia at the beginning. Japan managed to curtail the influence of Russia through the ‘Russo-Japanese War’ and annexed the Korean Empire to Japan in 1910.

During the following thirty-five years, Korea was ruled by Empire of Japan, which was later defeated in World War II. Subsequently, Korea was divided by two superpowers: at the 38th parallel north and the southern part from the northern latitude of 38 degree was occupied by the United States. The northern part from the latitude of 38 degree was occupied by the Soviet Union. Under the US military administration, the Republic of Korea was established in the southern part of the peninsula August 15, 1948; while North Korea gained independence September 8, 1948, from the Soviet Union, which had established the Provisional People’s Committee for North Korea.

Japan, South Korea, and North Korea share a history of sour relationship. The colonial residue of political differences remains effective in a regional cold war. From a Japanese perspective, the so-called ‘postwar reparation issue’ has deepened the Korean animosity where distant interpretations of history add to the complexity of the conflict. Japanese conservative elite and communities consider these Korean differences to be “history wars”, which tend to “humiliate their nationalist pride and dignity.” The tit-for-tat escalation remains high between Tokyo and Seoul. History has also preserved certain unfavorable memories among Japanese nationalists as they recall Kim Il-sung, the founding father of North Korea, for his anti-Japan doctrine of regional politics.

Similarly, the history of North Korea has gone through twists and turns since its independence vis-à-vis its neighbor Japan. The issue of abducted Japanese individuals in the 1970s and the 1980s often pushed the bilateral relations into escalatory exchange between the two capitals. 17 Japanese citizens were abducted by North Korea, which acknowledged officially the arrest of 13 of them. So far, only five abductees have returned to Japan, while the Japanese government has called persistently for the release of the remaining twelve individuals.(6) Prime Minister Abe also capitalized on this issue by framing a would-be solution in his electoral campaign. The abduction issue and nuclear development present security threats to Japan and are certainly critical, in particular, for the Abe administration which trying to revise the Constitution. North Korea withdrew from the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapon (NPT) in 1993 and also in 2003, after it resumed testing nuclear weapons in 2006.

Being drafted and adopted under occupation by the victorious nations following World War II, the Constitution of Japan specifies the renunciation of military power under Article 9. However, this constitutional commitment seems to contradict the presence of the ‘Self-Defense Forces (SDF)’, which are de facto armed forces of Japan. The conservative camp has argued the Constitution should be written once again by Japanese themselves. Prime Minister Abe has called for a thorough revisionist process especially in terms of Article 9 to help break away from the “postwar regime” philosophy.

His administration has adopted a rather hawkish stand, and seeks to solidify the country’s military industry. Mr. Abe has called for allocating more budget to maximize the potential of military research, which was prohibited in the postwar era. Abe has strategized the advocacy of the transformation of Japan’s military power, formulation of the national defense strategy, and the allocation of more money toward military research projects with the aim of gaining momentum for the amendment of the Constitution.

The rationale of Japan’s alternative worldview, shaped by Prime Minister Abe, derives from the perceived threats of North Korea and China. If Pyongyang builds some cooperative relationship with South Korea and advances the denuclearization project with the United States, these dynamics may end up weakening Abe’s plan, namely the expansion of the national military. One should also consider the implications of the postwar reparation issue and other salient differences within the Korean Peninsula and the whole region. Abe’s and other right-wing politicians and ideologues would not relinquish any of their nationalist expectations, let alone considering a particular compromise.

‘Perceived’ or ‘Real’ Threats… from North Korea?

Unlike the novelty of Trump’s presidency in the United States and Moon’s leadership of South Korea as recent as 2017, the premiership of Shinzo Abe has been robust for more than twelve years. His emergence as new Prime Minister in 2006 has not only coincided with, but also benefited from the North Korean nuclear tests inside the country. During his two terms in office [2006-2007] and [2012-present] so far, Abe has maintained a realpolitik view of his country’s regional and international relations. His ruling party, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), has deepened his anti-North Korea political skepticism.(7)

Since 2006, Japan has imposed sanctions on Pyongyang, when North Korea resumed its nuclear tests. Tokyo has also urged the UN Security Council to impose sanctions. (8) However after Kim Jong-un assumed the leadership after the death of his father in 2011, North Korean nuclear and missile tests increased significantly to a record number in 2017. Subsequently, Japan’s concerns grow more and more. Prime Minister Abe has become the international driving force for imposing more sanctions on North Korea. He has also been very keen on introducing a constitutional amendment and the growth of Japan’s military capabilities. While capitalizing on North Korean threats as well as the negative exchange between Trump and Kim before the White House accepted the summit invitation.

|

| [CSIS] |

In this context, Abe decided to rely on the 2007 national warning system, also known as “J-Alert”, which was originally set up to help address natural disasters, in disseminating information about the threats coming across the border with North Korea. Swiftly, the alarm system was loud enough to alert against possible missiles or terrorist attacks, instead of earthquakes or floods.

