![[AP]](/sites/default/files/articles/2020-04/Photo-1-Cover-an-MH-60S-Sea-Hawk-helicopter-transports-cargo-from-the-fast-combat-support-ship-USNS-Arctic-to-the-Nimitz-class-aircraft-carrier-USS-Abraham-Lincoln-during-a-replenishment-at-sea-in-the-Arabian-Sea-%28AP%29.jpg)

Figuring out where the U.S.-Iran relationship is today requires that we go deeper than focusing on the immediate issues. This paper will show how the United States and Iran drifted over time into two wildly different strategic universes. The United States for much of its history with Iran has operated within the prism and strategic doctrine of the Cold War, even long after that conflict ended. Within such a doctrine, placing U.S. troops in the region deters Iran and economic sanctions weaken its capabilities to sow regional mischief. Iran’s lens on reality is very different, based on its centuries-old historical experience of having its sovereignty threatened by great powers. Lacking the ability to use conventional means to cope with greater powers directly, it has developed a “whole of region” approach since its 1979 revolution that fuses together ideology with unconventional military means.

This paper will also argue that once the Middle East regional order collapsed under the weight of the Arab Spring and the ensuing civil wars, Iran’s view of strategic reality gave it an edge that it lacked during earlier periods of its history. Within this changed regional order, the United States, which had built its doctrine around combatting a global threat from the Soviet Union, found itself flatfooted in dealing with a regional phenomenon like post-revolutionary Iran. Despite U.S. President Donald Trump’s attempt to cower Iran by withdrawing the United States from the JCPOA nuclear deal and re-imposing punishing sanctions, Iran has distinct strategic advantages in the region that the United States lacks. The United States can injure Iran, but it is unlikely to be able to compromise Iran’s regional influence. This paper will also argue that at the end of the Cold War, regional dynamics in the Middle East were such that the United States, at the height of its power, could at least claim that it was containing Iran. The focus will be on the evolution of two very different lenses on reality, and how regional transformation in the Middle East has altered which country has a proper claim on strategic advantage in the present day.

The United States and Iran are currently on a collision course, with no obvious exit ramp in sight. Even the Covid-19 tragedy, which is besieging Iran with particular ferocity, hasn’t dulled the hostilities.

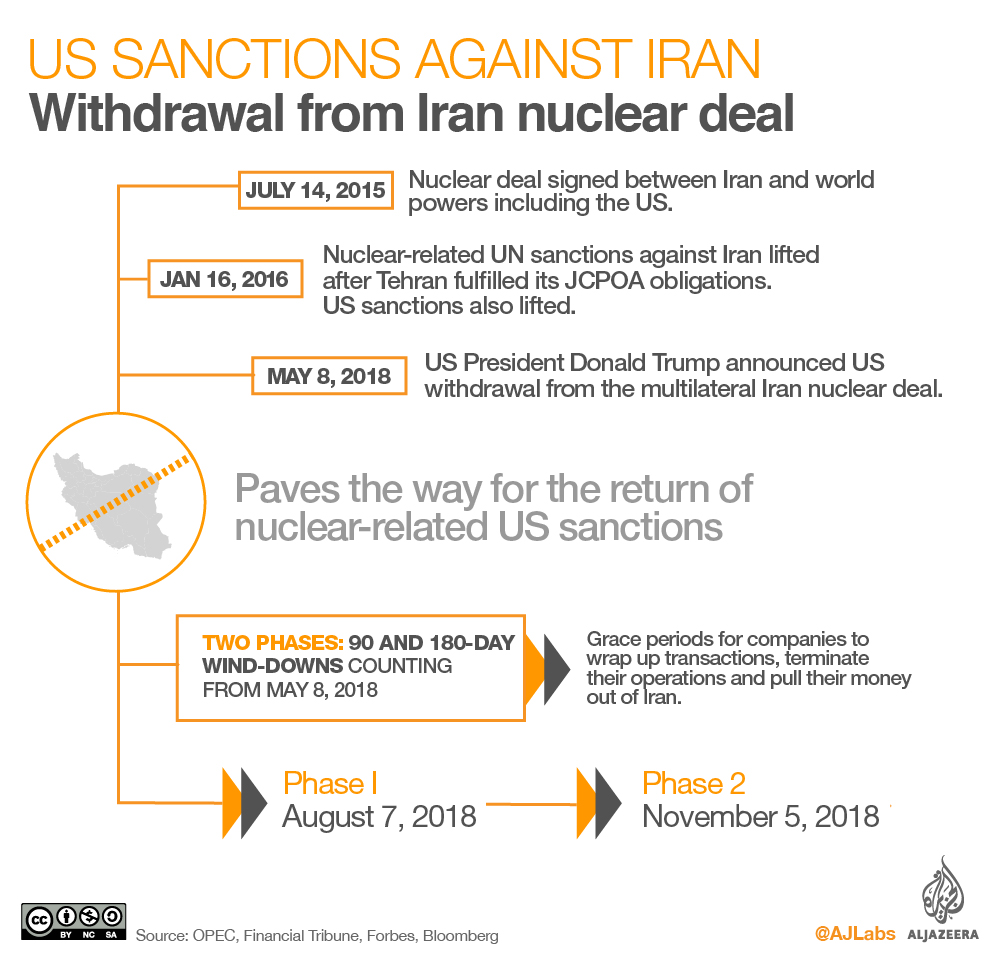

Contemplating the path this troubled relationship might take in the future requires an understanding of how we got to this dire point today. There are some obvious places to look for answers. Donald Trump renouncing the nuclear deal in May of 2018 could be considered ground zero. This act was accompanied by a resumption of U.S. sanctions, which a year later was followed by Iran’s provocative actions in the Persian Gulf. Other explanations less charitable to the Iranian view cite Iran’s missile program and regional activities as the source of the conflict. (1)

But while this analyst believes Trump’s renouncement of the nuclear deal was a reckless act of diplomatic malpractice, it is too convenient to heap all of the blame for the current state of U.S.-Iran relations on recent developments. Doing so misses the reality that Iran has bedeviled all U.S. Presidents since Jimmy Carter, whose administration had to contend with the Iranian Revolution in 1979 and the ensuing hostage crisis. President Obama was able to cobble together an international coalition to strike an historic nuclear deal with Iran. But this watershed moment was an anomaly when viewed against more than forty years of hostility.

