Retired general Khalifa Haftar stated his Libyan National Army (LNA) had a "popular mandate" to rule Libya and vowed to press his assault to seize Tripoli. In a televised address on his Libya al-Hadath TV channel, he announced “the general command is answering the will of the people, despite the heavy burden and the many obligations and the size of the responsibility, and we will be subject to the people's wish.” (1) He also declared "the end of the Skhirat Agreement," a 2015 United Nations-mediated deal that consolidated Libya's government. Haftar vowed his forces would work "to put in place the necessary conditions to build the permanent institutions of a civil state." However, he did not specify whether the House of Representatives in Tobruk, eastern Libya would support his plans. Haftar’s unilateral Egypt’s 2013 Sissi-like-style declaration of “popular mandate” and intention of imposing some de facto authority in Libya entail serious ramifications and indicate what could be a third legitimacy crisis in the last six years. Haftar’s plans usher to more escalation of an open-ended crisis, which the United Nations Secretary General considers to be a “proxy war”. Another diplomatic puzzle is the future of the Libyan Political Agreement, also known as the Skhirat Agreement," signed on 17 December 2015 at a conference in Skhirat, Morocco.

After a 31-month tenure as UN special envoy to Libya, Ghassan Salamé submitted his resignation to the UN Secretary General António Guterres for ‘health reasons’ March 2, 2020. His decision implied deep frustration in his pursuit, for more two and a half years, “to unite Libyans, prevent foreign intervention, and preserve the unity of the country". (2) The Trump administration has refused to vote for the appointment of former Algerian foreign minister Ramtane Lamamra to replace Mr. Salamé. The U.S. mission to the UN gave no further explanation for opposing Lamamra, who served as Algeria's foreign minister (2013-2017).

This paper examines what seems to be the dynamo factor, or driving force, of the Libyan conflict: fluctuation and reconstruction of political legitimacy. Since the summer of 2014, two battles over legitimacy, or two legitimation crises, have spoiled Libyan politics and weakened the UN mediation with two rounds of international recognition of one new political institution or another. Both institutions have required separate budgets of the oil revenues for the rival entities and their respective governments, and claimed distant interpretations of ‘legitimacy’ in the eyes of Libyans and the rest of the world. Moreover, most of the political process and interaction with either the United Nations or foreign governments has been constrained by an ego-inflated dilemma of personal animosity between four particular figures with opposite views, scopes of power, and foreign affiliations.

This part 2 of the paper also probes into the struggle of the UN diplomacy, as it had passed its eighth-year mark September 16, 2019. It examines four main factors. First, the construction of a double-edged legitimacy of two competing institutions: House of Representatives in Tobruq with its government housed in Bayda versus GNA in Tripoli. Second, the foreign interference of certain countries, like Egypt, UAE, Turkey, Qatar, France, and Russia, and the United States has pursued tilting the already flimsy balance of power on the ground in favor one player against another. Third, The Libyan conflict has been subject to several diplomatic initiatives by the African Union (AU), the Arab League (AL), the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), the Organization of the Islamic Cooperation (OIC), and the European Union (EU). For instance, the AU initiative opted for a non-removal policy of the Qaddafi regime; but, committed to a “reform process and a political transition.” (3) Fourth, the mismatch between the discourse of ‘national unity’ and the discourse of ‘counterterrorism’ since General Haftar has pledged to “cleanse” the Western part of the country from the perceived “terrorists”. The paper draws on my study of the Libyan case among other Arab conflicts, my previous writings, and fieldwork while serving on the UN Panel of Experts.

