Just after 3:15 a.m. local time on 13 June 2025, Tehran shuddered under a barrage of explosions. What began as a handful of detonations quickly revealed itself as the opening move in a meticulously orchestrated campaign against Iran’s nuclear and missile complexes. The Israeli Air Force (IAF), along with domestic saboteurs armed with kamikaze drones and anti-tank weapons, (1) initially paved their way towards the capital by suppressing parts of Iran’s air defence network in the northwestern provinces. By approximately 6:30 AM, over 200 fighter jets had attacked dozens of targets across Iran in five successive waves. The Israeli airstrikes continued for the next 12 days, totalling 1500 sorties. These attacks were executed within the framework of a massive operational plan known as "Operation Rising Lion". In response, Iran initiated its largest and most concentrated counter-strike using ballistic missiles in "Operation True Promise III". The daily launch of dozens of projectiles, amounting to over 500 ballistic missiles during this short timeframe, fundamentally altered the Israeli side's prior assessments.

To most keen observers, a head-on clash between Iran and Israel had been only a matter of time, especially after 7 October 2023, as shockwaves kept shoving the two sides toward the brink. The tension had already flared twice in Iran’s missile-and-drone salvos – True Promise I on 13 April 2024 and True Promise II on 1 October 2024; but the real breaking point came with the 12-day war.

Israel started laying the groundwork months earlier. In two pinpoint raids it gutted key components of four S-300 batteries around Isfahan and Tehran. Then, in the wake of True Promise II, it struck a pair of long-range early-warning radars near the Iraqi border, slashing Iran’s ability to see deep threats coming. All the while, the IAF cranked up its flight rhythm until the pattern became white noise to Iranian sensors.

The operation was launched precisely when part of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) missile units and the joint air defense forces of the Army (Artesh) and the IRGC were engaged in their annual military exercise. This complex operation was based on the doctrine of "Systemic Shock", designed to deliver a precise, sudden blow aimed at causing psycho-organisational collapse and disrupting the enemy's Command, Control and Communications network.

Within the framework of "Operation Rising Lion", several sub-operations were planned: the targeted assassination of high-ranking IRGC commanders—including Hossein Salami, Mohammad Bagheri, Amir Hajizadeh and Gholamali Rashid—codenamed "Operation Red Wedding"; and, in a separate operation named "Narnia", attacks were launched against several civilian scientists linked to the nuclear programme and their families in Tehran.

Israel pursued three major objectives. First, it blinded and gutted Iran’s air defences—taking out radars, runway, and SAM sites—to roll out the red carpet for the second objective: To inflict a severe blow to Iran's nuclear programme. These attacks, with the direct intervention of the United States under "Operation Midnight Hammer", targeted facilities such as Fordow, Natanz, the Isfahan Nuclear Technology Centre, and the unfinished Arak heavy water reactor. Third, it moved in lockstep to cripple the missile arsenal by torching factories and depots—an imperative that shot to the top of the list after the True Promise barrages exposed Israel’s soft underbelly. Nevertheless, even these concentrated attacks could not prevent Iran's reciprocal response.

Less than three hours after Israel’s first wave, the IRGC Aerospace Force launched its opening drone swarm around 6:00 a.m., with dozens of long-range suicide Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) streaking toward Israel. As the night of 13 June approached, coinciding with Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s first speech, Iran's initial missile attack took place at about 21:30 local time. This was merely a prelude to 22 extensive waves of missile attacks over the span of just twelve days. These missiles, unlike Iran's previous operations, targeted a wider range of objectives. In its two prior missile operations, Iran had focused solely on military targets, specifically Israeli Air Force bases.

However, the magnitude of Israel’s strikes extended far beyond military targets, encompassing nuclear facilities, government buildings, hospitals, residential areas and dense urban zones, thereby broadening the scope of the conflict. In Tehran alone, the toll on medical facilities was brutal: Hakim Children’s Hospital, Hazrat Fatemeh (S) Maternity and Children’s Hospital, Mostafa Khomeini Hospital, Shahid Motahhari Burn Centre, and Labafinejad Hospital sustained heavy damage; out in Kermanshah, Farabi Hospital was mauled. Nine ambulances and six Emergency Medical Services (EMS) stations were wrecked; the Hoveyzeh emergency post and a Kermanshah maternal-neonatal clinic were levelled. Six doctors, four nurses and four Red Crescent workers never made it home.

The targeting of civilian objectives, particularly apartments and residential homes, aimed not only at commanders, scientists and their families but also resulted in the deaths of a large number of non-combatant citizens. According to the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education, approximately 700 civilians were killed and over 5000 civilians were injured in these attacks. Among the fatalities were the names of at least 49 women and 13 children. In another instance, Israel attempted to bomb a confidential meeting of Iranian politicians present at the Supreme National Security Council that included the President and the Speaker of the Islamic Consultative Assembly (Parliament)—in the midst of the war.

This situation prompted Iran, in its defensive plan, to target not only military and security centres but also governmental and infrastructural objectives, some of which were located within urban environments. Although Iran has not disclosed the precise number of projectiles launched, Hebrew sources reported the launch of over 500 ballistic missiles – a figure ranging from 574 to 631 projectiles, which translates to an average of 40 to 52 launches daily.

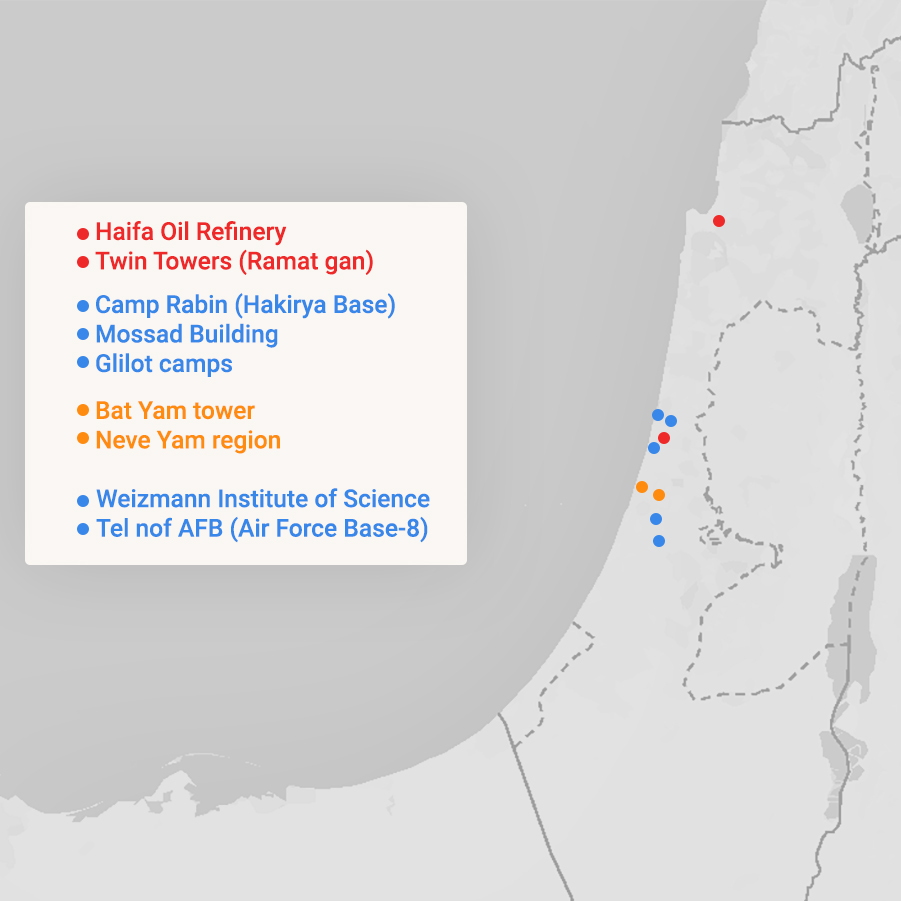

With the commencement of Iran's missile attacks, the Israeli Army Military Censor's Office, a branch of the Israeli Military Intelligence Directorate (AMAN), implemented severe measures to censor news, control information, and restrict images published regarding the outcome and aftermath of the missile strikes in both official and unofficial media. Nevertheless, the limited images and information released indicate that Iran’s targets can be categorised into three main types: military-security, economic-infrastructural, and residential areas. The most significant targeted locations are subsequently examined in detail.

