“Day Zero” is the moment when residents of a city or region no longer have access to drinking water—when the last drop flows from their taps. First coined in Cape Town, South Africa, (1) this term is now being echoed in 2025 from Tehran, a capital with over 15 million inhabitants. Concerns about the sustainable provision of drinking water in Tehran and other major Iranian cities have reached critical levels. The gravity of the crisis is underscored by President Masoud Pezeshkian’s stark warning, “If it doesn’t rain in Tehran, we will have to ration water; if it still doesn’t rain, we may have to evacuate the city.”

Despite these alarms and the deteriorating situation in Iran, evidence suggests this crisis is not unique to Iran. Alongside reports of emptying reservoirs that supply Tehran’s drinking water and the complete desiccation of Lake Urmia, media outlets have also covered the drying of Tuz Lake—the second largest lake in Turkey—in 2023, which led to the tragic loss of over 5000 flamingos. (2) Similarly, Ankara’s drinking-water reservoir levels fell alarmingly from 32.8% to 9.3%, leaving only about three months of supply. İzmir faced a comparable situation, with its own reservoirs sufficient for only around two months. (3) Clearly, water security in the broader region has deteriorated far beyond initial expectations and has now reached a critical threshold.

Tehran, with a population of nearly 15 million permanent and transient residents, is Iran’s political, economic and foremost industrial centre. Ensuring its water supply has long been a core governmental concern. Since Tehran was designated Iran’s political capital, securing its drinking water has been a persistent governance challenge. As early as 180 years ago, Mirza Taghi Khan Farahani—known as Amir Kabir—divided the waters of the Karaj River into 84 shares (later expanded to 86), allocating nine shares specifically for Tehran’s drinking needs. This historic water right was formally documented in the “Tomarnameh-e Amir Kabir” (Amir Kabir’s Water Deed), which regulated allocation among Tehran and other stakeholders in present-day Alborz and Tehran provinces until the construction of Amir Kabir Dam. (4) (5) This historical document reveals that water transfer for Tehran’s consumption has long been a contentious issue.

The first modern efforts to address Tehran’s water demand began in 1949 with the transfer of water from the Karaj River, followed by water transfer from Amir Kabir Dam in 1963. As the problem persisted, four additional dams—the Latyan Dam (1967), the Lar Dam (1982), the Taleqan Dam (2006) and the Mamlu Dam (2007)—were constructed specifically to supply Tehran’s drinking water. Today, approximately 1.078 billion cubic metres (BCM) of water are annually transferred to Tehran from these reservoirs, meeting 70% of the city’s potable water demand. (6) (7) (8) This past summer, despite widespread environmental and social concerns, the government proceeded with the Taleqan-to-Tehran water transfer project to confront the growing crisis. Yet despite decades of such infrastructure-heavy interventions, Iran’s—and especially Tehran’s—water crisis appears only to have intensified.

Who is to blame? Nature or mismanagement?

Although official Iranian water statistics vary significantly among institutions—particularly the Ministry of Energy, the Ministry of Agriculture Jihad and the Department of Environment—official figures estimate Iran’s average annual precipitation at around 396 BCM. Of this, approximately 232 BCM are lost to evaporation through the natural hydrological cycle, and another 54.5 BCM are consumed through evapotranspiration in forests, plains and other natural uses. This leaves roughly 110 BCM as the country’s renewable annual water resources—66 billion from surface water and 44 billion from groundwater. Some studies indicate this renewable water volume has declined from about 130 BCM in 1994 to 110 BCM by the 2010–2011 water year, and further to around 100 BCM today.

While urban and rural drinking water demand represents a relatively small share of total national water consumption, it holds top priority in water policy. Any shortage or disruption in access to drinking water directly undermines urban and rural habitability and can quickly trigger public dissatisfaction and social unrest.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) publishes annual reports on water conditions and outlooks across Asia. A recurring key message in these comprehensive assessments is, “Asian countries do not suffer from physical water scarcity; what turns water shortage into a serious problem is water mismanagement.” (9) (10) In other words, water crises stem not from a lack of water, but from poor governance and mismanagement.