J-Alert is a warning system that rarely went off in Japan awaiting the proper time to be used. However in 2017, ear-splitting alarms captured the attention of the Japanese population, through their smartphones, after a North Korean missile was heading toward Japanese territories at 5:27 am (Pyongyang time) August 29, 2017. Japan’s J-Alert went off little after 6:00 am to wake up the country to the reality of attack and intimidation by their neighbors. Within hours, Prime Minister Abe issued a strong statement condemning North Korea, “Reckless action is an unprecedented, serious and a grave threat to our nation,” and called President Trump asking for an increase in pressure on North Korea. (9) Once again, J-Alert went off after another North Korean missile test September 15, as Mr. Abe used a more condemning tone toward North Korea, and pushed for an emergency session to be held at the UN Security Council immediately. (10)

The use of the J-Alert alarm twice within a short time helps explain to what extent the Japanese population has internalized feelings of fear and untrust. The effectiveness of the local governments’ crisis-management skills were questioned heavily, and the Liberal Democratic Party seemed to be struggling with some questions of scrutiny and accountability. (11) Abe’s government had spent approximately 400 million yen on a promotional campaign of the J-Alert on various TV channels. Obviously, such costly campaigns were aiming at manipulating the use of the J-Alert in spreading the impact of the perceived, an often inflated, threats coming from North Korea.

However by April 27, 2018, this trend came abruptly to an end. The so-called ‘Inter-Korean Summit’ between the two leaders of Koreas. North Korean leader Kim to his South Korean counterpart Moon, “I won’t interrupt your sleep” with early morning missiles test.(12) A few six weeks later, another news headline summit was held between Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un, the first meeting of high political altitude between the United States and North Korea in Singapore. This rapprochement was a historical-180-degree shift in the turbulent US-North Korean relations. It has also triggered some easiness among other nations vis-à-vis a possible containment of Pyongyang. However, Japan opted for continuing its campaign for more pressure on North Korea. Some observers have concluded the Trump-Kim summit has marginalized China’s influence on the Korean Peninsula issue as a whole. (13) Japan seems to be facing two hard choices: either supporting the international rapprochement with North Korea or maintaining the course of the sanctions advocacy of its neighbor!

Although Prime Minister Abe alluded to the possibility of holding a Japan-North Korea summit, “I want to get a chance.” But, he also cautioned “if a summit is held, this has to contribute to a solution to the abduction issue.” He emphasized the importance of a ‘comprehensive solution’ together with the nuclear and missile issues. (14) This statement can be interpreted as Abe’s indirect avoidance of the idea of a Japan-North Korea summit.

Abe’s discourse is quite puzzling. The question now: why does Japan persistently avoid dialoguing with North Korea? From a domestic perspective, a negative tone in Abe’s discourse about North Korea is needed to help promote his political agenda, while reigniting old differences as a buffer zone against any normalization of the Japanese-North Korean relations as well as expressing skepticism about any North-South Korea rapprochement. In other words, it is more convenient for the Abe administration to block the North Korean military growth, and capitalize instead in a strong Japan-US Alliance or South Korea-US Alliance. Abe remains hopeful there will no push for a North and South Korea reunification. Moreover, he is more skeptical about the feasibility of the ‘denuclearization’ process in the Peninsula.

The Two Parralels: ‘Inter-Korean’ Summit and ‘US-North Korea’ Summit!

It was a rare moment in history to witness the North and South Korean leaders interact in their summit in Panmunjom in 2018. It was the first meeting in a post-1953 Ceasefire era after the Korean War. A South Korean President steps on North Korean territory and a North Korean leader returns the gesture by walking together to South Korea in a security-tight demilitarized zone known as DMZ. After the Korean summit, the Panmunjom Declaration was well-received as a “historic event” by various governments and world opinion.

However, it echoed a different sentiment inside Japan. Almost all news programs in various Japanese media outlets assessed covered the summit randomly with no specifics or particular significance. Instead, they considered the statement to be rather ‘broad’, and did not address the Japanese concerns. The expectations in Tokyo were high and presumed the statement could have been “comprehensive”, including the ‘nuclear threat, missile launching and abduction’. (15)

Tsutomu Nishioka, a Japanese Korea policy expert, asserts the term “denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula” was not a new outcome. Current leader Kim Jong-un simply echoed the last words of his late father Kim Jong-il. It was a reoccurring theme in North Korea’s political rhetoric for generations. Nishioka argues it was the same old wine served in new glasses. The “denuclearized area of the Korean Peninsula” was initiated by Kim Jong-il in 1991 as a timely tactic to push the US forces out of the Penninsula. The core of this approach was an intended disorganization of the US-South Korea alliance. (16) According to the Panmunjom Declaration, “South and North Korea shared the view that the measures being initiated by North Korea are very meaningful and crucial for denuclearization of Korean Peninsula.”