Part 1 can be acceded through this link:

https://studies.aljazeera.net/en/reports/libya%E2%80%99s-zero-sum-polit…;

![Khalifa Haftar and commanders of the Libyan National Army [Getty]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Photo%2015%20Khalifa%20Haftar%20and%20commnaders%20of%20the%20Libyan%20National%20Army%20%28Getty%29.jpg)

Libya’s International Linkages

As the famous idiom goes “too many cooks spoil the broth”, the Libyan conflict is a good example of how the scope of differences and the extent of geopolitical external interests in the country cannot be contained or overcome. I have often argued if internal stakeholders in Libya, Syria, Yemen, or elsewhere could free themselves up from foreign manipulation and focus on figuring out a sustainable solution on their own terms, the prospects of finding a compromise, by either their own initiative or the UN mediation efforts, would be rewarding. The interference of certain regional states, as well as superpowers, has solidified the stubbornness and obduracy of these conflicts. Prime Minister Serraj has stated foreign interference “is making the situation more difficult. It is not helping Libyans sit down and find a solution.”

The role of Haftar has attracted increasing bids of support by several Gulf and European states, and recently Trump’s White House, for various reasons. The Libyan bazaar has displayed the rise of Islamist groups, threats of Jihadi militias in Derna, the fight over the Oil Crescent, waves of sub-Saharan migration, and possible future arms deals should Haftar succeed in becoming minister of defense, or possibly leader, of new Libya. Between June 14 and 25, 2018, The United Nations noted a collation of armed groups attempted to seize control of oil facilities in the Oil Crescent. The Libyan National Army announced it would transfer management of the oil facilities to a non-recognized national oil corporation. These developments have prevented some 850,000 barrels per day from being exported and causing a loss of more than $900 million for Libya. (4)

The UN Panel of Experts received independent, corroborated reports from multiple confidential sources that “Egypt has conducted air strikes against targets in the oil crescent to support the recapture by LNA of a number of oil terminals. Egypt denied that the Egyptian Armed Forces carried out these strikes.” (5) Steven Cook of the U.S. Council on Foreign Relations explains how certain states have decided in investing in Haftar’s military power in the field; “Thus the Egyptians, Saudis, Emiratis, Russians, and French have bet on Haftar to repress Islamists and establish stability. For the French, Haftar may also be helpful in stemming the flow of migrants to Europe and protecting their oil interests. Given the internal and external dynamics that are driving support for Haftar, he may be able to carry on his fight for a long time.” (6)

During his visit to Moscow in August 2017, the welcoming ceremony for Haftar was “like a foreign leader already in office, arranging meetings with high-ranking ministers as well as security officials.” (7) Putin’s Kremlin adopted a two-part strategy: empowering Haftar and providing logistical and technical support for his National Army, while avoiding any apparent violation of the U.N. arms embargo. Some reports have revealed Moscow “could send weapons through Egypt, a pro-Haftar neighbor that borders the Haftar-held parts of eastern Libya and is said to have hosted Russian Special Forces.” (8)

![National Libyan Army [Getty]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Photo%2012%20National%20Libyan%20Army%20%28Getty%29.jpg)

Turning west, President Trump’s position on Libya has shifted from downsizing the United States Libya policy, or as he stated in April 2017 “I do not see a role in Libya” except “getting rid of ISIS. We’re being very effective in that regard.” (9) Two years later, he decided to highlight the Haftar factor in more than area of counterterrorism and geopolitics during their famous phone call April 15, 2019. According to the call readout issued by the White House, Trump and Haftar spoke about “the need to achieve peace and stability in Libya,” and the president “recognized Field Marshal Haftar’s significant role in fighting terrorism and securing Libya’s oil resources, and… discussed a shared vision for Libya’s transition to a stable, democratic political system.” This personal interaction between the two men amounted to an endorsement of Haftar’s five-year quest to establish himself as Libya’s leader.” (10)

The political silhouette of General Haftar gained more significance as well in the eyes of the military establishment in Washington. Then-acting U.S. Defense Secretary Patrick Shanahan underscored “a military solution is not what Libya needs,” and supported Haftar’s “role in counterterrorism” and that Washington needed Haftar’s “support in building democratic stability there in the region.” In the same week, both the United States and Russia said they could not support a U.N. Security Council resolution calling for a ceasefire in Libya. (11) One can argue Haftar’s claim of combatting ‘terrorists’ in eastern Libya has been an oversold narrative for several European, U.S., and Gulf states in justifying the support of his armed campaign to capture the capital Tripoli. When the battle of Sirte escalated against ISIS, Haftar’s rivals, Misrata Brigades, fought along with the national unity government while Haftar refusing to join.

