|

| [AlJazeera] |

|

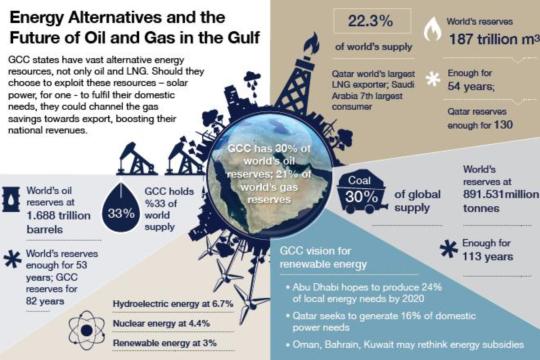

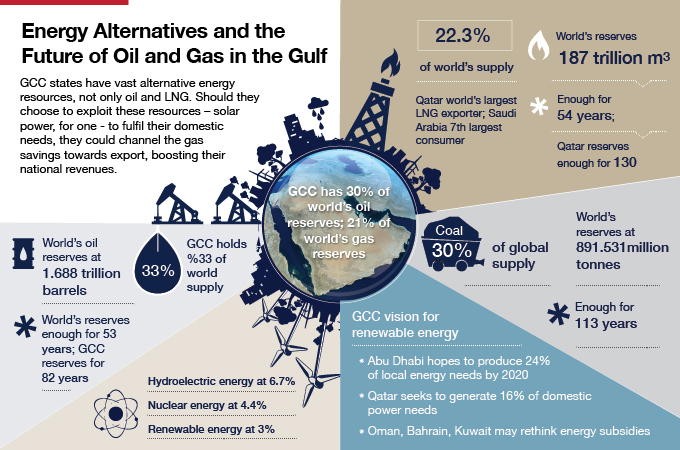

Abstract This chapter focuses on the importance of evaluating different energy sources in relation to optimising their usage. This is particularly relevant given increasing demands for electricity from local domestic and industrial users in the GCC countries. The GCC states have large reserves not only of crude oil and liquefied natural gas (LNG), but could also harness nuclear energy, as well as solar and wind power. The chapter concludes that the most important alternative power source for the GCC countries will be nuclear power. To this end, the building of nuclear power plants will be as essential as emphasising the peaceful use of this vital resource. The building of new plants will need to be achieved through contracting specialist companies and involving the relevant international bodies to ensure the safety of installations. |

Introduction

The GCC states’ need to harness alternative energy sources is not caused by a shortage of oil or gas. However, excessive reliance on these traditional but finite fossil fuels is seen as unwise, especially since alternative energy sources are within reach. In addition to hydroelectricity and nuclear power, renewable energy sources such as solar and wind power are beginning to seem increasingly feasible. While reservations about nuclear energy are common, given the sensitivities around the toxicity of nuclear waste and the manufacture of nuclear weapons, renewable energy sources such as solar and wind are freely available; and, unlike fossil fuels, the sun and wind are not facing imminent depletion.

If the GCC countries were to use alternative energies to meet their own electricity generation requirements, they would be able to export more of their gas and oil reserves, thus increasing state revenues. Using alternative energy sources to meet the increasing demand for electricity from domestic and industrial users also makes sense in terms of optimising energy usage.

Of course, the relative costs of oil and gas versus solar, wind and other technologies must be assessed. Historically, finding alternatives to oil seems to become a global priority whenever the price of black gold rises and remains high for significant periods of time. This chapter was written in the last quarter of 2014 when oil prices suddenly declined dramatically. Notwithstanding the massive drop in oil prices, the average price of oil remained above US$100 a barrel from 2011 to mid-2014, and may well rise to these levels again in the not too distant future.

The relative importance of different energy sources

The energy mix worldwide, and the relative importance of different energy resources, can be classified as follows: oil, coal, gas, hydropower, nuclear power, and renewable energy (see Table 1). The oil sector is undoubtedly essential, but this does not detract from the relative importance of coal or the potential growth of renewable energy sources. In addition to oil and gas, the GCC countries enjoy environmentally friendly energy resources, and have the potential to remain leaders in the provision of energy from various sources.