Multiple news reports on Iran’s opening missile wave pointed to a strike in central Tel Aviv. The site was Rabin Camp—formerly known as Matkal-128 Camp—which comprises five core sections:

the General Staff Tower housing both the IDF General Staff and the Ministry of Defence; the Marganit Tower, which is an administrative hub for the General Staff and central communications node; the Canary Towers, home to various military offices including Air Force Headquarters; Building 22, dubbed the “Shimon Peres House” used by the Ministry of Defence and the Prime Minister’s Office; and finally the subterranean Supreme Command Post, known as “The Pit” or “Zion Fortress”, activated for General Staff operations during emergencies. Imagery released from the night of the attack shows at least one impact inside the complex. A real-time news bulletin during the strike also reported hits on the Israeli Ministry of Defence. (2) (3)

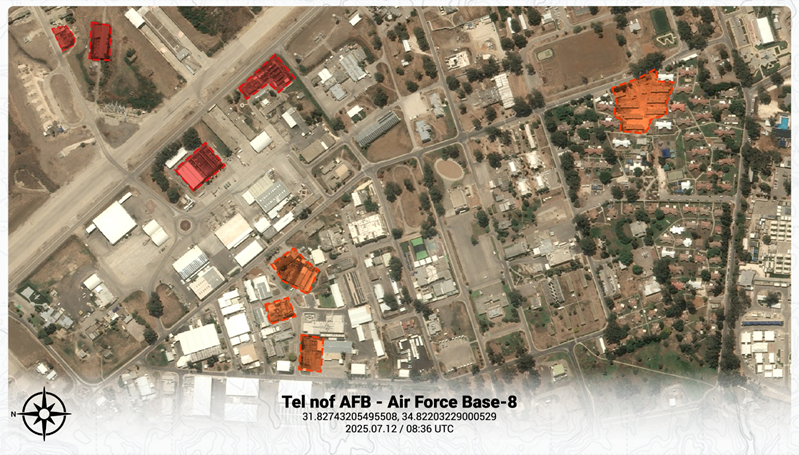

Tel Nof Airbase – Kiryat Ekron/Rehovot

Tel Nof Airbase, alternatively designated Airbase No. 8, hosts Squadrons 106 and 133 (F-15C/D fighters), Squadrons 114 and 118 (CH-53K/D heavy-lift helicopters), Squadron 210 (Eitan ISR/combat UAVs), Squadron 5601 (Flight Test Centre), Unit 555 (Airborne Electronic Warfare Centre), Unit 669 (Combat Search and Rescue), and Unit 888 (Special Forces). IDF-released footage confirms that fighters based here participated in airstrikes against Iran during Operation Day of Repentance and Operation Rising Lions. Satellite imagery acquired on 12 July 2025 reveals that, during Iran’s missile barrages in the 12-day war, at least four structures in the base’s central sector were damaged or destroyed. Closer inspection further indicates that the base’s organisational housing quarter—already struck during Iran’s True Promise II—was hit again, with at least eight residential buildings demolished and now undergoing reconstruction.

Glilot Camp – Herzliya, North Tel Aviv

The Glilot complexes, spanning roughly 2 km² at the Glilot Junction in Herzliya north of Tel Aviv, serve as the primary base for Unit 8200 of the IDF Intelligence Directorate (Aman). The site includes Herzog Camp (Military Intelligence School), Dayan Camp (military colleges), and the Intelligence Heritage Centre and Memorial east of the Ayalon Highway. Directly opposite, west of the highway, stands the Mossad headquarters. Imagery from Iran’s 17 June missile strikes on northern Tel Aviv shows at least one direct hit on a hangar within the Glilot perimeter. Despite Israeli Military Censor efforts to suppress coverage, initial photos clearly displaying Aman insignia on signage confirmed the impacted area belonged to the Intelligence Directorate.