While reflecting on the statement, Nishioka points out that the “measures being initiated by North Korea’ refer to a decision made at the Workers’ Party Central Committee’s general meeting on the 20th April to stop nuclear and missile tests and scrap the nuclear test field. However, this decision was made because ’the national nuclear forces have already been completed’ according to them. North Korea declared itself a nuclear power.”(17)

Another observer, former head of security for Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization (KEDO), Akihiro Kuroda, argues the cost of the denuclearization process, as President Trump expected to be paid not by the United States, but Japan and South Korea, will be enormous. Kuroda indicated the cost “would be several dozens of billion yen”, depending on the scale of developing North Korean nuclear capabilities. He also believes the best case scenario of commissioning all nuclear equipment and missiles would take ten years at least. (18)

A majority of American Korea specialists are confident that North Korea will never relinquish its nuclear power. (19) For instance, Young C. Kim, professor of Japan and Korea Politics at Georgetown University points out that Trump has gathered some of his hard-line men, namely National Security Adviser John Bolton and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, to push for full implementation of the denuclearization of the region. Shortly before the Inter-Korean Summit, he appointed Pacific Command Chief Harry B. Harris as the new US Ambassador to South Korea. As Dr. Kim argues, “Respective countries will regard this as an act of suggesting inclination prepared for the adoption of a military option. This is actually a turbulent era mixed with geopolitical strategic thoughts.”(20)

Similarly, Tokyo has more doubts about the effectiveness of any US-DPRK summit as it refers to past attempts of solving the conflict. In 1994, the United States reached the so-called ‘Agreed Framework’ accord with North Korea, and imported 500,000 tons of heavy oil, light-water reactor construction and food supplies in return for freezing North Korean nuclear development program. North Korea, however, defied the agreement. Nine years later, the six-party talks [United States, North Korea, South Korea, China, Russia, and Japan] were held with some optimism. At the fourth meeting held September 19, 2009, North Korea issued a joint statement on behalf of the summit and declared its approval of giving up its nuclear development activities. However, the agreement did not last for long.

The United States maintained pressure on North Korea while pursuing a “complete, verifiable and irreversible disarmament”, commonly referred to by its acronym “CVID.” Moreover, in terms of its methodology, Washington was considering applying the ‘Libya model’ of dismantling the nuclear equipment to the denuclearization process of North Korea, as US National Security Advisor John Bolton stated following the Panmunjom Declaration. (21) However two weeks later, there was some irony inside the White House as President Trump denied “the Libya model isn’t a model we have at all.” (22)

North Korea reacted with harsh words, and threatened with the possibility of canceling the Trump-Kim summit. It also criticized Vice President Mike Pence as “ignorant and stupid”, and waved the nightmarish scenario of a “nuclear war.” (23) Still, these differences did not block the US-North Korea summit which led to a joint agreement to start the denuclearization process of Korea. Although Pyongyang promised “complete denuclearization” in the joint statement, there have been no “verifiable” and “irreversible disarmament” words, despite Washington’s high expectations.

Still, the United States and Japan insist that CVID and the Libya model are crucial for any North Korean denuclearization since North Korea have ignored past agreements time and time again. Therefore, the focal point of any future Trump-Kim summit agenda should pivot around these specific methodologies for denuclearization.

North Korea Denuclearization: Reality or lllusion?

One major challenge is the ambiguity of CVID and how it should be implemented. Some observers like Kan Kimura at Kobe University argues CVID is out of the scope of execution in the case of North Korea although it looked promising in the case of Libya. The Qaddafi regime advanced its nuclear program from the 1980s; but, ended up canceling it as a compromise with Bush administration in order to secure its survival. The International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA) inspectors proceeded with their verification mission inside Libya. According to Kimura, the Agency concluded the implementation of denuclearization was “complete, verifiable, and irreversible disarmament.” (24)

Libya’s decision was welcomed by the international community. As a result, sanctions were lifted off. However when the civil war broke out in the country in 2011, several Western nations pushed together for the defeat of the Qaddafi regime. The United Kingdom, France and the United States intervened military under the flag of ‘Responsibility to Protect’ (R2P). (25) Kimura argues, “The Libyan lesson means that although the Qaddafi regime showed its commitment to giving up its nuclear program, the international community did not consider such commitment. Unless North Koreans have enough trust the Libyan scenario will not repeat itself again, they will easily consider getting rid off any nuclear weapons.” (26)