Because of this pattern of a poisoned relationship, figuring out where we are today with Iran requires that we go deeper than focusing on the immediate issues.

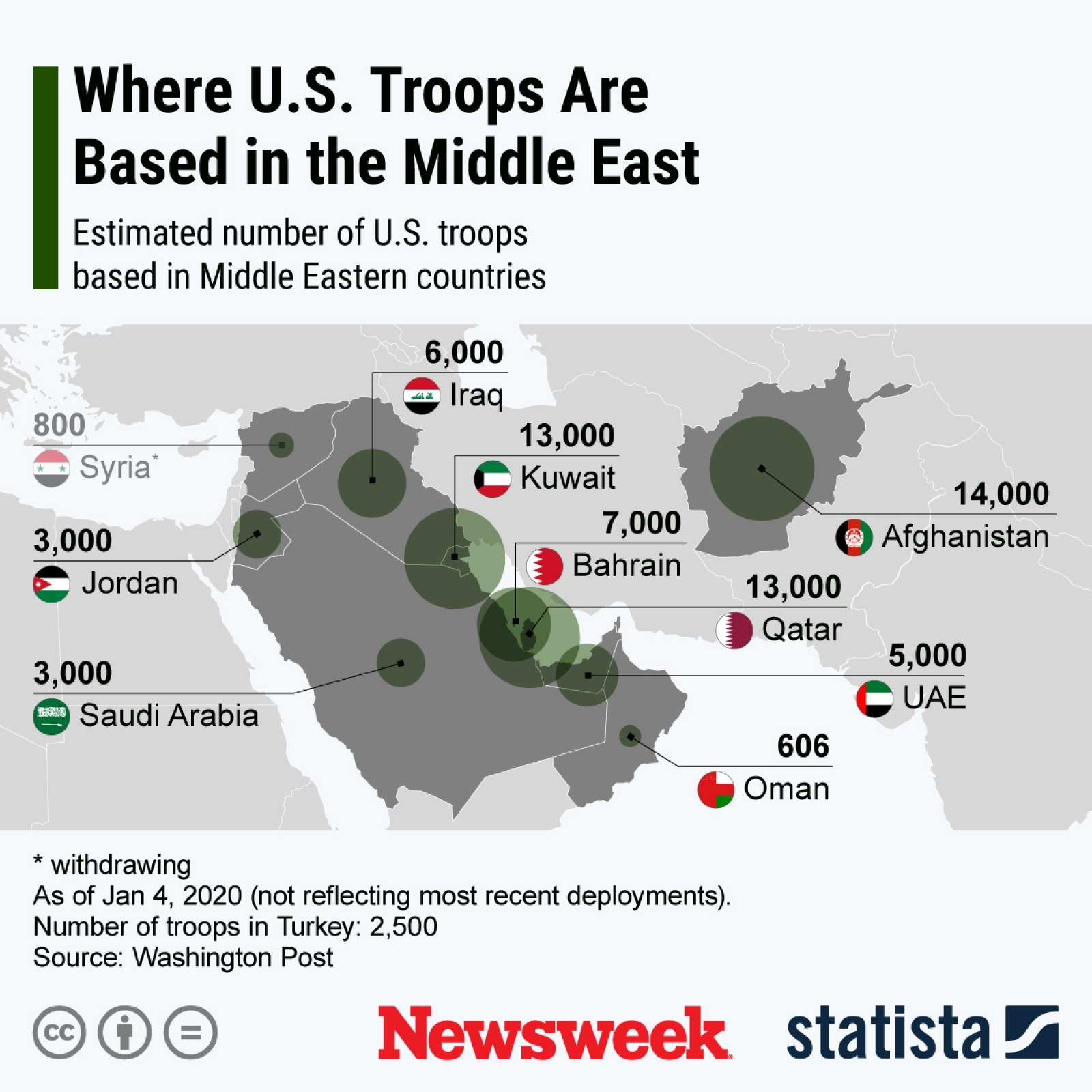

The remainder of this paper will show how the United States and Iran drifted over time into two wildly different strategic universes, and today operate within very different interpretations of reality, including but not limited to different views of history. The United States for much of its history with Iran has operated within the prism and strategic doctrine of the Cold War, even long after that conflict ended. Within that lens, Iran has replaced the Soviet Union as the primary source of instability in the Middle East, and therefore needs to be contained. Within such a doctrine, placing U.S. troops in the region deters Iran and economic sanctions weaken its capabilities to sow regional mischief.

Iran’s lens on reality is very different, based on its centuries-old historical experience of having its sovereignty threatened by great powers. Lacking the ability to use conventional means to cope with greater powers directly, it has developed a “whole of region” approach since its 1979 revolution that fuses together ideology with unconventional military means in an effort to resist the containment efforts of the United States, deter regime change schemes, as well as to project influence and power into the region.