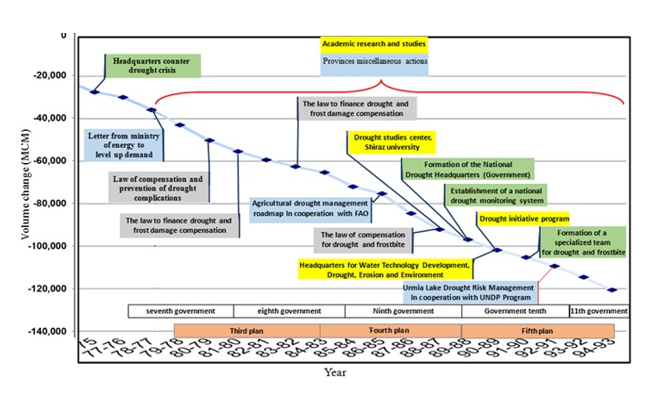

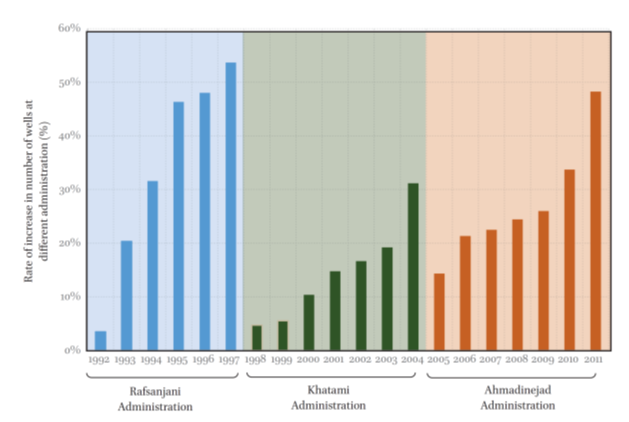

Numerous studies in Iran confirm this: despite the enactment of multiple laws and development plans, groundwater challenges have worsened. Analyses of Iran’s five-year development plans reveal that only about 30% of water-related objectives have been successfully implemented. (11) President Pezeshkian has repeatedly emphasised, “We have passed laws intending to improve the situation, but the data shows things have gotten worse. These laws haven’t solved the problem; they’ve made it worse. We must examine our own performance and ask what decisions we’ve made that, instead of fixing the situation, have aggravated it.” (12)

Yet a review of Iran’s water policies over recent decades reveals a persistent focus on supply-side and inter-basin water transfer projects—often at the expense of reforming governance and policymaking structures. These engineering-centric interventions have not only failed to resolve source-area water crises but have also triggered severe environmental consequences—such as land subsidence, dust storms and the drying of wetlands and lakes, as well as significant social and political tensions.

Development or the illusion of development? Ignoring carrying capacity and spatial planning

Integrating water management with land-use planning based on ecological carrying capacity is essential for sustainable development—especially amid growing demands and climate change impacts. (14) (15) Water issues are complex problems that deeply intertwined with economic, social, political, cultural and security concerns. Consequently, strategic development planning that ignores water realities is no longer sustainable. Water serves as a critical nexus across multiple sectors—including drinking water, food, industry, energy, environment, health and national security. Moreover, many drivers of water use originate outside the water sector itself, meaning water governance is often shaped by decisions made in other policy domains.

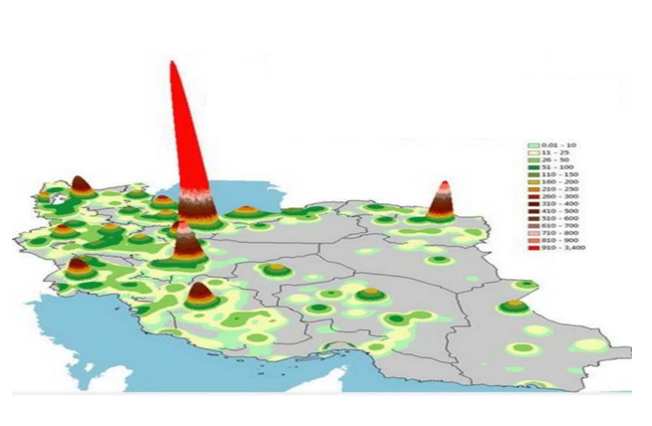

Researchers have emphasised the need to link water management with spatial planning and adopt “nexus-based” approaches that recognise the complexity of natural and human systems. (16) This led water experts to develop the “Water-Energy-Food Nexus” framework as a way to embed integrated thinking into water governance and policy. Evidence shows that urban and industrial development in Iran has largely ignored ecological and climatic carrying capacities. Unplanned urban expansion has increased water consumption, reduced groundwater recharge and accelerated aquifer depletion. Deep excavations for construction projects in major cities—including Tehran, Mashhad, Isfahan, Shiraz and Tabriz—have disrupted underground water flows, reduced soil permeability and exacerbated land subsidence, creating significant environmental and sustainability challenges. President Pezeshkian recently stated in a session of parliament. “It is clear to me that there is no capacity left to accommodate further population growth or development in Tehran, Karaj, Qazvin and their surrounding areas.”

