On June 6, 2020, the Qatari crisis entered its fourth year with two parallel political discourses, which have endured the complexity of issues between Qatar and the Quartet [Saudi Arabia, Emirates, Bahrain and Egypt] since early June 2017: a) diplomatic hopes in the U.S.-backed Kuwaiti mediation amidst several gestures of rapprochement between the Qataris and the Saudis; and b) disparity of positions by the disputing parties while maintaining status quo politics. The Trump administration has urged the Quartet capitals to reopen their airspace for Qatari airlines as a step toward ending the open-ended blockade. The Wall Street Journal quoted U.S. officials saying "there is a greater sense of urgency to resolve the airspace issue. It's an ongoing irritation for us that money goes into Iran's coffers due to Qatar Airways overflights." (1) The Trump White House has been irritated by the so-called "overfly fees" that Qatar pays to Iran to use its airspace.

There is growing hope Washington’s call will trigger momentum for lifting the land and sea blockade imposed on Qatar as well. Qatar’s foreign minister Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Thani hopes “the initiative will produce results, we are open to dialogue and ready to meet each step forward with 10 steps from our side.” (2) Unlike the Saudis, the Emiratis have maintained the 2017 demands, and UAE Foreign Minister Anwar Gargash insists “this issue will stay with us, and we have to manage it in a better way until we reach a future stage.” He has often characterized the blockade as “a result of Doha's interference policies," and argued "the solution for this crisis should be based on dealing with the causes of it." (3)

As a result, the three-year blockade is causing a hurting stalemate for both sides of the Gulf conflict. In his new book “Qatar and the Gulf Crisis”, Kristian C. Ulrichsen argues the blockade has become “stuck at a political level where the Saudi and Emirati leadership—and especially Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Mohammed bin Zayed—appear reluctant to make the first move to offer concessions or progress to a negotiated compromise.” (4) This paper examines some major narrative turns of the Quartet-Qatar showdown and the transformation of Trump’s position. It traces the possibility of a de-escalation shift along Washington’s pursuit of mediation in the framework of the Kuwaiti diplomacy; and weighs on the future of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), as a counterbalance of the Arab Gulf strategic (dis)unity and common existentialism in a turbulent region.

![Qatar’s foreign minister Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Thani [Reuters]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Photo%209%20Qatar%E2%80%99s%20foreign%20minister%20Mohammed%20bin%20Abdulrahman%20Al%20Thani%20%28Reuters%29.jpg)

While in Doha in May 2018, I was invited to make a presentation entitled “A Geopolitical Outlook of the Gulf Crisis Trajectory: Political and Strategic Variables”, while taking into consideration the region could become a tinderbox of tensions under Trump’s unsettled policy toward Iran and Saudi Arabia and how any U.S.-Iran standoff would be a catalyst in future developments. My aim was to construct a holistic strategy of containing and resolving the conflict. I developed a three-scenario outlook of the crisis: 1) Snowball scenario, 2) Stimulus scenario, and 3) Stalemate scenario.

Claiming the Crystal Ball!

I could see some correlation between Trump’s anti-Iran statements and a possible stalemate of the Gulf crisis. Ripeness theory scholar William Zartman maintains there are two ways of resolving any conflict depending on the substance and temporality of the parties’ efforts for resolution: a) One, of longest standing, holds that “the key to a successful resolution of conflict lies in the substance of the proposals for a solution. Parties resolve their conflict by finding an acceptable agreement—more or less a midpoint— between their positions, either along a flat front through compromise or, as more recent studies have highlighted, along a front made convex through the search for positive-sum solutions or encompassing formulas.” b) Parties resolve their conflict only when “they are ready to do so—when alternative, usually unilateral, means of achieving a satisfactory result are blocked and the parties find themselves in an uncomfortable and costly predicament. At that point they grab on to proposals that usually have been in the air for a long time and that only now appear attractive.” (5)

Zartman leans more towards the parties’ cognitive and psychological mindsets to have a sense of how the conflict modalities may exhaust the parties’ resilience and mindsets. He expects mediators to capitalize on when the parties find themselves “locked in a conflict from which they cannot escalate to victory and this deadlock is painful to both of them (although not necessarily in equal degree or for the same reasons), they seek an alternative policy or Way Out.” (6) Therefore, he keeps the door open for mediators to seize the likelihood of some “objective referents to be perceived”, while considering ripeness as “necessarily a perceptual event.”

