Turkey held both presidential and parliamentary elections on 14 May 2023, the second poll since the country transitioned to a presidential system.

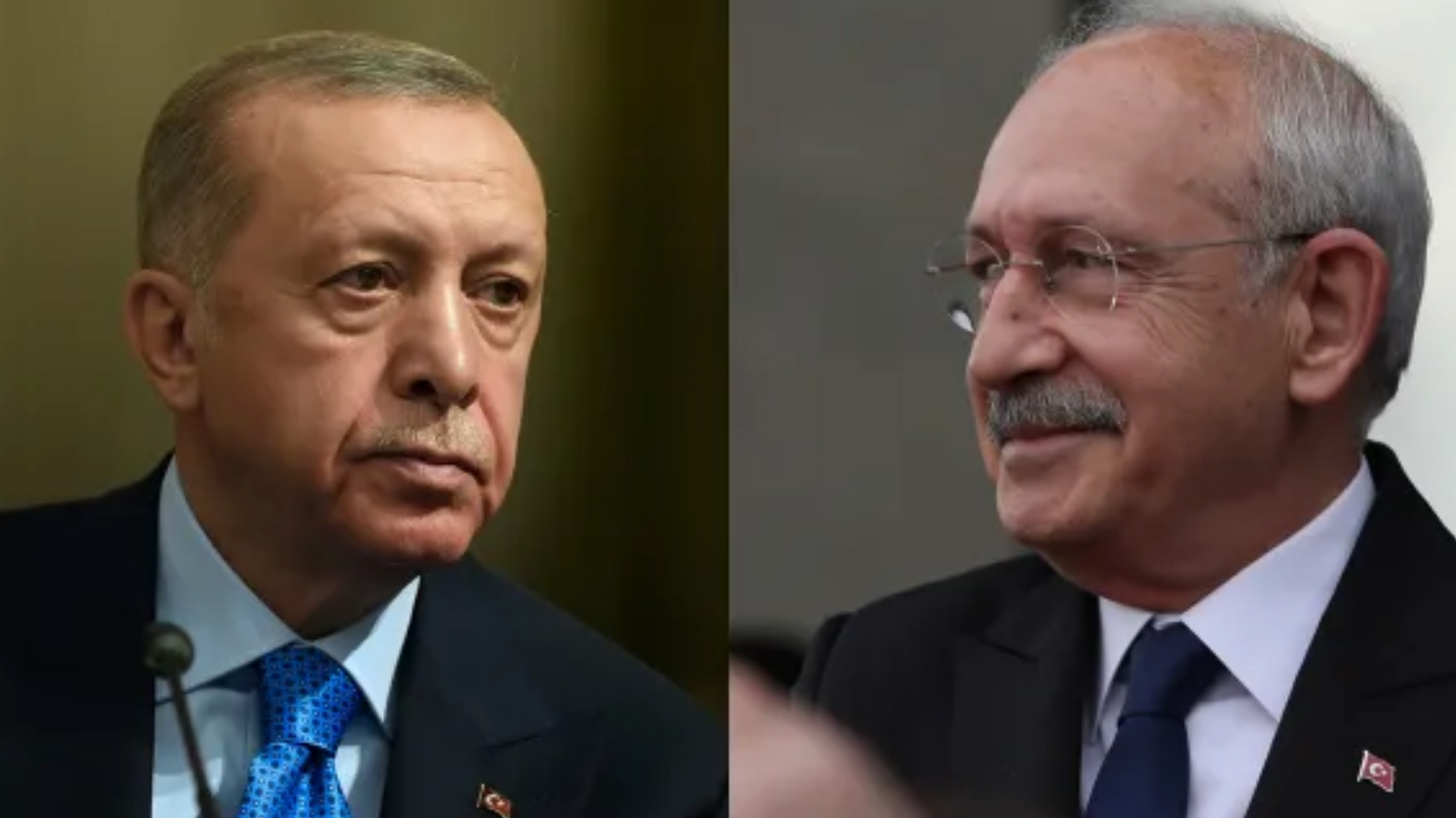

The presidential race saw President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, head of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) and leader of the country since 2003, face off against Kemal Kilicdaroglu, leader of the Republican People’s Party (CHP) and the opposition. Sinan Ogan stood as the candidate for the far-right Ancestral Alliance. Although he had little chance of victory, it was clear from the outset that he could siphon off enough votes to force a runoff, denying Erdogan or Kilicdaroglu the necessary 50 percent of the vote in the first round.

