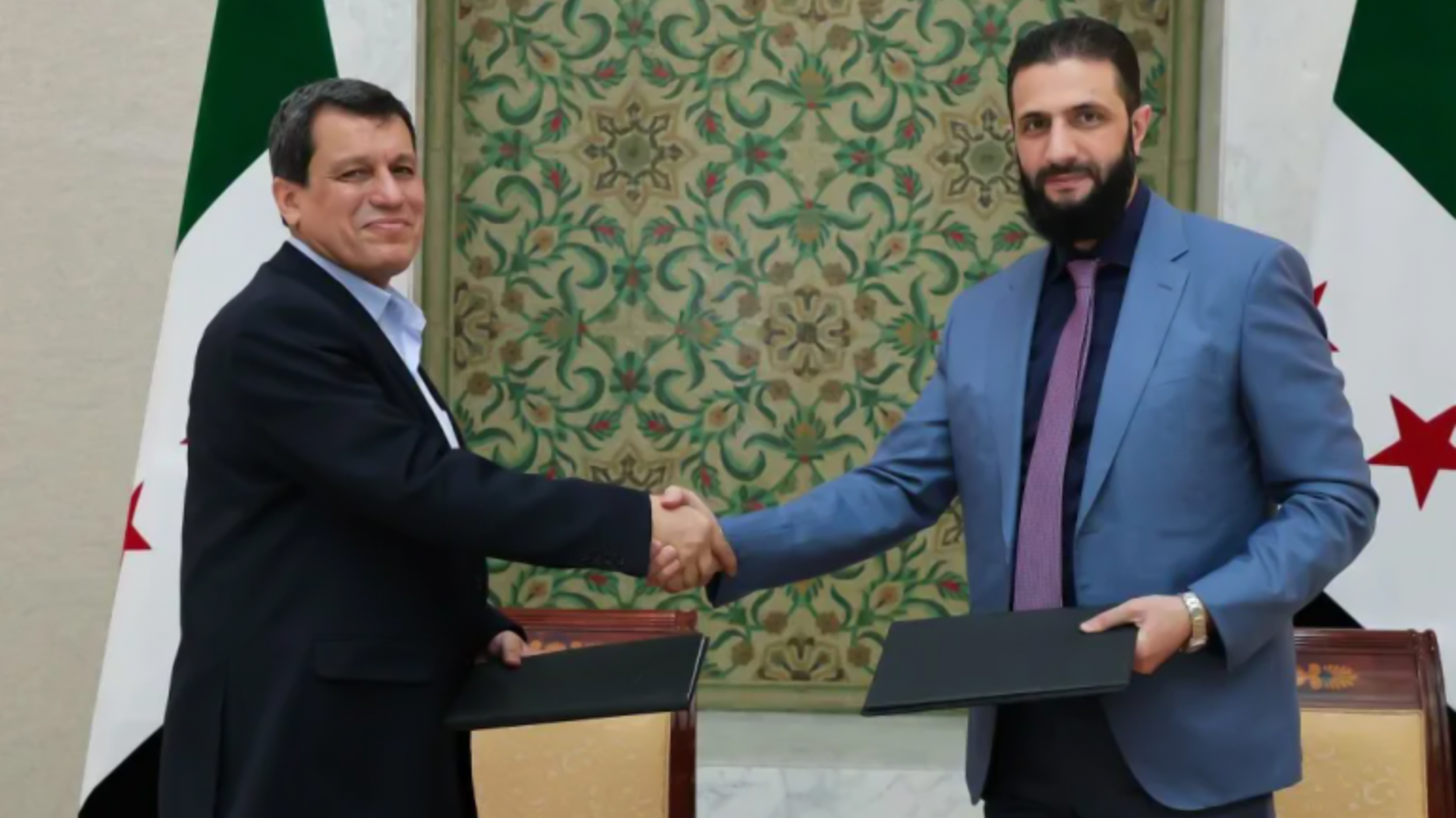

On 10 March 2025, Syrian President Ahmed al-Sharaa and the head of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), Mazloum Abdi, signed a historic agreement providing for the integration of the SDF into the Syrian army and the transfer of control of all civilian and military institutions in the northeast to the Syrian administration. Affirming that Kurds constitute an integral component of the Syrian people, the agreement guarantees the rights of all Syrians to representation and political participation and rejects partition of the country.