Back in May 2018, I examined the Iran connection and its indirect impact on the Gulf crisis within U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s then-twelve demands for Iran as the textbook of Trump’s Iran policy along the prominence of a pro-Israel/anti-Iran strategy and his pursuit of appeasing right-wing and Evangelist groups. I also anticipated President Trump would need Iran as his ‘boxing bag’ for the Congressional election in 2018 and the presidential election of 2020. I quote myself, “After losing the opportunity to score a ‘diplomatic victory over North Korea, an anti-Iran stand becomes more significant as a the only foreign policy asset.”

![U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo speaks at the Heritage Foundation in Washington on May 21 2018 [Getty]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Photo%205%20U.S.%20Secretary%20of%20State%20Mike%20Pompeo%20speaks%20at%20the%20Heritage%20Foundation%20in%20Washington%20on%20May%2021%202018%20%20%28Getty%29.jpg)

As for the Arab Gulf Connection, I foresaw three main variables: a) strength of a Saudi-UAE-American-Israeli axis as a major realignment of U.S. strategic relationships in the region; b) Saudi Arabia would bear embarrassment in Yemen and targeted by missile attacks launched by the Houthis across the border; and c) the Saudi and Emirati money will exhaust its potential in generating political capital in Washington. Now, a number of analysts have reflected how Washington was the host of a Saudi-Emirati-Qatari monumental lobbying battle over U.S. foreign policy. They notice “Riyadh not only failed to make their blockade a success, but saw their influence wane appreciably in the United States as they stumbled from one public relations fiasco to the next. Even their staunchest defender, Donald Trump, recently threatened to sever U.S. military support for the Kingdom if the Saudi royals didn’t end their oil war with Russia (which they promptly did).” (7)

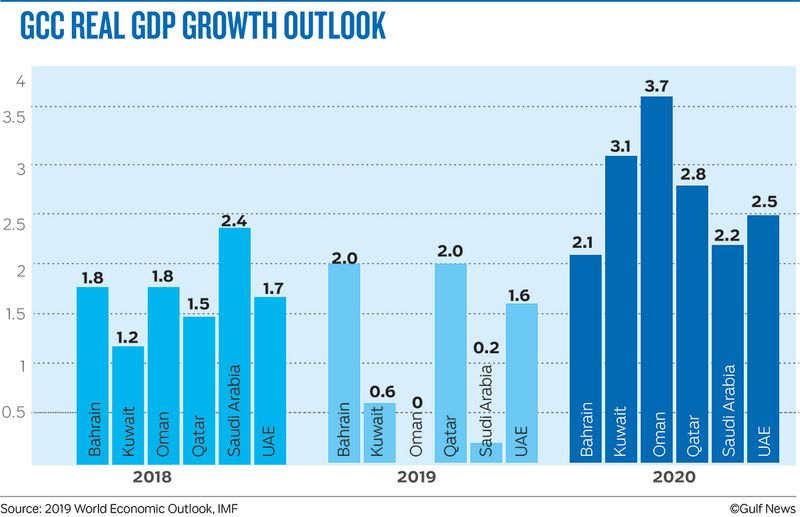

From an economic perspective, I elaborated on Qatar’s spending sustainability beyond the first year of the blockade. I foresaw Doha’s need for $45bn to fund growth in the 2019 and 2020, after it had allocated $38.5 bn, the equivalent to 23% of the national GDP, to support its economy due the impact of the crisis in its first few months. By June 2020, the Qatari economy appears to have made a robust upswing despite the side effects of the Quartet’s embargo. Qatar Chamber of Commerce & Industry (QCCI) stated the blockade has contributed to accelerating economic development and boosting foreign trade, especially with the opening of the Hamad Port and the inauguration of direct sea shipping routes with a number of brotherly and friendly countries. (8)