Since the early 1990s, regional dynamics in the Middle East were such that the United States, at the height of its power, could at least claim that it was containing Iran. The United States, as the only remaining superpower, operated under the impression that it could impose a kind of Pax Americana on the Middle East. The Iran-Iraq war, after which Iran moved in a more pragmatic direction, and the first Gulf War, after which Iraq was contained, gave credence to this impression. While Iran was still projecting power into the region under the nose of the United States, it was done such as to not directly challenge U.S. containment efforts.

But once the regional order collapsed under the weight of the Arab Spring and the ensuing civil wars, Iran’s view of strategic reality gave it an edge that it lacked during earlier periods of its history. Not only did these regional transformations occur independent of the United States, it became clear that the U.S. strategic doctrine was poorly suited to the changed regional conditions. Within this changed regional order, the United States, which had built its doctrine around combatting a global threat from the Soviet Union, found itself flatfooted in dealing with a regional phenomenon like post-revolutionary Iran. The story that will be told in the following pages is about the evolution of two very different lenses on reality, and how regional transformation in the Middle East has altered which country has a proper claim on strategic advantage in the present day.

Genesis: The Origin of Two Different Views of Strategic Reality

Much of the enmity between the United States and Iran became deeply rooted during the Cold War. But to understand the source of the resentments between the two countries, we must start the story much earlier and on a more positive note.

-

Highwater Mark

Turning the clock back to 1909 we discover that the United States had a strong and positive brand in Iran. That was the year when a young idealistic American, Howard Baskerville, died defending constitutional rule in Iran, which had been won during the 1906 Constitutional Revolution. Baskerville came to Iran in 1907 on the heels of the revolution. He started teaching in the northern city of Tabriz, only to learn that Iran’s hard-won constitution was being trampled by Russia, Great Britain and Iranian royalist forces. Not content to be a mere bystander, he marshalled his students into a volunteer militia to preserve the hard-fought gains of the revolution. On April 19th, 1909, while out trying to break the siege by royalists, he was killed. He was mourned in Iran at the time as a martyr of the revolution and to this day is remembered as a hero. (2)

Another American, William Morgan Shuster, also contributed positively to the brand of the United States in Iran. Shuster arrived in Iran in 1911 at the request of the Iranian government to help get Iran’s public finances in order. From his post as Treasurer-General he railed against efforts by Great Britain and Russia to crush Iran’s sovereignty. Moscow and London opposed Shuster’s efforts to put Iran on a sounder financial footing, fearing this would increase its capacity to “stir up trouble” and resist foreign interference. (3) While official policy out of Washington toward Iran was more ambiguous, Shuster strengthened the image that because Iranian self-determination fit with American values, the United States would help ensure it. (4)

In 1919, at the end of World War I, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson rhetorically supported self-determination for Persia at the Versailles Peace conference, though he wasn’t willing to go so far as to alienate Great Britain. While his support was merely tepid, it reinforced the view among Iranians that the U.S. could be a hedge against the imperial designs of Great Britain and the Soviet Union. (5)

Finally, at the end of World War II the United States under President Harry Truman put diplomatic pressure on the Soviet Union to withdraw its troops from northern Iran, where they had halted on the way out of the country to support the Azeri and Kurdish separatist movements. The demarche Washington issued to Moscow to withdraw Soviet forces also burnished the American brand, even though it was based more on U.S. Cold War interests than any real concern for Iranian independence. (6) As a result of Baskerville, Shuster, Wilson, and Truman, the United States gained the reputation of being a champion of democracy and walking the talk of its values. It was seen as anti-imperial and a hedge against attempts by Russia and Great Britain to subjugate Iran to their interests. Even though official U.S. policy didn’t really match Iranian perceptions, and U.S. policymakers and the American public were often oblivious to how they were seen in Iran, the U.S. brand remained intact.

![US President Truman and Shah of Iran in the Oval Office 18 November 1949 [Truman Library]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Photo%206%20US%20President%20Truman%20and%20Shah%20of%20Iran%20in%20the%20Oval%20Office%2018%20November%201949%20%28Truman%20Library%29.jpg)

-

Low Water Mark: Betrayal

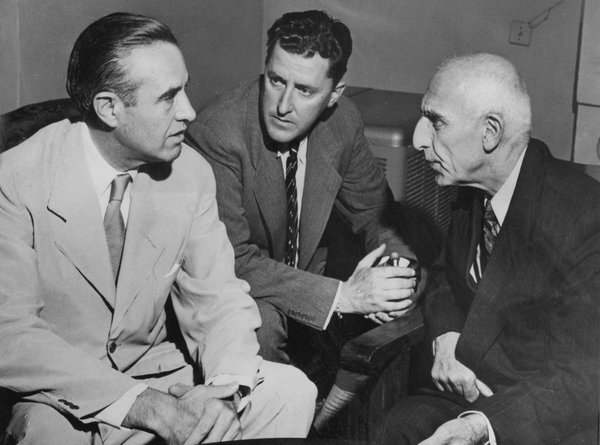

After this highwater mark in Iranian perceptions of Americans as champions of self-determination, for many Iranians the United States betrayed its own values and the Iranian populace in 1953 by supporting a coup against Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh. Because the United States had previously been viewed as a hedge against the imperial designs of both Russia and Great Britain, the perception of betrayal and disillusionment was that much more profound. In the eyes of many Iranians, instead of the United States standing up for Iran’s self-determination, their country had become a mere pawn for the United States in its struggle with the Soviet Union. It was during this period that the U.S. worldview and strategic doctrine congealed, and that an alternative view of reality started to percolate in Iran.

