| Abstract This report analyses Turkey’s 10 August 2014 presidential election results and examines their implications on several levels. As Turkey’s current prime minister and newly-elected president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan has ambitions to introduce constitutional reform and establish a “New Turkey” that will be associated with his name the same way Kemal Ataturk is associated with the Turkish Republic’s establishment. While questions remain about the Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) cohesion, Erdogan’s win has strengthened the party’s legitimacy, particularly in the face of internal divisions, reasonably strong opposition parties, and evidence the Kurds are likely to play an increasingly significant role in Turkish politics. Turkey now has a hybrid political system, one that is neither fully parliamentary nor entirely presidential. However, Turkey’s existing constitution does not allow for a semi-presidential system and this has created imbalance between state authorities and inconsistencies in their powers, something that cannot be solved without changing the constitution. The AKP is expected to announce who will take over from Erdogan as the new prime minister after its emergency party conference on 27 August. Erdogan’s inauguration as president is scheduled for the next day. If Erdogan’s plans for change are to succeed, the new prime minister will need to be close to him, enjoy his absolute trust and comply fully with his wishes. |

Introduction

The 10 August elections for Turkey’s twelfth president were also the country’s first direct presidential elections since the Turkish Republic’s establishment. The elections were won by the AKP’s candidate, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who obtained 51.8 per cent of the votes. Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu, the main opposition candidate backed by the Republican People’s Party (CHP) and Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), obtained 38.4 per cent of the votes, while the Kurdish Peace and Democracy Party’s (BDP) candidate Salahuddin Dimirtash received 9.8 per cent of the vote.

Erdogan is currently the leader of the AKP, Turkey’s prime minister and president elect. He has thus achieved the highest political position any Turkish citizen could achieve and now has several priorities, including addressing tensions with Fethullah Gulen supporters, continuing the Kurdish peace process and formulating a new constitution that reflects ongoing transformations in Turkey. This raises a number of questions about how the election results will affect political life in Turkey, what Erdogan’s immediate priorities will be, what shifts are likely in the coming period, and what form these will take in light of Erdogan’s intention to transform Turkey’s political system. This report is divided into five sections which will address these questions:

-

Analysis of the election results.

-

New president’s priorities for his first term in office.

-

Implications of election results for Turkey’s political parties.

-

Prospects for constitutional reform in Turkey.

-

Role of the new prime minister and new leader of the AKP.

Election results analysis

The election results were no surprise as Erdogan was expected to win (see Table 1). However, the margin he achieved was not as high as predicted in recent opinion polls (1) or by ministers who expected Erdogan to win between fifty-five to sixty per cent of the vote. (2) In fact, some analysts considered such exaggerated margins to be part of a deliberate polling strategy designed to encourage opposition candidates to withdraw and to dash the hopes of opposition-party supporters.(3)

Others considered these margins to simply reflect the state’s overconfidence given the absence of real competition. However, while the 51.8 per cent achieved by Erdogan secured his victory, it is not a sufficient mandate to enable him to change the country’s constitution. This will be discussed in more depth later in the paper.

|

| Source: Yeni Safak, http://secim.yenisafak.com.tr/cumhurbaskanligi/2014/ar |

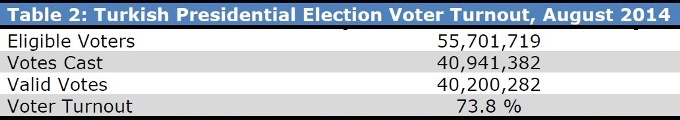

Voter turnout

Voter turnout was 73.8 per cent, which is relatively high when compared to similar elections in the west; however, the figure is lower than voter participation in past Turkish elections, particularly when one considers turnout for the 2011 parliamentary elections was at eighty-seven per cent and turnout for March 2014 local elections was at eighty-nine per cent. The lower turnout in the presidential election has been attributed mainly to a lack of motivation among opposition voters given that they knew the likely outcome and were unwilling to go to the polls during their summer holidays.(4)

