Four main political issues dominate the ongoing conflict in Yemen in the 21st century: (i) the Houthi resistance movement in the city of Sadah starting in 2004, where Shia Zaydi revivalists struggled with the government on mainly regional economic issues; (ii) from 2007 on (1), the rise of the Southern Movement, a populist protest movement for social justice from Northern Yemen and for local autonomy that has become increasingly more radical – ultimately calling for secession from Northern Yemen; (iii) the Yemen Arab Spring in early 2011 as an emancipatory movement articulated by massive demonstrations in the capital Sana’a and other cities involving hundreds of thousands of pro-democracy protesters, young people, civil society, women, and unemployment people, and demanding equitable employment, access to services, greater autonomy, and resolution of other grievances; and (iv) recently, the COVID-19 pandemic. This explosive mix of grievances has pushed Yemen to become a failed state.(2)

In Yemen, the goal of the revolution in 2011 was to unite the people's wishes to challenge all aspects of the country's dominant system: corruption, nepotism, tribalism, etc. This movement, where the mobilization came from the bottom up, was a threat for the ruling political, tribal and military classes.(3) The Yemeni Spring united all those forces that had had enough of the dominant manipulators. Like many movements the spirit was high when the revolution started, and the National Dialogue was established.(4) Many young, creative Yemenis put their hearts into it. But over time a tiredness emerged and the old elite stepped in: the military, the politicians, and parties, demanding to be paid by UN for their advice and slowly bringing back the old system.(5)

In November 2011, international concern that growing instability would leave Yemen exposed to al-Qaeda and other extremist organizations resulted in a Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Pact signed by the European Union, Saudi Arabia, the Gulf Countries and the United States, in which the conflicting Yemeni parties were persuaded to enter peace talks. The Pact was established for a two-year period of political transition under the process of the National Dialogue Conference, (leaded by the UN).(6) The initiators of the revolution were slowly removed from the decision-making levels and the old struggle between the rulers resumed. They all claimed that they were presenting revolutionary thoughts. In essence, only President Saleh was removed. His clique was still there, through which Saleh could undermine the new president's power.

The new President, who was the Vice-President under Saleh, was just part of the same old system, according to the revolutionaries. Consequently, in the end nothing changed in the way foreseen during the Yemen Spring, which resulted in ongoing conflicts. On 4 March 2015, Houthi militants raided the National Dialogue Conference (NDC) Secretariat in Sana’a, therewith suspending its activities. This act of violence was perhaps the most tangible sign that the broad national dialogue failed to set Yemen on a pathway out of conflict and nudge it towards a citizen engagement process to build a more just, equitable and prosperous country. So Yemen was plunged back into full-blown civil strife.(7)

Dynamics of the Regional Balance of Power in Yemen

Currently, Yemen has become a battlefield between two sectarian, regional rivals: Iran and Saudi Arabia.(8) To control the Houthi resistance movement (actually a pro-Iranian Zaidi group), the Yemeni government made six military interventions against them, which resulted in 2007 in a siege for the Houthis (presently named Ansari Allah) controlling the whole Governorate of Sadah and extending their power to vast areas of both Northern and Southern Yemen.(9) The Houthis emerged as the single largest force in the country, overthrowing the government and taking control of the parliament and capital in April 2015. The Houthis' power grab and their capacity to seize control of Yemen in a short time made it difficult for the GCC, especially Yemen's neighbour Saudi Arabia, to remain silent.

A number of factors facilitated the Houthis' power grab in Yemen: the ineffectiveness of Saudi Arabia to hold off the Yemeni government of Abdullah Saleh and to manage the internal dynamics between the various factions; the focus of attention by the Saudis on other regional situations, thereby underestimating the ability and speed of growth of the Houthis; the aid by Iran to the Houthis; and the increasing ability of the Houthis as guerrillas. Economic and military aid have been crucial for the growth of the movement, especially given how poor Yemen is. In recent years, Tehran has provided military, intelligence, logistical and political support.

The Houthis represent a change in the balance of power in Yemen and even the Arabian Peninsula that has opened the door for Iran to become a major player and extend its regional hegemonic ambitions. The resistance movement is trying to emulate Hezbollah in the Arabian Peninsula, representing a clear Iranian threat to the stability of Yemen's neighbours. In response to this threat and to protect its southernmost cities of Ngrran, Jizan and Aseer, Saudi Arabia spearheaded a coalition of nine Arab states to carry out airstrikes on Yemen on 25 March 2015, heralding the start of a military intervention codenamed Operation Decisive Storm, to smash the power of the Houthi movement by demolishing the power structure of the Yemeni state.

