For the last decade, since the eruption of the Arab revolutions, conflicts between regional powers in the Middle East have claimed the lives of tens of thousands of people and stymied opportunities for development and reform. Rivalries between shifting power axes have left virtually no country unscathed, fuelling civil wars in Libya, Syria and Yemen and polarising national politics across the Arab world. The regional Arab and Gulf order has been destabilised and fragmented, as the influence of conventional leading powers like Egypt and Saudi Arabia has been eroded and Turkey and Iran have stepped into the breach.

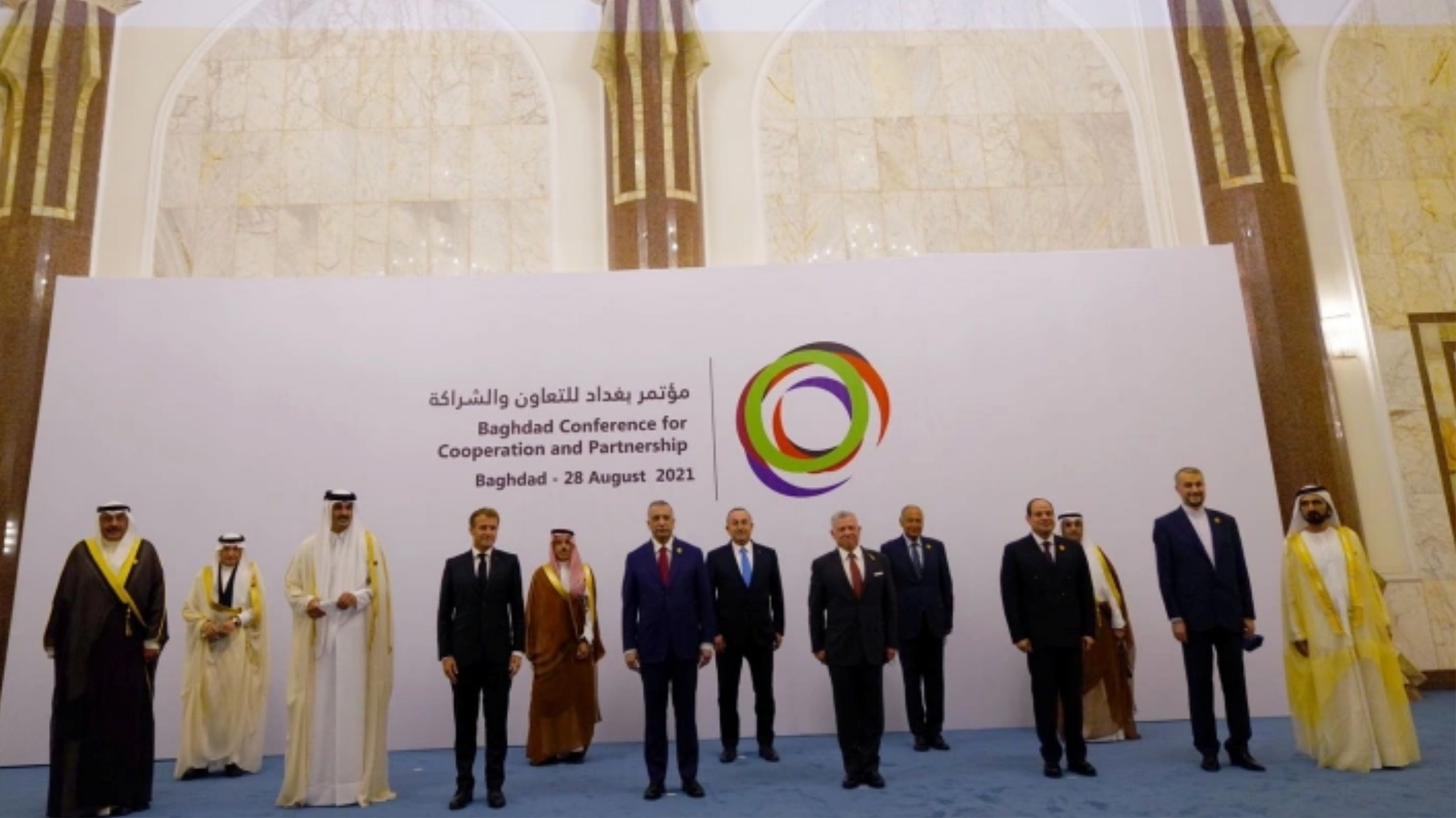

Yet, suddenly over the last year, a palpable shift began to occur. The vicious rhetoric traded by rival medias and the demonization of opponents declined or disappeared entirely, and bilateral ties were restored between countries that only recently seemed to be on the brink of open war. Both Saudi Arabia and Egypt mended fences with Qatar, lifting the blockade and moving toward a full normalisation of diplomatic relations. Egypt and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) took steps to reconcile with Turkey and restore diplomatic and commercial ties. Even Saudi Arabia and Iran—long-standing, bitter rivals—have taken tentative, preliminary steps toward a rapprochement, meeting for an unofficial dialogue under Iraqi aegis.

The question is why now, and all at once?

There are country-specific reasons for bilateral reconciliations of course. Egyptian-Turkish rapprochement, for example, was set in motion by Turkey’s active intervention in Libya and the defeat of Egypt’s ally, General Khalifa Haftar, in 2020, and given additional impetus by other issues—the activities of the Egyptian opposition in Turkey, or major Turkish investments in Egypt—that make normalising ties more attractive for both parties than continued hostility. The Saudi-Iranian thaw is governed by a similar logic, with the impasse in Yemen providing the starting point for exploring a detente.

But the timing of this new conciliatory trend appears to be determined less by bilateral factors and a sudden realisation of the high cost of combative policies than by broader international shifts—specifically, President Donald Trump’s electoral loss and Joe Biden’s victory.