This apathy cost the main opposition candidate dearly. In the previous parliamentary elections, the Erdogan-led AKP won about twenty million votes. In the presidential election, he obtained approximately the same number, but the opposition candidates lost approximately five million votes, four million of which were lost by the Republican People’s Party (CHP). (5)

|

| Source: Yeni Safak, http://secim.yenisafak.com.tr/cumhurbaskanligi/2014/ar |

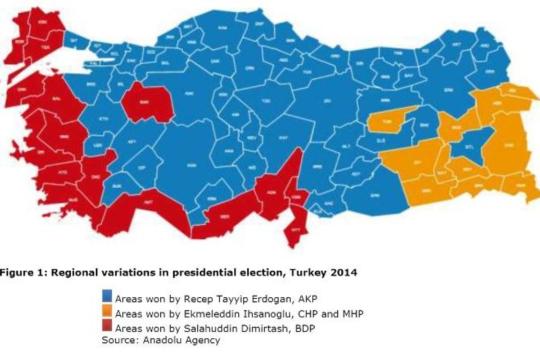

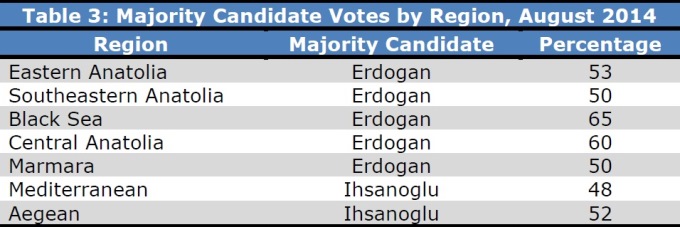

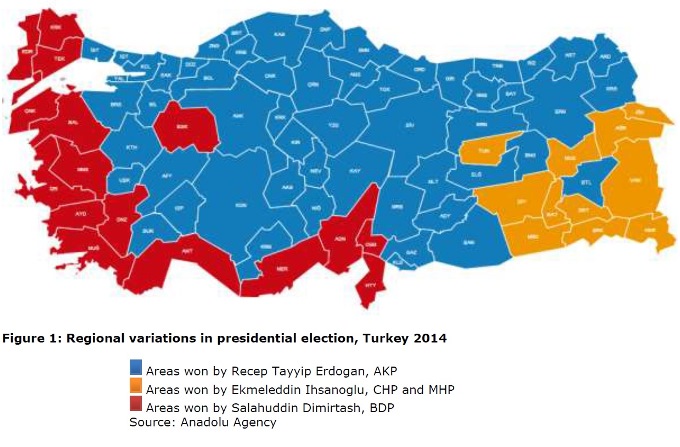

Regional distribution of votes

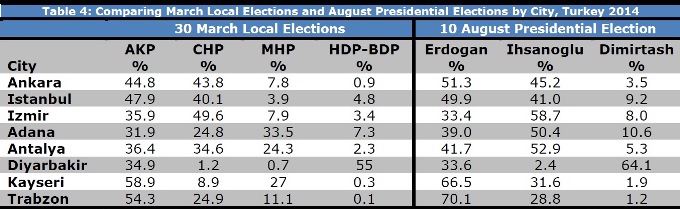

Generally, the results reflect few changes in relation to regional party allegiances. Majority candidate wins by region are shown in Table 3. As has occurred in the past, the majority of people in coastal areas voted in favour of the opposition candidate, Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu, and inland voters opted for Erdogan (see Figure 1). Some cities in the southeast voted in favour of the Kurdish candidate, Salahuddin Dimirtash.

|

| Source: Yeni Safak, http://secim.yenisafak.com.tr/cumhurbaskanligi/2014/ar |

|

| Source: Anadolu Agency |

Voting trends

It was striking that a number of the votes cast for the opposition parties – the Republican People’s Party and Nationalist Movement Party (CHP and MHP, respectively) – went to candidates other than Ihsanoglu, who was nominated jointly by the two parties. According to preliminary estimates, 750,000 to one million Republican Party supporters voted for a candidate other than Ihsanoglu. It is believed that many of these votes went to Salahuddin Dimirtash.

Similarly, it is estimated that around 1.7 million voters who previously voted for the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) voted for the AKP’s candidate, Erdogan. (6) This means that neither party was fully committed to supporting the joint candidate or were unable to convince their supporters to vote for him.

Opposition voters’ lack of support for Ihsanoglu is a clear indication of the internal crises these parties are experiencing. This is likely to have repercussions for the future structure and orientation of these parties. In contrast, the Kurdish Peace and Democracy Party (BDP) succeeded in doubling the votes it obtained in the previous election, far surpassing the four to six per cent threshold that Kurdish voter participation has been unable to overcome in previous elections. There is no doubt that this will have significant implications for the future of Turkish politics.

|

| Source: Daloglu 2014 |

New president’s priorities during first term in office

Erdogan’s speech from the balcony of his party’s headquarters in Ankara after the votes had been counted gives some indications about his orientations and the priorities of his domestic policies. These key issues are outlined in this section.

