|

The resignation of Lebanese Prime Minister Najib Mikati has raised many questions about the timing, the declared and undeclared reasons, and particularly its effect on the implications of the Syrian crisis for Lebanon.

But the speed of the consensus on the assignment of Tammam Salam to form the next government unearthed the fact that there had been contacts behind the scenes that sought to create a new political climate to facilitate Lebanon’s adjustment to a "lengthy" Syrian crisis without dealing with an internal outbreak of conflict.

With the emergence of such a climate under the new government, holding the due legislative elections may become possible albeit with some delay. However, the problems and difficulties that the Mikati government suffered from will remain, especially those of the financial and economic situation and the acute polarisation of the Syrian crisis, its consequences and the envisioned aftermath of the Syrian regime.

Crisis Background

In the second half of January 2011, a political turning point took place when all the opposition ministers (who belonged to the 8 March Alliance) resigned from cabinet. Consequently, the government of Saad Hariri resigned, or rather was ousted, while Hariri was visiting U.S. President Barack Obama at the White House. In the consultations that followed for the assignment of a new head of government, it became clear that the parliamentary majority shifted with the withdrawal of Walid Jumblatt’s bloc from the 14 March Movement and Jumblatt's consent to assign Mikati, who was not affiliated with the movement but was considered part of it because he had won his parliamentary seat through an election deal.

That constituted an end to an internal crisis that began mid-2010 when it was clear that the Special Tribunal for Lebanon was getting ready to indict four members of Hezbollah for alleged involvement in the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri on 24 February 2005 and the deaths of 21 others. Secretary General of Hezbollah, Hassan Nasrallah, led a political campaign to drop the charges or sever all ties with the tribunal, which he accused of being "politicised" and seeking to undermine Hezbollah to serve the interests of Israel and the United States. The Syrian regime supported Nasrallah’s demands and pressured Saad Hariri to ignore the international tribunal and its accusations. A few months earlier, Hariri had fufilled Saudi Arabia’s request to mend fences with al-Assad. He dropped the accusations that the Syrian regime was behind the assassination of his father. But the reconciliation did not completely clear the name of Damascus, which, in theory, was acquitted as the perpetrator of the assassination. However, Syria later demonstrated its full solidarity with Hezbollah, which since the exit of Syrian troops from Lebanon (late April 2005) had become Damascus’s key ally, proxy and point of intersection in its alliance with Iran.

Bilateral mediation efforts of Saudi King Abdullah and the Syrian president (in late July 2010) temporarily eased the crisis and provided time for solutions. But the communication that took place between several capitals ending in Washington did not succeed in giving Hezbollah the answers and guarantees it sought. Among the many scenarios that were speculated at the time, a Shiite–Sunni rift was of the most dangerous. It then became apparent that the collapse of the consensual government headed by Hariri with the participation of the opposition was the least dangerous. That gave Mikati the opportunity to depict his acceptance of premiership as a "rescue mission" for the sake of the country and its stability. Initially, Mikati did not manage to form a consensual government, but the new majority offered him some concessions to make up for the resentment of constituencies that perceived his appointment as Damascus's decision and believed that he was only a cover for a rule controlled by Hezbollah, supported by its weapons. Hariri’s group believed that the ongoing pressures that led to the change in government and brought about the government of Mikati were actually the second phase of the 7 May 2008 invasion of Beirut by Hezbollah and its allies.

Interlacing with the Syrian Crisis

Before Mikati completed his initial consultations to form a government, indications of a Syrian revolution arose. Although he was technically dealing with one harmonious team hasty to reap the fruits of its political victory, he ran into many obstacles. The support of Damascus and Tehran for his government was not adequate; he had to ensure the acceptance and support of GCC States and Western countries, especially because of the bad financial and economic situation Lebanon was, and still is, suffering from. The government was formed in five months because the premier-designate could not satisfy his allies and Damascus was preoccupied with its own crisis and estimations of what it was to seek later from Lebanon. Mikati’s government finally saw the light in late June 2011. When it appeared before the House of Representatives to discuss the vote of confidence, the international tribunal issued its indictment list, naming four members of Hezbollah accused of killing (Rafic) Hariri. Even if the change of government had defused internal crisis, the indictment threatened the government with the potential outcome of the indictment. The real troubles, however, were coming with the gradual deterioration of the situation in Syria.

