Abstract

Unease about America’s democracy pre-dates President Trump. During the last three or four decades, the constitutional and cultural setting has changed radically. Sophisticatedly organized corporate interests have usurped power from the constitutional arena and left Congress, in particular, diminished. Constitutional dysfunction is wrapped into a culture of division and polarization in both society and politics. The Office of President holds vast powers and the inclinations of the person who holds the Office is eminently relevant in any analysis of American politics. The reason warnings against the Trump presidency are valid is not that Mr. Trump is an unpalatable human being, but that a person of non-democratic inclination has won the powers of the presidency in a setting in which both the constitutional system and the political culture are weakened. No cure of these underlying weaknesses is in sight. In at most seven years, President Trump will have gone. The question is how much lasting damage will have been done by then.

The Warning

It is a sign of the fragile state of democracy in America that when the outgoing president used his final State of the Union Address to warn of democracy “grinding to a halt,” hardly anyone was able to hear what he said. This was on the 12th of January 2016. President Barack Obama called on his fellow Americans that “we fix our politics” and said this was “the most important thing I want to say tonight.” He was delivering one of the most monumental presidential speeches ever, radical in substance and rich in rhetoric. But it passed by, not so much ignored as just not heard.

The last time a president warned the country in similar stark terms was when Eisenhower, in his farewell speech in 1961, raised the specter of the military-industrial complex whose “economic, political, even spiritual” influence was “felt in every city, every statehouse, every office of the federal government.” Had America heeded its wise leader then, it might have saved itself from the emergence now of an even more powerful politico-corporate complex. Had Americans heeded another wise leader two years ago, it might have been able to start pulling itself out of the quagmire it has instead fallen deeper into.

The American public opinion has had similar concerns. One month before the 2016 presidential elections, 40 percent of registered voters said they had lost faith in American democracy. Similarly, the level confidence in US government institutions has shrunk from the majority of 73 percent in 1958 to mere19 percent in 2015.(1) The Economist Intelligence Unit recently downgraded the United States to a 'flawed democracy,' placing it 21st in the international rankings. It established the grading criteria on five categories: electoral process and pluralism, functioning of government, political participation, political culture, and civil liberties. Robert Denton, co-author of "Social Fragmentation and the Decline of American Democracy: The End of the Social Contract,” argues that "When there’s a lack of confidence and trust then you lose those values that hold society together and ... we lose sight of the common good… That erodes the fabric of democracy."(2)

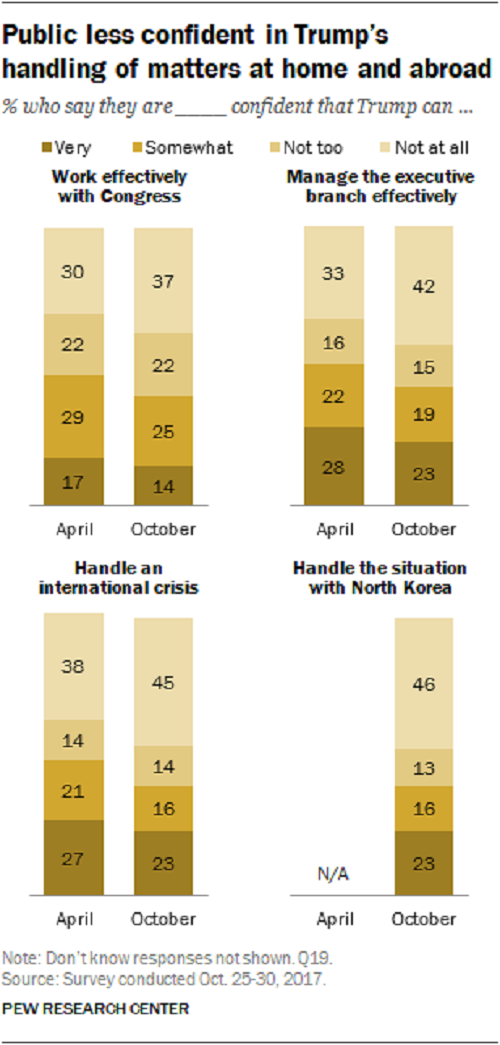

|

| American Public less confident in Trump’s handling of matters at home and abroad (November 2, 2017, Pew Research Center) |

The Backdrop

When Alexis de Tocqueville travelled through America for nine months in 1831, his aim was to explore how a system of political equality worked (and to let the French know that democracy was all but dangerous). He was, as he no doubt expected, impressed with what he saw. Under the American Constitution of representative democracy and in the absence of aristocracy, citizens were equal and saw each other as equals. There was a relationship of harmony between government and people that made for stability of governance from above and trust in governance from below.

Of course, the America through which Tocqueville travelled was not a society of equality. It was a slave economy. The Native American populations were being driven out of their ancestral lands. Women were excluded from democratic participation. Tocqueville knew and saw all of this, but he also saw an absence of hierarchy among those who were included. That formed the core of what he reported in two volumes on la démocratie en Amérique, published in 1835 and 1840.

Two observations stand out in his rich and nuanced analysis. One is that if democracy worked well for the Americans, that was not simply because it was laid out under an orderly constitution but as much because that constitution rested on a democratic culture. This was a culture of associations, not least church and affiliated religious associations. Citizens were not loners, they had belonging and community. They were not on their own up against the might of the state but had the support of intermediate structures that cushioned what could otherwise have been confrontational state-society relations. The state was felt to be relatively benign and under control. There could be trust because the state did not have the dominating presence of being dangerous.

Another observation, much in evidence in his second and more critical volume, was that if democracy worked for the Americans, it was far from perfect. Not only was much of society excluded from belonging in the polity, there was an undercurrent of dysfunction within the polity itself. The balance in state-society relations was fine and delicate and subject to disintegrating, even into what he called le despotisme doux, soft despotism. There could be an erosion of freedom within a shell of democratic formality, which citizens might allow to fester out of greed and indifference, gradually and hardly perceptively.

There is a direct line from these observations by Tocqueville during the infancy of American democracy to the works of its most eminent recent theoretician, Robert A. Dahl. In a string of books and articles, Dahl was at one and the same time a firm defender of America’s democracy, including in the period when it was under disdain by analysts of Marxist inspiration, and a sharp critic of shortcomings and weaknesses in that same democracy. Towards the end of his life pulled together what he had learned in three brief and beautiful books, “On Democracy” (1998), “How Democratic is the American Constitution?” (2001), and “On Political Equality” (2006).

In “On Democracy”, he follows Tocqueville in the importance of political culture. No democracy can work well with the help of only a constitution, however carefully designed. It depends also on support from below, from beliefs, ways of thinking and habits of trust and confidence. “The prospects for stable democracy in a country are improved if its citizens and leaders strongly support democratic ideas, values and practices. The most reliable support comes when these beliefs are embedded in the country’s culture and transmitted, in large part, from one generation to the next. In other words, the country possesses a democratic political culture.”

He also follows Tocqueville in finding fault in the democracy he admires. In “How Democratic is the American Constitution?” he does not say, obviously, “not at all,” but he does say, “not very.” He is critical of a poorly representative Congress, in particular in the Senate. He is critical of the power that the Supreme Court has come to hold, which he describes as “an aberration.” He is critical of the convoluted way the president is elected, which on numerous occasions has enabled a candidate to win the presidency without a majority of the popular vote (which was to happen again for Donald Trump in 2016).

In “On Political Equality”, his final book, Dahl thinks that a failure to stand guard over democracy has hollowed out the reality of political equality. The main culprit is the easy access to political influence of economic inequality. “Because of a decline of the direct influence of citizens over crucial governmental decisions, and also in the influence of their elected representatives, political inequality might reach levels at which the American political system dropped well below the threshold for democracy for democracy broadly accepted at the opening of the twenty-first century.”

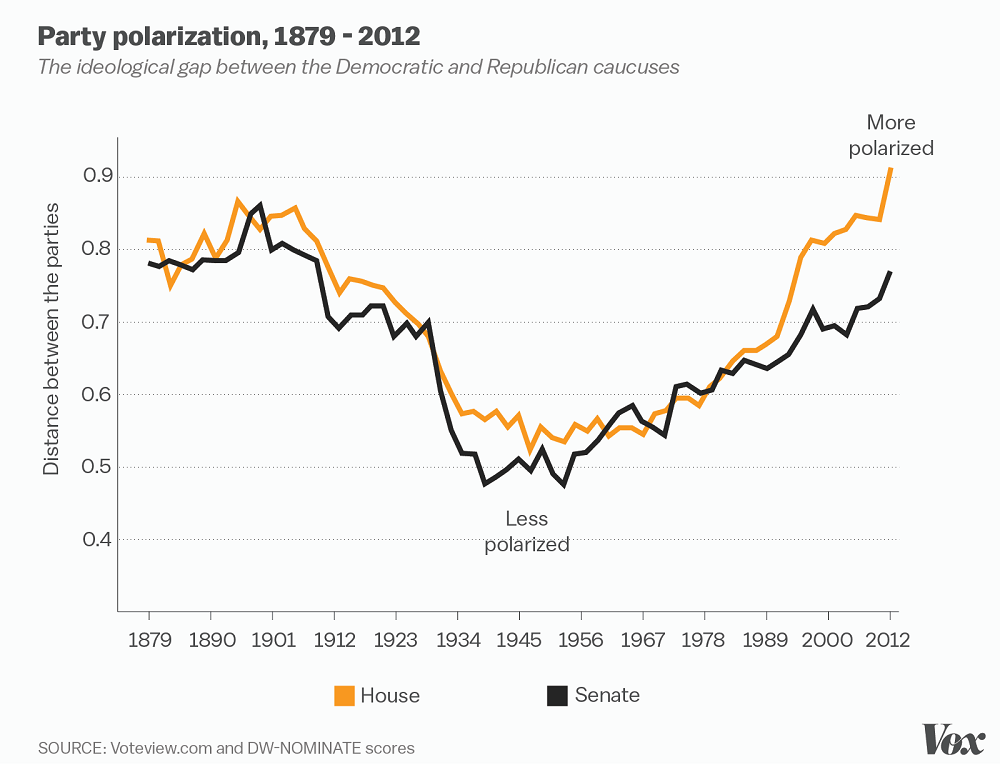

|

| Party Polarization and ideological divergence in the United States (Vox) |

The Predicament

Under the erratic presidency of Donald Trump, underlying anxieties about democracy in America have burst through the surface. The comments pages in serious newspapers run rafts of articles about democratic doom that a year ago would have been thought outlandish. A recent scholarly book, “How Democracies Die” (2018, by Daniel Ziblatt and Steven Levitsky), considers the possibility of democracy collapsing under the onslaught of a president of authoritarian persuasion.

However, unease about democracy pre-dates Mr. Trump. President Obama issued his warning at a time a Trump presidency was not seriously thought possible. For my own part, I published an op. ed. in the Washington Post under the title “Is American Democracy Headed to Extinction?” in March 2014. Most who are uneasy with the Trump presidency, see it rather as a symptom than a cause. If so, a symptom of what?

Mr. Obama, in his final State of the Union Address again, answered that question in an analysis that was exceptionally direct and perceptive. Washington is dysfunctional. The reason, he said, is that elected representatives are “trapped” by “imperatives” and in “rancor” which they dislike but cannot get out of.

The imperative is that of raising money, “dark money” he called it in his 2015 Address. That pulls everyone into the rancor of having to outshout each other.

When Washington is unable to act and turns into a shouting match, the next bastion to fall is trust. “A better politics doesn’t mean we have to agree on everything, but it does require basic bonds of trust between its citizens.”

The reason trust brakes down is that “those with money and power gain greater control over the decisions” that are made in Washington. “And then, as frustration grows, there will be voices urging us to fall back into our respective tribes.” And further: “Democracy breaks down when the average person feels their voice doesn’t matter; that the system is rigged in favor of the rich or the powerful or some special interest. Too many Americans feel that way right now.”

President Obama was here offering an analysis that echoes those of Tocqueville and Dahl. The Constitution requires a fine balance between the main constituent parts – the legislature, the executive and the judiciary – whereby they check each other but also together deliver trustworthy governance. That relationship is now out of balance, the result being gridlock instead of a fine-tuned combination of checks and collaboration. The victim of this imbalance is in particular Congress, the institution of “trapped” representatives.

