After the brazen violation of international law represented by the abduction of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, tensions in the Middle East have escalated dramatically in recent weeks, prompting growing speculation about a direct clash between the United States and Iran.

It is crucial to understand why the United States has not yet engaged in military action against Iran. Washington is not hesitant because it lacks overwhelming military capability—far from it. It has hesitated because, in the case of Iran, power does not translate into speed, and speed is the currency Donald Trump values most.

The common belief in the West is that Iran is weak, overextended and just putting on a brave face. However, this belief is based on a mistaken idea: that a war with Iran would be quick, controllable, and ultimately end in a way that benefits the United States. This view is dangerously naive.

Iran has spent decades preparing not to win quickly, but ensuring that any conflict with its adversaries becomes drawn out and costly. Its strategy is not centred on territorial conquest or flashy tactical successes. Instead, it is built on endurance and the imposition of costs. Iran does not aim for a knockout blow; it seeks to draw its enemies into prolonged conflicts that drain their resources, erode political capital, and consume time—ultimately exhausting even the most powerful militaries.

This is precisely why the United States remains hesitant—and why Donald Trump, in particular, treads carefully. Trump is a gambler, but he is not suicidal. He is willing to roll the dice when he believes the odds are stacked in his favour, and the payout is immediate. Iran, however, represents a different reality: a conflict with enormous downside, limited upside, almost no plausible path to a decisive resolution, and no assurance of a clean victory.

The Simple Math of Missile Defence

Modern war between sophisticated actors is no longer primarily about weapon platforms, tactics or doctrine. It is about arithmetic. More specifically, it boils down to the exchange rate between offensive munitions and defensive interceptors—and the depth of the arsenals behind them.