French President Immanuel Macron hosted more than one meeting between Haftar and Serraj in Paris. He made several calls for an unconditional ceasefire, but rejected by Haftar. After the talks between the three men in November 2018, Macron's office said the President reiterated France's priorities in Libya: "Fight against terrorist groups, dismantle trafficking networks, especially those for illegal immigration, and permanently stabilize Libya." (12) The dominant view in the French government circles is that strongman solutions are "the only way to keep a lid on Islamist militancy and mass migration.” (13)

![Gen. Haftar meeting French president Macron in Paris [Reuters]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Photo%2017%20Gen.%20Haftar%20meeting%20French%20president%20Macron%20in%20Paris%20%28Reuters%29.jpg)

The French position seems to go along the objectives of the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia not only in military of economic dimensions, but also as part of a regional ideological battle within the large calculation of the uprisings of 2011 and 2019 across the region. Steven Cook notices, “None of these countries ever believed in the promise of the Arab uprisings to produce more open and democratic societies. Their view is that the uprisings have only empowered Islamists and sown chaos. They also regard the internationally recognized government as one that is aligned with the Muslim Brotherhood, Qatar, and Turkey—enemies of the governments in Cairo, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi.” (14)

The irony of the UN high-and-low diplomacy in Libya entails the defiance of field commanders in the military and armed militias of the negotiated political agreements in foreign capitals. One good example is the Libyan Political Agreement (LPA) signed in Skhirat in Morocco December 17, 2015. Four years later, Ghassan Salamé has cautioned repeatedly against the interference of more than regional and international power in the Libyan conflict. As he told the 15-state member Security Council, “More than ever, Libyans are now fighting the wars of other countries who appear content to fight to the last Libyan and to see the country entirely destroyed in order to settle their own scores.” (15) He also bemoaned that the weapons delivered by foreign supporters are “falling into the hands of terrorist groups or being sold to them… This is nothing short of a recipe for disaster.” (16)

As I wrote in a previous publication, Haftar remains a powerhouse in the militarization of the conflict and a bulwark against Islamist groups with growing external support. He managed to secure arms and maintenance for his army equipment despite the UN arms ban on Libya. He has positioned himself as the savior of post-Gaddafi Libya with the trajectory of assuming the presidency, while maintaining a pivotal role in any peace or war proposition. He has also positioned himself as the key figure in confronting migration, and implied the possibility of a deal with the Italians. “For the control of the borders in the south,” he proposed, “I can provide manpower, but the Europeans must send aid, drones, helicopters, night-vision goggles and vehicles.” (17) In his rebuttal, Serraj maintains it is not a war between Libya’s east and west; “It is between people who back civilian government and those who want military rule.”

![President Macron stands between Fayez Sarraj and Khalifa Haftar [Reuters]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Photo%2018%20President%20Macron%20stands%20between%20Fayez%20Sarraj%20and%20Khalifa%20Haftar%20%28Reuters%29.jpg)

Parallel or Rival Diplomacies?

From the onset of the Libyan conflict, several complexities caused by the NATO military intervention in 2011, subsequent humanitarian and peacemaking missions, and other normative responses to regime change have entangled in the UN mediation process. This mediation has also coincided with competing diplomatic initiatives and distant trajectories pursued by the African Union (AU), the Arab League (AL), the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), the Organization of the Islamic Cooperation (OIC), and the European Union (EU). For instance, the AU initiative opted for a non-removal policy of the Qaddafi regime; but, committed to a “reform process and a political transition.” (18) As Azar would say, the Libya conflict has “propensity for involving neighboring communities and states, and even super powers.” (19) Similarly, the 10th ministerial meeting of Libya’s neighboring countries, held in Cairo agreed on a "rejection of any external interference in the internal affairs of Libya."