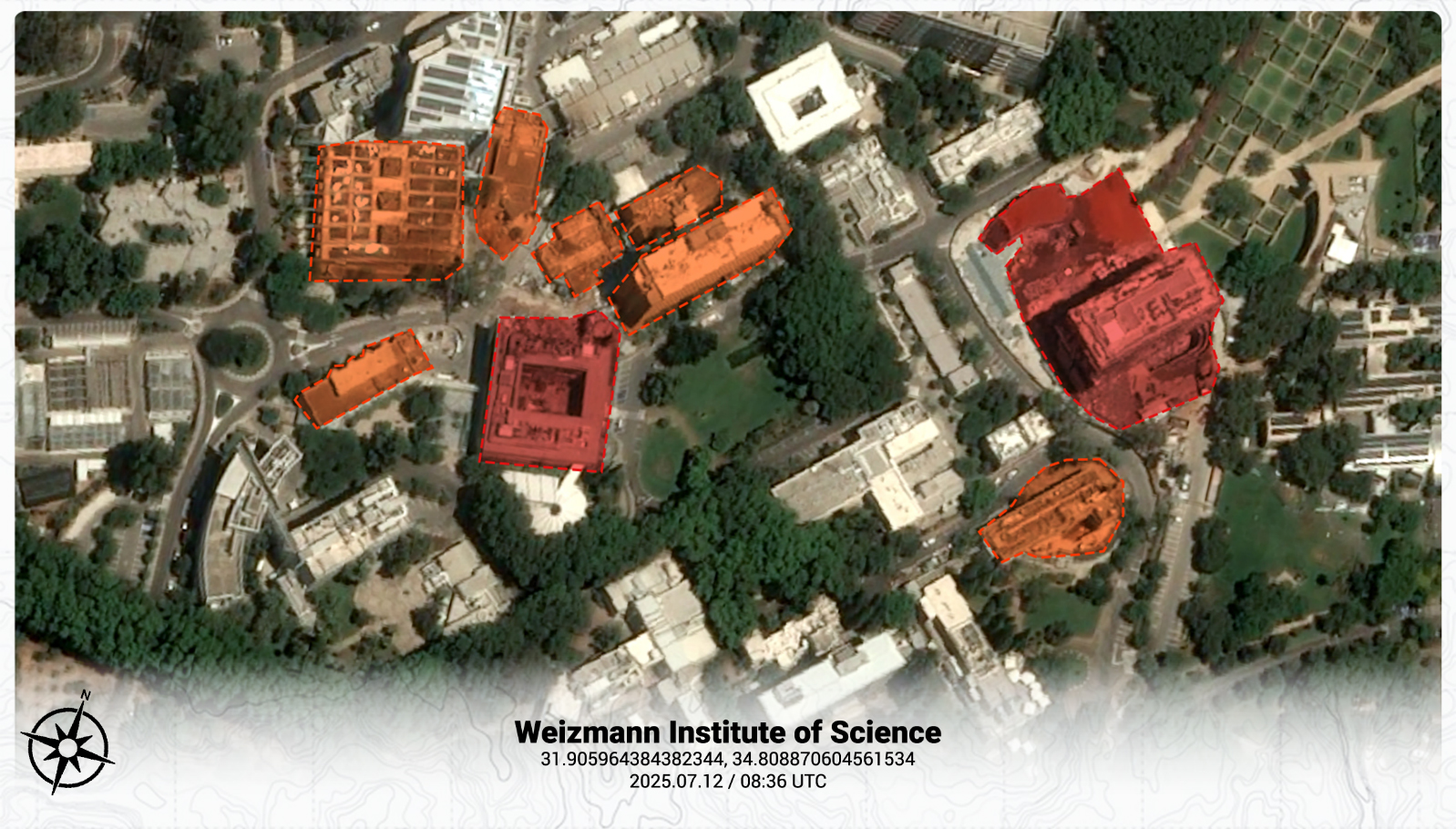

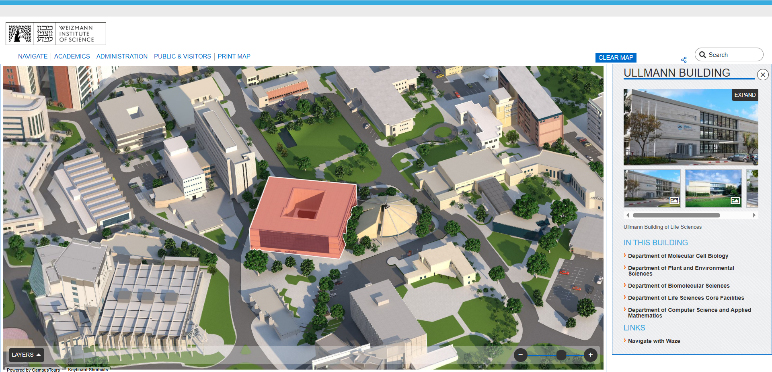

Weizmann Institute of Science – Rehovot, South Tel Aviv

The Weizmann Institute, a research-driven powerhouse, operates across mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology, and biochemistry. Beyond pure science, it collaborates on dual-use military-tech projects, including sensors, imaging systems, remote sensing and the ULTRASAT satellite—jointly developed with Elbit Systems and the Israel Aerospace Industries. Two days after Israel’s airstrikes on Iran, Weizmann came under Iranian missile fire on 15 June. Morning-after news footage and reports documented the destruction of two buildings and damage to laboratories. Satellite passes confirm direct ballistic-missile strikes on the Ullman Building (for biology) and the new Chemistry Building (under construction since 2021). Blast effects are visible on at least four additional structures: the Isaac Wolfson Building, the Wolfson Building, the Lokey Facility and the Moskowitz Building. The institute was likely targeted in retaliation for Israeli strikes on Iran’s Defence Innovation and Research Organisation (SEPAND).

Hebrew media reported (4) that the attack destroyed two buildings outright and damaged 112 others—52 residential and 60 laboratory structures. Five buildings require full reconstruction; 52 research labs and six service labs were obliterated. The strike halted 20–25 per cent of institute operations and inflicted an estimated $450–600 million in physical damage. (5)

Economic–Infrastructural Targets

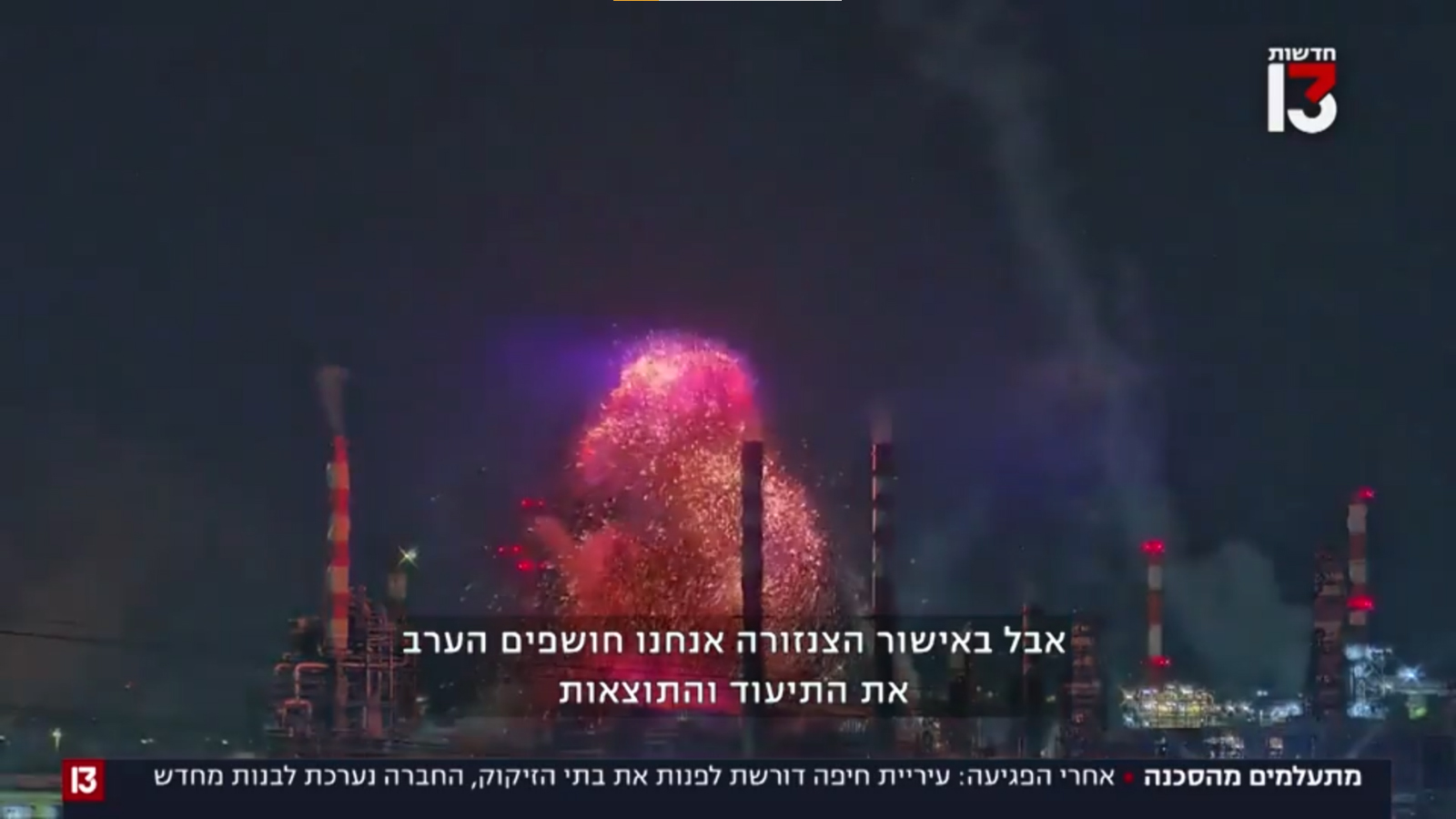

Haifa Oil Refinery

Following Israel’s 14 June airstrike on Tehran’s Shahran oil depot, Iran retaliated on 16 June with a missile barrage against the Haifa refinery. Previously owned by ICL Group, the facility was transferred to the Bazan Petrochemical Group in September 2022. Per 2024 data, Bazan supplies 65 per cent of Israel’s diesel for transport, 59 per cent of gasoline, and 52 per cent of aviation kerosene. At least three impact points were recorded inside the refinery compound. The strike killed three workers and delayed full restart until October. Hebrew sources estimated damages at $150–200 million, with only $48 million advanced from the national compensation fund. (7) (8)

Ramat Gan Twin Towers – Ramat Gan, Tel Aviv

The Twin Towers in Ramat Gan stand at the heart of Tel Aviv’s Diamond Exchange district, functioning primarily as commercial office space. During Iran’s 19 June missile wave, the Diamond Exchange district— specifically the vicinity of the Twin Towers—was struck. News reports confirmed one building fully collapsed, with adjacent structures, including the Twin Towers, sustaining blast damage. (9) (10)