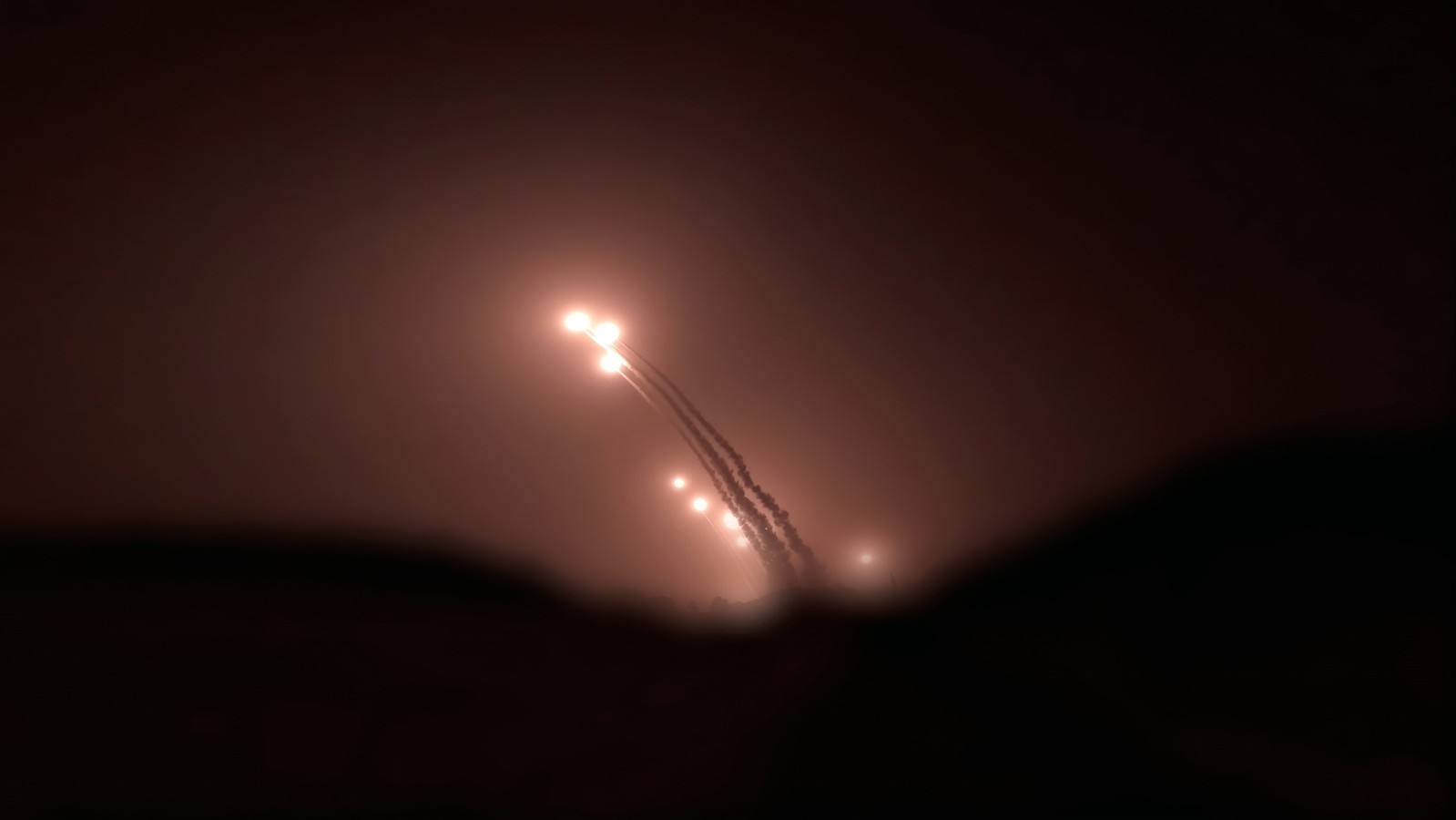

Analysts obsess over interception rates: how many Iranian missiles were shot down, or how effectively Israeli or American missile defence systems performed. But what matters is not how well defences perform on day one, but how long they can be sustained.

Ballistic missile defence (BMD) interceptors are not only expensive but also slow to produce. Offensive missiles, especially those made in Iran, are comparatively cheap and easier to produce at scale. In practical terms, a single interceptor does not guarantee the defeat of a single missile. In reality, defenders frequently fire two interceptors per inbound threat to hedge against failure. Clearly, this is problematic for the defender.

Iran understands this dynamic. Its strategy is built around exhausting missile defence systems rather than defeating them quickly. It is irrelevant whether 80 per cent or even 90 per cent of missiles are intercepted if the small percentage that gets through can inflict economic damage, close airspace or lower morale, thereby creating political pressure. Over time, the penetration rate increases because defensive resources become depleted.

The June 2025 Iran-Israel War was an example of this reality at play. Israel’s Arrow-2 and Arrow-3 interceptors were heavily expended. The United States had to step in with a backstop, deploying THAAD batteries and expending large numbers of MIM-401 Talon interceptors, alongside ship-launched SM-3 interceptors from U.S. Navy destroyers. Tactically, the defence worked. Strategically, it imposed a cost that the United States cannot afford to repeat.

The depth of an arsenal is the most critical factor in any conflict. Replenishing high-end BMD interceptors takes years. Even with the most optimistic projections, restoring U.S. THAAD interceptor stocks to pre-June 2025 levels will not occur until around 2027. This is unfolding as China continues its military buildup, where these same interceptors are vital for deterrence in the Western Pacific.

Every interceptor used in Israel is not available for other purposes. Each time missile defence assets are deployed to the Middle East, there is an opportunity cost. The United States is no longer operating in isolation; it is balancing a multi-theatre competition with limited resources.

Iran, by contrast, needs only to ensure that its offensive arsenal remains larger than the defensive inventory arrayed against it. In this respect, Iran holds a decisive advantage.

Iran’s Indigenous Ecosystem

Iran’s capabilities are frequently misunderstood because they are evaluated piecemeal. Iranian systems are designed to operate as a coordinated ecosystem—a system of systems—each component optimised for specific roles within Iran’s unique military-geographical context.