Libya remains a strategic supplier of energy for most southern European countries. France and Italy are on the top of the list of oil importers from the southern shore. Libya has the largest proven crude oil reserves in Africa at 48.4 billion barrels. It has produced some 1.6 million barrels per day at one point in time before the collapse of Qaddafi regime. A Libyan government audit, conducted in 2017, estimated the total value of fuel smuggled out of the country at $5bn a year. Some observers highlight the fact that Paris has been quietly involved at least since 2015 “in building up the flashy uniformed baron of Benghazi as a strongman it hopes can impose order on the vast, thinly populated North African oil producer and crack down on the Islamist groups that have flourished in the ungoverned spaces of the failed state.” (20)

In January 2019, Italy’s Deputy-Prime Minister, Matteo Salvini, was blunt in directing his criticism to Macron; “France has no interest in stabilizing the situation, probably because it has oil interests that are opposed to those of Italy.” This statement provoked the anger of the Élysées, and caused a diplomatic row between Rome and Paris. The French government summoned the Italian ambassador to give an explanation. Meanwhile, Haftar has made little secret of the modern French weaponry he has acquired despite a U.N. arms embargo. (21)

Macron had hosted a well-publicized meeting between Libyan rival leaders, Fayez Serraj, Khalifa Haftar, Aguila Issa, and Khalid al-Mishri in mid-2018 in Paris. They made news headlines with their ‘agreement’ on holding the presidential and parliamentary elections in early 2019. Ironically, France needed Haftar to be included in the peace dialogue because “he is in control of the Libyan areas where France's interests lie, which means its oil wells in the Sirte Basin,” (22) as Gabriele Lacovino of the Rome-based Center for International Studies explains. Macron described the accord as “historic” and an “essential step towards reconciliation.” Representatives from EU countries, the United States, and regional neighbors were supportive of the agreement.

![Transfer of arms into Libya despite the UN ban [Getty]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Photo%2016%20Transfer%20of%20arms%20into%20Libya%20despite%20the%20UN%20ban%20%28Getty%29.jpg)

Turning south, the African Union called, in early 2019, for an international conference on reconciliation in Libya. Three African nations, South Africa, Ivory Coast and Equatorial Guinea, introduced a resolution draft, in October, to appoint a joint African Union-United Nations envoy for Libya, in an apparent attempt to replace Ghassan Salamé. A leaked copy of the resolution draft expressed “deep concern over the security situation in Libya and the risk of a dangerous military escalation.” It also called for compliance with the arms embargo and condemned “continued external interferences that are exacerbating the already volatile situation on the ground.”

The stalemate in the Libyan conflict was also a diplomatic showdown between Egypt and Qatar at the UN 74th General Assembly in September 2019. Egyptian President Abdel Fattah Sissi, a close ally of UAE and a supporter of Haftar, sought to play the counterterrorism card in justifying Haftar’s armed campaigns as a ‘fight against armed militias’ inside Libya. He told delegates of the 193-member states of the United Nations, "We need to work on unifying all national institutions in order to save our dear neighbor from the ensuing chaos by militias and prevent the intervention of external actors in Libya's internal affairs.” (23) Five months earlier, Sissi reportedly spoke to Trump at length about the need to support Haftar and not “leave him out in the cold”, during his visit to the White House. However, Qatar's Emir, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani, accused Haftar's forces of carrying out war crimes with impunity and with the support of countries that were undermining the GNA and U.N. peace efforts. He told the General Assembly "the latest military operations on the capital Tripoli have thwarted the holding of the comprehensive Libyan national conference." (24)