Residential Areas

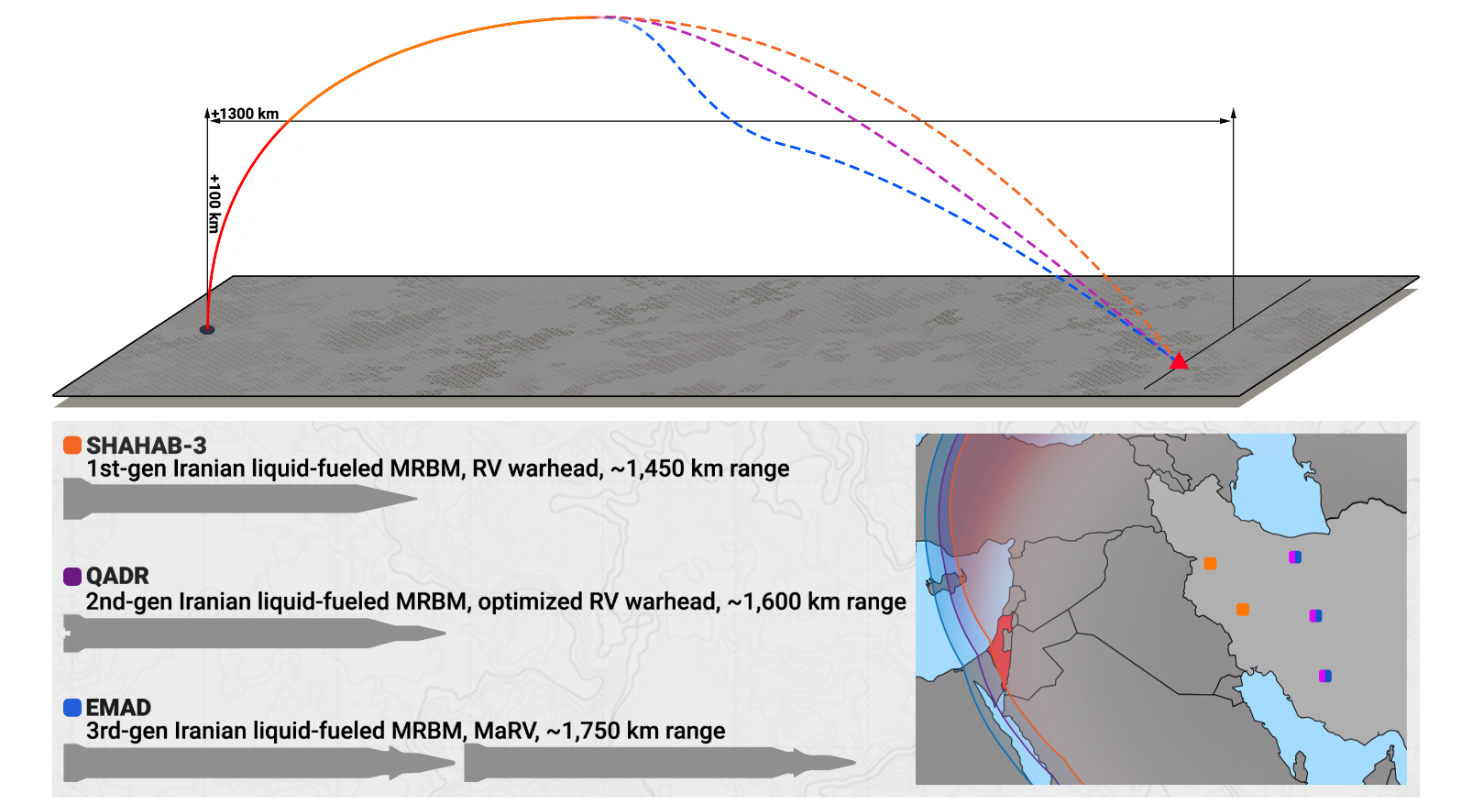

In a survey of the areas hit by Iranian ballistic missiles during the 12-day war, residential areas were also among the areas where impact marks were observed. One of the most important reasons for targeting these areas is Iran’s reliance on its older ballistic missiles. This limitation stems from the inoperability of Iran’s western bases, which host its new generation of solid-fuel missiles, forcing Iran to depend heavily on liquid-fuel missiles for its attacks.

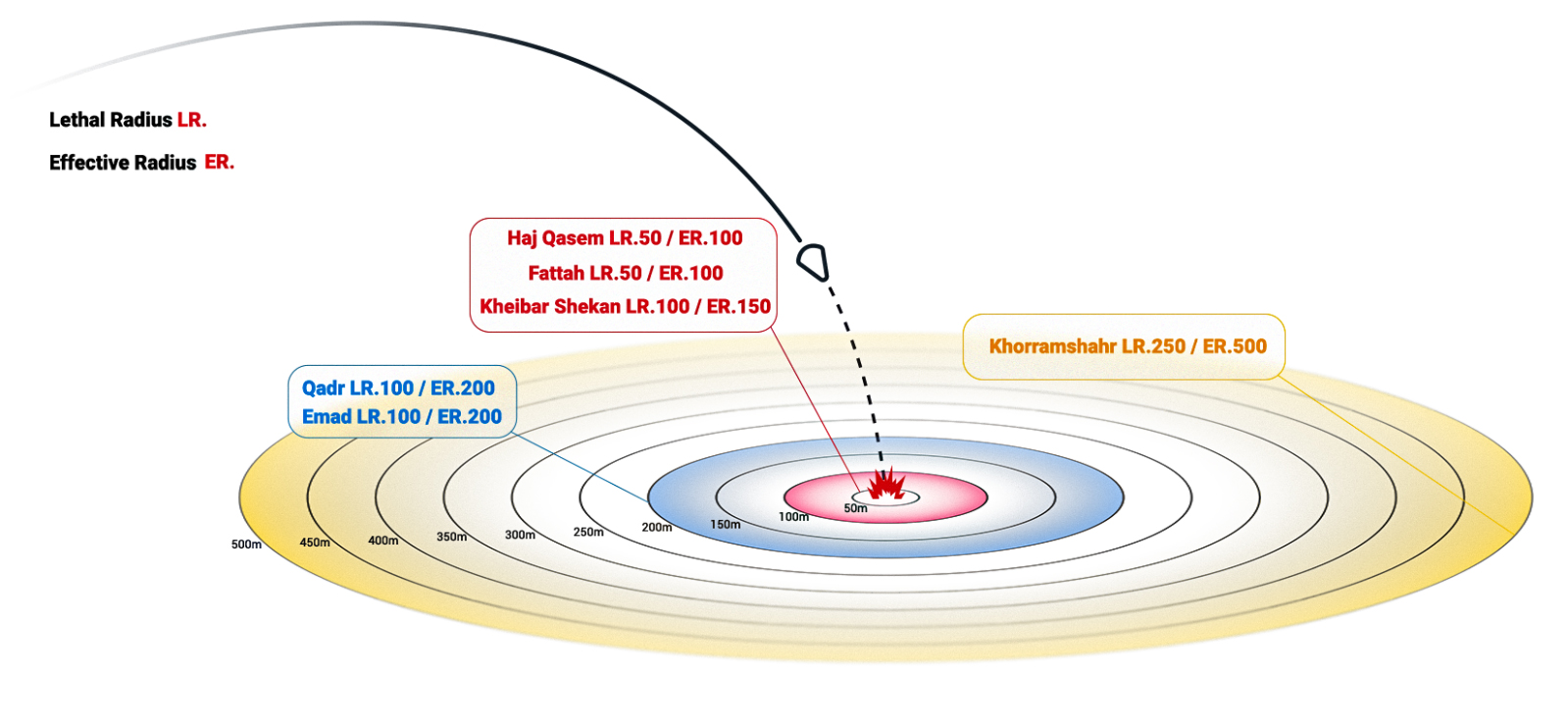

Iran's liquid-fuelled missiles have lower accuracy due to their larger Circular Error Probable (CEP) than the solid-fuelled missiles in Kehybar-Shekan and Fattah families of missiles. These missiles use a guidance system based on GPS/GNSS satellite guidance which can be disrupted with electronic warfare and lead to errors in navigation system in the terminal phase of the flight (re-entry of RV/MaRV warheads into atmosphere).

The inherent error of Iranian ballistic missiles along with the deployment of some Israeli military and security areas near kibbutzim, densely populated urban and residential areas, were among the reasons why a few of the ballistic missiles hit residential areas. For example, we can mention the deployment of Israeli anti-ballistic air defence launchers in the Rabin camp located in the HaKirya area in central Tel-Aviv. Based on the published images of the first wave of Iranian missile attacks on Tel-Aviv on the evening of 13 June, which resulted in at least one hit, the deployment of defence system launchers in central Tel-Aviv and nearby residential areas is clearly visible.

