As soon as protests had begun in regular intervals in Khartoum and a number of different regions, analysts as well as demonstrators began recalling the path of the Arab spring revolutions to associate the nascent Sudanese protests to the Arab revolutions that led to the change, in multiple scenarios, of regimes in a number of countries over the past eighteen months.

How, then, can the Sudanese protests be read? What is their logic, dynamic of interaction and magnitude? To what extent do they affect the structure and cohesion of the ruling regime and pose a serious threat to its existence in power? What developments may the political landscape see in the near future?

Secession Blows the Winds of Change

Only a few months after the division ofSudaninto two states, the consequences arose politically, militarily and economically, forcing the Sudanese government, under the pressure of rather serious implications, to recognise the division of the country and the loss of unity with the loss of peace and renewed war. Furthermore, a more serious situation has emerged: Sudan on the brink of economic collapse because of its loss of the oil revenues that constituted the backbone of its financial resources for the past ten years.

In this difficult situation, the Sudanese government suddenly announced that the country is on the verge of economic breakdown if tough measures are not taken to rectify the deteriorating financial situation, a process that comes entirely in response to the IMF's suggestion of the removal of subsidies on fuel, national currency devaluation and the increase of tax and customs fees. Although government officials admit that these are stringent measures with severe impact on most citizens, they are the only way out of the crisis. Minister of Finance Ali Mahmoud called the move "an action by a bankrupt state," and in a speech, President Omar al-Bashir stated, "We are fully aware of the burden these economic measures will have on citizens in general but especially the poor. We would have avoided them if we were able to."

What came as a surprise is not the economic downturn, which the Sudanese have been facing over the past months, but the end the state of denial of the negative effects that separation has on the north. A common official justification maintained that the elimination of the burden of the south is an opportunity for the rebirth of a new Sudan that is free from the afflictions of unity.

In fact, the recent government measures have aggravated the political, military and economic tension that the country has been facing since secession with the outbreak of the new three wars in South Kordofan, the Blue Nile between government forces and Sudan People's Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) rebels, and later in Heglig, an oil rich region, between the armies of the two Sudans. There is a fourth battlefront in Darfur between government forces and factions of the armed movements in the region refusing to join theDohaagreement.

In a country that is already suffering from a financial crisis but spends more than two-thirds of its public budget on security and the military, these four-front wars have come to deepen the state of economic decline because of the government's need to increase military expenditure as well as the Heglig war that is costing the government about half of its oil production due to the widespread destruction of infrastructure carried out by the SPLA.

From Discontent to Protest

A wave of protests started on 17 June 2012 as the initiative of students from the University of Khartoum, a university with an imposing historical legacy that shaped the modern political history of the country, especially its role in the 1964 Revolution (the first popular revolution of its kind in Sudan and the region as a whole, and that ended the first military rule in the country.)

Tough economic measures are not the only factor that have prompted the protests though they have direct impact on increasing public discontent with government policies that affected all social segments thus causing the uproar of student and youth movements beyond the walls of the university and in many neighbourhoods in Khartoum and other cities in the country.

Despite the fact that the historical legacy of the Sudanese revolution transcends the era of the Arab spring with two revolutions in 1964 and 1985 that had toppled two military regimes, indicating the effectiveness of popular will and the accumulation of revolutionary experience and dynamism, it is clear that the protests are inspired by the spirit of the Arab spring that gives various divisions of the country's youth incentive.

It must be noted that attempts to mobilise protests took place earlier this year but authorities were quick to undermine them. However, this time the protest movement is decentralised and its area has expanded. It has also received greater attention from the media, giving it the impetus it needs to keep moving. The importance of the protest movement emanates from the fact that it managed to disrupt the government's nearly complete control of Sudan over the past two decades; and this control did not come overnight but was established through the ruling party's planning and management on the basis of the legacy of the country's Islamist movement that had great experience in inciting and mobilising mass demonstrations as well as the tactics and dynamics of protests. The regime uses this experience to tighten its grip on security and defuse the effectiveness of any potential popular protests.