Earlier I addressed what seems to be fatigue of the UN diplomacy in securing a sustainable truce between Haftar’s forces and the GNA military. Other interpretations have called it ‘diplomatic paralysis’, which has pervaded this state of affairs. The International Crisis Group notices the Security Council members are, in 2019, more than previous years, “divided and unable to call for a cessation of hostilities, mostly owing to U.S. opposition to a draft resolution that would have done just that. The U.S. claims it resisted the draft resolution because it lacked a mechanism to ensure compliance, but its stance more likely reflected White House sympathy for Haftar and for his Saudi, Emirati and Egyptian supporters.” (25)

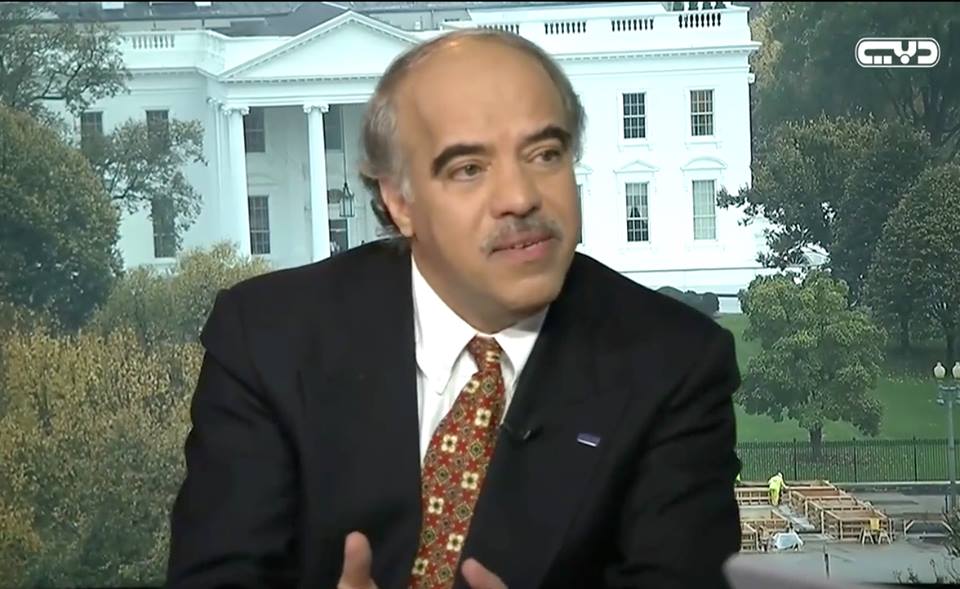

In his testimony before the U.S. House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Middle East, North Africa, and International Terrorism, Thomas Hill, senior program officer at USIP, explained the causality of the struggling UN mediation in Libya. He stated “If “Plan A” was to allow the United Nations to resolve the Libyan conflict; that experiment has failed. The United Nations was not able to constrain external actors who frequently sought to advance narrow self-interest at the expense of peace and stability in Libya. The United Nations was not given the resources or mandate necessary to fulfill its charge; in retrospect, a political mission did not have the coercive power to constrain internal spoilers and external actors.” (26)

![Thomas Hill senior program officer at USIP delivering his briefing at Congress [Reuters]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Photo%2019%20Thomas%20Hill%20senior%20program%20officer%20at%20USIP%20delivering%20his%20briefing%20at%20Congress%20%28Reuters%29.jpg)

This mix bag of international and cross-Mediterranean initiatives of diplomacy is adding to the complexity of the Libyan conflict. The UN mediation seems to be sandwiched amidst the thick layers of the hidden agendas and strategic interests of outside stakeholders’ and their realist involvement in Libya. This overlap of interventions and disparity of the pursued political trajectories, as imposed by several states like France, the United States, Egypt, UAE, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and others in 2019, have undermined extensively the possibility of a reaching a permanent political solution for Libya. Accordingly, the United Nations may need to go back to the drawing board and to affirm the singularity of its mediation process. In other words, one track of UN mediation to be reflected in the Security Council upcoming resolutions.