The government was at stake, not only because of the severe internal divisions, but also due to even severer polarisation over the Syrian crisis. The landscape soon took form: the 14 March Movement took a clear stance in support of the revolution, and aided the rebels’ demand to see the regime go. The 8 March Alliance advocated the regime's stay in power, with the Christian and Muslim populations divided between the two groups. Despite the persistence of this situation, the positions of the patriarchs of the Maronite, Orthodox and Catholic churches fostered much less enthusiasm towards the revolution in solidarity with Christian Syrians who saw that the regime was their best bet, fearing the revolution might bring to power militants who do not recognise pluralism and freedoms. The experience of Christians in Iraq was a disturbing reminder in this context. Thus, the Syrian crisis began to take a form of sectarian alignment in Lebanon, with alarming signs of a renewed civil war.

The Intensification of Sectarian Rift

It was not surprising that the crisis would take on a sectarian character for the following reasons:

1- Several internal events prior to the revolution had contributed to the intensification of this state of polarisation: the prevailing impression that the Syrian regime had assassinated Hariri, who was described by his supporters as the leader of the Sunnis; the 2005 uprising demanding Syrian withdrawal, a move which was not seen favourably by Hezbollah; the sudden alliance between Hezbollah and the movement of Michel Aoun, who has been known for his hostility towards the so-called “Sunni forces” since the 1989 Taif Agreement; the repercussions of the 2006 war and the ensuing power crisis. Then, there was the 2008 invasion of Beirut, which historically has been dominated by a Sunni population despite changes to its demographics as a result of the civil war (1975-1989).

2- The political changes in early 2011 that caused Mikati to become prime minister made Hariri believe that the Syrian and Iranian regimes alongside Hezbollah dominated such the premier’s post against the will of the Lebanese people. Meanwhile, these changes delivered a blow to Saudi Arabia's influence, which had always been one of the key elements of the political game in Lebanon in parallel with that of Syria. Thus, Hariri felt that he lost protection or regional cover.

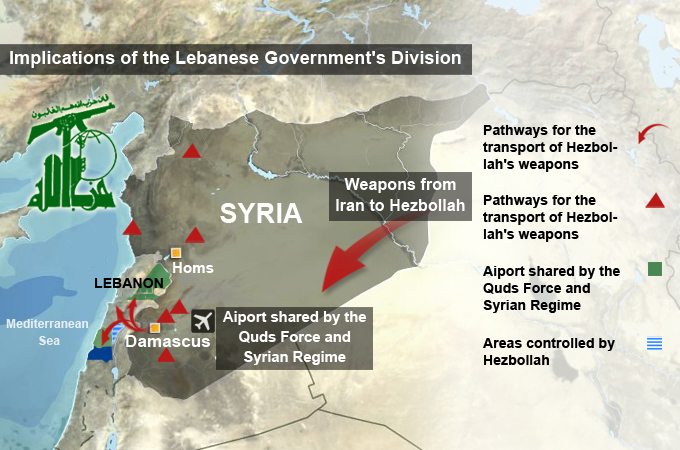

3- After the invasion of Beirut on 7 May 2008 and the Doha Agreement and its aftermath, Hezbollah was accused of using its weapons, which were originally meant for resistance to Israel, against fellow citizens at home. The demand to ration Hezbollah’s weapons is still on the agenda of the National Dialogue Committee, and Hezbollah continues to refuse to give up its arms. The 1989 Taif Agreement that ended the civil war stipulated the voluntary dismantlement and disarming of militias but excluded arms intended for resistance to the Israeli occupation. The day after the liberation of southern Lebanon in 2000, the fate of these arms was put forward, but the guardianship system the Syrians had imposed kept the weapons in the hands of Hezbollah and helped provide Israel with a justification for its repeated threats.