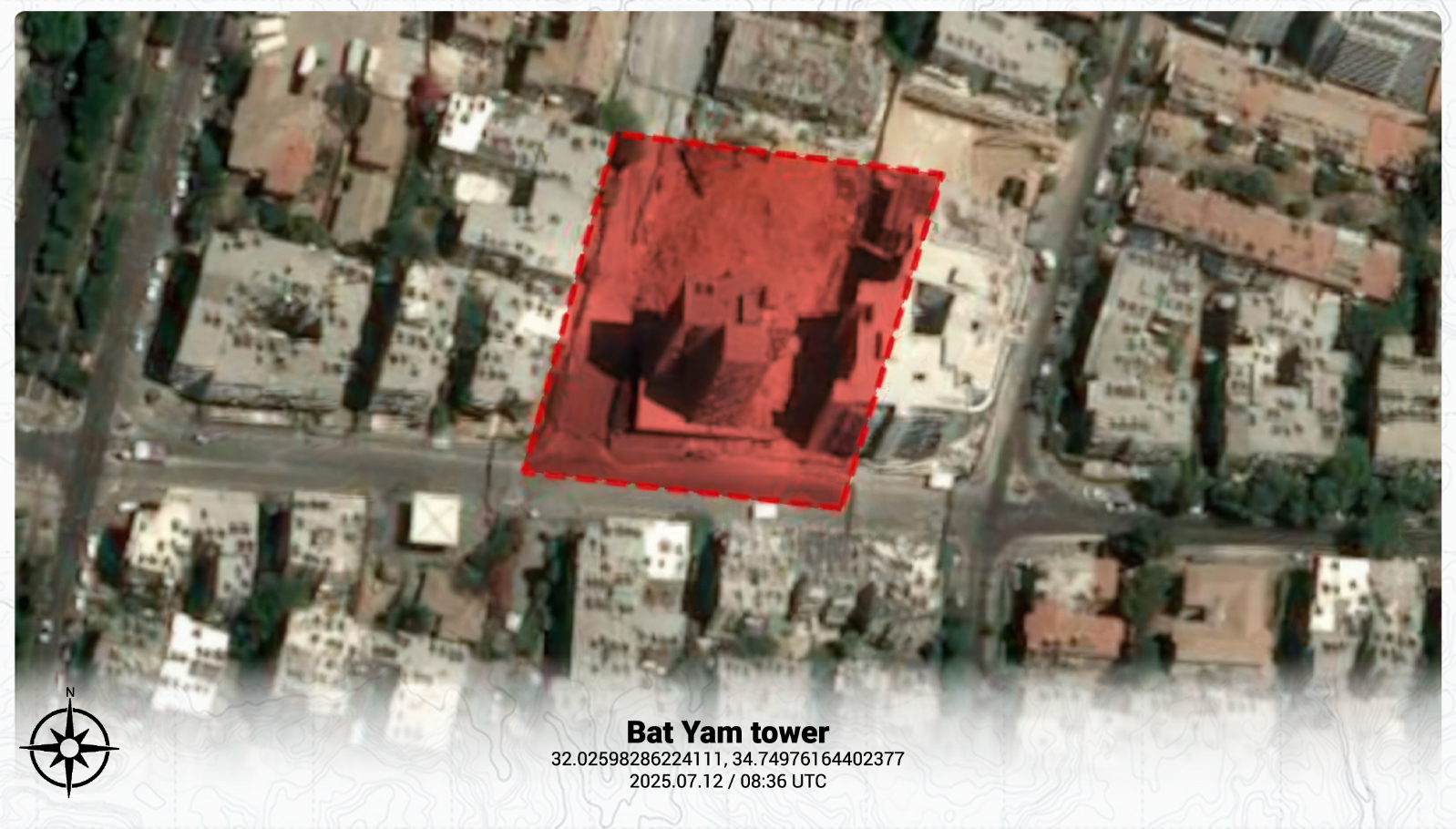

11-Storey Building – Beit Yam, Tel Aviv

On the night of 15 June, central Israel—including Tel Aviv—came under Iranian missile fire. In Beit Yam, south of Tel Aviv, ballistic-missile impacts demolished an 11-storey residential tower and a neighbouring four-storey structure, killing at least seven people. Satellite imagery from 12 July clearly shows the rubble footprints of both buildings. (11)

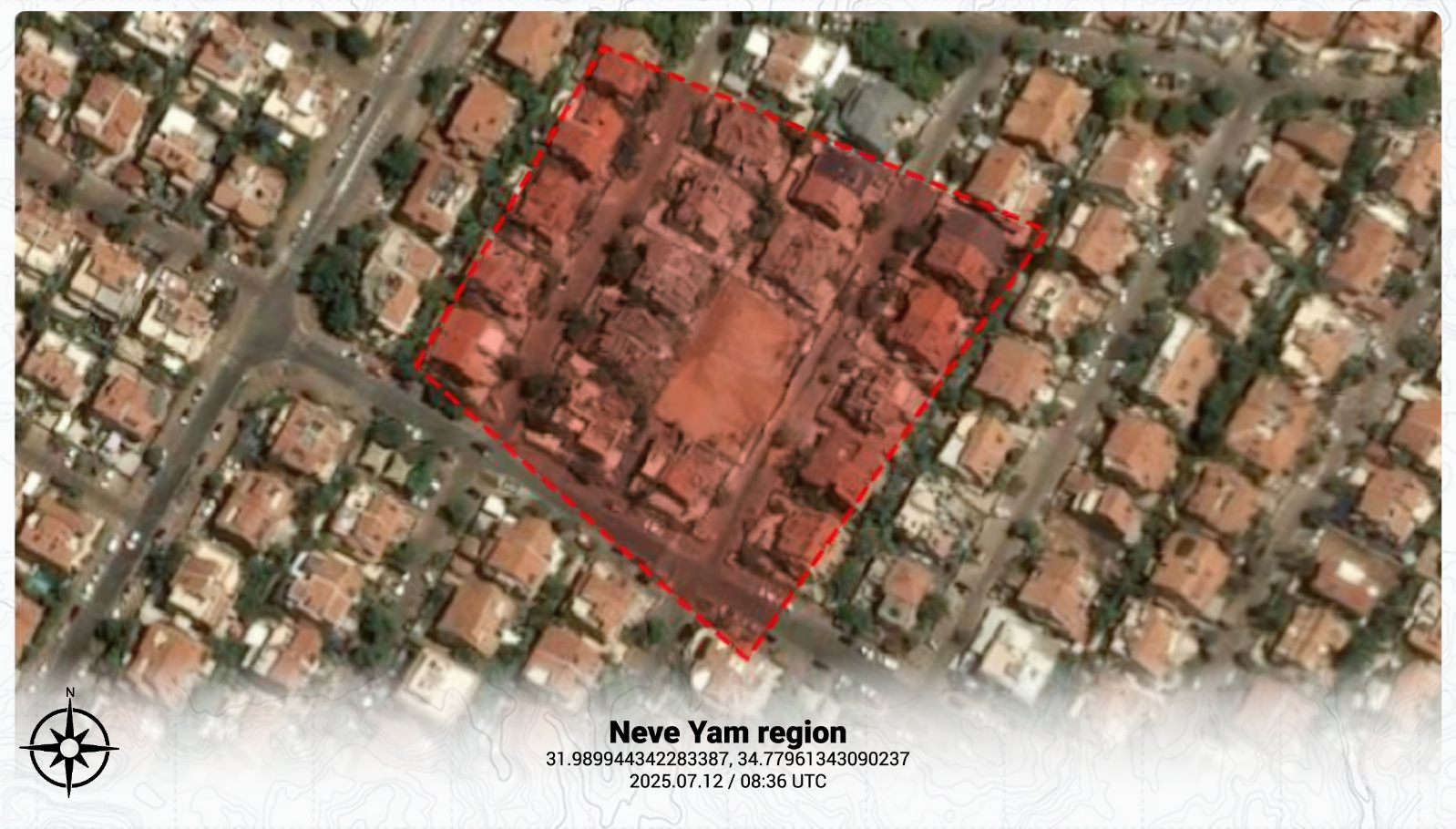

Nev Yam Neighbourhood – Rishon LeZion, South Tel Aviv

The Nev Yam residential district in Rishon LeZion—Israel’s fifth-largest city with over 250,000 inhabitants as of 2023—was struck on the evening of 14 June. Footage from the attack and satellite passes dated 12 July reveal two buildings in Nev Yam obliterated by direct hits; their debris has since been cleared. Additional news imagery documents blast damage of varying severity to at least 11 surrounding structures. (12)

