After a three-month-long stalemate of the US-Taliban negotiations, President Donald Trump made an unannounced visit to Afghanistan to celebrate Thanksgiving with US troops in Bagram airbase, alongside Afghan president Ashraf Ghani, November 28, 29019. Trump told reporters that Taliban “wants to make a deal” and that US officials were “meeting with them”. One week earlier, Washington and Talban reached a prisoner-swap agreement to free three Taliban commanders, in exchange for two western university professors, American Kevin King and Australian Timothy John Weeks, taken hostage three years ago. (1) This shift was considered a ‘confidence-building measure’ three months after Trump halted the Qatari-brokered peace talks, and accused Taliban of seeking “false leverage”. After the visit, Trump sounded optimistic about his ceasefire condition; “We’re saying it has to be a ceasefire, and they didn’t want to do a ceasefire… Now they do want to do a ceasefire. I believe it’ll probably work out that way.” However, Taliban maintained it was “way too early” to speak of resuming direct talks.

By mid-November, there were conflicting reports about the whereabouts of the three prisoners. A Taliban spokesperson states they had not left the prison, and blamed the U.S. for the failure of the swap. In early December, U.S. Defense Secretary Mark Esper told Reuters any future troop drawdowns in Afghanistan were “not necessarily” linked to a deal with Taliban. This decision may pave the way for reducing the 13,000 U.S. forces in Afghanistan to 8,600 with the hope they would still carry out an “effective, core counter-terrorism mission.” (2) NATO troops are expected to shrink in numbers in Afghanistan as well. In this paper, Nilofar Sakhi, Fulbright scholar and a visiting fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy, Columbia University, and International Center for Tolerance Education examines the dynamics and strategies of negotiations between the United States and Taliban. She also assesses the accumulative impact of nine rounds of peace talks. This paper builds up on her previous analysis “Peacemaking in Afghanistan: Procedural and Substantive Challenges” published in May 2019. It can accessed through: http://studies.aljazeera.net/en/reports/2019/05/peacemaking-afghanistan-procedural-substantive-challenges-190508101859579.html

|

| Trump serves Thanksgiving dinner to troops at the Bagram airbase near Kabul [Getty] |

The peace talks initiated between the United States and Taliban in Doha, Qatar in 2018 spurred optimism throughout Afghanistan. Further talks then took place in Moscow between Afghan political elites and Taliban. These talks, however, have largely lacked strategic direction. The nine rounds of negotiations between the United States and Taliban were initially organized and consistent. These talks were initiated around four key elements: assurances around counterterrorism (a global concern); the withdrawal of foreign troops (a Taliban concern); and intra-Afghan negotiations, including an agreement on a roadmap for the political future of Afghanistan, and comprehensive ceasefire.

Conceptual Framework for Political Negotiations

Political negotiations are often messy, slow, and gradual processes. In addition to developing an acceptable agreement to meet the interests of both parties, issues must be framed and reframed, hostilities reduced, and changes in the parties’ perception and understanding of the conflict must take place. The process requires procedural arrangements that include the organization and structure of the negotiation process, and substantive content-based preparation.

The bargaining styles of the parties and the way in which the negotiations are framed also have an impact on the outcome. Therefore, both political issues and the skills of negotiators often determine the success or the failure of the talks. Political negotiations should be based on the fundamentals of “deliberative negotiations,” which rest on each party exploring all possible needs and interests of the other, but also seeking fair compromises. Such processes include long-term interactions, incentives, and a level of secrecy until a deal is signed.