-

U.S. Strategic View

During the Cold War, the United States imagery about Iran centered on how it figured into the global rivalry with the Soviet Union. (7) In earlier times when U.S. vital interests weren’t at stake, it was easier for the United States to appear magnanimous in supporting values such as self-determination. But under an intense threat perception from the Soviet Union, the United States was forced to weigh American values such as self-determination against what it saw as its vital strategic interests of containing Moscow.

This tradeoff between values and vital interests created profound transmogrifications in U.S. policy. The United States in the 1950s saw the government of Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt as a potential asset against the Soviet Union, not in spite of, but because its government was authoritarian. Nasser suppressed the Communist party in Egypt and his tight control over the political system was thought to ensure that the Soviet Union couldn’t meddle in Egypt’s domestic politics. Though prospects of an alliance with Egypt fell apart over issues related to Israeli security, the U.S. dalliance with Nasser gives us a window onto how the United States subordinated concerns about the domestic behavior of leaders to the broader strategic concerns around combatting the Soviet threat. (8)

Paradoxically, the United States was more fearful of liberal nationalism in Iran than it was of authoritarian nationalism in Egypt. The belief was that the popularly chosen government of Mossadegh in Iran in 1953 was vulnerable to manipulation by Moscow through the Communist (Tudeh) party. Overturning it in 1953 was seen an acceptable price to pay to ensure that a hegemonic Soviet Union be denied a beachhead in Iran. (9) Policymakers rationalized their actions by seeing the overthrow of Mossadegh as serving both U.S. strategic interests and the welfare of the Iranian people. Deaf to the opposition building against the Shah of Iran after the coup, the United States was satisfied that the Shah’s façade of a secular parliamentary democracy and his economic reform measures, were enough to prevent domestic dissent. (10)

The worldview that justified the coup and that prevailed in Washington up until the Iranian revolution is instructive, as remnants of it survived the Cold War and are still with us today. It is a view that saw countries in the Middle East as derivative of the global struggle against the Soviet Union. There was little attention paid to regional dynamics, as the assumption was that the Middle East was organized along Cold War lines, with countries either aligned with the United States or the Soviet Union. (11) It was also very much a Manichean view of good versus evil, with U.S. allies falling into the former category and allies of the Soviet Union falling into the latter. (12) The instruments of power that were used to contain the Soviet Union were military and economic, and there was a strong bias toward the principles of deterrence and balance of power politics. (13) It was a global struggle between the United States and Soviet Union with countries in the Middle East fitting on either one side or the other of that divide.

-

Iranian Strategic View

From all appearances, the Shah of Iran and his government were in sync with the Cold War views held by U.S. policymakers. Massive financial support from the United States, and evidence that the communist Tudeh party had infiltrated the Shah’s security forces fortified that view. (14) Given the history of Russian imperial designs on Iran, it made sense that the U.S. saw the Shah as sharing its fear of a Soviet takeover. But what wasn’t evident to U.S. policymakers was that a new alternative narrative had started to percolate beneath the surface in Iran after the coup against Mossadegh. The alternative view was that the Shah’s suppression of dissent was encouraged and supported by the United States.

While this view that the United States was enabling the Shah’s repression gained currency among many opponents of the Shah, including the secular nationalists, a particular interpretation of reality was being propagated by Ayatollah Khomeini and his followers a decade or more before the 1979 revolution. Like the American view, Khomeini’s narrative was that politics were driven by a global struggle between the forces of good and evil. But his Manichean interpretation turned the American view on its head. Instead of seeing the primary struggle being between the United States and Soviet Union, he saw the divide being between oppressor and oppressed countries. Within this interpretation, both the United States and the Soviet Union fell into the oppressor category, with Muslim societies like Iran being the oppressed. (15) Regional allies of the superpowers played a part in this oppressive structure, doing the bidding of their respective patrons, and remaining calloused to the needs of their own Muslim societies.

![Militant students supporting Iran's Islamic Revolution stormed the US Embassy in Tehran and took scores of hostages Ultimately, 52 Americans were held for 444 days [Getty]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Photo%208%20Militant%20students%20supporting%20Iran%27s%20Islamic%20Revolution%20stormed%20the%20US%20Embassy%20in%20Tehran%20and%20took%20scores%20of%20hostages%20Ultimately%2C%2052%20Americans%20were%20held%20for%20444%20days%20%28Getty%29.jpg)

To Americans, this view of the United States and Soviet Union being joint hegemons seemed to be a delusional narrative, out of sync with the reality that the U.S.-Soviet conflict was the epic struggle. But Iranians who held this view weren’t completely blind to the rivalry between the United States and Soviet Union. They understood that the competition was real and intense, but nonetheless saw the superpowers as sharing a stake in a higher-level game of averting direct conflict by pushing their own conflict down to and meddling in developing regions like the Middle East. In other words, the view was that while they competed with one another, they jointly presided over a game that kept Muslim countries under the thumb of repressive governments.

While this worldview wasn’t mainstream in the 1950s and 1960s, it gained currency as Khomeini’s voice became louder and the country moved closer to the 1979 revolution. The view that the United States and the Soviet Union were collaborators in oppressing the Muslim masses may have sounded delusional to western sensibilities, it had some basis in Iran’s historical experience. In earlier times, Great Britain and Russia competed for influence in Iran, but despite this rivalry conspired to split up the country into zones of influence. Therefore, the notion that the Soviets and Americans could both compete but also have a common stake in preserving an oppressive status quo in the Middle East was not without historical parallel.