In the preceding two revolutions of 1964 and 1985, student and trade unions that had strong political influence were the chief forces that were capable of planning the revolution and mobilising the public, while opposition forces followed to take part. When the current regime took over through a military coup in 1989, the first protective measure it took to safeguard itself was dismantling the "centres of the revolutionary action." It rushed to dissolve student and trade unions and replaced them with trade union organisations with controllable structures. It also sought to change the structure and nature of the solidarity and influence that characterised the work of trade unions over the decades, in which leftists, communists in particular, excelled.

This orderly dismantling of trade unions has denied the regime’s opponents the most important tools of mobilisation for opposition protest action. However, restrictions on peaceful labour opposition led to the spread of armed opposition backed from abroad in a manner that former military regimes had not known.

Therefore, it can be said that the current wave of protests, though still in its infancy, undoubtedly represents a qualitative shift in the confrontation between the regime and the opponents that seek to depose it. This is demonstrated by the hesitation the government showed when dealing with the protesters, uncertain whether to use persuasion and allow a degree of protest for the release of some public tension or use mass repression to prevent its spread – reflecting concern over potential interactions. Another factor that indicates the government’s recognition of the seriousness of the situation if protests escalate is that it was quick to block social networking websites used by the protesters as a medium for successful interactive networking among them whereby they exchange messages and organise events.

There are two major observations regarding the nature of the protest movement:

First: Although it erupted in the midst of tough austerity measures, its slogans and demands have quickly transcended the reality of the economic crisis to calls for the overthrow of the regime.

Second: Most of the movement's players do not raise partisan slogans, noting the active participation of women and partisan youth parties that rebelled against their opposition party leaders, accusing them of failing to confront the regime. These youth have overtaken the party frameworks and engage in protests without necessarily expressing the official position of their parties.

Discord within the Leadership

The protests erupted when the ruling party was not in the best of states. Last year, according to analysts, it lost a major bid for unity and peace, leading to the erosion of the government's political legitimacy and the decline in its abilities to manage the state. The economic crisis is just the tip of the iceberg that underlines the government's inability and failure to take early precautions against the repercussions of the country's division. This has raised widespread controversy among the ruling elite and activists who bear the responsibility for what happened.

What is ironic, however, is that the measures were objected to and protested against in the ruling party's institutions, especially by National Council deputies and the parliament (in which the ruling party controls more than 59 percent of the seats) before they were by the public itself. Last year, opposition was expressed when the state budget was being discussed and the Ministry of Finance proposed the elimination of fuel subsidies. Local media cited incidents of acute disagreement on the adoption of the measures within the ruling party in the past two months when MPs threatened to not pass them in parliament. However, they were subjected to intense pressure by government leaders who revealed the danger of the financial crisis pushing the government to the brink of bankruptcy under its failure to secure adequate external support.

Despite the apparent coherence in the ruling party's institutions, leaders' contradictory public statements and divergent positions reveal the depth of the increasing deficiency in the ruling class's structure, especially in light of the grumbling among ruling party activists about the continued dominance of one group of leaders of power in the party and the executive branch in the past two decades. There are growing calls for change and renewal of leadership, especially in the last few months in which a wave of internal protest ultimatums demanding reform in the ranks of the National Congress and its base in the Islamist movement emerged. Despite the fact that the ultimatums were not accepted, they revealed the magnitude of internal restlessness challenging the leaders of the ruling party. Thus, the current situation feeds on such protest movements, especially with the emergence of inertia and the lack of indications that the ruling elite will take on some degree of reform to meet the demands of the protesting grassroots.

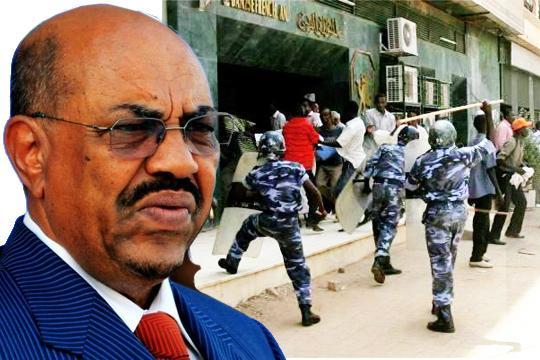

The main outcome of the protest movement, though underestimated, is that it pushed authorities to exercise the "security solution" against the protesters, thus increasing arrests and leading to the besieging of mosques as they have become the epicentre of the demonstrators' movement. This contributes to the regime's negative public image and subjects the regime to comparison with counterparts that were ousted by the Arab Spring – a significant element of moral pressure against the government.