Iranian ballistic missiles, cruise missiles and strike drones are tailored to operate within Iran's specific environment, meeting its strategic needs. These systems are not designed to work alone; they are intended to overwhelm and exhaust the enemy's defences through constant, unrelenting pressure. This allows for a gradual increase in pressure as a higher percentage of munitions successfully penetrate enemy defences, ultimately paving the way for a resolution to the conflict.

The ecosystem includes ballistic missiles across multiple range classes, cruise missiles such as the Paveh family, propeller-driven strike drones like the Shahed-136, and others.

This is why dismissing Iranian drones as “ineffective” misses the point. Drones shot down still impose a cost. They tie up combat air patrols and force the expenditure of air-defence munitions. This is a form of attrition.

Ansar Allah

Yemen occupies a peculiar position in Iran’s regional strategy. From a purely military standpoint, it is too far from Israel to be an optimal platform for decisive strikes. This has led some observers to dismiss Ansar Allah’s role as marginal or symbolic. This is a mistake.

Ansar Allah's primary role is not to launch direct, decisive attacks against Israel. Instead, the focus is on maritime coercion, economic disruption and strategic harassment. The Bab al-Mandeb Strait is a narrow chokepoint through which a vast volume of global commerce flows.

Most Iranian-supplied anti-ship munitions in Ansar Allah's arsenal are optimised for range rather than payload. Their warheads are relatively small, and they are often launched in modest numbers. The objective is not to destroy warships outright, but to tie down naval assets that could be tasked elsewhere.

In effect, Yemen functions as a force in being. The mere existence of credible anti-ship capabilities compels various navies to conduct escort missions for merchant traffic. Warships are a limited resource; each destroyer sent to the Red Sea is one less available for areas like the Gulf or the Pacific. Additionally, these threats drive up insurance premiums, increasing the cost of transiting the Red Sea. As a result, some shipping companies opt to avoid the region altogether, considering the risk too high, even with escort protection for their vessels.

Endurance by Design

A common analytical mistake is to assume that escalation is binary: either Iran launches a massive, decisive strike or it does nothing. In reality, Iran’s preferred strike pattern in a prolonged conflict would likely consist of small daily launches—ballistic missiles, cruise missiles and strike drones—interspersed with periodic larger salvos.

Ballistic missile defence systems are optimised for short, intense engagements. They are not optimised for weeks of constant readiness and the resulting crew fatigue. Maintenance backlogs accumulate. Even if interception rates remain high, readiness erodes.

This logic applies equally to the Israeli and American air forces. Continuous air defence operations require combat air patrols that could otherwise be used for strike missions. Every aircraft tied down defending airspace is one less attacking Iran. Iran counts this as success.

Crucially, Iran’s arsenal is diversified precisely to sustain this tempo: ballistic missiles, cruise missiles and strike drones. Each system compensates for the others’ weaknesses. None is decisive alone; together, they create an environment in which defenders are never allowed to rest. The underappreciated fact is that wars are often decided by which side can outlast the other.

Cruise Missiles

During the June 2025 Iran-Israel War, Iranian cruise missiles did not play a significant role. However, this does not imply that they would not be influential in any future conflict involving the United States.

Cruise missiles matter because they solve problems that ballistic missiles cannot. They are cheaper substitutes for manned aircraft. They are more accurate than most ballistic missiles. They fly at low altitude, reducing detection time and defensive reaction windows. They are also well-suited for attacking infrastructure.

Iran’s cruise missile programme is the result of frustration with ballistic missile accuracy and airpower limitations. For some target types, such as oil facilities, ports and hardened aircraft shelters, accuracy matters more than destructive force.

Recent design changes suggest a maturation of guidance and launcher concepts. Cruise missiles also complicate civilian–military deconfliction. Their use almost guarantees airspace closures, imposing immediate economic costs even when interceptions are successful.

The Maritime Aspect

The Gulf, the Strait of Hormuz and the Bab al-Mandeb Strait are confined environments in which surface ships are inherently disadvantaged relative to land-based strike systems.

