Two main political coalitions will face off in the Turkish presidential and parliamentary elections, scheduled for 14 May 2023. On one side is the People’s Alliance, which brings together the governing Justice and Development Party (AKP) and the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP). On the opposite side is the Nation Alliance, made up of the Republican People’s Party (CHP), the historic Kemalist party, and the nationalist Good Party, which split from the MHP five years ago, as well as four small, generally conservative parties. Bound together only by member parties’ hostility to President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the Nation Alliance has coalesced around a pledge to restore a parliamentary system of government within two years if it wins.

Over the past two decades, predicting electoral outcomes in the six or seven weeks running up to the poll has been relatively simple, but Turkey’s political landscape has shifted in the past year in a way that makes assessing the fortunes of the two largest coalitions more complex.

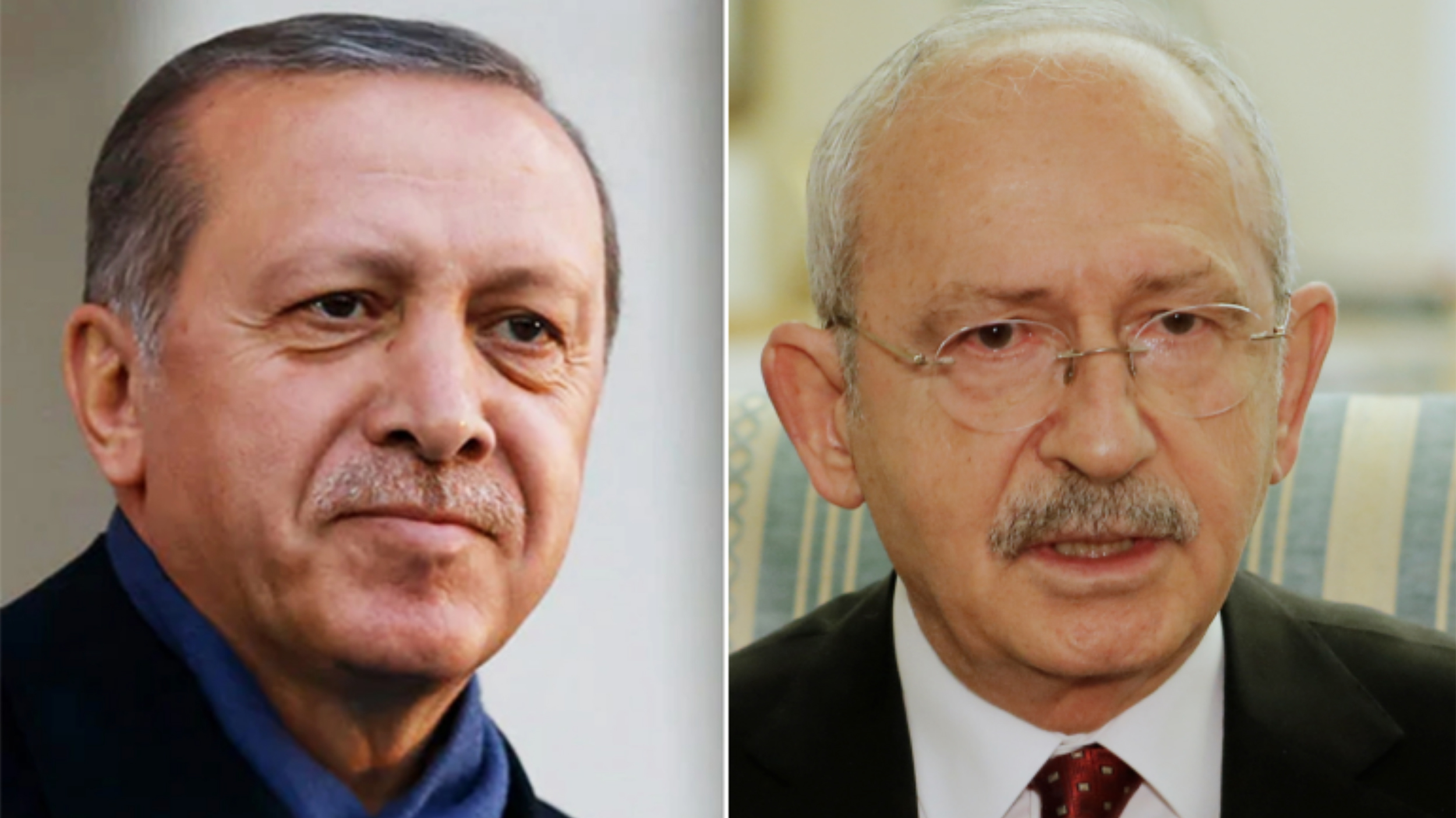

CHP head Kemal Kilicdaroglu has lately emerged as the joint presidential candidate for the Nation Alliance. While he is a well-known political figure, he has no record of achievements to tout to voters who may wonder if he is up to the domestic and diplomatic challenges facing Turkey. The ideological diversity of his coalition may also put a damper on his presidential aspirations. To win the backing of his coalition, Kilicdaroglu pledged to appoint a vice-president from each of the five member parties, promising to actively involve them in strategic decisions and policies. Given the country’s previous bad experience with coalition governments, this unwieldy alliance may give the electorate pause. The Kurdish-oriented Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP)—projected to win some 11 percent of the parliamentary vote—is expected to back Kilicdaroglu as well. While the additional support is welcome, it may drive off voters from Kilicdaroglu’s own coalition, who see the HDP as a threat to the Turkish state. The fact that Kilicdaroglu belongs to Turkey’s Alawite minority may be another handicap when it comes to conservative and Islamist voters.