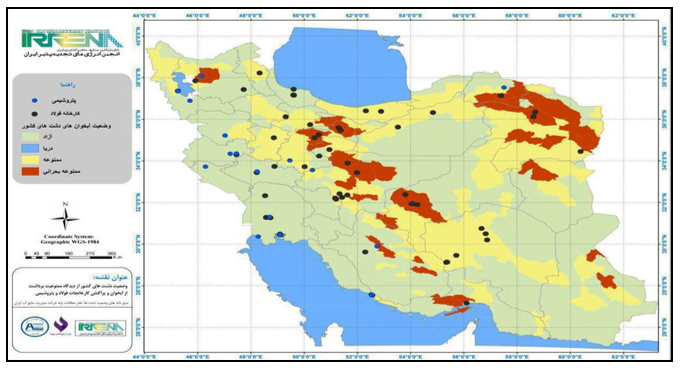

Similarly, the location of highly water-intensive industries—such as steel and petrochemical plants—in prohibited and critically over drafted aquifers has significantly worsened Iran’s water crisis, particularly in already vulnerable regions. Although President Pezeshkian has stressed the need to halt the expansion of water-intensive industries and relocate them near major water bodies, current government policy appears misaligned with this vision.

The hydraulic mission and water technocracy

A review of dominant water paradigms reveals that the prevailing ideology has long centred on dominating nature through large hydraulic infrastructure—high dams, massive water transfer schemes and mega-engineering projects. (19) This approach, often referred to as the “hydraulic mission”, treats any drop of water flowing to the sea as wasted if not captured for human use. (20) (21) Under this logic, governments prioritise building dams, canals and pumps to maximise water extraction—often disregarding environmental and social consequences. (22)

Many of today’s water and environmental crises in Iran and the region stem directly from decades of hydraulic mission-driven policies that have promoted excessive water exploitation. In this framework, water is viewed solely as a technical and engineering resource to be harnessed, while its social, political, institutional, legal, cultural and ecological dimensions are systematically neglected.

Outdated technologies

The use of obsolete water technologies in both agriculture and urban water supply is another major driver of Iran’s water crisis. For instance, Iran produces an average of 130 million tons of agricultural products annually, of which more than 30%—about 36 million tons—are post-harvest losses. Studies show that the water embedded in this wasted produce amounts to roughly 9.3 billion cubic metres per year—nearly equivalent to the total annual water consumption of Iran’s urban and industrial sectors.

In the domestic sector, evaporative coolers (“swamp coolers”) remain the dominant cooling technology across Iran, exhibiting highly inefficient water and electricity consumption. According to Technology Studies Institute, Iran currently has around 20 million such coolers, over 70% of which—per the National Standards Organisation—are rated in the lowest energy efficiency classes (E, F and G). (24)

In the summer of 2023, for instance, these coolers operated for an estimated 19 billion hours. With a typical water consumption rate of 30–45 litres per hour, they consumed between 570 million and 850 million cubic metres of water—with a midpoint estimate of roughly 700 million cubic metres—that summer alone. This volume exceeds 3–4.5 times the nominal capacity of the Amir Kabir (Karaj) Dam and equals 1.5 times the combined full capacity of the Taleqan and Karaj reservoirs. (25) In other words, evaporative coolers alone consume roughly half of Iran’s total urban 'consumptive' water use annually—despite relying on technology developed over 60 years ago.

Wastewater and inadequate water recycling

In the drinking water and sanitation sector, Iran withdraws over 9 billion cubic metres annually from its 110 billion cubic meters of renewable water resources. However, according to the National Water and Wastewater Company, only 1.7 billion cubic metres of treated wastewater was produced in 2023—just 27% of the return flow from urban water use. However, a significant portion of this treated effluent could, with proper environmental safeguards and sustainability considerations, be recycled and reused—particularly for groundwater recharge.

Moreover, non-revenue water (water lost through leaks, theft or metering inaccuracies) averages 1.99 billion cubic metres per year—accounting for 26% of the country’s total urban water supply. Some official sources even estimate this figure at 32% for 2023. These statistics highlight the lack of serious, effective measures to improve wastewater recycling and reduce distribution losses in urban water networks.