Table 1: Worldwide energy consumption in terms of energy sources in 2013

|

Energy source |

Percentage of total consumption |

|

Oil |

32.9 |

|

Coal |

30.0 |

|

Natural gas |

23.3 |

|

Hydroelectric power |

6.7 |

|

Nuclear power |

4.4 |

|

Renewable energy |

2.7 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

Source: BP (2014)

Oil

The oil sector, which includes both oil and gas, is the world’s primary energy resource source, providing about 56 per cent of the world’s energy at the beginning of 2014. More specifically, oil alone supplies about a third of the world’s energy needs, reflecting its great importance. The high demand for oil is primarily the result of our dependence on fuel-driven transportation and electricity in every area of our lives. In addition, oil and gas are essential raw materials used in the production of a vast range of commodities, from fertilisers to beauty products and building materials.

Oil reserves are still being discovered in different parts of the world. According to the Energy Report prepared by British Petroleum (BP), the available discovered global oil reserves are sufficient to last for around another fifty years. This estimate is based on current production and consumption levels (88 million barrels per day, or 31 billion barrels a year, compared with 1, 688 billion barrels of oil reserve volumes). At current production and consumption levels, oil reserves in the Middle East – including the GCC countries – are sufficient to last for about 82 years, which is far higher than the average, although the average rises to nearly 120 years in other regions, such as South America, particularly Venezuela.

New oil discoveries, particularly in South America, have increased the size of the world’s reserves from 1,041 billion barrels in 1993 to 1,334 billion barrels in 2003, and to 1,688 billion barrels in 2013. In fact, around 17.7 per cent and 15.8 per cent of global oil reserves are in Venezuela and Saudi Arabia respectively. However, due to different production capacities, the amount of oil produced by these two countries differs significantly. In 2013, for example, Saudi Arabia contributed about 13 per cent to global oil production while Venezuela contributed 3.3 per cent (see Table 2).

Table 2: Global reserves of oil and gas in 2013

|

Oil and gas-producing |

Percentage of discovered crude oil |

Percentage of world oil production |

Percentage of discovered natural gas |

Percentage of world gas production |

|

Venezuela |

17.7 |

3.3 |

3.0 |

1.0 |

|

Saudi Arabia |

15.8 |

13.1 |

4.4 |

3.0 |

|

Canada |

10.3 |

4.7 |

1.1 |

4.6 |

|

Iran |

9.3 |

4.0 |

18.2 |

4.9 |

|

Iraq |

8.9 |

3.7 |

1.9 |

– |

|

Kuwait |

6.0 |

3.7 |

1.0 |

– |

|

UAE |

5.8 |

4.0 |

3.3 |

1.6 |

|

Russia |

5.5 |

12.9 |

16.8 |

17.8 |

|

Libya |

2.9 |

2.7 |

– |

- |

|

USA |

2.2 |

10.8 |

5.0 |

20.5 |

|

Nigeria |

2.2 |

2.7 |

2.7 |

– |

|

Kazakhstan |

1.8 |

2.0 |

– |

– |

|

Qatar |

1.5 |

2.0 |

13.3 |

4.7 |

|

China |

1.1 |

5.0 |

1.8 |

3.4 |

|

Brazil |

0.9 |

2.7 |

– |

– |

|

Angola |

0.8 |

2.1 |

– |

– |

|

Algeria |

0.7 |

1.7 |

2.4 |

2.3 |

|

Mexico |

0.7 |

3.4 |

– |

1.7 |

|

Norway |

0.5 |

2.0 |

1.1 |

3.2 |

|

Oman |

0.3 |

1.1 |

– |

– |

|

Turkmenistan |

– |

– |

9.4 |

1.8 |

|

Australia |

– |

– |

2.0 |

– |

|

Indonesia |

– |

– |

1.6 |

2.1 |

|

Malaysia |

– |

– |

– |

2.0 |

|

Netherlands |

– |

– |

– |

2.0 |

|

United Kingdom |

– |

– |

– |

1.6 |

|

Others |

5.1 |

12.4 |

11.0 |

21.8 |

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

OPEC countries |

71.9 |

42.1 |

|

|

|

Former Soviet Union |

7.8 |

16.5 |

28.5 |

22.8 |

|

European Union |

0.4 |

1.7 |

0.8 |

4.9 |

Source: BP (2014).

Note: The only GCC country not listed here is Bahrain, which has no crude oil reserves and 0.1 per cent of global gas reserves.