What is behind the Counterterrorism Discourse?

Since early 2015, Haftar has positioned himself as Libya’s driving force in counterterrorism, while leading his self-proclaimed Libyan National Army and ‘Operation Dignity’. He has often sugarcoated his fierce military attacks in eastern and, later, western Libya with the alleged ‘pursuit of eradicating jihadi groups. Besides the external support, he has also galvanized the allegiance of several armed groups, including the 106th Infantry Brigade, the Tarhouna-based 9th Infantry Brigade, Chadian and Sudanese rebels, and some elements associated with Gaddafi’s son Saif al Islam. Haftar experimented his anti-terror venture by targeting Ansar Al Sharia, a self-identifying Jihadist group in Benghazi in eastern Libya in 2015, before zooming on Derna, and extending his armed campaign towards Tripoli in the west with a rebranded ‘End of Treachery’ Operation in 2019. Back in April 2019, he asserted, “We hear your call, Tripoli. It is now the time for the great victory. March forward.” A senior French official said support for Haftar is partly driven by the imperative of stanching the supply of arms and funds to jihadist groups threatening fragile governments in Niger, Chad and Mali, which are backed by France’s Operation Barkhane. (27)

One of the worst single atrocities of the Libyan civil war occurred in July 2019, and killed at least 53 refugees at a detention centre near Tripoli. This fatal incident is one of many cases of attacks launched by Haftar’s forces with foreign logistical support. The UN arms experts suspected ‘foreign fighter jets’ were involved in the attack. (28) Former British ambassador to Libya, Peter Millett points out “the only two countries with capacity and motive to mount the strike were the UAE and Egypt.” (29) He called on the Security Council to discuss, at ambassadorial level, how outside powers are prolonging the conflict in Libya and extending the suffering of the Libyan people. For instance, the United Arab Emirates has plans to dominate the flow of shipping lanes the Mediterranean Sea, and consider Libya’s geographic positions to be important. The Emiratis aspire to exploit the country’s huge energy resources and need for reconstruction.

![[Getty]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Photo%2014%20%28Getty%29.jpg)

In 2019, Haftar’s role and political status have gained momentum by three moves made by three powerful states: a) Saudi Arabia promised tens of millions of dollars, upon the UAE’s recommendation, to help pay for Haftar’s military operation to seize the capital. (30) b) The United States Mission at the United Nations threatened to veto calls for a ceasefire at the Security Council, with a subtle hint of endorsing of Haftar’s counterterrorism narrative. Furthermore, the famous phone call between Trump and Haftar was uplifting for the General’s ego and ambition. In the White House’s call-readout-text included in the same sentence, an ironic linkage between “ongoing counterterrorism efforts” and “building democratic stability” within Libya, as the main theme of the call between the two men. c) France blocked a European Union statement opposing Haftar’s offensive, while citing the need for its own reassurances regarding the alleged ‘involvement of terrorist groups’ fighting Haftar in Tripoli.” (31)

In the eyes of those governments, Haftar’s anti-terror narrative has overshadowed the ferocity and vengeance of his troops from either Islamist groups or GNA supporters. One Libya observer notices Haftar has a history of “repackaging failed military coups as ‘wars on terror’ to justify excessive use of force whilst gaining international legitimacy and political support in the process.” (32) In a ridiculing twist of Haftar’s power inside Libya, Osama al Juwaili, the leading commander of the GNA forces, told the New York Times, “Why all this pain? Just stop this now and assign the guy [Haftar] to rule us!”