The nine rounds of negotiation between Taliban and the United States were, in several ways, a deliberative negotiation. First, the talks were closed and the content of the discussions kept secret. Second, the talks were in-depth and contained some confidence building measures, inclusive of long-term engagement and releasing Taliban detainees held by the government of Afghanistan. However, long-term engagement was not sufficient to build the necessary trust and confidence between the parties, due to profound contradictions in their respective values and perceptions, as well as contradictory messages from both parties. Moreover, the lead negotiator, Special Envoy Zalmai Khalilzad, downplayed the radical nature of Taliban in naming them a “traditional orthodox Islamic group.” Rather than facilitate relationship building between the parties and reduce hostilities, this strategy was counterproductive. Taliban used this opportunity to demand more from the US and the talks more generally.

|

| Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, the Taliban group's top political leader, third from left, arrives with other members of the Taliban delegation for talks in Moscow, Russia. May 28, 2019 [Getty] |

The rushed and abrupt messages coming from the US government on the subject of US military withdrawal also hardened the path to negotiation and, particularly the bargaining stance of Taliban. Perceiving the United States may withdraw from Afghanistan with little notice, Taliban questioned why they should even negotiate in the first place. As such, rather than weakening Taliban’s negotiating position, it further strengthened it. Taliban further illustrated their power and strength by escalating violence throughout the country. Before the collapse of the talks in September 2019, their last attack was the bombing of a secure compound for foreign contractors and visitors on the outskirts of Kabul.

At the time, Taliban spokesperson said they were targeting “foreign occupiers.” In reality, however, most of the 16 people killed were Afghan civilians. This attack became one of the reasons for the collapse of the talks. Rather than demonstrating a willingness to come to the negotiation table, Taliban demonstrated a complete disinterest in changing their attitude and behavior, which will be needed to facilitate a sustainable peace deal.

Negotiation Styles

It is not easy to probe into the negotiating styles of both parties as the discussions remained closed throughout and the representatives of both sides were neither authorized to discuss the details of the negotiations nor the interactions between the parties. The following analysis of the role of each of the parties as negotiators and the effectiveness of their negotiation styles is based on the outcome of nine rounds of talks.

1. Taliban

Taliban remained focused on their initial negotiating stance throughout the entire process. They demonstrated positioning bargaining by opposing the inclusion of the Afghan government. They also remained committed to their fundamental beliefs around foreign intervention by standing firm on their condition of US military withdrawal as the foremost condition to bring about a cease-fire and any intra Afghan peace talks. As such, the nine rounds of negotiation did not bring about any change in their initial bargaining position.

These rounds of negotiation did not change their vision for a post-war Afghanistan, which derives from an Islamic legal system, ensuring women’s rights “within the Islamic framework of Islamic value.” Taliban have never laid out in detail what they mean by Islamic values. Yet, looking to the recent past to when Taliban ruled Afghanistan (1996-2001), there is little doubt they may seek to re-implement their former system of governance based on their own interpretation of Islamic values that set Afghanistan back socio-economically.

2. Zalmai Khalilzad

The appointment of Special Envoy, Zalmai Khalilzad, as lead negotiator has been both positive, on one hand, and less positive, on the other. His position as an Afghan-American diplomat and former US Ambassador to Afghanistan (2003-2005) has equipped him with a deep understanding of Afghan political history, culture, and religion, and contemporary regional politics, inclusive of relational dynamics among all the parties to the conflict. Taken together, they have provided him with the recognition and respect of the relevant parties. Conversely, as an envoy, Zalmai Khalilzad has lacked neutrality and impartiality.

Khalilzad has become a party to the conflict with clear interests and objectives. More specifically, he played the role of viceroy whereby he took over command from his superiors of the procedural arrangements for the negotiations and framing and reframing the issues. In such circumstances, he was bound by certain diplomatic procedures, which somewhat prevented him from playing the role of skilled negotiator in bringing the parties together and leading them to a comprehensive settlement.

Khalilzad demonstrated a participatory and compromising negotiation style. He toured Kabul and the region, meeting all the powerbrokers and parties with interests in peace and conflict in Afghanistan. Khalilzad was not only capable of reaching political parties, elites, Taliban, and representative from regional countries, but also civil society groups, women’s groups, religious leaders, and youth. Moreover, he has been using appreciative inquiry to engage Afghan polity and create optimism about the future of Afghanistan. This approach adopted by Khalilzad was brought to the fore in his tweets, whereby he provided updates and encouraged actors to finding common ground.