Climate change

Existing assessments confirm that climate change impacts are already directly affecting key sectors of national concern. Water and soil insecurity have undermined national food security, increased domestic production costs and imports, and exerted mounting pressure on the national budget and inflation rates. Simultaneously, declining rural and small-town resilience has driven large-scale internal migration, resulting in population concentration on the outskirts of major cities, rising demand for public services, and growing social discontent.

In the energy sector, persistent consumption patterns incompatible with climatic realities have led to chronic imbalances, periodic blackouts and industrial disruptions—ultimately eroding public confidence in the government’s ability to manage essential infrastructure.

If current trends continue without a fundamental policy shift, Iran faces deepening economic unsustainability, heightened social tensions and reduced government flexibility in implementing both domestic and foreign policies. From this perspective, climate change is no longer just a long-term environmental issue; it has become a structural threat to the country’s economic and social security. Therefore, any serious effort toward sustainable economic and social reform must begin with formally recognising climate risk at the highest levels of strategic decision-making.

Conclusion

Water functions as a coupled human-natural system, intertwined with the values, norms and identities of diverse stakeholders at multiple levels. (26) (27) As such, water systems are inherently complex; they do not recognise politically constructed boundaries, whether international or subnational. Water governance, policymaking and management are destined to fail when they prioritise artificial political borders over natural hydrological boundaries and shared stakeholder interests.

As noted above, Iran is not alone in facing water-related crises and their environmental consequences—such as land subsidence and dust storms. Cities across Turkey, Iraq, Pakistan and Central Asia confront similar challenges. Therefore, regional water and environmental security cannot be achieved through isolated national actions. Unilateral and hydraulic-mission-driven approaches that ignore natural limits and sustainable development principles are bound to fail in the medium and long term, even if they yield short-term gains for some.

The only sustainable path toward water and environmental security in Iran and the region lies in genuine regional cooperation grounded in shared recognition of natural boundaries and committed to collaborative, sustainable management of transboundary water resources.

The critical question remains is that will policymakers in Iran—and across the region—seize the current water crisis as an opportunity to fundamentally reframe water governance and policy? Can they move away from hydraulic mission approaches that disregard environmental, social, political and security consequences, and instead adopt collaborative and adaptive water strategies aimed at achieving regional water, environmental and climate security? Or will they persist with reductionist development approaches that ignore climatic carrying capacities and rely solely on supply-oriented solutions?

In this context, “Day Zero” should not be viewed merely as a threat to urban survival; it could also serve as a turning point—one that moves decision-makers from a logic of domination over nature toward one of coexistence with it. The future of water security in West Asia will depend not on the volume of water transferred across basins, but on the region’s collective capacity for adaptation, cooperation and the reframing of development grounded in ecological justice and shared responsibility.

- Elisa Savelli et al., “Don’t blame the rain: Social power and the 2015–2017 drought in Cape Town”, Journal of Hydrology, Vol. 594, March 2021, https://tinyurl.com/2t5uvsdt (accessed 31 December 2025).

- Suzan Fraser and Mehmet Guzel, “Turkey’s Lake Tuz dries up due to climate change, farming”, AP News, 28 October 2021, https://tinyurl.com/yeytwan2 (accessed 10 November 2025).

- Tural Heybatov, “Freshwater scarcity hits Türkiye as drought worsens”, News.Az, 25 October 2025, https://tinyurl.com/yc4p7bp8 (accessed 20 November 2025).

- A. Vafaeifard, “Analysis of the potential of water conflicts in the supplying catchments of Tehran’s drinking water” (in Farsi), Master’s Thesis, Department of Water Engineering and Management, Tarbiat Modares University, 2020.

- N. Khalili, “Karaj River Water Distribution Document” (in Farsi), Cultural Heritage Records Studies, Vol. 4, No. 2, 2021, pp. 38-53.

- A. Vafaeifard, “Analysis of the potential of water conflicts in the supplying catchments of Tehran’s drinking water”.

- A. Vafaeifard et al., “Mapping Stakeholders and Their Relationships in the Water-Related Conflicts between the Capital City of Tehran and the Supplying Catchments of Drinking Water”, Iran-Water Resources Research, Vol. 17, No. 4, 2022, pp. 211–228.

- M. Jafari, “Structural Factors in Analysis for Water Conflict Transformation: An Application of the Nested Theory of Conflict in Tehran and Alborz Provinces’ Water Conflicts” (in Farsi), Tarbiat Modares University, 2023.