North Korea’s nuclear capabilities are far more advanced than Libyan program, and it is easy to transport individual nuclear weapons as well as enriched uranium and plutonium. If certain quantities of these materials are secured, it is not difficult to build nuclear weapons again. As various nuclear dismantlement activities will be carried out under North Korean sovereignty, those activities have limitations; therefore the denuclearization process will mostly be “incomplete, unverifiable, and reversible.”(27) Now, the international community still insists on having North Korea report details of its nuclear weapons and plutonium. However, Pyongyang has never admitted it has enriched uranium. If North Korea maintains the same argument, the hope in holding a Trump-Kim denuclearization deal will come to a halt. (28)

The White House strongly insists on one particular condition: North Korea must accept CVID while planning the Trump-Kim summit. It pursues Pyongyang would commit to a “complete, verifiable, and irreversible security arrangement” (CVISA) to be verified by the United States. (29) In contrast, North Korea’s demands are clear: the CVISA would mean Washington will have to give guarantees for the safeguard of the Kim’s regime in return for giving up nuclear weapons. The Kim regime perceives the disarmament of the peninsula as a winning card in the diplomatic game with the White House. North Korean leader would never accept nuclear disarmament unless Kim Jong-un’s regime’s longevity is guaranteed by the United States and others. (30)

However, South Korea has some concerns regarding the regime guarantees, where the stigma of dictatorship remains dominant. Japanese observer Katsuhiro Kuroda points out that Kim Jong-un has eliminated his brother as well as his uncle by assassination. However, Kuroda argues there is a clear double standard policy in the South Korean current position toward the future of the Kim regime. “There has a growing trend of appeasement in Seoul’s policy coming from the Moon progressive administration’s rapprochement,” as Kuroda asserts, as it “may contradicts their advocacy of human rights and democracy while expressing some political allergy to dictatorship.” (31)

Denuclearization Deal between Two ‘Rocket Men’

In the 2017 UN General Assembly in New York, Trump lambasted Kim as “Rocket Man”, and pushed for an alarming standoff between Washington and Pyongyang. He also threatened with the use of force in containing the North Korean nuclear aspirations, “The United States has great strength and patience, but if it is forced to defend itself or its allies, we will have no choice but to totally destroy North Korea. Rocket Man is on a suicide mission for himself and for his regime.”(32) Ironically, The characterization of ‘Rocket Man’ Kim has shifted to a “very talented man” in 2018. (33)

According to the “Fear: Trump in the White House” book by investigative journalist Bob Woodward, Trump was subjected to growing pressure by members of his administration not to take Kim’s promises too seriously. His advisors seem to have stopped him from publicizing a tweet draft about a possible escalation in the Korea Penninsula, “We are going to pull our dependents from South Korea – family members of the 28,000 people there.” If tweeted, this call for emergency measures could be interpreted by North Koreans as ‘an imminent US attack”. (34) Ironically, the subtle option of using force in the standoff implies possible confrontantiona similarities between ‘Rocket Man Kim’ as well as ‘Rocket Man Trump’!

Since the beginning of 2018, Trump has changed his hostile tone toward North Korea. (35) Pyongyang has expressed the intention of initiating the denuclearization process. President Moon has reinforced his neighbor Kim’s promises of “getting rid of everything, including all of the North’s current nuclear weapons and nuclear materials.” (36)

Despite this optimistic view, one of the remaining challenges of the US-DPRK denuclearization deal is how to walk on the fine line between three major expectations: 1) implementation of the denuclearization deal; 2) Washington’s demands of the CVID requirements; and 3) the provision of CVISA for Kim’s regime. As the United States and North Korea have pledged in the post-summit joint statement, “President Trump is committed to providing security guarantees to the DPRK, and Chairman Kim-Jong Un reaffirmed his firm and unwavering commitment to complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.” (37) This particular statement highlights the fact that President Trump provides “security guarantees to the DPRK, not to the Kim Jong Un regime.”

North Korea has demanded complete denuclearization of “the entire Korean Peninsula.” This request includes the abolishment of nuclear weapons of the US military forces stationed in South Korea. The Seoul-Pyongyang Agreement calls for armament reduction as well as scaling back the US military presence in the Korean Peninsula. If the Korean Peninsula is expected to be completely denuclearized, this shift would imply less significance of the would-be shrinking US forces in the region, which will raise Japan’s concerns vis-à-vis possible North Korean threats in the future.