In one of his tweets following the intra-Afghan peace dialogue in Doha, Khalilzad said ‘I congratulate the participants-Afghan society representatives across generations, senior government officials-for finding common ground,” These messages had meaningful impact symbolically on participants and the process. Despite his ability to reach out to a variety of powerbrokers, his relationship with Afghan President, President Ghani, was cold throughout the first year of talks due to President Ghani’s insistence that his government be instrumental in the peace process, lead any negotiations with Taliban. Taliban, however, refused any notion of the Afghan government having a leading role in the talks.

Overall, Khalilzad’s participatory and compromising negotiating style was strength to the process. This approach made an insurgent group organize and frame their interests and demands, and the process took on a formal structure. Before the talks collapsed in September 2019, nine rounds of formal negotiation were unprecedented. With that said, Khalilzad was unable to convince Taliban to change their perception toward the Afghan government. Further, Khalilzad’s diplomatic relations with regional countries and, particularly Pakistan were unable to produce tangible results in the form of support for peace and stability in Afghanistan. However there have been verbal commitments to a peace process, no practical and formal steps have been taken to consider a regional agreement on peace in Afghanistan that addresses the interests and needs of key powerbrokers.

|

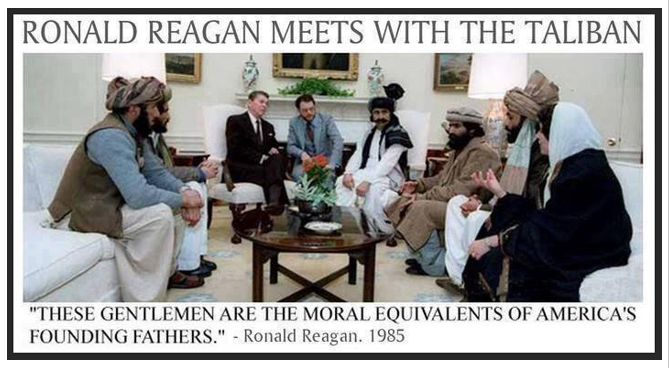

| Taliban at the White House 1985 [Unspecifeid] |

The Impact of Nine Rounds of Peace Negotiations

The peace talks initiated between the United States and Taliban in Doha, Qatar in 2018 spurred optimism throughout Afghanistan. Further talks then took place in Moscow between Afghan political elites and Taliban. Plans are now being made to start intra-Afghan peace talks in Beijing. These talks, however, have largely lacked strategic direction. That said, the nine rounds of negotiations between the United States and Taliban were initially organized and consistent. These talks were initiated around four key elements: assurances around counterterrorism (a global concern); the withdrawal of foreign troops (a Taliban concern); and intra-Afghan negotiations, including an agreement on a roadmap for the political future of Afghanistan, and comprehensive ceasefire.

Though the process created a sense of hope and optimism among the Afghan people, this optimism was accompanied by skepticism. Skepticism about the outcome of the process was compounded by the escalation in violence throughout the country at the time of the talks and the lack of any signal from Taliban of their intention to constructively work toward a peace deal.

Current efforts toward peace have also created two prominent (and negative) narratives that ultimately created hurdles to the advancement of the process. First, Taliban are being reframed as a traditionally conservative religious group rather than a terrorist organization. This reframing of the image of Taliban has been projected globally and, particularly to the American people. The consequences of this reframing are twofold. Not only has this reframing empowered Taliban, but enabled them to gain more leverage during the negotiation process. Second, current Afghan political leadership, faced with divided political factions within Afghanistan, were unable to create a coherent message, symbolizing unity for peace.