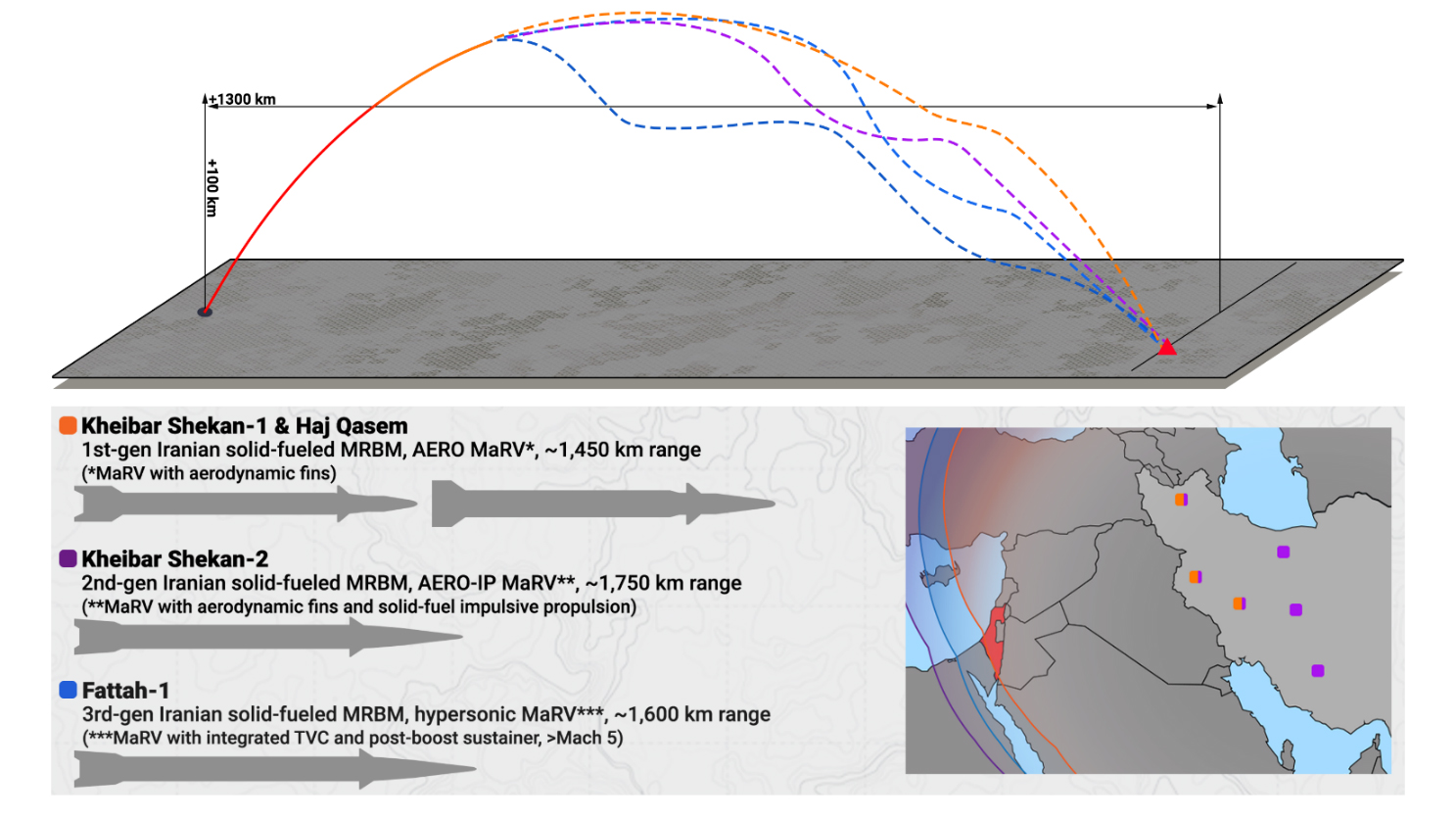

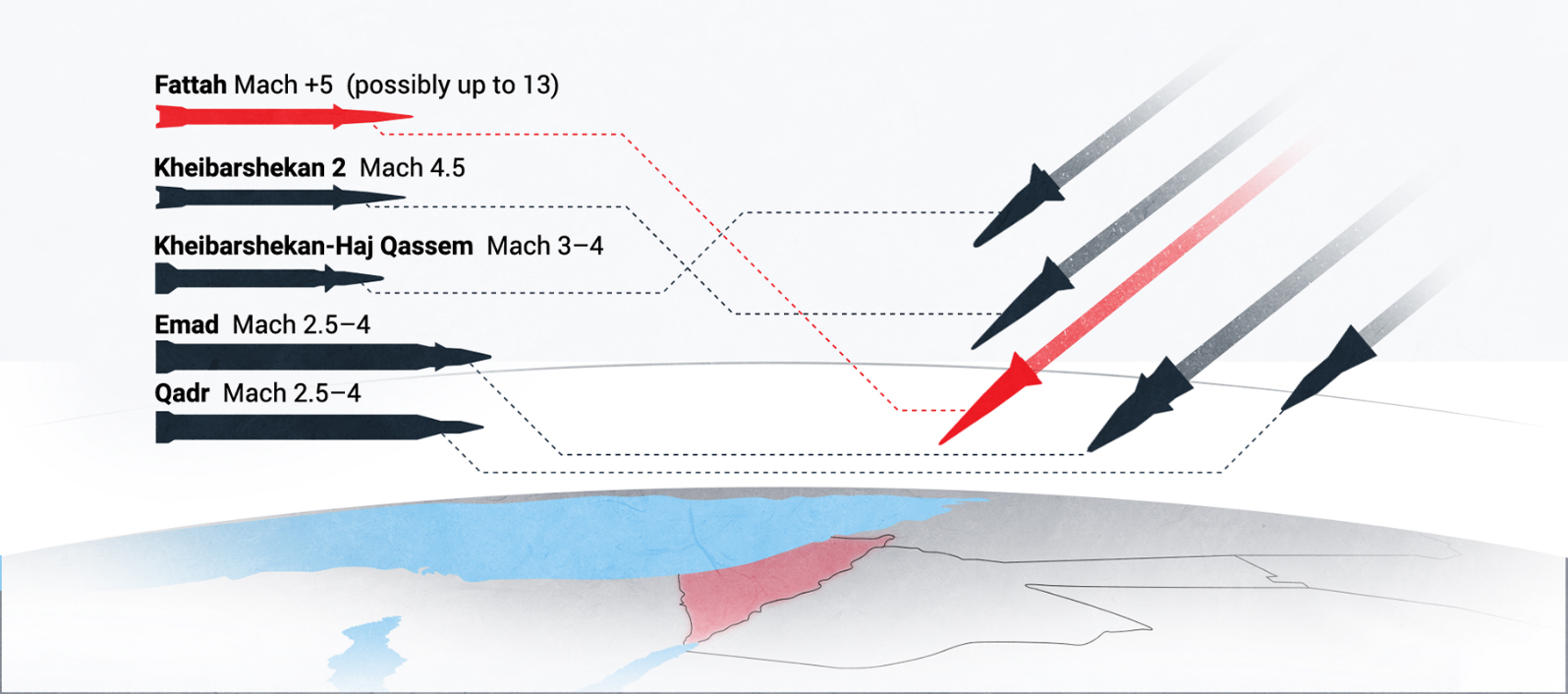

One of the prominent features of the war was the unexpected mix of Iran's ballistic missiles. Most of the launches relied on liquid-fuelled missiles and the older generations of the Ghadr and Emad systems—examples based on the Shahab-3 platform. The Ghadr family, featuring a simple separated warhead (RV), was unveiled in 2009; and the Emad, equipped with a manoeuvrable separated warhead (MaRV), was unveiled in 2015. Furthermore, another optimised version was introduced in 2023. Compared to modern generations like the Haj Qassem and Kheibar Shekan systems, these systems have a larger footprint, lower precision, slower speed and a higher failure rate, making them easier for the defender to intercept.

This challenge emerged as Iran's modern long-range inventory was primarily deployed in its western, southwestern and northwestern bases. Drawing on prior experience, Israel repeatedly struck missile sites in the border provinces of West Azerbaijan, Lorestan, Kermanshah and Khuzestan—home to more than ten facilities stocked with newer systems. Continuous Israeli aerial patrols enabled launcher identification, destruction of tunnel entrances and disruption of supply routes. While most underground vaults remained intact, disabled access points effectively sealed them off.

In practice, after the fourth day, the brunt of missile launches shifted to central and northern depots in Isfahan, Tehran, Fars and Qazvin provinces, which were largely equipped with older but still long-range missiles. A limited number of advanced systems—such as the Kheibar Shekan-2 and Haj Qasem—were employed with extreme selectivity. The pattern involved saturating defences with simultaneous volleys of liquid-fuelled ballistic missiles while reserving scarce solid-fuel precision weapons for high-value, time-sensitive targets.