Firstly, conflict with Fethullah Gulen is likely to continue. Although Erdogan’s speech was filled with positive language and he promised to represent all Turks who voted in his favour as well as those who did not, he sent a clear message to the Gulen group when he said that he would firmly face entities that threaten national security. He called on supporters of what he called the “parallel state” and all righteous people to distance themselves from Fethullah Gulen and to avoid following him. In this context, it is likely that Erdogan will focus on prosecuting supporters of the group and on trying to locate their leader (or demanding that Interpol do so) so that he can be put on trial.

Secondly, Erdogan is likely to pursue social reconciliation with the Kurds, continuing the peace process he launched during his previous term. The debate will now begin to focus on Kurdish demands for some level of autonomous rule in parts of southeastern Turkey, something that many Turks are afraid of for the future and integrity of the country. The negotiations process is likely to be both delicate and complex.

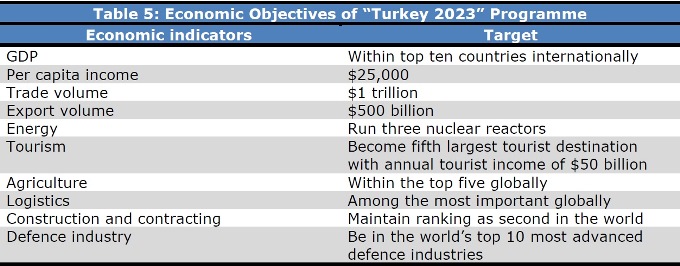

Thirdly, an attempt will be made to draft a new constitution better reflecting changes that have taken place in Turkey over the last decade and to satisfy Erdogan’s ambition to modify the political system (including clarifying presidential powers). This will also boost the AKP’s efforts to achieve their “Turkey 2023” programme as initiated by Erdogan in recent years. See Table 5 for a list of the programme’s objectives.

Fourthly, the “New Turkey” project will be implemented from the day of Erdogan’s inauguration as president on 28 August. This project is based upon attempting to achieve integrated political, economic, and social transformation that will raise Turkey’s status at the regional and international levels to that of a major player, laying the foundations for a second republic. As noted earlier, Erdogan would like this project to be associated with his name just as the name Ataturk is associated with the establishment of the modern Turkish State.

|

| Source: Bakeer 2013 (7) |

Implications of election results for Turkish politics

Ruling party

On the one hand, this election’s results will strengthen the AKP’s legitimacy as the ruling party and provide new incentive for the party to win by a wider margin in the July 2015 parliamentary elections. On the other hand, however, the ruling party faces a challenge because Erdogan’s rise to the presidency means that he will leave the party leadership (theoretically and legally at least), and the party has been extremely closely associated with Erdogan in recent years. This might be the impetus for these two occurrences:

-

Contrary visions between various factions within the party that might attempt to shift the party’s policies in new directions on certain issues.

-

Undermining the party’s internal cohesion. History has shown that shifting party leaders into the Turkish presidency has not been good for parties, such as Turgut Ozal in 1989 and Suleyman Demirel in 1993.

Another impact of these elections for the AKP is that around seventy-one of its members will have to leave office. Article 132 of the party’s internal regulations states that members who have been elected more than three consecutive terms shall not be allowed to stay in their positions. (8) This could affect the party if no unifying, strong party leader emerges.

Major opposition parties

After failing to win elections for over a decade, the opposition parties should use the August election results to review their aims and objectives for the future. A state of despair pervades the popular opposition forces, and calls have been made to hold the leaders of both opposition parties accountable for nominating Ihsanoglu as a candidate and for his poor performance in the elections. The leader of the CHP is likely to face fierce opposition and he may well be forced to resign at the party’s upcoming general conference.

It is obvious that new splits and polarisations are forming inside the opposition parties, and these might spread given the behaviour of opposition voters in these elections. (9) No doubt Erdogan and his party would like to see Turkey’s opposition parties remain as they are. However, a shift in the CHP’s general orientation seems likely, along with splits arising out of tensions around the choice of Ihsanoglu as the party’s presidential candidate. Factions are emerging within the party, including hardliners, as well as a more moderate current that hopes to alter the party’s position, aligning it more with the population’s general sentiment.