![[Getty]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Photo%2013%20%28Getty%29.jpg)

Conclusion: Need for a Blank Slate

The political turmoil and continued killings have entered their ninth year in Libya, while perpetuating a complex intrastate conflict with no apparent light at the end of the tunnel. The Libyan Political Agreement has tilted towards a protracted limbo more existing hopes of reconciliation. Between the high point peacemaking of 2015, when the parties signed the Political Agreement in Morocco, and the low point of military offenses and counter offenses around Tripoli in 2019, the UN diplomacy has shifted into some backpedaling on several issues, notably the elections and the new constitution project. There is also a sense of loss and despair among elites and ordinary individuals either inside Libya or among Libyan diaspora. The balance of power among Haftar’s forces, HoR, GNA, and other stakeholders is fluid. The official government GNA does not have much control in the country. Libya’s UN representative once said, “Many painful years have elapsed in which Libyans have suffered at all levels.”

There was little optimism in the new round of talks scheduled in March 2020 in Berlin. German Chancellor Angela Merkel warned that the Libyan civil war could spiral into a bigger conflict like the one in Syria. The nightmarish scenario of a large influx of migrants across the Mediterranean is imminent should the country slides into a larger civil war. One cannot belittle the skills and reputation of those world diplomats, at the UN, UNSMIL headquarters in Libya, or at various capitals, as they remain sincere is their search for a political solution for Libya. However, one should be cautious of a possible ‘Einstein Quantum Insanity’, when international diplomacy keeps “doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.” The same high wave of optimism rises prior to every meeting in Tunis, Skhirat, Paris, Palermo, and now Berlin. There has been no viable prospect of securing the commitment of the five top men of new Libya, Haftar, Saleh, Serraj, Mishri, and Swehli, to any sustainable political formula.

The UN process of mediation should not compete with any parallel initiatives proposed by certain international bodies or countries, or any latent manipulation of the status quo in favor one group against another. There is consensus among most Libya observers that a permanent political solution is not possible “if external actors and nation-states continue to intervene in Libya in ways that prioritize their own interests over those of the Libyan people.” (33) This paradox of UN mediation and foreign manipulation, by several external actors, defies the wisdom of envisioning a political settlement of the Libyan conflict. Therefore, all international diplomatic gestures need to be aligned and coordinated via the UN platform, with a well-defined trajectory, rather than any zero-game equation or realist calculation. UNSMIL’s mandate can be inclusive of such suggested coordination.

![Former UN envoy to Libya Ghassan Salamé [Reuters]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Photo%2021%20Former%20UN%20envpy%20tp%20Libya%20GHassan%20Salame%20%28Reuters%29%20-%20Copy.jpg)

- DW News, “Libya: Khalifa Haftar declares 'popular mandate,' end to 2015 UN agreement”. DW, April 27, 2020 https://www.dw.com/en/libya-khalifa-haftar-declares-popular-mandate-end-to-2015-un-agreement/a-53264892

- aBBC, “Libya conflict: 'Stressed' Ghassan Salamé resigns as UN envoy,” BBC News, March 2, 2020 https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-51713683

- Peter Bartu, “Libya’s Political Transition: The Challenges of Mediation”, International Peace Institute, December 2014

- UN News, “Despite Some Progress, Libya in Decline, Top United Nations Official Warns Security Council, Calling for Continued International Unity, Support”, SC/13425, July 16, 2018 https://www.un.org/press/en/2018/sc13425.doc.htm

- Final report of the Panel of Experts on Libya established pursuant to resolution 1973 (2011), S/2018/812, September 5, 2018

- aSteven A. Cook, “The Fight for Libya: What to Know”, Council on Foreign Relations, April 19, 2019 https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/fight-libya-what-know

- Lincoln Pigman, “Inside Putin’s Libyan Power Play”, Foreign Policy, September 4, 2017 http://foreignpolicy.com/2017/09/14/inside-putins-libyan-power-play/

- Ibid

- Abby Phillip, “Trump says he does not see expanded role for U.S. in Libya beyond ISIS fight”, April 20, 2017 https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-says-he-does-not-see-expanded-role-for-us-in-libya-beyond-isis-fight/2017/04/20/2e2b735c-25ff-11e7-a1b3-faff0034e2de_story.html?utm_term=.d96710aaa37d