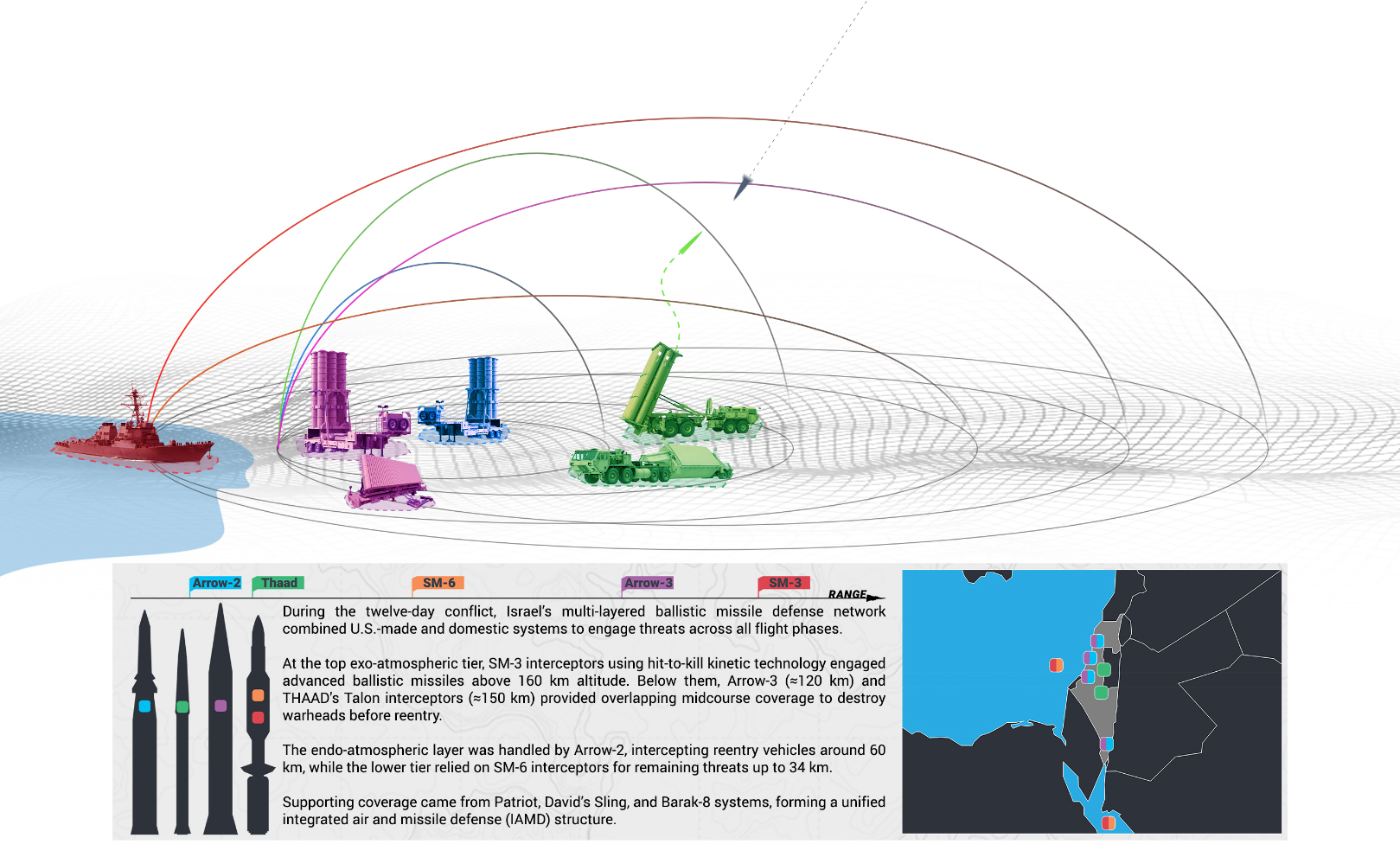

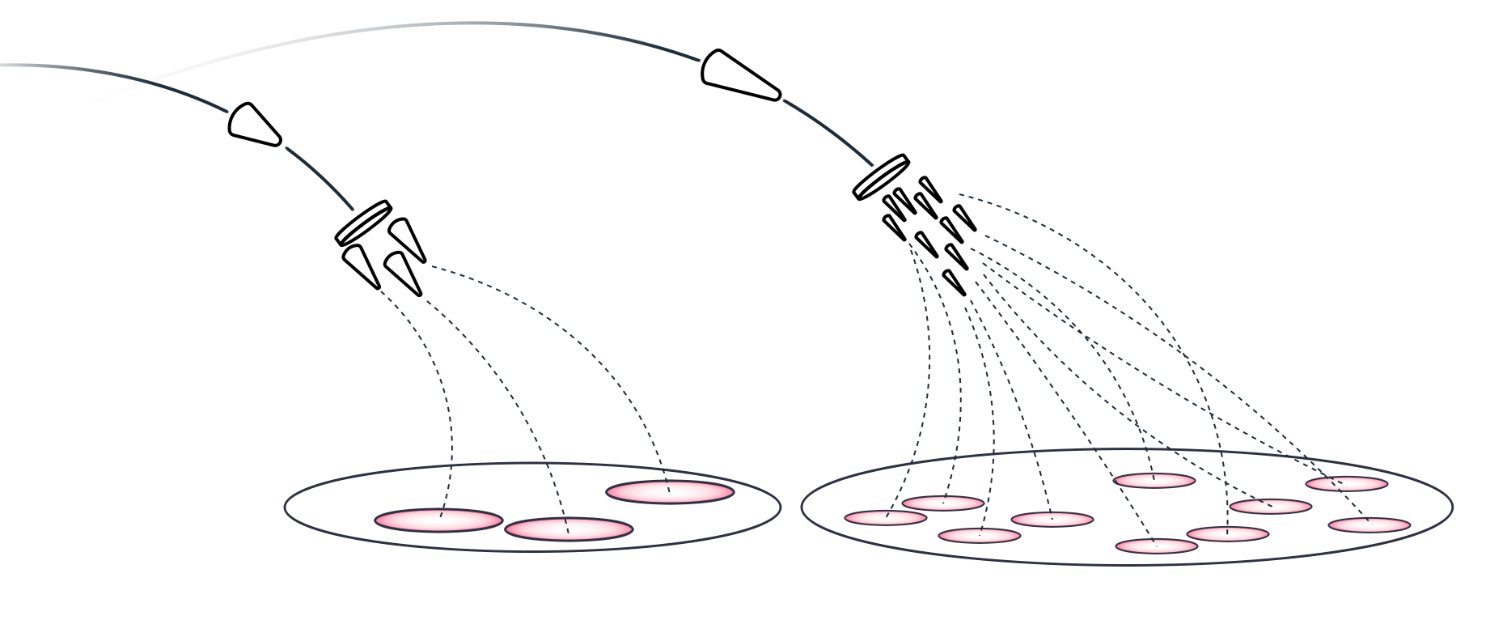

While Iran was unable to fully leverage its capabilities, Israel's anti-ballistic missile network had been unprecedentedly bolstered. During the conflict, the United States and Israel demonstrated extensive cooperation in intelligence, command, operations and integrated missile defence. As Israeli interceptor stockpiles dwindled against Iran's heavy attacks, Tel Aviv's reliance on American defence systems increased. Estimates suggest that the United States fired over 230 anti-ballistic missile interceptors to defend Israel. Israel's multi-layered defence shield during this period included the exoatmospheric interceptors including SM-3, Arrow 3 and THAAD, as well as the endoatmospheric interceptors Arrow 2 and SM-6.

The steep price the United States paid in expending its finite stock of ballistic-missile interceptors underscored the pivotal role of America’s missile-defence umbrella in sustaining Israel. Bolstering Israel’s sophisticated yet capacity-constrained shield emerged as a decisive factor in the Iran-Israel war, effectively doubling Israel’s interception throughput in short order.

Estimates indicate Israel can launch up to 100 Arrow anti-ballistic missiles simultaneously. Mobile launchers and hardened concrete shelters at four known sites—Palmachim, Ein Shemer, Tal Shahar and Eilat—enable this without reload cycles. While the United States deployed two THAAD batteries in support: the first in southern Kiryat Gat before the end of October 2024, the second near Nevatim Airbase in April 2025. Each battery fields six launchers, carrying a total of 48 interceptors, and can be expanded to up to nine launchers.