This Iranian view also had strategic implications. It was more regionally focused than the U.S. doctrine, as it was less state based and entailed a vision of the Muslim community (umma). It also encompassed threat perceptions at all levels. Global threats came from the United States and Soviet Union, regional threats from countries aligned with the superpowers, and local threats from autocrats like the Shah, empowered by their association with the superpowers.

Revolution and the Evolution of Strategic Doctrines

These different views of reality did not clash directly until the Iranian Revolution of 1979. Following this momentous event, the U.S. clung onto its Cold War views and the Khomeini worldview became the official one. And once these different views became enshrined in the strategic doctrines of the United States and Iran, the two countries were placed on a trajectory of conflict that hasn’t been broken for forty years, except for the very episodic and incremental interregnum during the Obama administration.

Iran

The Iranian world view which was expressed in depictions of the United States as the great Satan shocked most Americans who watched incredulously as Iranians marched in the street, shouting “Death to America”. While angry political refrains had started percolating after the 1953 overthrow of Mossadegh, the level of anger expressed after the 1979 revolution was new and jolting to most Americans.

The view held by Ayatollah Khomeini that the superpowers would collaborate to maintain a system of oppression against the Muslim masses was reinforced by real events after the revolution. Within this seemingly upside-down version of reality, it’s not just the superpowers themselves that pose a threat, but also their regional proxies. When Iraq invaded Iran in 1980, the prevailing view in Iran was that the United States was complicit as retaliation for the hostage crisis. (16) While there is little evidence to support the view that the United States directly prompted Saddam Hussein to invade Iran, once Iran gained the offensive in 1982, the United States did tilt towards Iraq, still a Soviet ally. This confirmed the idea that the Soviet Union and United States, while notional rivals, were on the same side of an oppressive game. (17)

Iran’s revolutionary worldview, which had been reinforced by the invasion from Iraq, combined with the historical experience of having been controlled by one or more outside powers, informed a strategic doctrine of security at home necessitating strategic depth in the region.

This notion of strategic depth, or as the Iranians like to call it “forward defense” had both ideological and realpolitik dimensions. Iran’s threat to export the revolution to neighboring countries, including Iraq, was part of an ideological doctrine. But the realpolitik dimension was that being disadvantaged when it came to conventional military might, Iran would develop an unconventional, asymmetric capability. Even while Iran was embroiled in war with Iraq, it helped establish Hezbollah in Lebanon, which it helped nourish through its relationship with Syria, the only Arab country that had stuck by Iran’s side. It also tried to exploit the vulnerabilities and legitimacy issues of the Gulf Arab monarchies. And it conducted a proxy war for influence with Saudi Arabia in Pakistan, and tried to mobilize majority Shi’i populations in Bahrain and Iraq, two countries that then were governed by minority Sunni governments.

The United States

In addition to the United States contending with an Iranian revolution that threatened to upend a regional political order that had served American interests for decades, in the 1980s it had to also cope with a split within its own foreign policy ranks. This division reflected two very different views of reality.

The first view, predominant in the State Department, was that Iran was a more immediate threat to U.S. interests in the Middle East than the Soviet Union. While officially the Soviet Union was still the “evil empire”, actions spoke louder than words. The tilt towards Iraq, a Soviet ally, during its war with Iran, and the reflagging of Kuwaiti ships in the Persian Gulf in 1987 as a deterrent against Iran, indicated a fear of Tehran undermining U.S. allies in the region. And it developed the view that like with the Soviet Union, containment was the best strategic doctrine for dealing with a menacing Iran.

The second view was manifest in the Iran-Contra affair in the mid-1980s which involved selling arms to Iran and was conducted in secret by a small cadre of folks from the White House, CIA and Department of Defense. This policy was seen by those policymakers as consistent with U.S. policy of supporting the Islamic mujahidin in Afghanistan against the Soviet Union. (18)

As rogue of an operation as Iran-Contra was, we shouldn’t overlook that it represented the view that the Soviet Union, and not Iran, remained the primary threat to U.S. interests, and that in fact Tehran could be an asset in containing that threat. What is striking is that this mainstream Cold War view, which had dominated U.S. policy for decades, now informed a rogue policy conducted sub rosa. The fact that this was a minority, marginal view within the U.S. government demonstrates the degree to which the Iranian revolution, and a fading Soviet Union, had shifted the mainstream view toward Iran replacing the Soviet Union as the primary threat to U.S. interests in the Middle East.

The two views operating simultaneously in the U.S. government represented a debate about whether the United States and Iran could find common cause, or whether Iran was the new enemy. Unfortunately that debate fell victim to the Iran-Contra scandal and was never had.

The view that survived was that Iran represented the primary threat to U.S. interests in the region. But the United States came to define its interests narrowly, through the lens of its allies, countries with which alliances had been forged as part of the U.S. strategy of containing the Soviet Union. But after the Cold War ended, those alliances with Israel, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Jordan, which had been established as means towards containing a global Soviet threat, had become ends in themselves. And containing Iran became official U.S. policy for protecting those allies. Moreover, the interests of those allies came to be seen as interchangeable with U.S. interests.

While the U.S. and Iranian views of reality were out of sync with each other, the question is which view was best suited for the regional environment at the time? The United States tilt towards Iraq during a war that bogged Iran down for eight years, may have vindicated containment as the right doctrine vis-à-vis Iran. But when we look at the emergence of Hezbollah as part of Iran’s handiwork in Lebanon, and the U.S. pulling up stakes from Lebanon after the 1983 bombing which killed 241 U.S. marines, the picture of Iran being contained doesn’t look so rosy.