The Trump administration gave political and moral (and at times, military) sanction to the policies of many allied Arab states. Even if its support was not always proactive or effective, these states understood that they would face no US opposition or pressure to change course. The Biden administration, however, immediately made clear its displeasure with the conduct of its regional allies and the human rights situation. It has also proved indifferent to the concerns of its Arab allies, making unilateral decisions on matters of regional importance without consulting them, most significantly the withdrawal from Afghanistan and the resumption of US-Iranian talks to revive the nuclear deal.

While the regional thaw is promising and the de-escalation of tensions certainly welcome, the main problem is that thus far it has not resulted in any concrete, substantive progress on the issues driving conflicts. For example, despite better relations between the regional powers active in Libya— Turkey, Egypt and the UAE—the country remains as polarised as ever; and Haftar and his national allies show no readiness to unite the country or allow for peaceful elections in December. Similarly, despite Iranian-Saudi dialogue, Houthis continue to strike Saudi targets and the Saudi-led alliance continues to shell Houthi positions in Yemen. Nor has talk of a possible accommodation had a tangible impact on the political situation in Lebanon or Iraq, where the Saudi-Iranian rivalry has had such pernicious consequences.

No less important, the trend toward reconciliation has been of little benefit to the region’s peoples themselves, who have paid most dearly for a decade of conflict. Regimes that quelled popular uprisings with violence and the support of regional allies are growing more violent, while civil wars fuelled by regional disputes continue to rage. Even Tunisia—widely touted as an exemplar of post-revolutionary democratisation—has suffered a setback, with the president subverting the constitutional order with explicit regional backing.

Swift reconciliations initiated by regimes with the purpose of cutting their losses and shoring up their own sources of power are not enough to establish enduring stability and a genuinely cooperative regional order. This requires a rational, pragmatic approach that grapples with the issues underlying the conflicts and makes a clear-eyed assessment of the specific interests of each major actor.

*This is a summary of a policy brief originally written in Arabic, available here.