According to a Wall Street Journal report, during the battle, over 150 THAAD missiles and approximately 80 SM-3 missiles were fired—a figure equivalent to the full consumption of three THAAD batteries. It is estimated that out of at least 574 ballistic missiles launched, Israel attempted to intercept 257 missiles, of which 201 attempts were evaluated as completely successful, 20 were partially successful, and 36 were complete failures. Meanwhile, the impact sites of the Iranian missiles in Israel were subjected to severe censorship.

Estimates suggest the near future could present significant opportunities for the Islamic Republic of Iran: a comprehensive overhaul of military tactics, reconstruction of missile-related industrial infrastructure, the agile modernisation of existing systems, and the operational induction of next-generation weaponry. These capabilities, however, will only achieve peak effectiveness once the air-defence network and its personnel are fully restored.

Conversely, the costly and protracted process of rebuilding Israel’s anti-ballistic shield could tilt the deterrence balance in Iran’s favor over the medium term.

According to official statements from senior Iranian leaders—including Admiral Ali Shamkhani, Representative of the Supreme Leader and former Secretary of the Supreme National Security Council, and Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, former IRGC Air Force commander and current Speaker of the Islamic Consultative Assembly—Iran had no direct combat experience with Israel prior to April 2024. Consequently, Operation True Promise I marked Iran’s first operational encounter with Israel’s air-defence arrays. From the perspective of Iran’s Armed Forces High Command, while the operation yielded valuable technical insights, its operational impact fell short of expectations. In that strike, over 150 drones and 100 ballistic missiles were launched simultaneously toward deep Israeli targets. Yet the stark disparity in flight profiles—9–10 hours for drones, ~2.5 hours for cruise missiles, and only 12–20 minutes for ballistic missiles—made precise temporal coordination between waves extraordinarily difficult. This hard-won lesson directly informed the design of subsequent operations—True Promise II and True Promise III—enabling IRGC missile command to operate with greater tactical autonomy and staggered launch sequencing, markedly improving hit rates and penetration success against Israeli defences. It appears that a significant portion of Iran's strategic assets was intentionally held back. Long-range ballistic missiles such as Sejjil, Khorramshahr-3 and Khorramshahr-4, the Shahed-238 quasi-cruise UAV, and surface-to-surface cruise missiles like Abu Mahdi and Paveh remained in the arsenal. Given the absence of range limitations on strikes deep inside Israel, this decision suggests deterrence considerations and the strategic retention of capability for potential subsequent phases of the conflict. The Khorramshahr missile family, among Iran's newest ballistic achievements, features modern navigation subsystems, advanced flight control systems, and an optimised design to overcome multi-layered missile defense systems. The non-utilisation of these missiles in the recent 12-day war can be seen as an indication of saving strategic capacity for future engagements

During the war, several facilities tied to solid-propellant production, high-explosive manufacturing, and segments of Iran’s missile-programme infrastructure came under Israeli airstrikes. The central question is whether these raids succeeded in disrupting Iran’s ballistic-missile production chain. Imagery released by media and independent analysts indicates that a substantial portion of Iranian missile assembly occurs in hardened underground complexes—most notably the Dezful ballistic-missile assembly line showcased in February 2019. In practice, this renders complete elimination of the production pipeline beyond Israel’s current reach. The trend of relocating missile production underground is poised to accelerate. While underground propellant and explosive synthesis poses formidable engineering hurdles, it will redound to Iran’s advantage over the medium term. Should production be disrupted, Iran’s existing stockpiles are assessed to be capable of sustaining multiple successive rounds of combat.

The Kheibar Shekan and Fattah—solid-fuelled, near-hypersonic missiles likely instrumental in the Haifa refinery strike—present acute challenges to anti-ballistic defences. A significant fraction of these reserves, untouched in northwestern bases, has now been dispersed to central Iran.

Israel’s defensive outlays in a comparable conflict, by contrast, are projected as astronomical and nearly unsustainable. Precise Israeli interceptor inventories remain classified, but US officials have described the situation as critical. A Financial Times report dated 15 October 2024 warned of an imminent interceptor shortfall. Former Pentagon Middle East policy chief Dana Stroul called Israel’s ammunition posture “extremely serious”. The CEO of Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI) confirmed that interceptor production lines are running three shifts at full tilt merely to partially replenish depleted stocks.

The United States fares little better. By 2025, Lockheed Martin had delivered only ~900 Talon interceptors; of these, 192 went to the United Arab Emirates and 50 to Saudi Arabia. Of the 658 remaining in US hands, ~25 were expended in exercises and ~150 in the recent war, leaving operational stocks below 500—effectively committing one-quarter of America’s eight fielded THAAD batteries to Israel’s defence. Annual production is capped at 100 units, with 12 produced in 2025 and 37 in 2026. Full replenishment would take over 18 months and could delay foreign orders, such as Saudi Arabia’s 360-missile contract. The US Navy’s Aegis fleet fired ~80 Standard-3 missiles in the campaign. Through 2024, only 398 SM-3s had been delivered to the Navy. From 2023 to January 2025, over 400 projectiles—including 120 SM-2s, ~80 SM-6s, 20 SM-3s and assorted ESSM—were expended against Houthi drones and missiles. Adding 12 SM-3s in True Promise II and 80 in True Promise III, ~23 % of total SM-3 inventories have been consumed. With a 700–900 km engagement envelope, the SM-3 remains one of the few US tools against nuclear intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs).

In any future clash, should the United States fail to sustain an effective defensive canopy over Israel, damages would unquestionably multiply.

- Yossi Melman and Dan Raviv, “Israel Secretly Recruited Iranian Dissidents to Attack Their Country From Within”, ProPublica, 7 August 2025, https://tinyurl.com/4tcfkuj4 (accessed 17 December 2025).

- “Air raid sirens sound off as Iran begins retaliation on Israel” (Video), Fox News, 13 June 2025, https://tinyurl.com/36t2p29z (accessed 17 December 2025).

- “Trey Yingst details ‘unspeakable’ escalation in Israel-Iran tensions” (Video), Fox News, 13 June 2025, https://tinyurl.com/u9ynj4zj (accessed 17 December 2025).

- Shahar Ilan, “מכון ויצמן מצמצם בחצי את מספר תלמידי הרפואה בעקבות נזקי טילים [The Weizmann Institute Halves the Number of Medical Students Due to Missile Damage]”, Ynet, 13 August 2025, https://tinyurl.com/4x7hh4yz (accessed 17 December 2025).

- AP Archive, “Israeli scientists reel after Iranian missile strikes premier research institute”, YouTube, 24 June 2025, https://tinyurl.com/3zs8dnaa (accessed 17 December 2025).

- Interactive map of the Weizmann Institute Campus, Weizmann Institute of Science, https://tinyurl.com/whkw4uyc (accessed 17 December 2025).

- Matan Khudurov, “אחרי הפגיעה: חיפה דורשת לפנות את בתי הזיקוק, בזן נערכת לשקם [After the Hit: Haifa Demands Evacuation of the Oil Refineries, Bazan Prepares to Rebuild], 13tv, 23 July 2025, https://tinyurl.com/5n86jx7p (accessed 17 December 2025).

- “Haifa oil refinery partly reopens after shutdown caused by deadly Iran strike”, The Times of Israel, 29 June 2025, https://tinyurl.com/336cyw67 (accessed 17 December 2025).

- “Buildings damaged in Ramat Gan following Iranian attacks” (Video), The Washington Post, 29 June 2025, https://tinyurl.com/mwt9hd55 (accessed 17 December 2025).

- Associated Press, “Scenes from central Israel after Iran missile strike”, YouTube, 19 June 2025, https://tinyurl.com/s6c2a723 (accessed 17 December 2025).

- “Israel begins demolishing buildings hit in 12-day war with Iran” (Video), EuroNews, 10 July 2025, https://tinyurl.com/46zb32c7 (accessed 17 December 2025).

- Maayan Lubell and Parisa Hafezi, “Israel says attacks on Iran are nothing compared with what is coming”, Reuters, 14 June 2025, https://tinyurl.com/4vz9afuj (accessed 17 December 2026).