Coal

Coal is currently the world’s second largest resource used for power generation. Evidence is that coal produced nearly 30 per cent of total global energy consumed in 2013. This proportion may increase in the future in light of the adoption of so-called ‘clean coal’ technologies. Of course, the cost advantages of the coal acquisition factor compared to some other sources cannot be denied, with this factor partly explains the continuing prevalence of coal use despite its inability to surpass oil consumption. It is true that coal reserves declined from 1,039,181 million tons in 1993 to 984,453 million tons in 2003, falling again to 891,531 million tons in 2013. However, the quantity of discovered coal is sufficient to ensure that, based on current production and consumption levels, there is enough to last for another 113 years.

Not surprisingly, China has the lion’s share of the world’s coal at 47 per cent. China’s reserves and production capacity are high, but so is the environmental impact of its coal production. Visitors to Beijing invariably notice high levels of smog, reflecting China’s relatively lax environmental policies. This situation is unlikely to last, and the Chinese authorities are already starting to introduce stricter controls. This might have implications for the future use of coal as an energy source in China.

By contrast, Germany has about 4.5 per cent of the world’s coal reserves, but its share of global coal production is about 1 per cent. This reflects Germany’s decision to cut back on the use of coal in line with environmental legislation introduced in the European Union. None of the GCC countries have significant coal reserves or production (see Table 3).

Table 3: Coal reserves and coal production in 2013

|

|

Percentage of discovered coal |

Percentage of coal production |

|

USA |

26.6 |

12.9 |

|

Russia |

17.6 |

4.3 |

|

China |

12.8 |

47.4 |

|

Australia |

8.6 |

6.9 |

|

India |

6.8 |

5.9 |

|

Germany |

4.5 |

1.1 |

|

Ukraine |

3.8 |

1.2 |

|

South Africa |

3.4 |

3.7 |

|

Indonesia |

3.1 |

6.7 |

|

Others |

12.8 |

8.9 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

Former Soviet Union |

25.6 |

7.1 |

|

European Union |

6.3 |

3.9 |

Source: BP (2014).

Gas

Gas comes third after oil and coal, in terms of global energy consumption. There is near-universal consensus that gas will be an essential energy source in the future. Huge discoveries of natural gas in South and North America, as well as China, combined with the growing phenomenon of shale gas in the US, are contributing to the uptake of gas for industrial use and electricity generation, to give just two examples.

Interestingly, reserves of discovered natural gas increased from 118 trillion cubic meters in 1993 to 157 trillion cubic meters in 2003, and to 187 trillion cubic meters in 2013. Discoveries are ongoing in many parts of the world, especially in Iran and Russia (see Table 2). Based on current production and consumption levels, the world has sufficient gas to last for another 54 years. However, natural gas reserves in the Middle East, especially Qatar, could last for 130 years, which is at present the highest projected duration period for their availability globally.

The top three countries in the world in terms of gas reserves are Iran, Russia and Qatar, but this might change given the ongoing shale gas discoveries. Unlike Qatar, Iran and Russia are generally considered unfriendly by many Western states. The West has also had several bad experiences with Russia over the issue of its gas supplies to Europe, especially during the winter periods when the demand for gas increases.

Hydroelectric power

Hydroelectric power contributes about 6.7 per cent to the global energy mix. Generally considered a renewable energy source, hydroelectric power is vulnerable to drought, and is not a viable option for the GCC countries.

Nuclear energy

In 2013, energy from nuclear power stations comprised about 4.4 per cent of global consumption. This was the lowest rate since 1984 due to Japan and other countries cutting back on nuclear power in the wake of the Fukushima disaster. As shown by the West’s stance on Iran’s nuclear programme, many people fear that the spread of nuclear technology could mean that it ends up being used for military purposes.

At the level of GCC countries, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has taken steps to secure nuclear energy, signing an agreement with South Korea and the relevant international supervisory bodies for the establishment of nuclear power plants. Given the country’s significant economic growth, and its efforts to strengthen its position in the global economy, the UAE’s leaders have realised that nuclear energy will be necessary to meet the growing domestic demand for electricity.

Renewable energy

Meeting increasing electricity demand in the GCC will mean doubling the electricity supply every decade, which, while expensive, is essential to sustain economic growth. Most of the GCC states aim to increasingly generate electricity from renewable sources so that they can export more of their crude oil and gas, thereby enhancing state revenues.