Iran’s maritime strike capabilities are often compared unfavourably to China’s. This comparison misses the point. Iran does not need DF-21D-type systems to create a severe risk in the Gulf. It operates in much narrower waters, against slower, less manoeuvrable targets, and at ranges where intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) constraints are far more manageable. Within this envelope, even “cruder” anti-ship ballistic missiles and anti-ship cruise missiles can be strategically meaningful.

U.S. carriers now operate hundreds of kilometres from contested coastlines. This reduces risk but also means fewer sorties, longer flight times, greater reliance on tanker support, and a heavier reliance on standoff munitions. No ships need to be sunk for this to matter.

The “‘Use It or Lose It” Problem

Israeli assassinations of senior figures—often in their homes, sometimes alongside family members—introduced a new psychological dynamic. Iranian leaders are no longer weighing abstract regime survival alone. They are weighing personal survival.

This creates a “use-or-lose” mindset. Restraint becomes less rational once escalation begins. Capabilities previously held in reserve become harder to justify withholding. A testament to this new reality is the unprecedented declaration by Iran’s Supreme National Defence Council that Iran reserves the right to launch pre-emptive strikes based on ‘objective signs of threat’.

Major General Abdolrahim Mousavi, Chief of Staff of the Iranian Armed Forces, also remarked that, following the recent 12-day conflict, Iran revised its military doctrine, shifting from a purely defensive posture to an offensive posture and delivering a crushing response to any aggression.

The Davidson Window

The United States is no longer operating in a world in which it is the only major military player. As stated earlier, every interceptor fired in the Middle East carries an opportunity cost in the Western Pacific.

The depletion of THAAD and SM-3 inventories in 2025 will not be remedied until about 2027, overlapping with the so-called Davidson window regarding China and Taiwan.

Iran knows this. Israel knows this. Trump knows this. This is why symbolic action is more attractive than all-out war.

The Axis of Resistance After 7 October

Any serious analysis of Iran’s current posture must begin with an uncomfortable admission: the strategy pursued by Iran and Hezbollah for nearly two decades failed after Hamas’s 7 October 2023 attack on Israel. That strategy—often described as “no war, no peace”—was not foolish. On the contrary, it worked for a long time. It relied on a threat of regional escalation to deter Israel while avoiding the costs of full-scale war.

For years, Israel refrained from striking many high-value Hezbollah and Iranian targets not because it lacked intelligence or capability, but because it did not want to risk a war that could devastate its economy and society. Hezbollah’s arsenal functioned as a sword of Damocles, and Iran reinforced that deterrent balance.

What broke this equilibrium was not Hezbollah’s actions, but Hamas’s unexpected success on 7 October and the psychological shock that followed. Israel went onto a full war footing in Gaza, absorbing costs that would previously have been politically unacceptable. As the Gaza war dragged on, the marginal cost of expanding the conflict northward steadily declined.

Iran and Hezbollah misread this shift. Their response—limited attacks calibrated to signal solidarity without triggering war—was strategically incoherent. They attempted to fine-tune escalation in an environment where Israel was no longer interested in calibration. The “no war, no peace” paradigm became a trap.

Israel escalated relentlessly. The bombing of the Iranian consulate compound in Syria in April 2024 should have been a flashing red warning sign. The assassination of Fuad Shukr in Beirut on 30 July 2024, followed by the assassination of Ismail Haniyeh in Tehran the next day, marked an even more dramatic turn of events. By September, the pager and handheld radio attacks against Hezbollah obliterated whatever remained of the old rules.

Hezbollah and Iran were paralysed—not because they lacked capability, but because they were trapped between two fears: the fear of all-out war and the fear of appearing impotent. Israel recognised this paralysis and exploited it. Deterrence failed not because Iran’s strategy was absurd, but because it was overtaken by political and psychological shifts triggered by mass violence.

This failure matters because it reshaped escalation dynamics across the region. The old equilibrium is gone. Actors are now operating in a far less stable environment, where miscalculation is more likely and restraint is harder to sustain.