![[Reuters]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Photo%201.jpg)

There is a gap in the literature about the links between the Houthi movement in Yemen and Hezbollah and Iran. This is probably due to a lack of interest or because, until now, the issue has not been deemed important. It is academically and empirically important to start a research about the Houthi movement and its influence over the regional and international levels. This would make the research original, and would also be important for policy makers.

Hezbollah has been one of the major successes of Iran's foreign policy in its ambitions to control and have hegemony in the region.(10) So being able to repeat this success in the Arabian Peninsula with another non-state guerrilla movement is enormously important for Tehran. There are two ways to see the relation between the Houthis and Hezbollah. At least according to analysts, the first is the material one, which covers training, funds, etc. The second is an ideological link, but on the latter we are unconvinced as all roads go to Tehran. Nothing is independent and individual in the links between Hezbollah and the Houthis. This is why we think we need to focus on the comparison between the two movements, which becomes important to understand if the Houthis have a role as an Iranian proxy militia and if they can be effective in the regional struggle between Saudi Arabia and Iran.(11)

Yemen has for some time been affected by Saudi Arabia due to the economic imbalance. Saudi Arabia is a rich nation and Yemen is its poor neighbour. They have wide land and sea borders. In addition, there had been disputes between the two nations over Yemeni territories that were possessed by Saudi Arabia after the foundation of the second kingdom of Saudi Arabia in the early nineteenth century. Yemen has gone into a few wars with Saudi Arabia yet could not take back its lands. Saudi Arabia has made considerable effort to influence the local political scene inside Yemen, or in the area, to prevent the existence of a strong and capable Yemeni state, because it is well known that a strong or out-of-control Yemen could destabilize the Saudization of the Arabia Kingdom.

Iran's presence in Yemen is via the Al-Houthi movement. When the Houthis took control of Sana'a on 21 September 2014, it was an extraordinary shock to the Saudi administration, and it was important to keep Iran from getting a position close to the Saudi land and sea borders – particularly since Iran plans to have a solid state neighbouring Saudi Arabia that can be used as a power card against the Saudis, or if nothing else, to make a second Hezbollah in the Arab peninsula against Saudi Arabia, like the first Hezbollah in Lebanon against Israel.

Looking at the incendiary map of the Middle East, it is conceivable to elucidate the strategic equation drawn up by Iran and its security structure and strength in the area. In the space of a few years, Iran has proved to be ready to control four Arab capitals – Beirut, Damascus, Baghdad, and Sana'a, –and so the Saudi Kingdom was forced to stop the Iranian expansion in Yemen. Saudi Arabia began a proxy war against Iran to break its backbone in Yemen and to destroy the Yemeni military force that was built during the rule of Saleh and before that by ex-president A-Hamdi, but it has failed so far.(12)

Under the control of the Houthis, Yemen could be a powder keg. It is close to areas where more than two thirds of the world's oil reserves are located. Furthermore, a state loyal to Iran and possessing ballistic weapons may pose a major threat to Saudi Arabia. Israel has little interest in the Saudi war in Yemen, as if Iran controls Yemen through Houthi militias it will control the Strait of Bab al-Mandab. This means that Iran can force the Israeli military to enter the Indian Ocean through the Red Sea in order to strike Iran were there to be a war between the two nations. The United States of America and its Western allies also have their own geopolitical interests behind the war in Yemen. The Western alliance, especially the US, believe that the security of Israel and Saudi Arabia is part of their national security and thus a threat to either of these two countries is a serious threat to global peace and security. The US believes that Iran's control over Yemen would be catastrophic for its global influence. Iran's control of Bab al-Mandab via the Houthis means giving Iran's allies, Russia and China, a position in this vital stretch of water.