What was clear was that Iran and the United States were playing two very different strategic games. While Washington was trying to use Cold War methods to contain Iran, Iran was building out its strategic depth doctrine through alliances with sub-state actors, a strategy must less susceptible to containment.

Clinton: The Ripening of Strategic Views and Doctrines

The Clinton era is a case study of how Iran and the United States operated in two different versions of strategic reality. The dual containment doctrine aimed at Iran and Iraq, announced shortly after President Clinton took office, laid bare the fact that the United States was essentially using tools from the Cold War to deal with post-Cold War challenges.

Iran, on the other hand, continued to operationalize its strategic doctrine of establishing relationships with sub-state actors. While Iran’s approach had an ideological dimension to it, it is also clear that Tehran’s motivation was to frustrate U.S. efforts to impose a Pax Americana that would preserve the regional status quo.

While the U.S. containment doctrine, and the Iranian doctrine of shifting to a containment-proof sub-state strategy, played out during the 1990s, neither country’s strategy was fully vindicated. The 1997 election of Mohammed Khatami as President of Iran muddied the strategic waters given his more accommodating stance towards the United States. But despite this, Iran and the United States didn’t deviate fundamentally from their strategies vis-à-vis each other.

Part of the reason for this was that the Middle East at the end of the Cold War had enough structure to accommodate the U.S. balance-of-power style worldview, but was porous enough to allow Iran to propagate its subterranean strategy of working through militias in the weaker areas of the region. In other words, there was enough ambiguity to the region to allow both strategic views to coexist without major conflict breaking out between the United States and Iran. This regional ambiguity strangely enough was reflected in the incoherence of the dual containment doctrine of the United States. Iraq and Iran were two very different challenges. (19)

![Former U.S. President Bill Clinton with his foreign policy team Madeline Albright, Sandy Berger, Aaron David Miller, and Robert Malley, Camp David 2000 [White House]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Photo%2012%20%20Former%20U.S.%20President%20Bill%20Clinton%20with%20his%20foreugn%20policy%20team%20Madeline%20Albright%2C%20%20Sandy%20Berger%2C%20Aaron%20David%20Miller%2C%20%20and%20Robert%20Malley%2C%20Camp%20David%202000%20%28White%20House%29.jpg)

Iraq had proven to be a regional aggressor using conventional military means against Iran and Kuwait. While it had launched brutal gas attacks against Iran (and Iraqi Kurds), for the most part Iraq used conventional military means. So, there was some logic to employing a containment model for that kind of challenge. And in fact, after Iraq was driven out of Kuwait in 1991, it was contained by the imposition of no-fly zones by the United States, UK and France, by sanctions, and by inspections by the United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM). But Iran didn’t really pose a conventional military challenge conducive to containment. To the degree it was exporting its revolution, it was doing so in the shadows using asymmetric means, not conventional military instruments of power. Its alliance with Hezbollah in Lebanon gave Iran the ability to project power into the Mediterranean, an effort augmented by an alliance with Syria. It also became a spoiler in U.S. efforts to try to resolve the Israel-Palestine issue. And it worked to undermine U.S. allies, like Saudi Arabia, that we were instruments in the U.S. dual containment toolbox.

While the United States was intent on making sure that Iran couldn’t successfully challenge American predominance in the region, containment was an imperfect vehicle for achieving this. (20) In a period where the United States was unchallenged as a superpower, its capacity to counter Iran’s very different strategic doctrine was limited. Iran was operating in the sub-state realm, using its revolutionary ideas to mobilize power, something that was impervious to containment. (21)

Moreover, Iran wasn’t alone in this subterranean strategy. Saudi Arabia too extended its power throughout the region, not through revolutionary ideology or militias, but rather by using petrodollars to build madrassas, establish foundations across the region and into the Indian subcontinent. This approach by Saudi Arabia is credited with the rise of many extremist organization throughout the Middle East. (22)

In sum, for most of the 1990s the regional order was porous enough with weak states like Lebanon to accommodate Iran’s strategic doctrine, but sufficiently intact to support the U.S. containment doctrine, if not with Iran, at least with Iraq. That would change with 9/11 and its aftermath and the revolts and civil wars of the Arab Spring era.

Trump: The Clash of Worldviews in a Shifting Middle East

The post-9/11 period in many ways turned history on its head. Paradoxically, at a moment when U.S. military power was unrivaled, the interventionist policies of the United States put in motion a regional transformation that disadvantaged the United States vis-à-vis Iran. The invasion of Iraq in 2003 gave a boost to an Iranian strategy that had been operating under the nose of U.S. officials since 1979. Since the revolution, Iran had worked toward its age-old dream of shaping its own foreign policy, rather than merely adapting to what for it had historically been an inhospitable international environment. The toppling of Iran’s nemesis, Saddam Hussein, by the United States handed the Islamic Republic a strategic windfall by giving it a perfect opportunity to advance its strategic depth and forward defense doctrines. (23) Plus the invasion reconfigured the regional distribution of power such that by the time the Arab Spring hit in 2010, the region was moving according to its own logic, far outside the control of the United States.

The chaos sowed by the U.S. invasion of Iraq played to the strength of the strategic doctrine Iran had been honing since the revolution, with its connections to sub-state actors like Hezbollah, Hamas and Islamic Jihad. While the United States may have intended through its foray into Iraq to send a menacing message to Tehran, at the end of the day it had the opposite effect. A weakened Iraq made containment an obsolete doctrine, giving Iran the ability to project power using its ties to the emerging Shi’i political leadership in the country, as well as to the Shi’i clergy. But, it was the Arab Spring and the civil wars that ensued in Syria, Iraq, Libya and Yemen that sparked the regional transformation that played to Iran’s strategic strengths and rendered the U.S. doctrine of containment anachronistic. The regional order collapsed under the weight of these civil wars and the emergence of ISIS. These events created both threat and opportunity for Iran. Tehran coordinated with Hezbollah to shore up the Assad regime, it formed militias in Iraq to fight ISIS, and it supported the Houthis in Yemen.