Forward Deployment in Iraq

One of the most underappreciated shifts since early 2024 has been the growing importance of Jordan in American military planning against Iran. Iran’s strike capabilities—imperfect as they are—have succeeded in keeping most Gulf states on the fence. The threat Iran poses to their oil, gas, desalination, aviation and broader economic infrastructure is real enough to shape political behaviour.

Jordanian airbases are, for all practical purposes, as distant from Iran as Israeli airbases. Iran’s shorter-range strike munitions—those most relevant to coercing Arab states —cannot be used against Jordan.

As a result, Jordan has become the one place in the region—aside from Israel itself—where the United States can openly deploy offensive forces with relatively limited Iranian counter-leverage. American aircraft operating from Jordan can strike Iran while benefiting from distance, concentrated defences, and a compact footprint that economises scarce BMD assets.

Iran can respond through its Iraqi non-state allies, and it likely would. But that card can only be played so many times. Iraq is not Yemen, and Iranian influence there is constrained by domestic politics and Iraqi sensitivities to becoming a battleground once again.

This changing geometry helps explain why Iran has emphasised forward deployment of strike systems to Iraq. Lebanon is too close and too exposed. Yemen is too far for many systems. Iraq, on the other hand, is close enough to Israel to matter and useful for threatening American forces.

Why Airpower Alone Cannot Deliver a Decision

There remains a persistent belief that American airpower is omnipotent and can resolve the Iran problem through precision strikes: destroy missile sites, cripple production, decapitate leadership, and walk away. This belief ignores reality.

Iran’s strike systems are dispersed, mobile and increasingly hardened. Ballistic missile launchers are challenging to find and harder to destroy. Cruise missiles and drone launchers are cheap, mobile and easily concealed. Decoys further complicate targeting.

Standoff munitions are finite and expensive. Their payloads are often insufficient to destroy hardened underground facilities. Against such targets, the weapon of choice is often a heavy penetrating bomb, which is not a true standoff munition and requires aircraft to operate closer to contested airspace.

Airpower can impose costs. It cannot end the war. That is the reality Trump confronts—and seeks to avoid.

Economic Warfare

Iran’s leverage over the Arab states is often underestimated because analysts focus narrowly on oil infrastructure. In reality, Iran does not need to destroy oil fields to cause an economic catastrophe. It can close the airspace.

Civil aviation is the lifeblood of Dubai, Doha and Abu Dhabi, which are global hubs. Airspace closures—even temporary—have cascading effects: aircraft diversions, insurance spikes, stranded passengers and reputational damage. Tens of billions of dollars’ worth of wide-body aircraft sit exposed in airports at any given time.

This vulnerability explains Arab mediation efforts far better than appeals to regional harmony. These states are not neutral out of altruism. They are rational actors seeking to avoid becoming collateral damage in a war they cannot control.

The closure of civilian airspace is also one of the clearest early-warning indicators of impending conflict. Unlike ballistic missiles, cruise missiles and strike drones cannot be safely deconflicted from civilian air traffic.

Trump

Donald Trump is particularly susceptible to the hot-hand fallacy—the belief that a series of successes reflects inherent skill rather than favourable conditions.

Hitler was a gambler who mistook early successes for a sign of destiny. The remilitarisation of the Rhineland, the Anschluss, the invasion of Czechoslovakia and the defeat of France all built up the false belief that he was unbeatable. Each gamble succeeded, not because Germany was invincible, but because its opponents hesitated. These successes led to growing overconfidence. In the end, Hitler took a reckless risk by underestimating the industrial power, population strength and endurance of his enemies. His winning streak ended in catastrophic failure.

Trump’s is different, but the psychological pattern is familiar. He has experienced repeated instances in which aggressive posturing has led to concessions. He believes pressure works because it has before. The danger lies in assuming it will always work.