Similarly, it is possible that support for the MHP will erode over time on the grounds that part of its popular base, the “Islamist Nationalists”, particularly the young, may defect to the AKP. Indeed, this might explain why a number of the party’s votes went to Erdogan in the latest elections.

Kurdish parties

The elections revealed that Kurds have an increasing role to play in Turkish political life. For the first time, a Kurd was nominated as a presidential candidate, a fact that has enhanced the political legitimacy the group has earned as a result of the peace process launched by the AKP years ago. Although Salahuddin Dimirtash lost the election, the percentage he gained is expected to provide him and the BDP with a strong motivation to contest the next parliamentary elections, and to aim to win ten per cent or more of the vote. In addition, strong Kurdish leaders are emerging and they are capable of winning more concessions in ongoing negotiations with the government. This is strengthening the Kurds’ position as they demand more independent administration in the areas where they live.

Prospects for political reform

The current Turkish constitution was passed in 1982 after a military coup was staged by General Kenan Evren in 1980, who then appointed himself president and accorded his office wide executive, legislative and judicial powers to ensure that he could maintain a strong grip on the political system.

Although Article 8 of Turkey’s 1982 constitution states that executive authority is practiced and implemented by the president and the council of ministers, paragraphs a, b and c of Article 104 give the president wide authority. Nevertheless, until the August 2014 elections, the political system in Turkey has remained parliamentary, with the people choosing their representatives and those representatives in turn choosing the president. Prime ministers present their governments to parliament for a vote of confidence. In recent years, the role of the president in the parliamentary system has become mainly symbolic, with a small number of incumbents using the full extent of their powers other than in extreme and exceptional circumstances, and, even then, at a minimum level.

In 2007, Erdogan pushed for the constitution to be amended and to provide for the election of the president by the people. This was accepted, and the president’s term of office was set at five years and renewable once. Erdogan’s objective was to transform the political system into a presidential system, but he faced many difficulties, and the issue has remained hanging.

After the August 2014 presidential election, and with Erdogan’s promise that he will not be satisfied with a symbolic role and plans to be an active president, Turkey’s political structure has become unclear. It is no longer a purely parliamentary system (because the president has wide powers and is elected directly by people), nor is it a completely presidential system (because there is still a prime minister and a council of ministers who rely on parliament’s vote of confidence). In practical terms, the political system has become semi-presidential, although this is not explicit in the constitution.

This combination between a parliamentary system and a popularly-elected president with wide powers creates an anomaly that prevents the system from operating properly. It creates a state of imbalance between the authorities and inconsistencies in their powers. These problems can be addressed either legally or practically.

Legally, the problem can be overcome in either of two ways:

-

Obtaining a two-thirds majority vote in parliament (the Turkish parliament has 550 seats, so 367 votes would be required for this). The AKP only has 313 seats, and no other party is willing to join them in an alliance on this issue. The AKP therefore has to try to secure the necessary additional seats in the 2015 parliamentary elections. It is possible that they will hold elections at the end of 2014 to take advantage of the momentum built up by the presidential election, and try to extend their popular support base, but achieving the required majority will be difficult.

-

Offering a new constitution to the Turkish people and holding a referendum. However, reaching consensus on a new constitution that provides for a presidential or semi-presidential system won’t be easy. The opposition parties are clearly against this, and all the major parties are evenly represented on the constitution drafting committee. The AKP is not entitled to impose what it wants on others.

Practically, it is possible to overcome this problem and circumvent the obstacles if the president and the prime minister agree, or if the prime minister at least does not oppose the president. In this case, the constitutional provisions can remain as they are, but practically the president will be the de facto leader who dictates what he wants from the government and its prime minister. Erdogan in particular will have the necessary influence to achieve this because he is a founding member of the AKP and one of the reasons for its success. He also has a hold over many of AKP members because they owe him a great deal. However, this option would be unstable and unlikely to last because it will undermine the separation of powers and erode both state institutions and the law.

New prime minister’s role and AKP’s new leader

Erdogan has until 28 August 2014 to resign from his post as prime minister. This is the day on which he is expected to be sworn in as president, thus ending the mandate of the current president, Abdullah Gul. Turkish law decrees that the president cannot be partisan, which means that Erdogan will have to resign as both leader and member of the AKP. These changes raise many questions about who will step into the important roles of prime minister and AKP leader, and about the nature of their relationship with the future President Erdogan.