- Steven Cook, “Loving Dictators Is as American as Apple Pie,” Foreign Policy, April 26, 2019 https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/04/26/loving-dictators-is-as-american-as-apple-pie/

- Steve Holland, “White House says Trump spoke to Libyan commander Haftar on Monday”, Reuters, April 19, 2019 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-libya-security-trump/white-house-says-trump-spoke-to-libyan-commander-haftar-on-monday-idUSKCN1RV0WW

- Aljazeera News, “Libya's rebel commander Haftar tells Macron no ceasefire for now, Amy 23, 2019 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/05/libyan-commander-haftar-tells-macron-ceasefire-190523062338818.html

- Paul Taylor, “France’s Double Game in Libya”, POLITICO, April 17, 2019 https://www.politico.eu/article/frances-double-game-in-libya-nato-un-khalifa-haftar/

- Steven A. Cook, “The Fight for Libya: What to Know”, Council on Foreign Relations, April 19, 2019 https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/fight-libya-what-know

- Ghassan Salamé, “With Libyans now ‘fighting the wars of others’ inside their own country, UN envoy urges Security Council action to end violence”, UN News, July 29, 2019 https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/07/1043381

- Ibid

- Patrick Wintour, “Italy's deal to stem flow of people from Libya in danger of collapse”, The Guardian, October 7, 2017 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/03/italys-deal-to-stem-flow-of-people-from-libya-in-danger-of-collapse

- Peter Bartu, “Libya’s Political Transition: The Challenges of Mediation”, International Peace Institute, December 2014

- Edward E Azar, The Management of Protracted Social Conflict: Theory and Cases, Dartmouth Pub Co. 1990

- Paul Taylor, “France’s Double Game in Libya”, POLITICO, April 17, 2019 https://www.politico.eu/article/frances-double-game-in-libya-nato-un-khalifa-haftar/

- aPaul Taylor, “France’s Double Game in Libya”, POLITICO, April 17, 2019 https://www.politico.eu/article/frances-double-game-in-libya-nato-un-khalifa-haftar/

- Interview: Strategic interests behind France's stance on Libya collides with those of Italy”, Centreo Studi Internationli, August 17, 2017 https://www.cesi-italia.org/eventi/625/interview-strategic-interests-behind-frances-stance-on-libya-collides-with-those-of-italy-xinhuanet

- Reuters, “Egypt, Qatar Trade Barbs at UN on Libya Conflict Interference,” September 24, 2019 https://www.voanews.com/middle-east/egypt-qatar-trade-barbs-un-libya-conflict-interference

- Ibid

- ICG, “Avoiding a Protracted Conflict in Libya”, July 22, 2019 https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/north-africa/libya/avoiding-protracted-conflict-libya

- Thomas Hill, “Testimony before the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Middle East, North Africa, and International Terrorism”, USIP, May 15, 2019 https://www.usip.org/publications/2019/05/conflict-libya

- Paul Taylor, “France’s Double Game in Libya”, POLITICO, April 17, 2019 https://www.politico.eu/article/frances-double-game-in-libya-nato-un-khalifa-haftar/

- Patrick Wintour, “Foreign jets used in Libyan refugee centre airstrike, says UN,” The Guardian, November 6, 2019 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/nov/06/foreign-jets-used-in-libyan-refugee-centre-airstrike-claims-un-report

- Ibid

- Jared Malsin and Summer Said, “Saudi Arabia Promised Support to Libyan Warlord in Push to Seize Tripoli,” Wall Street Journal, April 12, 2019 https://www.wsj.com/articles/saudi-arabia-promised-support-to-libyan-warlord-in-push-to-seize-tripoli-11555077600?mod=article_inline

- Anas Elgomati, “Haftar’s Rebranded Coups”, Carnegie, July 3, 2019 https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/79579

- Ibid

- Thomas Hill, “Testimony before the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Middle East, North Africa, and International Terrorism”, USIP, May 15, 2019 https://www.usip.org/publications/2019/05/conflict-libya