Iran is not like Venezuela, Libya or Iraq in 2003. It is a large, resilient country with significant military capabilities, including the largest ballistic missile arsenals in the Middle East, and institutions built to endure hardship and external pressure. Its regional reach, a culture centred on resistance and survival, means it does not have to win fast; it only needs to make sure its opponents don’t.

Trump knows how a failed military gamble can destroy a presidency. He also understands that a prolonged Middle Eastern war would shatter his narrative. This is why symbolic strikes—demonstrations of resolve without open-ended escalation—are far more attractive than full-scale war.

Conclusion

If the illusion of a swift victory is removed, what is left is a drawn-out war of attrition with no true winners. From this viewpoint, diplomacy becomes the only realistic option. The Middle East is already facing a host of issues, and any escalation into war would be disastrous for everyone involved.

Chinese military general and strategist Sun Tzu famously wrote, “When you surround an army, leave an outlet free.” This does not mean allowing the enemy to escape. Rather, as Chinese politician and poet Du Mu explains in his commentary on The Art of War, the purpose is to “make him believe that there is a road to safety, and thus prevent his fighting with the courage of despair.”

That logic applies here. Iran and the wider “Axis of Resistance” possess the means to set the region on fire, and if they believe they have nothing left to lose, there is little reason to think they would refrain from doing so. Iranian officials have hinted as much. More importantly, 2026 is a critical year for the Trump presidency. It is difficult to imagine him risking his presidency on a prolonged war in the Middle East, with its inevitable economic fallout – something that was, and likely still is, Anathema to his platform.

Trump is motivated by the desire to win and to win fast. While victory might be possible, it would come at an enormous cost, and expecting a quick, decisive outcome is unrealistic. That’s why I believe a symbolic strike—one that shows strength without causing uncontrollable escalation—is much more likely. This could be paired with increased economic and political pressure aimed at gradually destabilising Iran, much like boiling a frog.

(1) Ali Harb, “Trump's abduction of Maduro escalates concerns over potential war with Iran”, Al Jazeera, 5 January 2026, https://tinyurl.com/2wswxan5 (accessed 24 January 2026).

(2) Kayla Epstein, “Trump's seizure of Maduro raises thorny legal questions”, BBC, 5 January 2026, https://tinyurl.com/376nctnw (accessed 29 January 2026).

(3) Wes Rumbaugh, “The Depleting Missile Defence Interceptor Inventory”, Center for Strategic & International Studies, 5 December 2025, https://tinyurl.com/mtsmmmfn (accessed 30 January 2026).

(4) Thibault Denamiel, et al., “The Global Economic Consequences of the Attacks on Red Sea Shipping Lanes”, Center for Strategic & International Studies, 22 January 2024, https://tinyurl.com/4dx68nya (accessed 1 February 2026).

(5) Agnes Chang, Pablo Robles and Keith Bradsher, “How Houthi Attacks in the Red Sea Upended Global Shipping”, The New York Times, 21 January 2024, https://tinyurl.com/yex9tf2s (accessed 1 February 2026).

(6) Shahryar Pasandideh, “Many appear to be making the mistake of…”, X, https://tinyurl.com/cthzmtkb (accessed 2 February 2026).

(7) Shahryar Pasandideh, “Hizballah and Iran's strategy appear to be in tatters following…”,

X, https://tinyurl.com/3ywzpp78 (accessed 2 February 2026).

(8) Shahryar Pasandideh, “Whether or not the relevant Iranian decision-makers view…”, X, https://tinyurl.com/mr2w2fnf (accessed 3 February 2026).

(9) Sun Tzu, The Art of War, chapter 7, passage 36, translated on SunTzuSaid.com, https://tinyurl.com/29fwykm8 (accessed 4 February 2026).

(10) Roohola Ramezani, “Iran is rewriting its rules of war—and raising the stakes for everyone”, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 9 January 2026, https://tinyurl.com/3vcm6zvk (accessed 7 February 2026).

(11) “Iran Shifts to Offensive Military Doctrine: Top General”, Tasnim News Agency, 2 February 2026, https://tinyurl.com/5ccfy32e (accessed 7 February 2026).