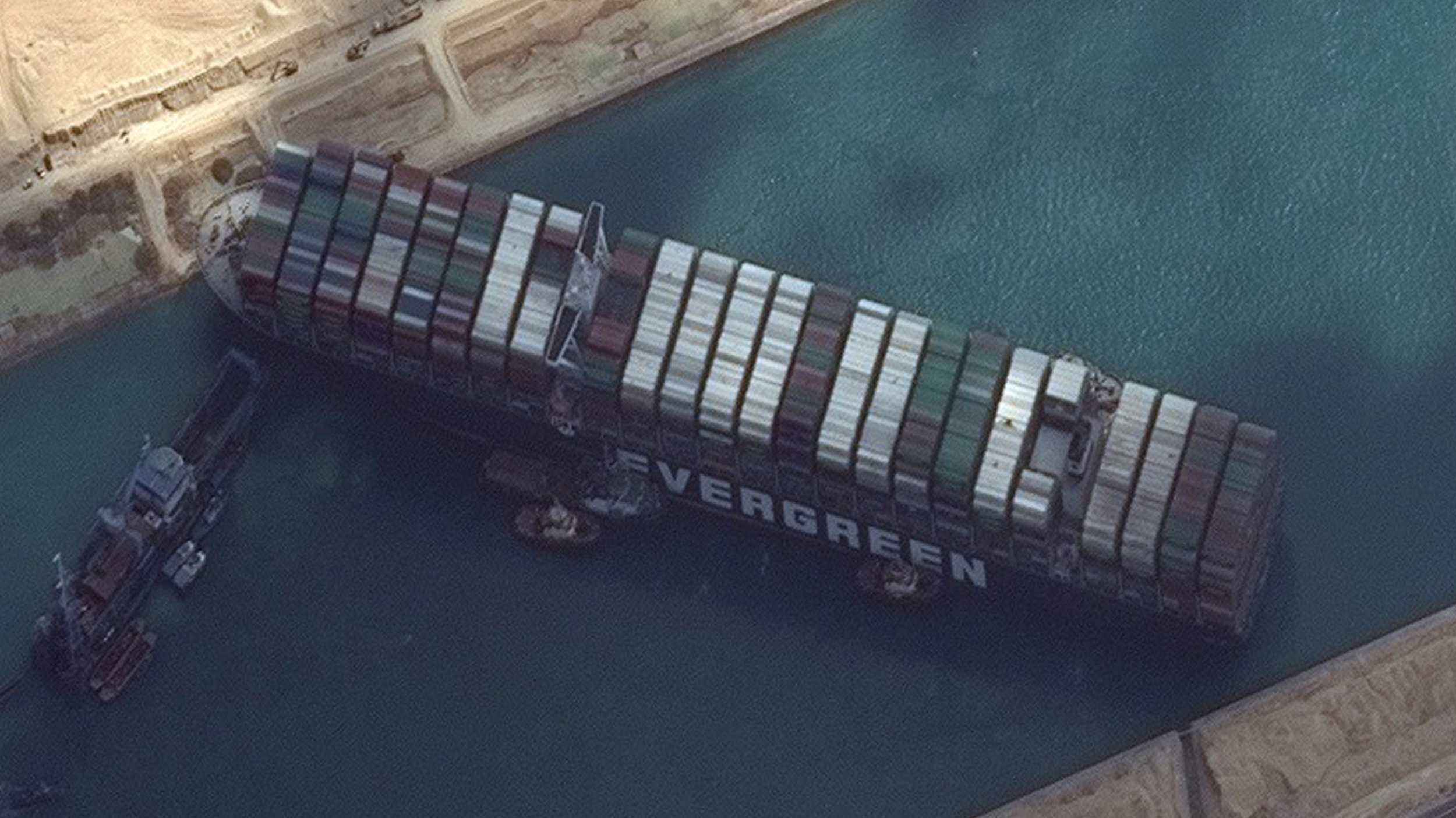

In the early morning hours of 23 March 2021, the Ever Given, a large container ship, ran aground while transiting the Suez Canal, bringing all traffic to a halt for six days before it was finally set afloat thanks to the assistance of Smit, a Dutch salvage firm. The ship was stuck in the southern, narrower portion of the canal, which had not been touched in the much touted canal expansion project in 2014. The importance of the Suez Canal for global trade and Egypt’s economy was made clear as ships were forced to reroute around the Cape of Good Hope and a significant Egyptian revenue stream was interrupted. The incident also highlighted the fragility of this crucial link in the global supply chain, putting efforts to find alternative shipping routes back under the spotlight.

The Suez Canal has been a vital waterway since it opened in 1869, but more so today than ever before. While the canal has been shut down several times in the past, interruptions to shipping traffic are felt more acutely today because global trade has increased exponentially over the past few decades. More than 12% of this trade now moves through the canal. East Asia’s rise as the principal site of global manufacturing has lent the canal even greater strategic significance, as many essential inputs for manufactured goods must head east before the finished goods flow west.

The Suez Canal is just as important for Egypt, providing much needed revenue and hard currency since its nationalisation in 1956. It also boosts Egypt’s weight on the global stage and acts as a strategic barrier against potential threats from the east of the country. It is an essential part of Egypt’s national identity as well. Not only did an estimated 150,000 Egyptians die digging the waterway, the quest for control of the canal was an engine for the national independence movement.

The long closure of the canal from 1967 to 1975 prompted various parties to search for alternatives. Of course, there is the natural alternative route, one used during the most recent closure and in past episodes: circumvention around the Cape of Good Hope. But this adds some 15 days to a ship’s journey and the extra time means higher costs.

Regionally, various projects have been proposed over the years that would connect the Mediterranean to the Arabian Sea through the Levant or Iran, using a combination of existing waterways like the Euphrates River and railroads. But these projects are not feasible because the logistics are complicated and they require security and stability in transit countries. Moreover, they could not absorb the magnitude of trade that moves through the Suez Canal.

The Suez Canal’s most serious competition comes from Israel, which has devised ideas for multiple projects to link the Gulf of Aqaba with the Mediterranean. A pipeline network between Eilat and Ashkelon was built several years ago, and there are increasing signs that this may be the preferred option of Arab oil producing states that have recently normalised ties with Israel, or will do so soon, although capacity must be increased to accommodate Gulf oil producers. There has also been talk of a canal linking the Red Sea to the Dead Sea, which would be connected to the Mediterranean by either railroad or another manmade canal. Finally, plans have been made for a rail line between Eilat and Haifa, a significant part of which has already been built. This project may receive a boost from the massive investment agreement recently signed between Israel and the United Arab Emirates.

Whatever the feasibility of these alternatives, the Ever Given incident showed Egyptians that the centrality of the Suez Canal is not necessarily a fact of nature. Many competitors, both friend and foe, are working to find alternative shipping routes. If Egypt does not take action to maintain the canal and make it more attractive, it could give these competitors the opportunity to make their projects a reality.

*This is a summary of a policy brief originally written in Arabic, available here.