4- With the outbreak of the Syrian revolution, Damascus tried in more than one way to benefit from the government of Mikati, who was always considered one of its allies and was, alongside his brother, Taha, a business associate of Rami Makhlouf, Bashar al-Assad's cousin. Damascus sought Mikati’s cooperation in both security and intelligence to crack down on Syrian dissidents in Lebanon, who would then arrest hand them over to Syria. The Lebanese government was also expected to chase smugglers that provided rebels in Syria with arms. Financial cooperation was also expected, as Lebanon was requested to help Syria secure financial and commercial banking facilities to alleviate the impact of international sanctions. The government responded, thus enduring international criticism for its performance vis-à-vis the Syrian crisis. But the major countries showed flexibility in dealing with the Lebanese government as long as it was economically and politically able to ensure the stability of the country. It was also able to ensure Arab and international understanding of the “keeping distance” policy it followed in gatherings and conferences, opting to avoid voting for or against decisions related to the Syrian crisis.

5- The “keeping distance” policy did not affect the society. The positions of politicians on both sides have fuelled tension, but Nasrallah's speeches and Aoun’s remarks in favour of the Syrian regime have had the worst impact on the Hariri camp, as both were the dominant forces in the government. The violations of Syrian regime forces on the northern and north-eastern border, whether gunfire or artillery shelling targeting predominantly Sunni villages and towns, contributed to the escalation of sectarian tension. The outbreak of violence in the northern key town of Tripoli between residents of Bab al-Tabbaneh (a Sunni neighbourhood) and Jabal Mohsen (an Alawite neighbourhood) rang the alarm bells for the government, which tried – and is still trying – to contain the situation by deploying the Lebanese army. The army, however, has stands between the two neighbourhoods and is unable to enter. The north-eastern predominantly Sunni village of Arsal also suffers, despite the presence of the army, due to the siege imposed by Hezbollah as a result of Damascus's suspicions that it is a conduit of contraband weapons.

6- With the growing concerns that the situation may explode, it was possible in mid-June 2012 to bring together members of the National Dialogue Committee, which issued the Baabda Declaration in which various parties decided to distance Lebanon from regional conflicts, vowing not interfere in the Syrian conflict. But the information division of the Internal Security Forces revealed late August 2012 a plot to create sectarian strife through bombings targeting Sunni key figures and gatherings. Former minister Michel Samaha was arrested. In his confessions during the interrogation, he stated that the Syrian security official, Ali al-Mamluk, gave him the task of implementing the scheme and provided him with the necessary explosives. Two weeks before the incident, it was ambiguously announced for the first time that a Hezbollah officer was killed while he was on a "jihad mission" in the Syrian town of al-Qasseer. This was neither the first nor the last incident of its kind, but it triggered an overheated internal debate on the concept of "keeping a distance" and parties’ selective commitment to the Baabda Declaration. The 8 March Alliance defended both former minister Samaha and Hezbollah’s participation in the fighting in Syria, which only increased. Moreover, in late October 2012, a development exacerbated the sectarian tension, namely, the assassination of the head of the information division, Major General Wissam al-Hassan, in a bombing that targeted his motorcade. Fingers of accusation pointed to Syrian regime agencies and Hezbollah. Al-Hassan was a Sunni officer who worked on the development of the division and managed to garner support and cooperation from several Arab and Western countries. He succeeded in exposing the largest Israeli spy network in Lebanon and presented important data for the investigation of the assassination of Hariri. The uncovering of Samaha and al-Mamluk's scheme and later the assassination of al-Hassan constituted a turning point to President Michel Suleiman, who became bolder in his criticism of the Syrian violations. Prime Minister Mikati, however, realised he lost a lot morally and politically so he waited for the right time to resign and made the decision when the dispute over the election law heated up and 8 March forces refused to extend the services of Major General Ashraf Rifi, commander of the Internal Security Forces, who is considered a supporter of the 14 March Movement. According to sources, Mikati chose to withdraw hoping to be re-instated with a wider consensus. But circumstances had changed.