The regional disorder catalyzed by the civil wars left the United States flatfooted. Containment approaches are designed to prevent state-to-state aggression in systems where balance of power politics is the norm. But in a degraded state system, where civil war and state failure is the norm, containment as a doctrine is less effective.

Unvirtuous Cycle: Showdown between Trump and Iran

The Obama Administration seemed to understand that the U.S. ability to influence regional dynamics in a constructive way was limited. But Obama also grasped that the escalating battle between the United States and Iran on the nuclear issue contributed to instability in the Middle East, a region already fraught with conflict.

One of the bets of the nuclear deal of 2015 was to test the motivation of Iran’s strategic doctrine of forward defense. If Iran perceived reduced threat levels from the United States and the international community, would it feel less of an imperative to project power in the region? Would it eventually turn its regional involvement toward a more constructive role in ensuring a stable future for the Middle East? Or would it continue on its current path?

Since Trump walked away from the JCPOA in May of 2018, we will never know if Obama’s bet on the future of U.S.-Iran relations and the region would have paid off in the long run. The clash between the views held by the United States and Iran since the revolution finally came to a head after the nuclear deal was breached by Washington and sanctions were re-imposed. While the Trump Administration brazenly and even recklessly withdrew the United States from the nuclear deal, in many ways it was a reversion to the policies of previous administrations of trying to contain Iran by threatening military action and imposing economic sanctions.

But what had changed significantly in the years since the revolution was the nature of the Middle East. Starting with the disturbances of the Arab Spring, and the ensuing civil wars in the Arab world, the regional political order unraveled and there was a hollowing out of states in civil war, like Syria, Iraq, Libya and Yemen, as well as the region as a whole. (24)

There is a perfect storm afoot. Trump’s actions coupled with a regional order that has collapsed under the weight of four civil wars has made the current situation between the U.S. and Iran more incendiary. It has brought to a head the competition between two very different strategic views. While containment-style sanctions imposed by Trump have clearly impinged on Iran’s economy, and the United States would likely prevail in any conventional military conflict, the current regional environment plays to the strength of Iran’s doctrine of projecting influence and power through nonconventional means. So in a way, the United States and Iran are poised for a showdown, even though neither country really wants all-out war. The United States has the ability to hurt Iran economically, and militarily if it comes to that, but Iran has the capacity to continue to insinuate itself into Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and even Afghanistan, in ways that challenge U.S. interests.

This looming showdown has created a vicious cycle of conflict between the two countries. The Trump administration claims that one of the goals of its policy is to end Iran’s regional adventurism. But renouncing the nuclear deal and re-imposing sanctions has reinforced Iran’s view of history that its external environment is menacing. This in turn has strengthened the hard liners within the Revolutionary Guards that are pushing Teheran to further entrench its position in Syria, Yemen and Iraq. The Trump administration wedded to its strategic doctrine that Iran must and can be contained (and brought to the negotiating table) continues to double down further, including but not limited to assassinating the second most powerful leader in Iran, Major General Qassem Soleimani. U.S. actions continue to validate for Iran its perception of threat. But lacking the capability to resist U.S. efforts directly pushes Iran toward its indirect strategy of building out its “forward defense” doctrine in the civil war zones of the region. (25)

So while Iran is under pressure by the Trump administration, it is anything but contained. The Middle East is in a way like a punctured tire, where the more pressurize is applied, the more it leaks. (26) Similarly, the more the United States tries to pressure and contain Iran, the more Iran hunkers down in its positions in the civil war zones of the Middle East, sowing further instability, something that is counter to U.S. interests. Like a leaky tire, the more pressure placed on Iran, the more the region leaks instability.

To make matters worse, Iran isn’t the only regional power to be projecting power into the civil war zones. Saudi Arabia, the U.A.E., Qatar, Turkey and Israel are each involved in one or more of the civil wars. While the United States sees Iran as its central problem, in reality this is a power game being played out by all of the major regional actors, with dire implications for the Middle East. (27)

Conclusion: A Complex Escalation

The United States and Iran are on a collision course now because of the confluence of three major factors. The first is that the United States and Iran hold very different interpretations of reality. The United States operates within an anachronistic Cold War interpretation, where containment is the strategic doctrine by which state behavior can be altered. Moreover, the United States fails to see that it has a higher-level interest at stake, even more important than containing Iran, which is regional stability. Undermining this regional interest, it is playing to the worst instincts of Iran, but also allies Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Israel. Iran operates within a more regionally focused framework, seeing the Middle East as both a source of threat as well as opportunity. This is consistent with both its revolutionary ideology and its long history of coping with external interference.

The second factor is that while in the past the regional situation was elastic enough to accommodate the U.S. and Iranian strategic doctrines without a major military conflagration, today the region has transformed in a way that tilts the balance more towards Iran’s strategic doctrine. The Middle East has become a degraded state system that defies containment and allows Iran (along with other states) to project power through the countries at civil war.

The third factor is the continuation of the policies by the Trump administration. This has reinforced the worldview of Iranian officials least inclined toward accommodation, playing to their most hostile and unhelpful instincts. While the United States under Trump has successfully caused pain for Iran, this has only pushed Iran to further advance its strategy, which is likely to destabilize the region further, something that in a Covid-19 era neither the region nor the world can afford.