When the United States and South Korea canceled their plans for holding joint military exercises in June 2018, Japan’s Foreign Minister Taro Kono welcomed the decision whereas his colleague Defense Minister Itsunori Onodera raised concerns over what he considered and ‘decreasing’ deterrence of the Kim regime. In his news conference in Tokyo, Mr. Onodera stated, “The US military deterrent forces, including those depployed in South Korea, are indispensable for peace and stability in the Asia-Pacific Region.”(38)

As a result, any pursuit of North Korean denuclearization process will be controlled by three fundamental challenges: 1) CVID has enormous technical and financial difficulties; 2) there is sharp contrast between CVID and CVISA in the individual assessment of each capital: Washington, Pyongyang, and Seoul; and 3) the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula may lead to reduction in US geopolitical and military presence. China and Russia remain keen on benefiting from any strategic change on the ground.

In Seoul, President Moon made a significant promise on behalf of his neighbor Kim; “North Korea is prepared to invite experts who will inspect military reduction in major plural missile bases as well as the closure of the major nuclear test site in Yongbyon.” (39) This pledge may sound very promising; however, it remains unclear whether it will evolve into the CVID. Still, Seoul and Pyongyang have made a leap forward the normalization of their diplomatic ties. However, there is significant opposition in Tokyo.

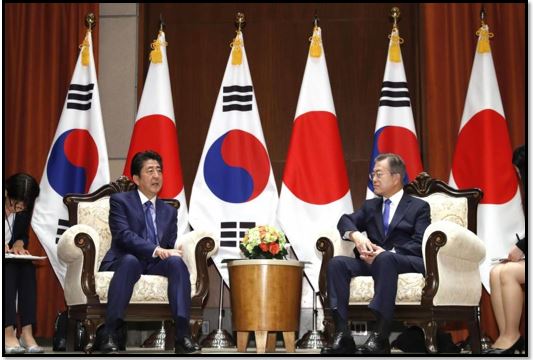

During the Japan-South Korea summit held in New York September 25, 2018, President Moon explained to Japanese Prime Minister Abe that the Kim Jong-un, who also has the title of ‘Chairman of the Workers’ Party of Korea’, should “hold a face-to-face meeting with Mr. Abe and discuss the abduction issue.” (40) Moon also said,“we are prepared to hold talks with Japan at the appropriate time with the aim of improving regional relations.”(41) President Moon also suggested to Mr. Abe “the environment is not yet ready. Japan should consider a constructive environment for the denuclearization project to go forward. (42) He also believes “the normalization of the North Korea-Japan relations is required in the process of reaching peace in the Korean peninsula. I will support this and extend my cooperation to hold a North Korea-Japan summit.” (43)

Moreover, Mr. Abe was quoted saying, “I am prepared to meet directly with Kim Jong-un, breaking the shell of mutual distrust held with North Korea.”(44) According to other sources, he argued for “maintaining sanctions in order to draw out meaningful actions from North Korea for denuclearization.”(45) These two statements seem to have different trajectories. Abe may have implied he has no intention of responding to Pyongyang and will continue his support international sanctions on his neighbors.

On an ironic note at this summit, Mr. Abe urged Mr. Moon not to bring to the fore any discussion of two sensitve issues: 1) the so-called “comfort women” controversy (i.e. sex-slavery rings.) This is a lingering postwar reparation issue concerning a number of Korean women, who were forced into sexual slavery in Japanese brothels during World War II. 2) the “requisition” issues as a reference to forced labor among about 700000 Korean workers who were ‘exploited’ by the Japanese government and companies during the same era. (46)

In 2015, Japan and South Korea reached an agreement, known as the “Irreversible Solution”, which called for ending bilateral talks about this kind of post-World War II reparation issues. Three years later, conservative politicians and other interlocutors still argue about those issues as a chosen trauma commemoration. The ‘comfort women’ issue remains one of the biggest obstacles for the Japan-South Korea detente. (47)

In his 2017 National Liberation anniversary speech, President Moon stated “If Inter-Korean relations are improved, the government would explore the possibility for a South-North joint fact-finding survey on the damage of forced mobilization.” (48) As for the future, one conservative observer in Tokyo predicts an interesting scenario: “If we suppose the abduction issue ? one of the most important issues for Japan ? is solved, the government will move forward toward diplomatic normalization with North Korea. Pyongyang will probably demand Japan for postwar reparations including ‘comfort women’ and ‘requisition’. Then, South Korea may get involved in these negotiations.” (49)

|

| [Kyodo] |

Conclusion: Non-Nuclear Korea or Trump-Kim Theatrics?