Furthermore, the protest movement has brought more international pressure to the ruling party, which is already suffering due to the situation in Darfur and strained relations with South Sudan, with criticism from the United States, the European Union and the United

The Outcomes: Incomplete Remedies

The outcomes of the protests vary depending on how the authorities deal with the current developments and their willingness to benefit from the experiences of other Arab regimes that were overthrown by the revolutionary tide.

The government's main challenge is not only the protests, but its own inability to overcome the serious economic obstruction, congestion and deterioration resulting from the regime's mismanagement of the state. Analysts agree that the ruling party failed to anticipate the consequences of secession and the magnitude of its negative effects. It also failed to take advantage of the prosperity provided by oil revenues in anticipation of lean years. Instead, it preferred having a consumer economy to establishing a productive economy despite the country's abundance of resources and opportunities.

It is clear from the government’s actions since the start of the protests that its conduct is based on denial and justification rather than confronting pressing issues. It has resorted to undermining the protests, labelling them as a "Zionist-American" conspiracy, and relying on the security grip to repress the protesters.

However, the most striking example of confusion within government institutions is when President al-Bashir announced the austerity measures and considered them part of a comprehensive reform plan that includes the restructuring of government institutions to reduce the number of senior officials and cut down on government spending. While the government was quick to implement measures that affect the lives of citizens before even getting the parliament's approval, it was reluctant to implement those that concerned itself, such as government restructuring. This is due to internal conflict over maintaining existing interests that leaves the door open to different scenarios regarding what the conflict within the ruling party will lead to and whether the regime will crack, possibly prompting the army to jump in and rearrange the situation.

The protests themselves are expected to escalate not only because of the growing demands for change, but also because of the regime's confusion over the adoption of effective reforms. At a certain point, they may help reduce the public's enthusiasm for change as questions are raised about who will the alternative be.

Moreover, the harsh economic situation will worsen soon when the impact of the government's unprecedented increase of prices becomes clear and troubles most of the population, not to mention the lack of a political consensus and the effective plans to remedy the country's diminishing financial situation.

Among the factors that have so far kept the protests from going further is the absence of a central command for the movement in addition to the lack of a clear vision of a replacement for the regime. The main opposition forces signed a "democratic alternative" charter but due to differences among them failed to sign a constitutional declaration for the administration of the interim period.

The opposition's proposed alternative charter is undermined by the fact that it is based on the two transitional periods following the revolutions of 1964 and 1985 without taking into account the magnitude of the great transformations that have taken place in the country since then, such as the ignition of conflict between the centre and the periphery that led to the division of the country, and the outbreak of new conflicts between the centre and the forces of the new periphery in the "crescent of rebellion" that extends from Darfur to South Kordofan and the Blue Nile. Although, the opposition has called the Alliance of the Revolutionary Forces to sign the democratic alternative charter, the conflict is bound to persist due to the notion of "controlling Nilotic forces" that dominates the centre's manipulation of the country's future and excludes the participation of the peripheries' forces in creating the alternative.

The possibility of peaceful mass protests turning into armed violence is likely in the event the authorities' security grip is increasingly tightened. The intervention of armed opposition movements is also likely to influence the course of events under the pretext of protecting the "intifada."

It is apparent that the course of events will take two directions: the government will seek a method of agreement with South Sudan to benefit from oil revenues and acquire resources to decrease the wave of discontent while the protest movement continues spontaneously without the opposition's consensus given that the opposition is suffering from a major rift between its armed and unarmed factions. Thus, it cannot come to common terms regarding the overthrow of the regime unless it takes on a comprehensive security solution.