In addition, the GCC states are among the world’s fourteen worst countries in terms of carbon-dioxide emissions resulting from the consumption of fossil fuels, namely oil and gas.(1) Renewable energy sources have the potential to help the GCC states to both reduce emissions and contribute to protecting the environment. Also, renewable energy production costs are widely expected to decline in the coming years as the related technologies develop and economies of scale increase.

It is reassuring to know that the GCC countries have set some goals in relation to developing renewable energy sources by 2020. For example, Abu Dhabi, the capital of and second largest city in the UAE, aims to produce 24 per cent of its electricity via renewable sources by 2020, including from solar, wind and waste power. As of late 2014, 97 per cent of the UAE’s electricity was derived from gas.(2) Thus, the goals that have been set do seem reasonably realistic.

It is perhaps unsurprising that the Emirate of Abu Dhabi is promoting the use of renewable energy. The city already hosts the headquarters of the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), and has begun work on building Masdar City – a specialised settlement close to Abu Dhabi that aims to house around 45,000 people. The city aims to rely entirely on renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power, to meet its energy needs, and motor vehicles will not be allowed.(3) The city is being built by Masdar, a subsidiary of the immensely prosperous Mubadala Development Company.(4)

Similarly, the Emirate of Dubai, also in the UAE, plans to diversify its energy sources by 2030 in order to reduce its reliance on gas to just over 70 per cent of total consumption (see Table 4).

Table 4: Planned diversification of energy sources in Dubai by 2030

|

Energy source |

Percentage of energy supply |

|

Gas |

71 |

|

Nuclear |

12 |

|

Clean coal |

12 |

|

Solar |

5 |

Source: Dubai Electricity and Water Authority quoted in Al-Qallab (2014).

For its part, Qatar seeks to derive 16 per cent of its electricity from solar energy by 2018. This is considered the GCC countries’ most ambitious solar project so far.(5)

Affirming official interest in renewable energy, the GCC has hosted major international conferences on renewable energy. For example, the World Future Energy Summit 2013 was held in the UAE, after the country won the bid to host the IRENA headquarters in Abu Dhabi, while Greentech Media’s annual Solar Summit was held in Qatar in November 2014.

Analysts from organisations such as IRENA have explained that the GCC countries’ relatively tardy adoption of renewable energies (when compared with countries in Asia, Europe and North America) was linked to the state subsidies provided for the use of fossil fuels. In this regard, it is highly likely that Oman, Bahrain and perhaps Kuwait will again resort to subsidies in response to the sudden fall in oil prices.

In terms of energy consumption, research conducted by the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies revealed that Saudi Arabia is the sixth largest oil consumer in the world, and the seventh largest gas consumer. The study also estimated that, in the summer months, Saudi Arabia consumes up to 750 000 barrels per day, which is more than 10 per cent of its total crude oil exports.(6) Saudi Arabia exports more crude oil than any other country, but this consumption level involves massive energy wastage and high levels of pollution which mean losses to the state treasury and a need for the state to constantly pump money into infrastructure development to meet the demand.

The GCC’s oil and gas reserves

As shown in Table 1, the GCC countries have sufficient oil and gas reserves, with 30 per cent of the world’s total crude oil reserves and 21 per cent of the world’s natural gas. In addition to being the world’s top exporter of crude oil, Saudi Arabia became the world’s largest producer of black gold in 2013. This occurred when political instability in Libya, Syria and Yemen slowed down or stopped oil production in those countries, and Iran’s oil production was restricted because of the West’s response to Iran’s nuclear programme.

Qatar is distinct from other GCC countries because of its huge reserves of gas, and large LNG trains. Qatar is currently the world’s largest exporter of LNG, meeting approximately a third of the global demand for gas. This enhances the centrality of the GCC countries in the international energy sector, as Qatar exports LNG to Japan, South Korea, India, Spain, Britain and the United States, amongst other nations. In 1992, Japan’s Chubu Electric Power Company was the first country to seal a deal to import LNG from Qatar, with the first shipment of Qatari LNG delivered to the Japanese company in 1997, launching a new phase of growth and development for Qatar’s economy. According to BP, Qatar’s LNG production capacity reached about 77 million tons annually in 2013, and is capable of increasing further if the demand for LNG grows.