Because of all these factors, a proxy war has taken place in Yemen. There was a convergence of interests among many countries around destroying the power of Yemen, especially after Houthi militias took control of Sana'a, and to prevent the occurrence of security hurdles in Bab al-Mandab, which could threaten international shipping traffic. There is a wide belief in the West that Iran's malicious behaviour in Yemen and its support for guerrilla movements is unacceptable. However, nothing is being done to help the nation's starving people. The economic and media blockade over the past two years has suffocated and led to the annihilation of Yemeni society.(13)

![A boy walks as he collects toys from the rubble of a house destroyed by a recent air strike in Yemen's north-western city of Saada [Reuters]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Photo%203%20A%20boy%20walks%20as%20he%20collects%20toys%20from%20the%20rubble%20of%20a%20house%20destroyed%20by%20a%20recent%20air%20strike%20in%20Yemen%27s%20northwestern%20city%20of%20Saada%20%28Reuters%29.jpg)

What is new? The COVID-19 pandemic and the balance of the power in Yemen

International and local powers both play a major role in the conflict in Yemen. For many years, the inside threat has been the dominant threat to the state, such as radical groups like AQPA, which have had a catastrophic impact on the government and regional powers, thanks to their opportunism, and exploitation of chaos at different times. Certainly, COVID-19 and its aftermath will likely reorder the existing priorities of each state, pushing the fight against terrorism down the priority list. This kind of radical shift would have one effect: reviving the control of the extreme groups in some areas in the world, especially fragile states, and Yemen for sure. The longer the pandemic lasts, with its detrimental financial and social effects, the higher the chances for terrorist groups to increase their influence in Yemen, Iraq, and Syria and spread this to neighbouring countries.(14)

It used to be common for these groups to exploit valuable services, which are delivered directly to the states, and the easiest way to get their hands on it was through humanitarian assistance or by using disaster relief operations like the Pakistani Jamaat-ud-Dawa, an AQ-linked outfit, the Somalian Al-Shabab, and the Lebanese Hezbollah.(15) Conflicts are escalating post-COVID-19 due to the weakening new environment inside or outside undeveloped countries, so there are plans for invasions of some countries or strategic attacks.(16) As can be seen from these models, the case in Yemen is similar but more complicated because they can sometimes create a win-win situation, even in the most trying conditions which are the two governments in the south and north of the country. AQPA is active in four governorates: Al-Jawf, Marib, and some places in Saada and Sana’a. This can be seen as a serious indicator of a new threat, especially with the unpredictable spread of COVID-19. (17)

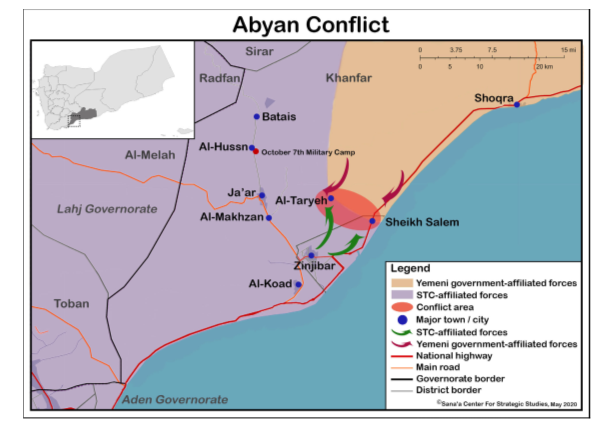

The fight over the south broke out between the Yemeni government forces and those loyal to the Southern Transitional Council (STC) in Abyan in May 2020, threatening to push southern Yemen back into turmoil and risk a shared fight against their armed Houthi movement. The fights followed months of simmering tension between the two sides after the unrealized progress of the Riyadh Agreement, which is a power-sharing deal signed in November 2019 that ended the last round of fighting.(18)

To strengthen the troops based in Shoqra, the Yemeni government brought in forces from Ataq in the neighbouring Shabwa governorate, Marib and Hadramawt. In response, the acting head of the STC in Aden and former governor of Hadramawt, Ahmed bin Breik, threatened to send forces to counter any offensives in Wadi Hadramawt, Shabwa and Abyan. (19) Meanwhile, forces loyal to the STC have been redeployed from some southern governorates (Aden, Lahj and Al-Dhalea) and removed from Abyan.

After fighting broke out, the head of STC, Aiderous al-Zubaidi, who is currently based in the UAE, called on the group’s supporters to “defend the dignity of and the independence of the South." (20) A more inflammatory call to arms came from the STC deputy chairman and former militant Salafist Hani bin Breik, who played a major role in sparking the fighting in Aden in August 2019 by calling for a march on the presidential palace to overthrow what he termed the pro-Islah government.(21) On 18 May, Bin Breik issued a fatwa on Twitter permitting the spilling of the blood of those attacking the South. (22)

While KSA and UAE are united in their military coalition against the Houthi rebels, on behalf of the legitimate Hadi government, each country has its own interests, and as the war wears on, their interests have increasingly diverged. Apparently, the UAE is less interested in defending the Houthis than in furthering its strategic interests: control over the ports, especially Aden’s port, and securing a military presence on the eastern bank of the Red Sea, which would strengthen its military bases in Eritrea. (23)

- Elayah, M. A. A., & Schulpen, L. W. M. (2016). Why do national NGOs go where they go? The case of Yemen.