Despite its symbolic and media-driven interest in the upcoming Trump-Kim summit, the potential US-DPRK denuclearization project has a slim chance of implementation. The emerging appeasement strategy between Seoul and Pyongyang may lead to some escalate certain issues in the Tokyo position. Japan has drifted into a rather isolated position as a result of the Moon-Kim political convergence.

If Japan’s Prime Minister Abe steers the country toward dialogue with Mr. Kim, this shift may undermine the rationale for constitutional amendment and military growth. Any level of the desired denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula will also lower the US military role in the region. This solidifies Japan’s concerns about national security and protection.

Although the denuclearization agreement between Washington and Pyongyang have to face major difficulties, one can argue the whole deal will represent no more than political theatrics of the two leaders in Washington and Pyounyang. Jeffrey Lewis, an expert in nuclear non-proliferation systems, has done a simulation of the US-DPRK nuclear conflict in his “The 2020 Commission Report on the North Korean Nuclear Attacks Against the United States”. (50) He formulated a nuclear war scenario in detail by starting a North Korea attack on a civil aviation in South Korea after the failure of the second round of the denuclearization talks. A tit-for-tat escalation is expected by South Korea, and ultimetaly United States and Japan. Lewis also foresees a possible scenario of 1.4 million casualties should North Korean nuclear missiles reach Japan and South Korea, as well as 1.4 million fatalities and injuries from ICBMs targeting the United States.

If the Trump-Kim denuclearization talks come to a deadlock in the future, Lewis’s nightmarish scenario may become real. The complexity grows deeper when one takes into consideration the following political mis-matches: a) confrontation between a Japanese-US alliance against North Korea, b) reconciliation between South Korea and North Korea, c) Japan’s call for North Korea sanctions will a counter force against the previous ouvertures in the US-North Korea and South Korea NorthKorea relations.

(1) Al Jazeera (2018), ‘2nd Trump-Kim summit early next year, US President says’, 8 November, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/11/2nd-trump-kim-summit-early-year-president-181108054133882.html (Accessed 15 November)

(2) Tom Balmforth, et al. (2018), ‘Moscow speaks of need for five-way international talks to end Korean tensions’, Reuters, 10 October, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-northkorea-nuclear-russia/moscow-speaks-of-need-for-five-way-international-talks-to-end-korean-tensions-idUSKCN1MK0PI (Accessed 14 October 2018)

(3) Note that Kim Jong-un had several times of summit with China’s Xi Jinping in Beijing before and after the inter-Korean summit and US-North Korea summit.

(4) Naoto Yamagishi (Producer), Hiromi Kamoshita (Director) (11 May 2018), PRIME News Evening [Television broadcast], Tokyo: Fuji Television Network. Cf. https://www.fnn.jp/posts/00310040HDK

(5) Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan (2018), ‘Japan-ROK Summit Meeting’, Issued on 7 September, https://www.mofa.go.jp/a_o/na/kr/page3e_000760.html (Accessed 20 November)

(6) North Korea claims that eight of the twelve abductees are already dead or disappeared

(7) Under administration of the Democratic Party of Japan [2009 and 2012], the government has been propounding the ‘Northeast Asia Denuclearization flamework’ together with South Korea and North Korea under the concept of ‘fraternity politics’.

(8) See, UN Documents, S/RES/1965, 15 July 2006; S/RES/1718, 14 October 2006; S/RES/1874, 12 June 2009; S/RES/1887, 24 September 2009; S/RES/1928, 7 June 2010; S/RES/1985, 10 June 2011; S/RES/2050, 12 June 2012; S/RES/2087, 22 January 2013; S/RES/2094, 7 March 2013; S/RES/2141, 5 March 2014; S/RES/2207, 4 March 2015; S/RES/2270, 2 March 2016; S/RES/2276, 24 March 2016; S/RES/2321, 30 November 2016; S/RES/2345, 23 March 2017; S/RES/2356, 2 June 2017; S/RES/2371, 5 August 2017; S/RES/2375, 11 September 2017; S/RES/2397, 22 December 2017; S/RES/2407, 21 March 2018.