President Erdogan faces obstacles to victory as well. Having been in power since 2003, he can point to a long list of concrete accomplishments, domestically and on the international stage; but after two decades, many voters may feel it is time for a change. The economic crises that have buffeted Turkey since 2018 have led some to believe that the economic miracle presided over by Erdogan and the AKP has reached the end of the road, and they may be bolstered in this belief by intimations from abroad that Western financial institutions and investors will become more supportive of the Turkish economy if Erdogan is ousted.

On the parliamentary side, the first step for both coalitions is to prepare their electoral lists. This is by no means an easy task, especially for the more factious Nation Alliance, which must decide if it will run a joint list of candidates and what kind of representation its small parties will get. (Parties must claim at least seven percent of the vote to enter parliament). The stakes for both coalitions are high. Even if Erdogan wins the presidency, it will be difficult for him to govern if the People’s Alliance does not maintain its parliamentary majority. Its chances depend mainly on how satisfied the electorate is with the government’s economic performance and its response to the February earthquake and its aftermath.

The Nation Alliance faces more of an uphill battle. Making good on its promise to move to an “enhanced parliamentary system” requires a constitutional amendment, which means it needs to win a two-thirds majority in parliament—a difficult proposition. Even winning a simple majority will depend on the coalition’s ability to move beyond its criticism of Erdogan and the AKP to present an achievable vision for Turkey’s future.

The upcoming presidential and parliamentary elections are likely among the most important in decades. From the founding of the republic until 2002, Turkey was led by a single ruling class. But by holding power for two decades, the AKP has fundamentally changed Turkish politics and introduced a new ruling class from a different social and political background, with far-reaching impacts across the economy, culture and education.

If Erdogan and the AKP lose the election, the old class will return to power in a spirit of vengeance, armed with the legal and coercive tools of the state, which even Kilicdaroglu and his allies may be unable to restrain. If the People’s Alliance is victorious, it will have five full years to groom capable heirs who can preserve the gains made by the conservative Turkish majority in the past two decades and faithfully follow in the AKP’s footsteps.

*This is a summary of a policy brief originally written in Arabic, available here.