Prime minister’s role

Traditionally in Turkey, the leader of the ruling party becomes prime minister. This formula could be adopted again in the present circumstances. A new party leader will be named as Erdogan’s successor at the AKP’s emergency conference scheduled for 27 August and the new leader will then be commissioned by the president to form a government. Alternatively, because of the special circumstances, a new party leader could be named to succeed Erdogan and the president of the Republic (Erdogan) could then commission someone else to form a government.

Either way, the next prime minister of Turkey is likely to have to occupy the office on a temporary basis and focus mainly on preventing confusion from disrupting the political system until the next parliamentary elections are held. The new prime minister will have to co-operate closely with Erdogan, enjoying his absolute trust, complying fully with what the president demands, never questioning what he says or challenging what he proposes. In this way, Erdogan will ensure that no conflict arises between his powers and those of the prime minister and work of the government will continue in a reasonably harmonious fashion.

Several AKP members who fulfil these requirements have recently surfaced. They include the minister of foreign affairs, Ahmet Davutoglu; former transport minister, Ben Ali Yildirim; AKP vice president, Mehmet Ali Sahin; and deputy minister for economic affairs, Ali Babacan. From time to time, other names have been proposed such as Numan Kurtulmus, a conservative, or Bulent Arinc, who is unlikely to be as malleable as the others.

AKP leadership

Because the law states that the president must have no party affiliation, Erdogan is afraid to lose power and the ability to influence the party he helped establish and whose popularity is associated with him personally. Erdogan will need the party to remain loyal to him so that he does not become isolated in the presidency. He is therefore working hard to organise his affairs within the AKP to ensure that it will serve his objectives when a new party leader is announced on 27 August. However, Abdullah Gul’s announcement that he plans to return to the party he co-founded raises questions about how, when and in what position he will return. It is very likely that Gul would like to return as party leader as this would help the cohesion of the party, give it a new impetus and help it to better prepare for the upcoming parliamentary elections. This may mean Gul assumes the position of prime minister. But, this might create some challenges for Erdogan unless he can reach a prior agreement with Gul on the role of each in the next stage. Gul is unlikely to accept Erdogan’s commands if he becomes AKP leader, nor would he be willing to be a symbolic prime minister in if he assumes this office after the next parliamentary elections.

_____________________________________________________

Ali Hussein Bakeer is a researcher specialising in international relations and strategic affairs.

Endnotes

1. Ali Hussein Bakeer, “Way to the Turkish Presidential Elections”, AlJazeera Centre for Studies, 16 July 2014, http://studies.aljazeera.net/reports/2014/07/201471610848455343.htm.

2. Information obtained by author from sources who declined to be named.

3. Ali Aslan Kilic, “AK Party Finds Way Out After Being Cornered”, Today's Zaman, 11 August 2014, p. 5.

Pinar Trembley, “Why Did Turkish Expats Ignore Erdogan’s Call to Vote?”, Al-Monitor, 7 August 2014, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2014/08/tremblay-elections-expat-turks-votes-disappoints-erdogan.html#.

4. Murat Yetkin, “Erdo?an’s Time in Turkey”, Hurriyet Daily News,11 August 2014, http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/erdogans-time-in-turkey.aspx?PageID=238&NID=70239&NewsCatID=409 ; and Cafer Solgun, “No Surprises, Only Lessons”, Today’s Zaman, 11 August 2014, http://www.todayszaman.com/columnist/cafer-solgun/no-surprises-only-lessons_355294.html

5. Aydin Albayrak, “Lack of support led to failure of joint candidate”, Today’s Zaman, 11 August 2014, https://www.todayszaman.com/national_lack-of-support-led-to-failure-of-joint-candidate_355338.html.

6. Ali Bakeer, “Future of Turkey’s Role in Gulf Region During the Coming Decade to 2023”,conference paper presented during Challenges and Transformations Facing Kuwait and The Gulf During the Current Decade, Kuwait University, 25 – 26 November 2013.

7. Tulin Daloglu, “Turkish Opposition Remains in Denial of its Failed Strategies”, Al-Monitor, 11 August 2014, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2014/08/daloglu-presidential-elections-erdogan-opposition-denial.html.

8. Article 132 can be viewed at www.akparti.org.tr/arabic/akparti/parti-tuzugu.

9. Ironically, Salahuddin Dimirtash got about fifty-two per cent of the votes in Tunceli, the province that is home to the leader of the Republican People’s Party (CHP) which supported Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu.