Abstract

To most people, Brexit appears to be one member of an economic union abandoning the other 27 members and striking out on its own. This view of Brexit does not capture the dynamics of an unprecedented process because 1) the European Union is more than an economic arrangement; and 2) Great Britain is a member under conditions different from the other national governments. These special conditions lie at the heart of the Brexit process.

Brexit itself represents the unintended consequence of long-standing conflicts within the British Conservative Party. In 2016 motivated by internal tensions within the Conservative Party and confident of a decisive victory, then-British Prime Minister David Cameron scheduled a referendum on membership in the European Union. Voter rejection of the referendum forced the collapse of the Cameron government and its replacement by pro-Brexit cabinet led by Theresa May whose decision to call a snap election a year later left the Conservatives with a weak minority government. Simultaneously, the disruptive effect of the referendum transformed the Labour Party, shifting power to its EU-skeptic leader Jeremy Corbyn. Legal means exist that might allow a reversal of Brexit. Without a dramatic shift in public opinion no current or foreseeable government will take the steps necessary to reverse Brexit. On the European side the European Commission and almost all the national governments consider it definitive that Britain will leave the Union.

Brexit Basics

At a superficial level the origins of the European Union involved agreements narrowly focused on economic cooperation. The word cooperation is essential to understanding the early stage of the European integration movement, which sought to facilitate recovery after the Second World War by limiting market competition in key parts of heavy industry, for example the European Coal and Steel Community. The economic agreements derived from a deep political purpose, to end political conflict in Europe and replace it with a cooperative spirit among governments and peoples.

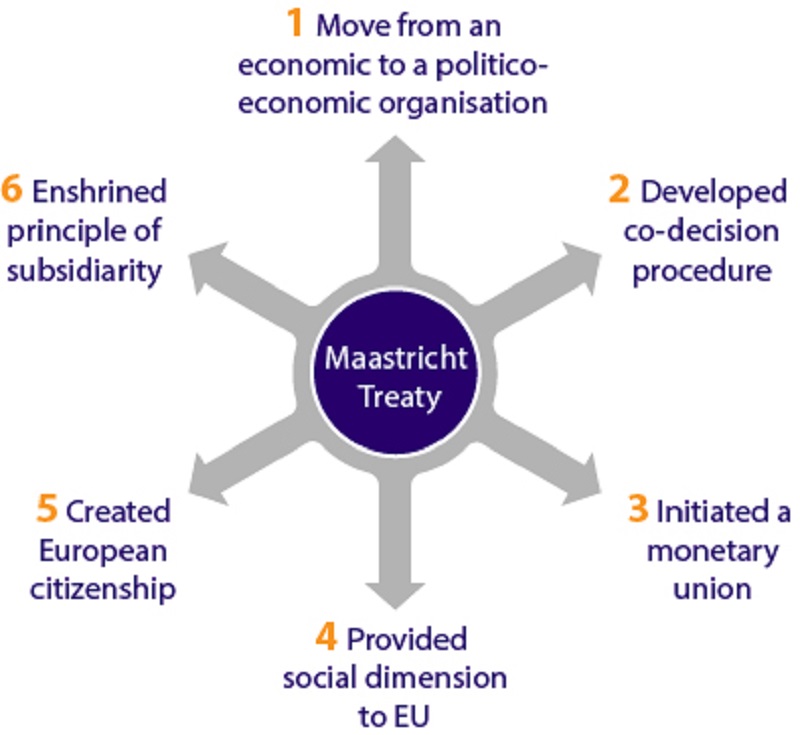

|

| The main objectives of the Maastricht Treaty [University of Portsmouth] |

The Maastricht Treaty in 1992 created the European Union, transforming economic cooperation into limited political integration. Somewhat ironically, this treaty placing emphasis on political integration stressed economic competition rather than the earlier priority on cooperation. It also introduced a package of strict fiscal and monetary rules that would lay the basis for the austerity policies after the global crisis of 2008.

The Treaty on European Union, which incorporated Maastricht, specifies the goal of creating “a highly competitive” market economy. In effect this treaty and its companion, the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, created the governance mechanisms to facilitate and enforce a neoliberal economic regime. The German economic doctrine of “ordoliberalism” provides the philosophical underpinning of the treaties. This doctrine maintains that unambiguous legal rules are required to maintain and enforce a competitive economy, especially restrictions on national fiscal and monetary policy.

British membership in the European Union was unique as a result of its various governments negotiating special arrangements or opt-outs from the political constraints on national economic policy. These special conditions loom large in the Brexit process because should the current or a future British government seek to re-enter the European Union, that might occur on less favorable terms. Maintaining those terms is a constant sub-text in the British domestic debate over whether to reverse the Brexit process.

|

| The signature ceremony of the Maastricht Treaty by the twelve Community Member States-turned-EU members in Maastricht on February 7, 1992 [AFP] |

Brexit Revolt

Voter revolt against the mainstream political agenda determined the outcomes of both the referendum on UK membership of the European Union and the unexpected collapse a year later of the Conservative government’s majority in the UK's June 2017 general election. These directly linked electoral events transformed British politics as well as unsettling politics on the continent. Prior to the referendum, the Conservative Party boasted an unassailable majority in the House of Commons, having won 330 seats compared to the Labour Party’s 232 in the May 2015 general election. Weak in numbers, the opposition Labour Party was racked by internal conflict that left the party leader Jeremy Corbyn weak and isolated. In June 2016 Labour Party MPs passed a vote of no confidence in their leader by an overwhelming majority, 172-40. Corbyn survived as due to the rules determining the selection process for leader of the party, but was severely weakened.

In late 2015 Prime Minister David Cameron pushed through Parliament an EU referendum bill, motivated by the narrow partisan goal that its success would solidify his authority over the anti-EU wing of his party. Six months later and within days of the referendum’s defeat he resigned, replaced by Theresa May who quickly demonstrated that her ambition exceeded her capacity to govern. Less than a year later she called a “snap” general election, and like Cameron did so with the confidence that she and her party would win an overwhelming victory. Instead the Conservative Party lost its majority, leaving its ability to rule dependent upon the votes of 10 MPs from the far-right Democratic Unionist Party of Northern Ireland.

The referendum on EU membership was lost because its opponents constructed a slightly larger though temporary coalition of nationalists. A few progressives voted to leave, repelled by EU austerity policies during the 2010-012 sovereign debt crisis, such those imposed on Greece. However, most on the left voted to remain while well aware of the failings of the European Union. These failings include undemocratic governance, neoliberal economic policies chiseled into the treaties, and political dominance by the largest member (discussed in Remain for Change). There can be little doubt that xenophobic fears played the largest role among those loving to leave, especially the false claim that EU membership facilitated the inflow of immigrants from Islamic countries (see photograph).

|

| Nigel Farage moved the UK Independence Party from the fringes of British politics to victory in the Brexit referendum [Reuters] |

Reversing Brexit

Legally and politically, Brexit means for the British government and population ending membership in the European Union and a need to establish a new, non-member association. Several non-member countries have formal arrangements with the EU though the specifics vary. Domestic debate rages over whether the British population will be better or worse off as a result of Brexit. Much of this debate and certainly that part that reaches the media focuses narrowly on the economic consequences, and especially the trade consequences.

Pro-EU business figures and politicians have used anxieties that Brexit might reduce British exports to campaign for nullifying the referendum result. The stronger version advocates reversing Brexit by any available parliamentary or judicial means. A second in-out referendum would be a mechanism to do this. Should this prove impossible, the fall-back option for EU supporters would be to negotiate a new relationship with Brussels that maintains existing economic rules without formal membership (sometimes called the Norway model).

Almost all British politicians who favor reversing Brexit mean by reversal a process that returns British membership to the status quo prior to the June 2016 referendum. As noted at the beginning, British membership conditions have been substantially different from those of other EU members, and by most judgments more favorable. The two most important special conditions were a reduction in the British government’s contribution to the EU budget (negotiated by Margaret Thatcher in 1984), and exclusion from the treaty obligation to replace the pound with the euro. The second is more important than the first, because in practice it means that the strict budget rules in EU treaties and the so-called Fiscal Pact cannot be enforced on a British government. Denmark is the only other EU member with this exclusion.

At present it is unlikely that any British government, Conservative or Labour, alone or in coalition, would reverse Brexit. Remainers in the Conservative Party lack the strength to remove the current prime minister and replace her with a supporter of EU membership. It is possible the current Conservative government will not keep its fragile parliamentary majority until 2022 by which date a general election must occur. If there were an election before the formal end of EU British membership, and Labour were to win, the leader of the Labour party, who would become prime minister, has repeatedly stated that he would not support a Brexit reversal.

|

| British prime minister Theresa May and EU Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker in Brussels, December 4, 2017 [European Commission] |

It is the hope of British supporters of EU membership that a combination of public opinion and economic calamity will bring about Brexit reversal either through a policy change by the current government or the election of a Labour government and a re-formulation in its official position. These political shifts seem unlikely to occur. Essential to assessing the credibility of the Remain campaign to win public opinion is to identify the practical steps in Brexit reversal. The first step in that identification is clarifying the formal status of Brexit.

In early December 2017 UK Prime Minister Theresa May reached a “phase 1”, “significant progress” agreement with the European Commission, the agency responsible for negotiations on the EU side. Much of the media and most UK politicians, both pro- and anti-EU criticized the ambiguities and lack of clarity over key issues in the phase 1 agreement. Along with the skepticism went warnings that “phase 2”, involving trade negotiations, would prove considerably more difficult. Valid as the skepticism may be, it misses the most important aspects of the December Agreement.

Important EU negotiations pass through a stage of ambiguity and lack of clarity prior to reaching definitive agreement. Media commentators frequently refer to this as “fudging” or “kicking the can down the road” in EU negotiations. Those pejorative terms indicate a misunderstanding of the EU agreement-making. In practice, the procedural ambiguities are necessary for reaching a consensus – unanimity -- among the many EU governments.

The heads of the 27 member governments endorsed the European Commission’s “sufficient progress” decision at the European Council meeting on 15 December. The agreement comes as bad news for those who would keep Britain in the European Union. Central to domestic support in Britain for reversing Brexit is maintaining Britain’s pre-referendum membership status. Maintaining that status, with its country-specific agreements, need involve no complex negotiations, instead a mutual agreement to return to what might be called “the status quo ex ante”. This “back to square 1” agreement would be immeasurably simpler than re-application for membership as required in Article 49 of the Lisbon Treaty (incorporated into the Treaty on European Union).

The European Council’s endorsement of “sufficient progress” in Brexit negotiations seems to close the political route for a return to the status quo ex-ante. As the president of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, put it: “It is now up to [the European Commission] to draft the withdrawal agreement with our British friends” (see video). To reinforce the no-way-back status of Brexit, several EU governments oppose beginning trade discussions before Britain is “outside” (term used by the Swedish prime minister). In another indication of the finality of Brexit, in February the European Parliament began the legislative process of re-allocating the 73 seats assigned to Britain.

That many if not most politicians on the continent consider Brexit irreversible should not surprise us. The voters of other countries have rejected EU treaties, lesser initiatives and/or joining the eurozone. However, in no country but Britain have voters explicitly rejected membership itself. Related to that, no government of an EU country has begun the Article 50 procedure for withdrawal. In two years, Conservative governments took three major and definitive steps towards leaving the Union: 1) purposefully scheduling a referendum in which voters rejected membership by a narrow margin; 2) introducing and obtaining approval for legislation of intent to withdraw under Article 50 terms (which was supported by the Labour Party); and 3) achieving agreement in the first phase of withdrawal negotiations. As a result of these unprecedented steps there is no likelihood that the remaining 27 EU governments would collectively accept British re-entry under pre-referendum conditions – i.e., no return to the status quo ex ante.

Brexit Reversal deus ex machina

The irreversibility interpretation of the Brexit process is a serious argument based on legal reasoning and not “Brexit propaganda”. However, there is legal mechanism that contradicts it. Recall that irreversibility of Brexit derives from a strictly political problem. No British government is likely to accept a re-entry process that excludes the present country-specific benefits; and the EU heads of government, the European Council, will not allow re-entry on terms more favorable than those enjoyed by all other members. The solution to this apparent dilemma from the British side is finding a basis for unilateral reversal of Brexit with those special conditions in tact.

By some legal arguments such a solution exists. Britain and the EU are parties to international treaties that affect the Brexit process. Constraints imposed by extra-EU treaties have already played a role in the Brexit negotiations. Examples are International Labour Organization conventions that EU governments have adopted and human rights provisions of the Council of Europe (which is not an EU institution).

An international agreement relevant to Brexit is the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, adopted in 1969 and ratified by governments of 115 countries including EU members. Articles 65-68 of the Vienna Convention include the provision that any notification of intended exit from a treaty can be revoked at any time before it becomes legally effective. By activating Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union, the British government gave notice of intention to exit the EU. The Article 50 legislation was not a legal commitment to exit. Should a member country complete the exit process, Article 50 allows for re-entry through re-application, as specified in the previous article of the treaty. Article 50 does not mention the possibility of a government revoking its intention to leave; “it is silent” to use a legal phrase. Since Britain and the other EU countries are parties to the Vienna Convention, it is a reasonable inference that the provisions of the Treaty on European Union such as Articles 49 and 50 do not over-ride the Vienna Convention.

When an event occurs relevant to a treaty but is not mentioned by that treaty, standard legal procedure is to refer to other legal commitments of the treaty partners to interpret the unanticipated event. This is the legal status of a unilateral decision by a British government to reverse Brexit. Moreover, reversing Brexit would adhere to the fundamental principle in international law of pacta sunt servanda (“agreements must be kept”).

It is unlikely that European Commission officials would accept a unilateral reversal of Brexit. As has been stated publicly, they fear that allowing unilateral withdrawal by a British government would give incentives for if not actively encourage irresponsible negotiating tactics by national governments across the Union. For example, the Polish government, currently subject to EU sanctions for legislation that changed its court system, might invoke Article 50 opportunistically as a negotiating tactic.

However, it is not clear if that anxiety should over-ride the right of citizens of a current member state or their government to change opinion before exit takes effect. Policy shifts frequently occur in democratic countries; indeed, facilitating electorates to change their minds represents a strength of democracies. The “right to rethink”, by its nature unilateral, also meets the principle that continuation of treaties takes precedence over their termination. This principle, favor contractus, appears in Article 68 of the Vienna Convention. On the basis of the reasons given above, the German Confederation of Trade Unions released a legal opinion that Article 50 of the TEU allows unilateral withdrawal of any exit application.

The Vienna Convention approach to Brexit has two important implications. First, because it concludes that reversal can occur unilaterally, a second British referendum is not required, though it may be politically necessary. Second, the unilateral decision by the British government would be simple reversal, not re-entry. Reversal implies no negotiations and an immediate return to the status quo ex ante. The British government would retain all its “opt-outs”, including no obligation to join the euro, financial rebate, and non-participation in the so-called Fiscal Pact.

To unilaterally reverse Brexit a British government would first pass legislation through Parliament canceling the 2016 legislation activating the Article 50 process. That would be followed by announcing an end to negotiations over Brexit conditions. From the point of view of the British government there would be nothing to negotiate, because EU membership had been reinstated. There can be little doubt that the European Commission would not accept the British government’s right to unilateral reversal. The dispute would go to the European Court of Justice where the outcome cannot be predicted.

Missed the boat

The Brexit process resulted from an unnecessary referendum on EU membership motivated by internal conflicts in the Conservative Party, an example of the Law of Unintended Consequences. As a direct result of an unnecessary referendum the Conservative government collapsed and the EU-skeptics in the Labour Party gained strength. The subsequent acrimonious debate over the Brexit process dominates political discourse and threatens to split the two major parties.

In January 2017 in an interview on Sky News, the leader of the Labour Party was asked if he supported at second referendum on EU membership, to which he replied in the negative (“the Remain ship has sailed”). Mechanisms exist by which a British government could attempt, perhaps successfully, to reverse Brexit. There is no realistic prospect of any British government invoking those mechanisms.

________________________________________

Dr. John Weeks is Emeritus Professor of Development Studies at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), founding member of "Economists for Rational Economic Policies", and author of “Economics of the 1%: How Mainstream Economics Serves the Rich, Obscures Reality and Distorts Policy”