While talks between the new Syrian leadership and the SDF have been underway for three months, the two sides remained at loggerheads. The key sticking points were the SDF’s demands for a federal or decentralised state, a share of the oil and gas revenues in areas under its control, and the integration of its forces into the army as a single bloc, all of which Damascus rejected.

The sudden about-face was occasioned by three developments. First, in late February, Abdullah Ocalan, the leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in Turkey, called on the party to lay down its arms, dissolve itself, and join the democratic political fray in Turkey. While the outcome of the appeal remains uncertain, the SDF leadership, with its close ties to the PKK, is undoubtedly taking into account the rapidly evolving dynamics of the Kurdish question in Turkey.

Second, there are doubts about the Trump administration’s financial and military commitment to the SDF. Senior US officers reportedly met recently with SDF leaders to inform them of the imminent withdrawal of US troops from the area, urging them to reach an agreement with Damascus.

Third, the new Syrian administration’s successful quelling of the armed rebellion that erupted on the coast in early March, and the demonstrations of widespread Syrian support for their fledgling state, sent a strong message to all parties, including the SDF, that the state and the Syrian majority are prepared to defend the country and its unity. This message appears to have prompted divisive forces in eastern and southern Syria to reconsider their positions.

While the agreement offers considerable cause for optimism, its terms are formulated broadly, omitting details of how exactly the integration of SDF forces will proceed and in what manner the SDF will cede control of territory and oil and gas fields under its administration. The agreement leaves implementation to executive committees, which have until year’s end to execute its provisions, but the generality of its terms leaves ample room for conflicting interpretations, while the long lead time allows for the possibility of backtracking by the SDF.

The greatest fear is that the SDF’s decision-making process is not necessarily in the hands of leaders like Abdi, but rather rests with the PKK leadership in the Qandil Mountains, which may be disinclined to surrender its sole successful attempt at establishing a semi-independent governing administration in a Kurdish area. The SDF, too, may find it difficult to abandon the international ties it has forged with the United States, Europe and Russia since 2015 in favour of Syrian national integration.

Despite these concerns, the agreement represents a major achievement for al-Sharaa’s administration that will enhance its legitimacy and advance its goal of lifting the international sanctions imposed on the former regime. It could also have a far-reaching impact on the entire Kurdish question in the Levant. Even if the SDF leadership signed the agreement as a tactical manoeuvre, in anticipation of a later opportunity to further its long-standing objectives, the agreement gives Damascus valuable time to work on building new state security and defence institutions capable of preserving the country’s unity and sovereignty.

The day after the agreement was signed, it was announced that understandings had been reached between the Ministry of Interior and representatives in Suwayda to fully integrate the governorate into the institutions of the new government. The same day, the committee drafting the interim constitutional declaration announced it had completed its work. These developments would not have been possible—or would have been far less likely—without the defeat of the rebellion on the coast and the conclusion of the agreement with the SDF.

Beyond all this, the negotiating process between Damascus and the SDF could bring momentum to the peaceful, democratic shift on the Kurdish issue in Turkey, help ease the tensions between Iraqi Kurdistan and Baghdad, and dramatically change the trajectory of the Kurdish national movement as a whole. The post-World War I order in the Levant was a great disaster for Kurds, Arabs and Turks alike. Perhaps Kurdish, Arab and Turkish nationalists can now realise that salvation lies in working together to move beyond this order.

*This is a summary of a policy brief originally written in Arabic available here.