These factors further strengthened Taliban and their leverage at the negotiation table. If the Afghan government had been successful in bridging their differences with other political factions to create a united message, this could have prevented Taliban from continuing and spreading their military offenses. Viewing the government in conflict political and as militarily weak, Taliban used this to their advantage. As such, the intra-Afghan peace talks were problematic and controversial from their inception. Nevertheless, the US Special Envoy, Zalmai Khalilzad, managed to negotiate a peace deal. This deal, however, relied mostly on promises made by Taliban.

These promises included denying space to international terrorists on Afghan soil. Although the proposed deal remained secret, a meeting of Zalmai Khalilzad and President Ghani after the nine rounds of negotiation highlighted the broad issues regarding US troops withdrawal. Conflicting statements in Washington on the proposed deal negotiated in secret saw President Trump stress the urgency of removing US forces from Afghanistan and a key Republican senator and a group of US diplomats warn against a hasty withdrawal. Diplomats in Washington perceived civil war to be just around the corner for Afghanistan were a stronger deal not signed before withdrawal. With that said, Khalilzad and Taliban remained positive about getting a peace deal until the end of the nine rounds. Referring to the meetings between Khalilzad, the Qatari Foreign Minister and U.S. Army Gen. Austin Miller, Taliban spokesperson, Suhail Shaheen, tweeted, “both meetings were positive and well attended.”

In Afghanistan, momentum had gathered behind these talks and hope for an end to the years of atrocities and human suffering spread. More specifically, the peace talks between Taliban and the United States initiated a nonviolent peace movement facilitated through grassroots protests, youth peace walks, peace education activities conducted by universities and grass-root and civil society organizations working on peace and reconciliation, and through media outreach throughout the country. Though these activities were less coordinated at the provincial level, this movement could have generated cohesion through the participation of a broad spectrum of the Afghan population.

The diversity of those included in these activities and the peace movement more generally would have served to strengthen the movement over the long term. Moreover, these initiatives could have led to relationship building, which is a major pillar of a comprehensive framework for reconciliation. Further, engaging a group such as Taliban requires cosmopolitan conflict resolution where local actors connect with regional and international actors to contribute resources and expertise to find a solution.

The Collapse of the Talks

Unfortunately, the collapse of the talks has weakened momentum among the population, dashing hopes among the Afghan people about the possibility to ever living in peace. More generally, people have also lost trust in the process, believing Afghanistan will never benefit from such peace. This loss of trust was compounded by the lack of any obvious changes in the security situation throughout the country during the stalled peace process.

The fact the process neither guaranteed nor enforced any ceasefire, but rather saw an increase in the military actions of all parties generated further frustration and indifference among the Afghan people. Additionally, a majority of the population still have hidden grievances from Taliban era. Not only have these grievances yet to be addressed, this majority do not want members of Taliban to occupy any leading political posts in the future. For Afghans, Taliban are not a conservative religious group, but rather a terrorist organization with links around the world.

The abrupt collapse was shocking for everyone, including the Afghan government, the state of Pakistan, and the people of Afghanistan. From a peacemaking perspective, however, the collapse of the talks was an expected event. The peace process strengthened Taliban, granting them more leverage. As such, rather than seeking to negotiate a mutually beneficial endpoint, Taliban were rigid in their positions. For some political elites and the government of Afghanistan, the collapse was a success for the perspective of their negotiating position.

For them, not only did they lack trust in the process, they believe the key to peace in Afghanistan exists in Pakistan. There were also views about the origins and roots of Afghan conflict, which most believe depend on strategic diplomacy and pressure on Pakistan, as a state harboring and financing Taliban. Ultimately, for some political elites, they believe a military solution is the only viable option to defeat Taliban and reduce insurgency.

|

| US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo calling the Talban talks "Increadibly complicated" [Reuters] |

The United States expected Pakistan be a major facilitator and contributor to current peace talks in Afghanistan based on Prime Minister Imran Khan’s reassurances during his visit to the White House in July 2019. In return, Pakistan expected Washington to help with its domestic political and economic crises. Additionally, given recent developments concerning Pakistan’s status in the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), it is common belief Pakistan would benefit from any peace deal with Taliban. Any benefits would be mostly temporary. It is also important to consider the proxy war between Pakistan and India in Afghanistan.