- Asit K. Biswas and K.E. Seetharam, “Achieving Water Security for Asia”, International Journal of Water Resources Development, Vol. 24, No. 1, 2007, https://tinyurl.com/mrx3e9hc (accessed 31 December 2025).

- “Asian Water Development Outlook 2013: Measuring Water Security in Asia and the Pacific”, Asian Development Bank, 2013, https://tinyurl.com/4ctx3rx8 (accessed 31 December 2025).

- Somaye Aslani, Yahya Kamali and Hojjat Mianabadi, “Analyzing the Challenges and Obstacles to Water Policy Implementation in the Sixth Development Plan” (in Farsi), Quarterly Journal of Governance Knowledge, Vol. 1, No. 1, Winter 2024, pp. 2-24, https://tinyurl.com/4ctx3rx8 (accessed 31 December 2024).

- “Dr. Pezeshkian in the opening session of Parliament: The laws of the past four decades in the water sector have made the situation worse. At the very least, we must avoid repeating past wrong decisions. National solidarity and trust in experts are essential conditions for reforming water governance” (in Farsi), The Official Website of the President of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 2 Dey 1404 (23 December 2025), https://tinyurl.com/4rkz2shx (accessed 31 December 2025).

- S. Morid, “Review of National Efforts to Manage Drought and the Capacity to Face Water Crises,” Iran-Water Resources Research, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2018, pp. 239–252.

- Anna Hurlimann and Elizabeth Wilson, “Sustainable Urban Water Management under a Changing Climate: The Role of Spatial Planning”, Water, Vol. 10, No. 5, 25 April 2018, https://tinyurl.com/4bkrjm7x (accessed 31 December 2025).

- Prathiwi Widyatmi Putri, “Strategic Integration of Water Management within Spatial Planning” in Quartiersentwicklung im globalen Süden, ed. Uwe Altrock et al. (Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2018), pp. 309-326.

- Hamidreza Barjasteh, Seyedeh Zahra Ghoreishi and Hojjat Mianabadi, “Application of Nexus Approach in Hydropolitics of Transboundary Rivers” (in Farsi), Journal of Ecohydrology, Vol. 7, No. 3, October 2020, pp. 757–773, https://tinyurl.com/3mkb5z7v (accessed 31 December 2025).

- “Population density of rural and urban areas of Iran,” Statistical Centre of Iran, 2015, https://tinyurl.com/4hw65k6s (accessed 20 October 2025).

- “Location of Steel and Petrochemical Plants,” Iran Renewable Energy Association, 2019.

- Francois Molle, Peter P. Mollinga and Philippus Wester, “Hydraulic Bureaucracies and the Hydraulic Mission: Flows of Water, Flows of Power”, Water Alternatives, Vol. 2, No. 3, 2009, pp. 328-349, https://tinyurl.com/3688wea5 (accessed 31 December 2025).

- Ibid.

- Francois Molle, “River-basin planning and management: The social life of a concept”, Geoforum, Vol. 40, No. 3, May 2009, pp. 484-494, https://tinyurl.com/4xmdjtzh (accessed 31 December 2025).

- Seyedeh Zahra Ghoreishi, Hojjat Mianabadi and Ebrahim Hajiani, “The Dimensions of Hydraulic Mission in Turkey's Hydropolitics” (in Farsi), Iran-Water Resources Research, Vol. 16, No. 1, Spring 2020, pp. 304-331, https://tinyurl.com/42xcrbu6 (accessed 31 December 2025).

- Ehsan Nabavi, “(Ground)Water Governance and Legal Development in Iran, 1906–2016”, Middle East Law and Governance, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2017, pp. 43-70, https://tinyurl.com/57m8hdyk (accessed 31 December 2025).

- Ali Abdollahi-Nasab, Hamidreza Barjeste and Arman Khaledi, “Identifying Barriers to Water Efficiency Improvement: A Case Study of Evaporative Coolers” (in Farsi), Strategic Studies of Public Policy, Vol. 15, No. 54, Spring 2025, pp. 152-177, https://tinyurl.com/4u7fdxss (accessed 31 December 2025).

- Ibid.

- Shafiqul Islam and Lawrence E. Susskind, Water Diplomacy: A Negotiated Approach to Managing Complex Water Networks (New York: RFF Press, 2012).

- Hojjat Mianabadi, “Hydropolitics and Conflict Management in Transboundary River Basins”, February 2016, https://tinyurl.com/2yz8hz4n (accessed 31 December 2025).