(9) BBC News (2017), ‘North Korea fires missile over Japan in ‘unprecedented threat’, 29 August, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-41078187 (Accessed 24 October)

(10) Claire Phipps and Graham Russell (2018), ‘North Korea: ballistic missile launched over Japan – as it happened’, The Guardian, 15 September, https://www.theguardian.com/world/live/2017/sep/15/north-korea-launches-missile-over-japan-live-updates (Accessed 25 October)

(11) E.g. Shigeru Ishiba (2017), ‘Improving a deterrent force? [in Japanese]’, Blog post, 15 September, Retrieved from http://blogos.com/article/246468/

(12) Alexandra Ma (2018), ‘Kim Jong Un joked that he’d no longer ‘interrupt’ the South Korean president’s sleep with early-morning missile tests’, Business Insider, 27 April, https://www.businessinsider.com/korea-summit-kim-jong-un-jokes-with-moon-jae-in-about-missile-tests-2018-4 (Accessed 30 October)

(13) Raymond Lee (2018), ‘A Trump-Kim Summit: Hyper Rapprochement or Marginalization of China?’, Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, 1 May, http://studies.aljazeera.net/mritems/Documents/2018/5/1/a0944426788a4f8d8e5c6d5cfc8b1f2f_100.pdf

(14) Reuters (2018), ‘It must tend to solve the abduction issue: PM Abe on Japan-North Korea summit’ [in Japanese], 18 June, https://jp.reuters.com/article/abe-north-korea-meeting-idJPKBN1JE0A9 (Accessed 18 October)

(15) Jun Sakurada (2018), ‘Avoid ‘Deterioration’ Produced by Unifying North Korea’ [in Japanese], Sankei Shinbun, 4 May, https://www.sankei.com/column/news/180504/clm1805040005-n1.html (Accessed 14 October)

(16) Tsutomu Nishioka (2018), ‘Banmunjom Declaration without Human Rights and Nuclear Abolition [in Japanese]’, Sankei Shinbun, 2 May, https://www.sankei.com/column/news/180502/clm1805020004-n1.html (Accessed 16 October 2018)

(18) Akihiro Kuroda (2018), ‘North Korea’s Denuclearization Became “Hard Going” from the Beginning? [in Japanese]’, Zero-tele News24, 13 June, http://www.news24.jp/articles/2018/06/13/10395812.html (Accessed 18 October)

(19) Sankei Shinbun (2018), ‘US Keep Watch on “Dialogue=Accepting Nuclear-Nation”, “Master Card” For Trump: US Professor Emeritus Young C. Kim’ [in Japanese], 3 May, https://www.sankei.com/world/news/180503/wor1805030009-n1.html (Accessed 14 October 2018)

(21) Joshua Berlinger (2018), ‘Bolton says US considering Libya model for North Korean denuclearization’, CNN, 30 April, https://edition.cnn.com/2018/04/30/asia/north-korea-bolton-libya-intl/index.html (Accessed 16 October 2018)

(22) Rick Noack (2018), ‘Trump just contradicted Bolton on North Korea. What’s the ‘Libya Model’ they disagree on?’, The Washington Post, 17 May, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/world/wp/2018/05/16/whats-this-libya-model-north-korea-is-so-angry-about/ (Accessed 16 October)

(23) BBC News (2018), ‘North Korea says US Vice-President Pence’s comments ‘stupid’’, BBC, 24 May, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-44234268 (Accessed 26 October)

(24) Kan Kimura (2018), ‘Not Easy “Complete Denuclearization”: A Sign of Shift of the US Involvement in Korean Peninsula’[in Japanese], Nippon.com, 22 June, https://www.nippon.com/ja/in-depth/a05901/ (Accessed 14 October 2018)

(25) See, UN document, S/RES/1970, 26 February 2011; S/RES/1973, 17 March 2011.

(30) Uri Friedman (2018), ‘The ‘Compliment Trump’ Doctrine’, The Atlantic, 26 September, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/09/north-south-korea-moon/571321/ (Accessed 21 October)

(31) Katsuhiro Kuroda (2018), ‘Moon administration’s Handling and Major Contradiction [in Japanese]’, Sankei Shinbun, 8 May, https://www.sankei.com/world/news/180508/wor1805080029-n2.html (Accessed 14 October)

(32) Donald Trump (2017), ‘Remarks by President Trump to the 72nd Session of the United Nations General Assembly’, The White House, September 19, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-72nd-session-united-nations-general-assembly/ (Accessed 21 November 2018)

(33) Jacob Pramuk (2018), ‘North Korean starvation and killings? Trump says Kim Jong Un is ‘very talented’ but not ‘nice’’, CNBC, 12 June, https://www.cnbc.com/2018/06/12/trump-heaps-praise-on-kim-jong-un-during-nuclear-weapons-summit.html (Accessed 22 October)

(34) Rosie Perper (2018), ‘Bob Woodward said Trump nearly provoked North Korea into war with a single tweet’, Business Insider, 9 September, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/sep/10/trump-almost-sent-tweet-north-korea-imminent-attack (Accessed 22 October); cf, Bob Woodward, Fear: Trump in the White House, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018.