Pakistan wants a weak Afghanistan in order to safeguard its widespread political influence, prevent India’s influence inside Pakistan, and, more generally, weaken India’s political and economic influence in the region. Pakistan’s support for peacemaking processes in Afghanistan is more often than not reactionary, opportunistic, lacking in strategic depth, and dictated by its national interest. Moreover, the Afghan government has never wanted the peace process to be managed and controlled by Pakistan. There remains a deep lack of trust between these two states stemming from their historically broken relationship and previous manipulative actions by Pakistan during Afghan peacemaking process.

Elections

The collapse of talks between Taliban and the United States also had an impact on the Afghanistan 2019 presidential elections. Despite skepticism about conducting the presidential elections in September 2019 and fears of violence by Taliban at polling station, people cast their ballots in relative safety in comparison to previous elections. That said, turnout was particularly low. Initially, voter turnout was estimated at 2.6 million votes cast, with the final figure being much lower. There are two clear reasons for this low voter turnout. First, not only were there security concerns based on Taliban threats, but many in Afghanistan have lost trust in the election process. This loss of trust has been largely motivated by a lack of transparency and fraud in the 2014 presidential elections and the recent parliamentary elections in 2019. Second, the population has increasingly lost trust in the government and other political elites in Afghanistan. Among Afghans, the collapse of the peace talks only increased their mistrust of domestic political processes and their leaders.

Continued ambiguity surrounding Afghan peace processes and elections has the potential to create a space that could easily be filled by insurgents, including Taliban, which could further escalate the intensity and geographical expansion of violence around the country. This gap could also facilitate an environment ripe of community radicalization in various Taliban held provinces and districts. The critical question, now, is what will happen if the US withdraws from Afghanistan without a political settlement or peace deal.

Complete US military withdrawal from Afghanistan would have both a symbolic and practical impact on security and development. US withdrawal will also, in all likelihood, means a withdrawal of US allied forces. The notion of withdrawal has already created an image of instability and fear among the population. This fear is compounded by the externally dependent economy and the nature of politics in Afghanistan that have created an image of a country unable to manage its crises and conflicts, and defend its borders without external support.

There are three major consequences of US withdrawal from Afghanistan. Without a peace deal, all three would impact the country’s stability in the long term. Withdrawal has the potential to transform the country into a radicalized state, disrupt regional order, and undermine US liberal values, include the liberal international order. On the one hand, Afghanistan is politically fragile and militarily weak, meaning it will remain an area ripe for insurgencies and radical ideologies both of which would set the country’s development back for generations. On the other hand, Russia is increasingly seen as major player in the region and as an actor that could play a role in the political hegemony of the region. Given the geographical position of Iran and its anti-American regime, there is potential for this regional player to influence and mobilize parts of Afghanistan against the US by financing terrorist groups.

Taken together, withdrawal of the United States will serve to undermine the development of the liberal order upon which US political doctrine is based. This liberal order represents a break with oligarchic societies and authoritarian regimes. Considering Afghanistan’s weak state and economy, complete US withdrawal could trap the country in perpetual civil war or lead to the rise of authoritarian governance. Moreover, withdrawing US troops from Afghanistan without an agreement would reduce US leverage in any future peace process and leave behind an even weaker Afghanistan state, military, and economy that could easily turn into a safe haven for terrorists.

Resumption of the Talks

Zalmai Khalilzad launched a new phase of the Afghan peace process in October 2019 by meeting with Pakistani leadership, the Chinese, Russians, European, and NATO and UN allies. According to Taliban representative, a meeting took place between their delegation leader, Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, and Khalilzad on October 5. Although these meetings are not negotiations, the inclusion of all these stakeholders suggests the peace process will take a turn toward a fresh round of talks. Moreover, it is hoped these diplomatic efforts will create a consensus on peace in Afghanistan and foster an environment for a comprehensive intra-Afghan peacemaking process.