Other than Qatar, indications are that the GCC countries may be obliged to import gas in the coming years as one possible means of meeting growing domestic energy demands in their own countries. This is not necessarily because of problems with their oil-production capacities or dwindling reserves, but because they have long-term supply contracts with importing companies, as is standard practice in the energy sector, and they may not have sufficient capacity to meet the developmental needs of their own manufacturing and public sectors.(7)

Shale gas and oil

The exploitation of shale gas reserves in the United States –and to a lesser extent in China – may change the entire energy sector, including in the GCC countries. The extraction of shale gas is a controversial and risky process that requires sophisticated technology, but considerable progress has been made,(8) and some studies indicate that shale gas accounted for as much as 15 per cent of the global gas supply in 2013. This figure is expected to reach 50 per cent within the next twenty years, given the ever-increasing demand for electricity, as well as from the industrial sector.

As of 2014, shale gas comprised 40 per cent of total production of natural gas in the US. Shale oil reserves could reach nearly 345 billion barrels in the next few years, through the use of cutting-edge technology. This figure is close to the combined volume of oil reserves held by both Saudi Arabia and Venezuela (298 billion barrels and 265 billion barrels, respectively)(9)

It is widely believed that the availability of large quantities of US shale oil contributed to the decline in oil prices in the second half of 2014. Increased global energy supply and a falling demand for oil had – and is still having – an impact on oil prices. It is not clear whether the low oil prices will affect US shale oil production, but they may well do so given the high costs involved in shale oil extraction when compared to the price of crude oil. According to a report published by Al-Awasat in November 2014, shale-oil prices are more affected by low prices than those for conventional crude oil.

Conclusion

The GCC countries have high levels of alternative energy resources, not just crude oil and natural gas. While it’s true that the six member states do not have coal, the many months of sunshine that characterise the region’s climate are ideal for harvesting solar energy. Wind energy is also a viable option, especially in Saudi Arabia due to the vast open spaces. Regarding nuclear energy, the UAE is already pressing ahead with plans to build nuclear power stations.

The oil sector is expected to maintain its importance in the global economy given the ongoing demand for motor fuel, diesel and others petroleum products, and because practical and efficient alternatives are proving difficult to find.

Despite the growing importance of shale gas and oil in the United States and China, the GCC countries collectively remain one of the cornerstones of the global oil and gas sectors, in terms of discovered reserves and production.

_____________________________________________________

*Dr. Jassim Hussain is a researcher and economic analyst.

References

1. IRENA (International Renewable Energy Agency), Renewable Energy in the Gulf: Facts and Figures http://www.irena.org/DocumentDownloads/factsheet/Renewable%20Energy%20in%20the%20Gulf.pdf

2. Al-Qallab, Lamia (2014), UAE Aims to Produce 24% of its Electricity Needs from Clean Sources, 27 July [In Arabic] http://www.zawya.com/ar/story/ZAWYA20140727192313/

3. Gulf Center for Strategic Studies (2013), Renewable Energy Alternatives in the GCC Countries, [In Arabic] Akhbar Al-Khaleej, 13 August. http://www.akhbar-alkhaleej.com/12920/article_touch/40917.html

4. Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute (2014). The Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute estimated that Mubadala was worth nearly US$61 billion as of September 2014. This sum falls within the sovereign wealth of the UAE. For further details, see: Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute, (2014). Fund Rankings, November. http://www.swfinstitute.org/fund-rankings/

5. Shahan, Zachary (2013), Gulf Cooperation Council’s Renewable Energy Targets: Considerable or Weak? Green Energy Investing, 9 July. http://greenenergyinvesting.net/gulf-cooperation-councils-renewable-energy-targets-considerable-or-weak

6. The study Prospects for Renewable Energy in GCC States: Opportunities and the Need for Reform was cited in an article entitled Leniency in Energy Conservation Risks GCC Resources, which was published (in Arabic) by Al-Arabiya on 9 September 2014: http://www.alarabiya.net/ar/

7. Al-Hayat (2010) With 23% of global reserves, GCC countries other than Qatar may have to import gas to meet their needs, [In Arabic] 5 December: http://daharchives.alhayat.com/issue_archive/Hayat%20INT/2010/5/12/

8. Bazerkan, Mustafa (2013). The Shale Gas Revolution: Has America Achieved Independence From the Middle East? [In Arabic]: Al-Jazeera Center for Studies, 20 January. http://studies.aljazeera.net/issues/2013/01/2013120113758690180.htm

9. Scott, Mark (2014), Scouring the World for Shale-Based Energy: Shale Investments Could Reshape Global Market, New York Times, 17 June 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/18/business/energy-environment/