- Gelvin, J. L. (2015). The Arab uprisings: what everyone needs to know..

- Salamey, I. (2015). Post-Arab Spring: changes and challenges. Third world quarterly, 36(1), 111-129.

- Elayah, M., Schulpen, L., van Kempen, L., Almaweri, A., AbuOsba, B., & Alzandani, B. (2020). National dialogues as an interruption of civil war–the case of Yemen. Peacebuilding, 8(1), 98-117.

- Alwazir, A. Z. (2016). Yemen’s enduring resistance: youth between politics and informal mobilization. Mediterranean Politics, 21(1), 170-191.

- Sharkey, K. K. (2014). Fighting Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula on all fronts: a US counterterrorism strategy in Yemen (Doctoral dissertation).

- Elayah, M., van Kempen, L., & Schulpen, L. (2020). Adding to the Controversy? Civil Society’s Evaluation of the National Conference Dialogue in Yemen. Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 1-28.

- Tzemprin, A., Jozić, J., & Lambare, H. (2015). The Middle East Cold War: Iran-Saudi Arabia and the way ahead. Politička misao: časopis za politologiju, 52(4-5), 187-202.

- Arafat, A. A. D. (2020). Iran’s, Saudi Arabia’s Defense and Security Strategy. In Regional and International Powers in the Gulf Security (pp. 99-132). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

- Zimmerman, K. (2019). Taking the Lead Back in Yemen. AEI Paper & Studies, 1.

- Esfandiary, D., & Tabatabai, A. (2016). Yemen: an Opportunity for Iran–Saudi Dialogue? The Washington Quarterly, 39(2), 155-174.

- Salisbury, P. (2015). Yemen and the Saudi–Iranian ‘Cold War’. Research Paper, Middle East and North Africa Programme, Chatham House, the Royal Institute of International Affairs, 11.

- Elayah, M. A. A., Schulpen, L. W. M., Abu-Osba, B., & Al-Zandani, B. (2017). Yemen: a forgotten war and an unforgettable country.

- Basit, A. (2020). The COVID-19 Pandemic: An Opportunity for Terrorist Groups? Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses 12, no.

- Colin P. Clarke, “Yesterday’s Terrorists Are Today’s Public-Health Providers,” Foreign Policy, April 8, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/04/08/terroristsnonstate-ungoverned-health-providers-coronaviruspandemic/

- “Contending with ISIS in the Time or Coronavirus,” International Crisis Group, March 31, 2020. https://www.crisisgroup.org/global/contending-isis-time-coronavirus

- Raghavan, Sudarsan. "As Yemen’s War Intensifies, an Opening for Al-Qaeda to Resurrect Its Fortunes." The Washington Post, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/as-yemens-war-intensifies-an-opening-for-al-qaeda-to-resurrect-its-fortunes/2020/02/24/6244bd84-54ef-11ea-80ce-37a8d4266c09_story.html.

- Sana'a Center. (2020, June 18). A Grave Road Ahead – The Yemen Review, May 2020. Retrieved June 22, 2020, from https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/10047

- “Army takes military camp outside Abyan capital as STC deploys in Aden,” Al-Masdar Online, May 13, 2020, https://al-masdaronline.net/national/783

- Ahmed al-Haj and Samy Magdy, “Yemeni separatists, government forces clash in the south,” The Associated Press, May 12, 2020, https://apnews.com/e1be7c65423015cb79eefcccf131f720

- Hani bin Breik, Twitter post, “Southern Transitional Council statement [AR],” August 7, 2019, https://twitter.com/HaniBinbrek/status/1159085348074545152

- Hani bin Breik, Twitter post, “Every southerner who fights on the frontlines ... [AR],” May 18, 2020, https://twitter.com/HaniBinbrek/status/1262376113579462656

- Al Jazeera Centre for Studies Established in 2006. (n.d.). Declaration of Autonomy: The Gradual Erosion of Authority in South Yemen. Retrieved June 23, 2020, from https://studies.aljazeera.net/en/policy-briefs/declaration-autonomy-gradual-erosion-authority-south-yemen