Furthermore, constitutional dysfunction is embedded in a morass of confusion in the political culture, characterized by feelings of disempowerment, frustration, lack of trust, tribalism, anger, rancor. Gone are Tocqueville’s orderly state-society relations. In their place is a rigged system where special interests hold sway “up there” while “down here” ordinary folks count for nothing.

Economic influence over public policy is as old as democracy. But the way economic power is now exercised in the American system is radically new.(3) Monied interests have grasped that it is not enough to use economic power to influence the making of public policy in Washington. That’s to get into the act too late. Over the last two or three decades, those President Obama called “the rich and the powerful” have worked systematically to add ever more sophisticated organizational power to their already formidable economic power. Corporate resources have invested in a vast web of PACs, think-tanks, lobbying groups and media organizations. And while they have built up new structures of power, their old counterpart, Labor, which has traditionally relied on organizational power, has lost ground. The power of backstage influence has been both augmented and monopolized by the special interests of money and corporations.

In America’s now mega-expensive politics, what candidates and representatives are “trapped” into, is dependency on the money and power of the spiders in this web. Political candidacy has become forbiddingly expensive so that it has become impossible to run for national or state office, other than exceptionally, without economic backers. Those who get elected engage in political battle and decision-making as usual, but organized money controls who the deciders will be – those acceptable to the backers – and what they can decide – that which is acceptable to organized money. It looks like politics as usual, but power has been removed from the political arena, from Congress, and usurped into the new politico-corporate complex of monopolized backstage organization.

This constitutional dysfunction is wrapped into a political culture of polarization. From the 1970s, economic inequality has widened radically. While the rich have become richer, working and middle class families have seen little or no improvement in wages and living standards. The share of total income accruing to the richest one per cent of households increased from about 8 per cent to about 18 percent. A new wedge of social division has been driven into the population.

The inevitable result is mutual distrust, manifested in survey data. From 1994 to 2016, the proportion of Democrats and Republicans respectively whose view of the other party is “very unfavorable” increased from 16 and 17 percent to 55 and 58 percent. By 2016, 41 percent of Democrats and 45 percent of Republicans saw the opposite party as “a threat to the nation’s well-being.” In a shocking statistic, again in 2016, 60 percent of Democrats and 63 percent of Republicans “would be unhappy if their children married someone of the opposite party.” In 1960, there was no such sentiment at all. Since then, distrust has taken hold and widened relentlessly.

Social polarization follows through to political polarization is Congress and statehouses. Since the 1970s again, and reflected in statistics on party mean positions on political issues, the two main parties in Congress, and even more in statehouses, have drifted apart into mutually hostile tribes (to return to President Obama’s language), disinclined and unable to collaborate and compromise.(4)

What we see in these statistics is not only a political culture of polarization, but one that in a relatively short time has slid from reasonable cohesion to sharp and deep division.

|

| Stein Ringen’s book “What Democracy Is For: On Freedom and Moral Government “ |

The Trump Factor

The Office of President holds vast powers. The Constitution wisely constrains that power by checks-and-balances. No president can do whatever he wants, but his powers nevertheless enable him to exercise wide-reaching influence in governance and society. The character and inclinations of the person who holds the office is therefore eminently relevant in any analysis of American politics.

Donald Trump is an absolutely astonishing person to be President. He is a man who displays utter disregard of the truth and contempt of ethics, culture and civility. He has no hesitation in using the presidential office as a bully pulpit against opponents and critics from within political and civil society, and to do so with both pettiness and brutality – remember the assault on the actress Meryl Streep for taking him to task for having made fun of a disabled journalist for his disability. In How Democracies Die, the authors describe him as dangerous in that he combines four authoritarian characteristics: a weak commitment to democratic rules, denial of the legitimacy of opponents, tolerance of violence, and willingness to curb civil liberties and the free press.

Still, America has had many odd presidents and democracy has survived them all. Normally it should not matter; presidents come and go and the Constitution prevails. But these are not normal times. The constitutional system is weakened. The political culture is weakened.