Two major coalitions competed in parliamentary elections. The first, the People’s Alliance, includes the AKP, which has governed the country since 2002, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), and a handful of smaller parties. The second coalition, the Nation Alliance, consists of the CHP, the secular Kemalist party that led the country for a quarter of a century, and the Good Party, a nationalist offshoot of the MHP, as well as a few other small parties, none of which were expected to win even 1 percent of the vote. Given their marginal weight, their presence in the Nation Alliance was not meant to bolster the main parties’ parliamentary fortunes, but rather to help mobilise broad support behind a single opposition presidential candidate with a chance of beating Erdogan.

The results surprised all parties and observers. There was a consensus in Turkish political circles, even among the AKP, that the People’s Alliance would lose its parliamentary majority to the Nation Alliance and the Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP). Instead, it returned to parliament with a comfortable majority, winning 322 of the chamber’s 600 seats. Nevertheless, the AKP itself continues to lose ground and is no longer able to win a parliamentary majority on its own, as it did from 2002 to 2015. This should push the party leadership to seriously reconsider its leadership and policy stances.

On the other side, the CHP increased its vote share from 2018, but still won barely 25 percent of the votes. In fact, it actually lost seats in the parliament since the deal between Kilicdaroglu and the smaller conservative parties of the Nation Alliance gave the latter 34 seats. The Good Party’s share also fell to about 9 percent of the vote, three or four points lower than projected.

The HDP fell short of its share of the vote in the 2018 election as well, taking less than 10 percent of ballots.

In the presidential race, the major surprise was the gap between Erdogan and Kilicdaroglu, with the former taking some 49.5 percent of the vote against barely 45 percent for Kilicdaroglu, about equal to the share of all three of Erdogan’s competitors in the 2018 election. The race was not nearly as close as most opinion polls and observers had predicted. Kilicdaroglu likely lost a tangible segment of the conservative Kurdish vote as well as a significant percentage of Good Party voters who opposed his alliance with nationalist Kurds. Erdogan failed to match his performance of 2018, when he won in the first round, likely due to his problem with the Kurdish vote, particularly conservative Kurds, who used to be reliable AKP voters, as well as his loss of some of the nationalist vote to Ogan.

Nevertheless, the overall results of these elections clearly indicate that the majority of the Turkish people wish to stay the course of the past two decades of AKP governance, despite the economic difficulties of the past two years. The opposition alliance, though unprecedented, was unable to convince Turkish voters that it represented a serious alternative that could be trusted to lead the country in the midst of an economic crisis and regional turmoil.

But Erdogan’s victory in the second round on 28 May is not guaranteed. Both presidential candidates must motivate their voters to turn out for the runoff. Moreover, it is uncertain how Ogan’s voters will break in the second round, whether for Erdogan or Kilicdaroglu or neither. In addition, voter turnout likely fell two points short of the projected 89 percent, with most of those who abstained withholding their vote from Erdogan in particular, for economic reasons. Erdogan will thus need to convince these non-voters, especially in Istanbul—the most hard-hit by the economic crisis—that he will focus on the economy and is worthier of their trust than Kilicdaroglu. Some observers believe that Erdogan can handily win the second round if he names a few key members of his coming government with the stature and name-recognition to gain the confidence of a large segment of the public.

*This is a summary of a policy brief originally written in Arabic, available here.