Chairman Khalifa bin Jassim Al Thani highlighted about 47,000 new companies had been established in Qatar in the last three years. He also mentioned how Qatar’s new legislations and incentives have attracted more foreign investments. According to the Qatar Chamber, 1464 new industrial establishments were registered by the end of 2019 in all industrial sectors, compared to 1171 by the end of 2016. some 293 new factories started to operate in Qatar, including 162 factories in the first year of blockade in 2017, 72 factories in the second year 2018, and 59 factories in the third year 2019.(9)

![Emir of Qatar Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani visited Baladna [dairy] farm [Baladna Twitter]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Photo%203%20Emir%20of%20Qatar%20Tamim%20bin%20Hamad%20Al%20Thani%20visited%20Baladna%20%28dairy%29%20farm%20%28Baladna%20Twitter%29.jpg)

My three-scenario forecast of the trajectory of the Gulf crisis built on several regional and international dynamics:

-

The Snowball Scenario:

This outlook derived from several factors as they coincided in the spring of 2018:

- political mood in Washington and Tehran of mutual escalation and defiance;

- Israel’s tendency to exacerbate the turbulent situation in Syria to provoke Iran;

- Washington would impose extreme trade sanctions on European and other companies and governments if they continue their deals with Iran;

- The Saudis and Emiratis would double their joint efforts to counter the Iranian Influence in concert with Trump’s strategy for branding Iran a regional threat;

- Trump’s pursuit of renegotiating the Nuclear Deal would turn into an open crisis.

- Trump may consider limited attacks on Iranian targets along the Israeli hawkish impulses;

- Doha’s long-term interest calls for diverse exporters and not being over-dependent on Iran and Turkey in trade and military cooperation, and still the Qatari-Iranian relationship could become a possible ‘lock-in effect’ in the Trump Iran policy;

- Democrats will regain the majority in the House in November 2018.

-

The Stimulus Scenario:

- Trump would remain eager to find a "quick and final" solution to the Gulf crisis.

- Kuwaiti Emir’s diplomacy may pick up a new momentum after having his two personal letters delivered to Riyadh and Doha in February and March 2018.

- UAE recognizes Yemen’s sovereignty over Socotra island as a sign of corrective foreign policy.

-

The Stalemate Scenario:

- The Gulf crisis would generate more personal vendetta, especially for MBZ and his advisors.

- MBZ and MBS would lean toward the naturalization of status quo and undermine the U.S. diplomacy of dialogue.

- UAE and KSA will not dismantle the blockade voluntarily and preempt the Kuwaiti mediation efforts.

- Doha, Riyadh, and Abu Dhabi may be entrapped in an echo-chamber situation while managing the Crisis. Therefore, the crisis would be captive of a wait-and-see situation. Then-Saudi foreign minister Adel Al-Jubeir had stated on Feb, 17, 2018, “The solution to the crisis lies with the brothers in Qatar. They know best what they must do.”

- MBZ most likely will not visit the White House and continue to ignore Trump’s pressure to end the Gulf Crisis.

- The expected Gulf-US summit could be cancelled by lack of positive response from Abu Dhabi and Riyadh.

- GCC remains in permanent crisis.

Timeline of the Gulf Crisis

There has been a dominant linear view of the Crisis that advocates considering an open-ended political dilemma that continues on the same pace of complexity of June 5, 2017 in the context of the tacit US-Quartet agreement on demonizing Qatar. However, the use of narrative analysis helps differentiate between four different phases, either in light of the Quartet’s main reasons of the blockade, Qatar’s approaches of containing and managing the Crisis, or the possible ways of ending the conflict. The following chart the time framework and type of interaction across four phases: 1) compatibility on the isolation of Qatar; 2) policy of containment; 3) the Kuwaiti factor; and 4) the White House’s consolidation of the Kuwaiti mediation.

|

May 20 – June 5, 2017 Compatibility on the Isolation of Qatar |

|

|

June 5 – September 7, 2017 Policy of Containment

|

|

|

September 7, 2017 – March 5, 2018 The Kuwaiti Factor

|

|

|

March 5 – End of May 2018 The White House’s Consolidation of the Kuwaiti Mediation |

|

Four Phases of the Gulf Crisis Dynamics [Complied by the author]