A “National Unity Government"

Contrary to the previous situation in which there were attempts to overthrow the government in January 2011, and before agreement on Mikati’s replacement, Tammam Salam, son of the late Prime Minister Saeb Salam, the scenarios expected were as follows:

1. A lengthy political crisis with the government serving as caretaker after its resignation.

2. A power vacuum exploited by Hezbollah to control the country and impose amendments to the Taif Agreement or come up with a new agreement.

3. Creating a “neutral” small-sized and short-lived government of technocrats, with the limited mission of overseeing the elections.

However, external contacts coupled and internal communications involving parties close to Hezbollah resulted in a fourth option that had been deemed unthinkable: a "government of national unity." It seems that the current conditions in the region and the continued Syrian conflict, confronted Iran with the need for flexibility and recognition of the status quo, especially as it realises that U.S.–Russian insight into Syria disallows for the crisis's spread to any neighbouring country.

In the past, Iran had shared management of Lebanese affairs with the Syrian regime. When the latter reconciled with Saudi Arabia in 2009 in what was known as the "S.S." (Saudi Arabia-Syria) agreement, it became possible for Saad Hariri to head a government of "consensus," and Iran remained a secret player behind Syria. However, with the overthrow of Hariri's government, the Saudi role was also knocked down. With the emergence of the Mikati government and as Damascus sank deeper into its own crisis, Iran started to run Lebanon through Hezbollah and Damascus’s allies. Then came the moment of choice for the Iranians to either monopolise control of Lebanon as the Syrian role erodes, or offer a compromise pending an end to the current stage and ease the burden of Hezbollah, which, in turn, insisted that a repetition of the Mikati experience is no longer possible. The party was willing to cooperate with any other person the (14 March) opposition named as premier as long as rivals take its conditions into account.

Bearing that in mind, some analysts described what is happening as a "return of Saudi Arabia" and its role in Lebanon. The premier-designate belongs to a family of politicians that is well-connected in Riyadh, which Salam visited before his designation. In fact, he met with Saad Hariri, who supports him, while the 14 March Movement announced his appointment although he is not one of its active members but a supporting outsider. It is interesting to see that Hezbollah and the Amal Movement supported his designation and that Hezbollah worked to convince its ally, Michel Aoun, to do so. It should not be inferred from this that Saudi Arabia and Iran are the custodians of Lebanon, with Iran substituting for Syria. Rather, it is recognition on the part of Iran of the need for a Saudi role to address Sunni forces’ resentment and end their boycott of the regime and the government. At the same time, Riyadh maintains its position, refusing contact with Tehran to address the problems in the region and preferring to discuss matters with local parties regardless of their religious affiliation.

Does this mean that the task of the new government and premier will be simplified and tension-free?

It could be if the government is formed quickly. Recent consensual governments took months to be formed. Another determining factor is the political concepts that will shape the new government’s agenda. After all, the main disputes, including Hezbollah’s weapons, participation in the fighting alongside Syrian regime forces, involvement in foreign issues amid demands to place it on the international list of terror groups and the international tribunal and the Hariri case, still exist. All this indicates that the consensus that could bring this government to power is likely to be fragile and vulnerable to turbulence. There are endeavors and agreements to revive the National Dialogue Committee to support the government and ease the pressure it faces, but this does not constitute a solid guarantee. Indeed, the current situation necessitates creative solutions to the crisis but the strategic options for Iran in Syria have not changed and, therefore, Tehran will not hesitate to use Hezbollah in a way that would undermine any consensus it sees as harmful to its interests.

___________________________________________

*Journalist and writer specialising in Lebanese affairs