(35) However, North Korea may be restart nuclear development if the US did not lift economic sanction, according to Bruce Klinger, a former CIA deputy division chief for Korea. Despite saying “I would love to take the sanctions off,” Trump “is insistent on holding the full pressure campaign untuil he gets the full denuclearization.” On the contrary, North Korea is “getting really angry.” Cf. Nicole Gaouette, Michel Kosinski and Barbara Starr (2018), ‘North Korea ‘really angry’ at US as tensions rise’, CNN, 8 November, https://edition.cnn.com/2018/11/07/politics/north-korea-trump-pompeo-tensions/index.html(Accessed 5 November)

(36) Seong Yeon-cheol (2018), ‘Moon says Kim Jong-un is willing to get rid of everything in nuclear program’ [in Japanese], Hankyoreh, 13 October, http://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_northkorea/865677.html (Accessed 18 October).

(37) The White House (2018), ‘Joint Statement of President Donald J. Trump of the United States of America and Chairman Kim Jong Un of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea at the Singapore Summit’, Issued on 12 June, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/joint-statement-president-donald-j-trump-united-states-america-chairman-kim-jong-un-democratic-peoples-republic-korea-singapore-summit/ (Accessed 23 October)

(38) Sankei Shinbun (2018), ‘Canceled US-South Korea Military Exercise: Arise Concern that its Decline of Deterrence among Japanese Government, Ministry of Defense says ”Unwished Surprise” [in Japanese]’, 19 June, https://www.sankei.com/world/news/180619/wor1806190032-n1.html (Accessed 18 October)

(39) Nick Macfie (2018), ‘South Korea’s Moon says North Korea means to abolish all nuclear weapons’, New York Times, 12 October, https://www.nytimes.com/reuters/2018/10/12/world/asia/12reuters-northkorea-nuclear.html (Accessed 18 October)

(40) Makiko Tanaka (2018), ‘Mr. Kim Jong-un “Face up to PM Shinzo Abe”: Korea’s President Moon Jae-in reveal, Japanese government analyzes carefully’ [in Japanese], Sankei Shinbun, 26 September, https://www.sankei.com/politics/news/180926/plt1809260021-n1.html (Accessed 23 October)

(41) Kotaro Ono and Yoshihiro Makino (2018), ‘Seoul says Kim Jong Un in no rush for summit talks with Japan’, The Asahi Shinbun, 26 September, http://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/AJ201809260030.html (Accessed 23 October)

(43) Justin McCurry (2018),‘’Break the shell of mistrust’: Shinzo Abe willing to meet Kim Jong-un at summit’, The Guardian, 26 September, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/sep/26/break-the-shell-of-mistrust-shinzo-abe-willing-to-meet-kim-jong-un-at-summit (Accessed 23 October)

(44) Kotaro Ono and Yoshihiro Makino, op.cit.

(46) The Republic of Korea Cheong Wa Dae (2018), ‘The President and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe Hold Summit’, 25 September, https://english1.president.go.kr/BriefingSpeeches/Briefings/329.

(47) Note that the supreme court of South Korea adjudicated a Japanese major steelmaker company should compensate of 100 million won to each of the four South Koreans plaintiffs for forced labor during the Japan’s colonial rule between 1941 and 1943. This judge engendered myriad of controversy in Japan. Respecting the adjudication, Japanese government and the company concerned called the decision “very regrettable and totally unacceptable,” Prime Minister Abe told with a caustic tone that “the ruling this time is impossible in light of international law,” Japanese Foreign Minister Kono alluded to take the case to the International Court of Justice. Whereas President Moon on this ruling had no immediate reaction. But this ruling is difficult to oppose for the President, who once represented South Korean laborers as a layer in the 2000s. The requisition issue causes and galvanizes the friction between the nations and might be an obstacle for the future cooperation of the denuclearization process.

(48) Ministry of Foregin Affairs Republic of Korea (2018), ‘Address by President Moon Jae-in on the 72nd Anniversary of Liberation’, Issued on 16 August, http://www.mofa.go.kr/eng/brd/m_5475/view.do?seq=318949&srchFr=&srchTo=&srchWord=&srchTp=&multi_itm_seq=0&itm_seq_1=0&itm_seq_2=0&company_cd=&company_nm=&page=5&titleNm= (Accessed 23 October)

(49) Sankei Shinbun (2018), ‘[History Wars] Japanese Government Exercise Caution Bipartisan Coalition of Unified Korea, On National Joint Event in ‘Panmunjom Declaration’, Reignite the Issue of Comfort Woman and Requisitioned Civilians?’ [in Japanese], 6 May, https://www.sankei.com/politics/news/180506/plt1805060005-n2.html (Accessed 16 October).

(50) Jeffrey Lewis (2018), The 2020 Commission Report on the North Korean Nuclear Attacks Against the United States: A Speculative Novel, London: WH Alen..