The question remains, however, whether resuming talks and starting a new phase of peacemaking in Afghanistan will address the issues created by halting the process in September 2019. If peace talks are to restart, either as an outcome of this prisoner exchange or political pressure, the talks must include all of the issues and the parties to the conflict. In recognizing the Afghanistan conflict is not an internal war, any peacemaking efforts must emphasize ways to address the interests of regional states. This is paramount for future stability of Afghanistan. If regional players and, particularly Pakistan, India, Iran, Russia and others in the Central Asia region do not see their interests met in any future peace accord, they will continue to play the role of spoiler during both the process and implementation phases respectively.

|

| Presidents Trump and Ghani at US Bagram Base in Afghanistan [Getty] |

Restarting peace talks could help reenergize the momentum among nonviolent non-state actors, such as civil society organizations, grassroots movements, and education institutions to resume their peace building efforts. The engagement of nonviolent non-state actors and organizations could also prevent Taliban from influencing the Afghan population through strategies of radicalization. Though future results remain unknown and unpredictable, the process of inclusion itself will (at a minimum) help improve the current situation tremendously.

These efforts could work to complement national level peace processes, create trust building, and legitimize any forthcoming political settlement. A population’s trust and confidence in a peace process is essential and, particularly with regards to local level peacemaking processes that can lead to reconciliation. Trust and confidence in these processes serves to increase people’s willingness to get involved in peace activities, mobilizing others to join these efforts rather than insurgents, and contribute resources. Most crucially, broad-based trust and confidence in peace processes serves to legitimize any peace-oriented outcome such as a peace agreement negotiated through a political settlement.

Forthcoming peace efforts must include

• A neutral thirty party to facilitate the talks, if they are to resume. The US has the potential to play the role of neutral third party to oversee the implementation of a deal after a peace agreement is signed, but not during the process of peace talks. The US is not only the primary party to the conflict, but also actively engaged in the negotiation process.

• A negotiated ceasefire among all the parties. This is a critical first step to stop intense fighting and the killing of innocent people. The ceasefire will not only have an impact on the negotiation process, but will help to address the grievances of the wider population who have lost trust in the process. The ceasefire will serve to gain their confidence and trust, helping to legitimize any peace-oriented outcome.

• Starting with multilateral rather than bilateral talks by including a broad spectrum of the Afghan polity and regional actors, and particularly Pakistan.

• Negotiations that lead to an accord with components to address local security arrangements, the nature of the state /governance, and economic assistance based on prioritizing institution building and nation building.

• Besides reaching a deal with Taliban, if any renewed talks, as Trump hopes, should consider developing a comprehensive regional agreement with Pakistan, Russia, China, and India with an objective of regional stability as it has profound impact on the implementation of peace accord. A peace deal inclusive of a comprehensive regional economic plan that builds on existing economic projects such as the Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India Gas Pipeline (TAPI); Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Afghanistan (TUTAP); Transmission and trade project (CASA, 1000); and Lapiz Lazuli. All of these create further connections through trade and business. As such, countries in the region can benefit from the strengths rather than weaknesses of their neighbors.

-

Aime Williams in Washington and Amy Kazmin, “Trump says talks with Taliban have resumed”, The Financial Times, November 28, 2019 https://www.ft.com/content/75775a58-1217-11ea-a225-db2f231cfeae

-

Phil Stewart, “Exclusive: U.S. troop drawdowns in Afghanistan 'not necessarily' tied to Taliban deal – Esper”, Reuters, December 3, 2019 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-afghanistan-exclusive/exclusive-us-troop-drawdowns-in-afghanistan-not-necessarily-tied-to-taliban-deal-esper-idUSKBN1Y62FG