The strategy of the United States and other global power should be aimed at creating incentives and mechanisms to mitigate the rivalry between regional actors and the civil wars, not stoking them further. (28) Diplomacy needs to focus on developing some common ground on the need for regional security and stability. While the United States and Iran will likely remain out of sync in terms of their interpretations of history, they need to come together at least on some shared sense of the future. While unlikely with the current U.S. administration, and the current Supreme Leader of Iran, it should be a goal for the future.

- See as an example of this line of thinking. Ruel Marc Gerecht, “The Iran Deal is Strategically and Morally Absurd”, The Atlantic, May 4th, 2018

- See Dean Andromidas, “When Americans Fought for Iran’s Sovereignty”, EIR History (Volume 36, Number 32, August 21, 2009) and Stephen Kinzer, “Iran’s Favorite Midwesterner: How the long-forgotten Story of a Minister’s from Nebraska could Remind Tehran and Washington of a Common Heritage”, Politico Magazine (July 18th, 2015)

- Dean Andromidas, “When Americans Fought for Iran’s Sovereignty”, EIR History (Volume 36, Number 32, August 21, 2009)

- See Richard W. Cottam, Iran and the United States: A Cold War Case Study, (University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, PA) pages 19-55 for an analysis of this period, where U.S. brand was strong in Iran, but U.S. policy was more ambiguous.

- See Kamyar Ghaneabassiri, “U.S. Foreign Policy and Persia: 1856-1921, Iranian Studies (Vol 1/3, Winter-Summer 2002, pp. 145-175)

- Cottam, Iran and the United States, pp 55-110 for an analysis of the crisis in Azerbaijan.

- Richard W. Cottam, Foreign Policy Motivation: A General Theory and Case Study, (University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, 1977, p. 10. Also, see Stephen Benedict, “Cognitive Style and Foreign Policy: Margaret Thatcher's Black-and-White Thinking”, International Political Science Review, Vol. 30, No. 1 (Jan., 2009), pp. 33-48, and Thomas S. Mowle, “Worldviews in Foreign Policy: Realism, Liberalism, and External Conflict”, Political Psychology, Vol. 24, No. 3 (Sep., 2003), pp. 561-592

- Henry William Brands, Jr., “What Eisenhower and Dulles Saw in Nasser: Personalities and Interests in U.S.-Egyptian Relations” Middle East Policy Council (Volume IV, Summer 1986, Number 2)

- See Stephen Kinzer, All the Shah’s Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror (Wiley, New York) 2008 for a good journalistic account of the coup.

- Cottam, Iran and the United States, p. 122.

- Ross Harrison, “U.S. Foreign Policy Towards the Middle East: Pumping Air into a Punctured Tire”, Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, March 7th, 2019

- Stephen Benedict, “Cognitive Style and Foreign Policy: Margaret Thatcher's Black-and-White Thinking”, International Political Science Review, Vol. 30, No. 1 (Jan., 2009), pp. 33-48. Also, see Richard W. Cottam, Foreign Policy Motivation: A General Theory and Case Study (University of Pittsburgh Press: 1977) chapter 4.

- Hans J. Morgenthau, Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power 6th Edition (McGraw Hill: 1985)

- Cottam, Iran and the United States, p. 115

- See Shireen T. Hunter, Iran and the World: Continuity in a Revolutionary Decade (Indiana University Press: Bloomington, Indiana, 1990) pages 36-46 for an excellent analysis of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary worldview.

- Shahram Chubin and Charles Tripp Iran and Iraq at War (Westview Press, Boulder, CO: 1991) p. 206

- Richard W. Cottam, “U.S. Policy in the Middle East” in Hooshang Amirahmadi (editor), The United States and the Middle East: A Search for New Perspectives (State University of New York Press, Albany, NY: 1993) p. 49. Also, see Michael Sterner “The Persian Gulf: The Iran-Iraq War”, Foreign Affairs, Fall 1984.

- Richard W. Cottam, Iran and the United States, pp. 251-2.

- F. Gregory Gause III, “The Illogic of Dual Containment” Foreign Affairs March/April 1994

- For the thinking of the Clinton Administration at the time, see the statement by Martin Indyk, who was the architect of the dual containment policy in, Martin Indyk “The Clinton Administration’s Approach to the Middle East”, Soref Symposium Conference Report, 1993, The Washington Institute for Near East Policy

- See Kayhan Barzegar and Abdolrasool Divsallar, “Political Rationality in Iranian Foreign Policy” The Washington Quarterly, Spring 2017

- For the best portrayal of this proxy dynamic between Iran and Saudi Arabia in the decades following the Iranian Revolution, see Kim Ghattas, Black Wave: Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the Forty-Year Rivalry That Unraveled Culture, Religion, and Collective Memory in the Middle East, (Henry Holt and Co, New York) 2020

- Amr Yossef, “Upgrading Iran’s Military Doctrine: An Offensive Forward Defense”, Middle East Institute, December 10th, 2019.

- aSee Paul Salem and Ross Harrison (eds), Escaping the Conflict Trap: Toward Ending Civil Wars in the Middle East (MEI Press, 2019)

- Harrison, “Pumping Air into a Punctured Tire”

- Harrison, “Pumping Air into a Punctured Tire”

- Salem and Harrison (eds), Escaping the Conflict Trap

- See Mahsa Rouhi, “Iran and America: the perverse consequences of maximum pressure”, Survival (editor’s blog), March 10th, 2020