Mr. Trump presents himself as a radical outsider on a mission to do battle with the Washington establishment, the press and the policies of his predecessor. In legislation, he has not achieved much. Congress has accommodated him on tax reform, denied him the overturn of “Obama-care,” and is holding him in check on immigration reform. But legislation has so far not been his primary arena of influence. He has won the battle of the agenda. Political discourse in America now is entirely on the President’s terms. Much of that discourse is critical, but even the criticism is on his terms. He has won the battle of the language. The discourse is mean and confrontational. His daily and rough attacks on the press have become normal, and the language of “false news” the accepted terminology. He has, says the columnist Roger Cohen (in the New York Times, 2 February 2018), achieved “a kind of numbness and exhaustion of outrage that allows him to proceed with the unthinkable.”

As in these examples:

- In the context of rising racial tensions in the nation, the President, in a speech to law enforcement officials on the 28th of July 2017, encouraged “rough” practices, asked of police officers, “Please don’t be too nice,” and added, of the law, that it is “stacked against” the police.

- On the 25th of August 2017, the President pardoned the former Arizona sheriff Joe Arpaio who had been charged with contempt of court for refusing to obey a court order to desist with unlawful police practices towards immigrants and Latinos in his district. The President lavished praise of Mr. Arpaio whose life and career “exemplify selfless public service” and who was “convicted for doing his job.”

- In his first State of the Union Address on the 30th of January 2018, the President announced the continuation of the detention facilities at Guantánamo Bay,” adding that he expected that “in many cases” captured terrorists would be sent to the camp. A President governing under a rule-by-law Constitution, speaking in the Congress of that Constitution, declares a prison facility operating outside of the rule-of-law to be a normal, indeed desirable, institution of the Republic.

Congress is charged under the Constitution to check the President. It is so doing in some matters of legislation. But when the President uses his powers to undermine core norms in the rule-of-law, that Congress, except for some lone voices, is silent. Indeed, when the President made his Guantánamo pronouncement, half of the representatives stood up to applaud. Congress, in a Republic founded on the rule-of-law, applauds the perversion of the rule-of-law! Numbness and exhaustion indeed.

The reason the warnings against the Trump presidency are valid is not that Mr. Trump is an unpalatable human being. They are valid for a particular combination of reasons that are coming together at this time:

- A man with undemocratic instincts and inclinations has captured the Presidency.

- He is displaying ruthlessness in the use of the powers of his office, against the grain of a democratic Constitution.

- This is in a political culture of divisiveness and distrust in which confidence in democracy and democratic values has been in decline.

- And against the backdrop of a Congress without authority. So far, Congress as an institution has rather given a brutish president free reins than risen to correct his excesses.

Is There a Cure?

It would be possible to break the monopoly power of the politico-corporate complex by regulating the political use of corporate money. Such regulation started more than a century ago under the Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt but has in recent years been almost totally disbanded by rulings of the Supreme Court. That Court has fallen under the spell of a bizarre doctrine that holds the putting of money to political causes to be a form of speech, and hence protected under the Constitution’s First Amendment. There is nothing to suggest a change of heart in the Court and therefore little prospect of re-regulation.

How a broken democratic culture could be mended is difficult to see. It was President Obama’s great vision to overcome the politics of rancor and to restore Washington to a lost habit of competitive collaboration. But in that he failed. A leadership that could fare better does not seem to be in the cards.

What needs to be understood about democracy in America is how radically the constitutional and cultural setting has changed during the last generation. Professor Mansbridge, whose statistics I have referred to above and who has looked more carefully into the politics of polarization than most, has concluded that the present predicament is “the new normal.” The best Americans can hope for, it would seem, is that President Trump, as previous presidents, will come and go, that not too much lasting damage will have been done, that the Constitution prevails, and that the next president is a man or woman of democratic instinct.

1- Pew Research Center, “Beyond Distrust: How Americans View Their Government”, November 23, 2015

http://www.people-press.org/2015/11/23/beyond-distrust-how-americans-view-their-government/

2- Gretel Kauffman, “US no longer a 'full democracy' in 2016 Democracy Index: Where do we go from here?”, The Christina Science Monitor, January 26, 2017

3- I here draw on J. Hacker and P. Pierson (2010) Winner-Take-All Politics (New York: Simon & Shuster 2010) and my own Nation of Devils (New Haven; Yale University Press 2013).

4- I am grateful to Professor Jane Mansbridge of Harvard’s Kennedy School for sharing these and related statistics with me.