The Gulf Crisis has entered another year of divergent expectations among the parties. Any formula of settlement, or positive transformation, remains dependent on a web of dialectical conjunctions: a) dialectic of non-declared political positions behind the scenes; b) dialectic of public narratives circulating across traditional and new media, namely Tweets, which has perpetuated the psychological and political rift behind the virtual reality screens of computers as cellphones; and c) dialectic of the new US-Iranian escalation. Secretary of State Pompeo has publicized the twelve-demand list for Tehran, and waged what amounts to a trade war against the European corporations and governments that have invested in the Iranian market since the signature of the nuclear deal in June 2015. Accordingly, this complexity has shaped the battle of narratives.

-

The Narrative of Dictating Quartet’s Demands

There is a fine line between objective understanding and subjective interpretation of the causality of the Gulf Crisis. Accordingly, the world public opinion was divided into two camps: the first supports the Quartet’s blockade and the subsequent 13-demand list issued in the second week of July 2017.

|

1 |

Scale down diplomatic ties with Iran and close the Iranian diplomatic missions in Qatar, expel members of Iran's Revolutionary Guard and cut off military and intelligence cooperation with Iran. |

|

2 |

Immediately shut down the Turkish military base, which is currently under construction, and halt military cooperation with Turkey inside of Qatar. |

|

3 |

Sever ties to all "terrorist, sectarian and ideological organizations," specifically the Muslim Brotherhood, ISIL, al-Qaeda, Fateh al-Sham (formerly known as the Nusra Front) and Lebanon's Hezbollah. |

|

4 |

Stop all means of funding for individuals, groups or organizations that have been designated as terrorists by Saudi Arabia, UAE, Egypt, Bahrain, US and other countries. |

|

5 |

Hand over "terrorist figures", fugitives and wanted individuals from Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt and Bahrain to their countries of origin. |

|

6 |

Shut down Al Jazeera and its affiliate stations. |

|

7 |

End interference in sovereign countries' internal affairs. Stop granting citizenship to wanted nationals from Saudi Arabia, UAE, Egypt and Bahrain. |

|

8 |

Pay reparations and compensation for loss of life and other financial losses caused by Qatar's policies in recent years. The sum will be determined in coordination with Qatar. |

|

9 |

Align Qatar's military, political, social and economic policies with the other Gulf and Arab countries, as well as on economic matters, as per the 2014 agreement reached with Saudi Arabia. |

|

10 |

Cease contact with the political opposition in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt and Bahrain. |

|

11 |

Shut down all news outlets funded directly and indirectly by Qatar, including Arabi24, Rassd, Al Araby Al Jadeed, Mekameleen, and Middle East Eye, etc. |

|

12 |

Agree to all the demands within 10 days of list being submitted to Qatar, or the list will become invalid. |

|

13 |

Consent to monthly compliance audits in the first year after agreeing to the demands, followed by quarterly audits in the second year, and annual audits in the following 10 years. |

The Quartet’s List of 13 Demands [Complied by the author]

Three weeks before the list was leaked to the media, then-U.S. Secretary of State Tillerson implied some skepticism about the extent of what the Quartet expected from Qatar; "We hope the list of demands will soon be presented to Qatar and will be reasonable and actionable.” (10) The list included a mix bag of demands that apparently oversighted the principle of state sovereignty and other imperatives of international law. As one commentator put it, it was not a “question of demands, but an insult. The tone of these demands and the underlining approach does not only show total ignorance of international relations and a lack of understanding about what state sovereignty means, but it also goes to the heart of a lack of coherence and preparation by the four countries over putting a document like this together.” (11)

By July 19, 2017, the Quartet’s strategy shifted from thirteen “demands” to six “principles” which the four-nation alliance against Qatar framed as the parameters for future talks on how the resolution can proceed.

|

1 |

Commitment to combat extremism and terrorism in all its forms and to prevent their financing or the provision of safe havens |

|

2 |

Prohibiting all acts of incitement and all forms of expression which spread, incite, promote or justify hatred and violence |

|

3 |

Full commitment to Riyadh Agreement 2013 and the supplementary agreement and its executive mechanism for 2014 within the framework of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) for Arab States |

|

4 |

Commitment to all the outcomes of the Arab-Islamic-US Summit held in Riyadh in May 2017 |

|

5 |

To refrain from interfering in the internal affairs of States and from supporting illegal entities |

|

6 |

Responsibility of all States of international community to confront all forms of extremism and terrorism as a threat to international peace and security |

The Quartet’s Alternative List of 6 Principles [Complied by the author]

Officials from the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Egypt spoke to journalists at the United Nations in an attempt to sustain their pressure on Qatar. Emirati ambassador to the UN Lana Nusseibeh maintained that “We’re never going back to the status quo,” said during the briefing on Tuesday. That needs to be understood by the Qataris.” One can argue that there an early indicator of relative disparity between the Emirati and Saudi new positions. For instance, Saudi ambassador at the United Nations Abdallah Al Mouallimi said “we are all for compromise, but there will be no compromise on these six principles.” He added it “should be easy” for Qatar to agree to the six principles, which are similar to the Riyadh agreements signed by the Qatari emir, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, in 2013 and 2014. One of the principles is an explicit call for Doha to abide by those agreements. (12)

The Quartet’s shift from a 13-demand list a six-‘principle’ list had mixed reactions. Some interpretations contested the notion that the Quartet’s position has weakened in a matter of a few weeks. Mohammed Al-Yahya, a Saudi analyst of Gulf politics and non-resident fellow at the Atlantic Council, does not see it as “a softening of the quartet's position on Qatar per se, as much as a measure taken to restart the negotiation process. It is clear that the boycotting nations are prepared to play the long game with Qatar, but there is no doubt that a speedy resolution of the crisis will be in everyone's interest… These six principles are best viewed as an effort to set the foundation for meaningful negotiation process.” (13) Other views have acknowledged the non-feasibility of the original 13-demand list. Brian Katulis, a Middle East policy expert at the Center for American Progress, was not surprised since “there are more voices in all of these countries calling for a more pragmatic step back from the demands which were so maximalist and presented in such a way that makes it hard for Qatar to accept.” (14)

The Quartet States implied a realist discourse of power and alliance against a small nation in the neighborhood while assuming Trump and the rest of the US administration would back up their plans. Bahrain’s foreign minister, Shaikh Khalid Bin Ahmad Al Khalifa, representing the kingdom at the conference in Kuwait late May 2017, said that questions about the end of the crisis should be addressed to Qatar; “the ball is in their field.” (15) Similarly, then-Saudi Arabia’s foreign minister Adel Al Jubeir has reiterated his position that Qatar should transform “from a state of denial to a state of realization of the current situation it is living.” He told his audience during a lecture at the Egmont Institute in Brussels February 23, 2018 that “the Qatar crisis is a small one compared to important issues in the region, and all we want is for [Doha] to stop using their media platforms to propagate hatred… Even though Qatar has signed agreements to stop supporting terrorism that has still not completely happened.”(16)

The Narrative of Contesting Quartet’s Demands

As the famous Newtonian motto goes, “for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.” The alleged charges of ‘supporting’ terrorism did not resonate with numerous analysts and large segments of the world public opinion. Some observers questioned the motivation of the charges against Qatar while the majority of the 9/11 attackers came from Saudi Arabia. To many, the dispute in the Gulf “amounts to the pot blaming the kettle and twisting the truth to serve rival narratives,” as commented one Gulf analyst. (17)

Others rejected the immorality of the Quartet’s land and air blockage of Qatar as an infringement of the humanitarian international law. Several demonstrations took to the street in Switzerland, Germany, and France in protest of Qatar blockade. Sara Pritchett, spokesperson for EuroMed, a human rights organization, condemned the shortage of essential medical equipment and medicines that were not reaching Qatar. As she stated, "The UAE have been a key player in the blockade, and their actions have had a special impact on medicine, commercial trade and separation of families, just to name a few.” (18) In mid-February, Qatar's National Human Rights Committee reported that the Louvre museum apologized and opened an official inquiry into the incident where Abu Dhabi's Louvre Museum map omitted the Qatari Peninsula.

Two weeks into the crisis, the State Department spokeswoman, Heather Nauert, expressed skepticism toward the Quartet states for not baking up their charges against Qatar. “Now that it has been more than two weeks since the embargo has started, we are mystified that the Gulf States have not released to the public nor to the Qataris the details about the claims they are making toward Qatar.” Nauert also raised doubts about the real causes of the animosity toward Qatar; "at this point, we are left with one simple question: Were the actions really about their concerns regarding Qatar's alleged support for terrorism or were they about the long-simmering grievances between and among the GCC countries," in reference to the Gulf Cooperation Council.(19)

![Former US Press Secretary Heather Nauert [Getty]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Photo%208%20Fomer%20US%20Press%20Secretary%20Heather%20Nauert%20%28Getty%29.jpg)

The Quartet’s narratives have sought diligently to construct a dubious image of Qatar as a local enemy. A virtual echo chamber emerged between Abu Dhabi, Riyadh, Manama, and, to some extent, Cairo. The anti-Qatar charges coming from different directions have sustained each other as the growing tide of a turbulent ocean. However, these narratives have implied more than a dilemma of an echo chamber.

Heavy Legacy of Mistrust

The duality of diplomatic hopes and divergence of political wills in Riyadh, Abu Dhabi, and Doha remains one of the nuances of the Gulf crisis in its fourth year. In May, there was another ‘hectic’ diplomatic activity of Kuwaiti, Omani, and Qatari envoys who delivered verbal and written messages in Riyadh and Doha. However, the stalemate continues and Emirati officials seem to be the least interested in a resolution of the crisis. UAE Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Anwar Gargash tweeted: “I do not think that the Qatar crisis, on its third anniversary, deserves comment. Paths have diverged and the Gulf has changed and cannot go back to what it was.”

For more than a decade, Qatar’s political discourse and Aljazeera’s impact on the Arab public opinion, before and during the 2011 uprisings, have irritated most Gulf and other Arab governments. Another factor is Doha’s growing soft power and successful interventions in several international conflicts, including the release of several members of Taliban from Guantanamo prison, Sudan conflict, Hamas-Fatah embattlement, and various peacebuilding projects in Asia, Europe, and Africa. Some area experts have realized that “the root cause of the current crisis lies much deeper. What has driven a wedge between the two fronts, is a fundamental philosophical disagreement over values, narratives and worldviews,” (20) as wrote Andreas Krieg in recent book “The Socio-Political Order and Security in the Arab World: From Regime Security to Public Security”.

The once brotherly weness [from we] and cozy tribal connections across most Gulf societies became entangled in a complex web of radicalized narratives through both traditional media and social media. According to Sara Cobb, a leading conflict practitioner of narrated conflict resolution, “radicalized narratives reduce the possibility for reflective judgements and obviate the possibility of a political moment; although this frame does not describe the narrative conditions (process and content) that could generate subjectification or reflective judgements, it does create a theoretical link between the nature of narrative and the critical dynamics in the public sphere.” (21) More than any other new media platform, Tweeter has served the new Gulf war of narratives per excellence. One Arab commentator captured how the media discourse has “polluted the Gulf sky” since June 5 2017, and “increased the cruelty and injustice of the political procedures that have harmed the peoples of the region.” (22) Consequently, the inner Gulf relations and the political and psychological burden of the 2014 and 2017 rifts burden have internationalized a sense of profound mistrust. Furthermore, certain stakeholders have embedded themselves in radical positions with a ‘zero-sum’ mentality.

In a previous piece, I wrote “a new cold war emerged behind the façade of the presumed Gulf unity, and media narratives became the gateway of the Quartet-Qatar dichotomy. In Washington, the Emirati ambassador, Yousef al-Otaiba, was ambitious in his anti-Qatar public relations campaign. He often reiterated UAE’s complaints about Qatar's maverick foreign policy, "What is true is Qatar's behavior. Funding, supporting, and enabling extremists from the Taliban to Hamas ... Inciting violence, encouraging radicalization, and undermining the stability of its neighbors." (23)

The derailment of conflict into escalation often leads to an exchange of negative narratives and damaging perceptions. It also generates mutual dark images as has been the case of the Gulf Crisis, between the disputing parties; and ultimately energizes the construction of ‘Other’ who was until recently a part of the collective ‘Self’ within the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). The widespread groupthink, echoed among the four capitals of the Quartet, has helped the stigmatization of the new ‘Other’, and opened the door for a variety of pretenses and justifications to target its status and reputation and destroy its economic, political, and diplomatic capabilities. Unfortunately, the dominance of self-centered realist and interest-oriented assumptions has led to the implosion of the GCC.

GCC: Collateral Damage?

The Gulf crisis stalemate coincided with the 39th anniversary of the Gulf Cooperation Council. Secretary-General Nayef Al Hajraf has expressed some skepticism since the GCC is facing unprecedented challenges, including the Qatar crisis and the fallout from the new Coronavirus. A number of regional and international observers have hinted Qatar could find itself outside the membership of the Gulf coalition. Andreas Krieg of King’s College in London noticed “Qataris are asking themselves what benefit a membership in the GCC still has, as the organisation has been usurped by Saudi Arabia and the UAE to coerce the smaller states into followership, while no initiative is being made to bring the Gulf Crisis to an end.” (24)

However, Qatar has refuted allegations that it is planning to withdraw from the GCC. Assistant Foreign Minister and Spokesperson for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Lolwah bint Rashid Mohammed Al Khater, stated June 5, 2020, “Reports claiming that Qatar is considering leaving the GCC are wholly incorrect and baseless.” She also mentioned “there is no wonder why the people of the GCC are doubting and questioning the GCC as an institution. Qatar hopes the GCC will once again be a platform of cooperation and coordination. An effective GCC is needed now more than ever, given the challenges facing our region.” (25)

Beyond Qatar’s membership, there is wider debate about the future of GCC. One school of thought argues it remains a much-needed strategic alliance among the Gulf six nations. Omani scholar Abdullah Baabood believes "This region is too small, the countries are too small to live alone. The challenges are huge. We are talking not just about traditional challenges and threats but we are also talking about ... economic, social, environmental challenges and pandemics and all of these, as well as security challenges, can only be confronted if the region can work together as one unit." (26) Still, another school of thought points to the weakening strategic value of the Council.

As Kristian Coates Ulrichsen concluded in his new book, “It is difficult to foresee what a ‘GCC 2.0’ might look like in practice, given its silence—as an institution—at every stage of the Gulf crisis, and especially after Sheikh Sabah of Kuwait and Sultan Qaboos of Oman eventually pass from the scene. If the institution survives, it may go the way of the Arab League and devolve into an ever more marginalized ‘talking shop’ removed from centers of power and authority.” (27)

![Late King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia put forward at the GCC summit in Dec. 2011 a proposal to transition the GCC from its cooperation phase to the union phase [Getty]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Photo%2010%20Late%20King%20Abdullah%20of%20Saudi%20Arabia%20put%20forward%20at%20the%20GCC%20summit%20in%20Dec.%202011%20a%20proposal%20to%20transition%20the%20GCC%20from%20its%20cooperation%20phase%20to%20the%20union%20phase%20%28Getty%29.jpg)

- Aljazeera News, “Qatar hopes new initiative to produce results in 3-year GCC rift”, Jun 6, 2020 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/06/qatar-hopes-initiative-produce-results-3-year-gcc-rift-200605190206936.html

- Aljazeera News, “Qatar hopes new initiative to produce results in 3-year GCC rift”, Jun 6, 2020 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/06/qatar-hopes-initiative-produce-results-3-year-gcc-rift-200605190206936.html

- Jacob Wirtschafter, “Qatar Embargo Shows Signs of Erosion”, the Voice of America, February 26, 2020 https://www.voanews.com/middle-east/qatar-embargo-shows-signs-erosion

- Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, Qatar and the Gulf Crisis”, Hurst and Company, 2020 p. 252

- William Zartman, “Ripeness: The Hurting Stalemate and Beyond”, in “International Conflict Resolution After the Cold War”, The National Academies Press. 2000

- William Zartman, “‘Ripeness’: the Importance of Timing in Negotiation and Conflict Resolution,” E-International relations, December 20, 2008, https://www.e-ir.info/2008/12/20/ripeness-the-importance-of-timing-in-negotiation-and-conflict-resolution/

- Morgan Palumbo and Jessica Draper, “How Saudis, Qataris and Emiratis took Washington”, Asia Times, June 10, 2020 https://asiatimes.com/2020/06/how-saudis-qataris-and-emiratis-took-washington/

- The Peninsula, “QC Chairman: 47,000 companies and 293 factories established since blockade”, June 4, 2020 https://www.thepeninsulaqatar.com/article/04/06/2020/QC-Chairman-47,000-companies-and-293-factories-established-since-blockade

- The Peninsula, “QC Chairman: 47,000 companies and 293 factories established since blockade”, June 4, 2020 https://www.thepeninsulaqatar.com/article/04/06/2020/QC-Chairman-47,000-companies-and-293-factories-established-since-blockade

- News Agencies, “US: List of Demands to Qatar should be Reasonable”, Aljazeera, June 21, 2017 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/06/list-demands-qatar-reasonable-170621182213569.html

- Aljazeera and News Agencies, “Arab states issue 13 demands to end Qatar-Gulf crisis”, Aljazeera, July 13, 2017 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/06/arab-states-issue-list-demands-qatar-crisis-170623022133024.html

- Taimur Khan, “Arab countries' six principles for Qatar 'a measure to restart the negotiation process”, the National, July 19, 2017 https://www.thenational.ae/world/gcc/arab-countries-six-principles-for-qatar-a-measure-to-restart-the-negotiation-process-1.610314

- Ibid,

- Ibid,

- aHabib Toumi, “Crisis resolution is up to Qatar, Al Jubeir says”, Gulf News, May 24, 2018 https://gulfnews.com/news/gulf/qatar/crisis-resolution-is-up-to-qatar-al-jubeir-says-1.2174195

- The National, “Saudi Arabia says Qatar continues to propagate hatred amid US efforts to resolve crisis”, February 4, 2018 https://www.thenational.ae/world/gcc/saudi-arabia-says-qatar-continues-to-propagate-hatred-amid-us-efforts-to-resolve-crisis-1.707513

- James Dorsey, “Gulf Media Wars Produce Losers, Not Winners”, Fair Observer, August 9, 2017 https://www.fairobserver.com/region/middle_east_north_africa/gulf-crisis-news-qatar-uae-saudi-arabia-arab-world-news-headlines-98712/

- Aljazeera News, “Qatar's Blockade in 2017, Day by Day Developments”, February 18, 2018, Aljazeera, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/10/qatar-crisis-developments-october-21-171022153053754.html

- Gardiner Harris, “State Dept. Lashes Out at Gulf Countries Over Qatar Embargo”, The New York Times, June 20, 2017 https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/20/world/middleeast/qatar-saudi-arabia-trump-tillerson.html

- Andreas Krieg, “The Gulf Rift – A War over Two Irreconcilable Narratives”, Defense in Depth, June 27, 2017 https://defenceindepth.co/2017/06/26/the-gulf-rift-a-war-over-two-irreconcilable-narratives/

- Sara Cobb, Speaking of Violence: The Politics and Poetics of Narrative in Conflict Resolution, Oxford University Press, 2013, p. 131

- aAhmed Al Omran, “Gulf media unleashes war of words with Qatar”, Financial Times, August 4, 2017 https://www.ft.com/content/36f8ceca-76d2-11e7-90c0-90a9d1bc9691

- Ishaan Tharoor, “The blockade of Qatar is failing”, The Washington Post, July 18, 2017 https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2017/07/18/the-blockade-of-qatar-is-failing/?utm_term=.214072c4d10e

- The Peninsula, “Reports of Qatar quitting GCC false”, May 30, 2020 https://www.thepeninsulaqatar.com/article/30/05/2020/Reports-of-Qatar-quitting-GCC-false

- Ibid,

- Aljazeera News, “Qatar hopes new initiative to produce results in 3-year GCC rift”, Jun 6, 2020 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/06/qatar-hopes-initiative-produce-results-3-year-gcc-rift-200605190206936.html

- Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, Qatar and the Gulf Crisis, Hurst and Company, 2020 p. 235