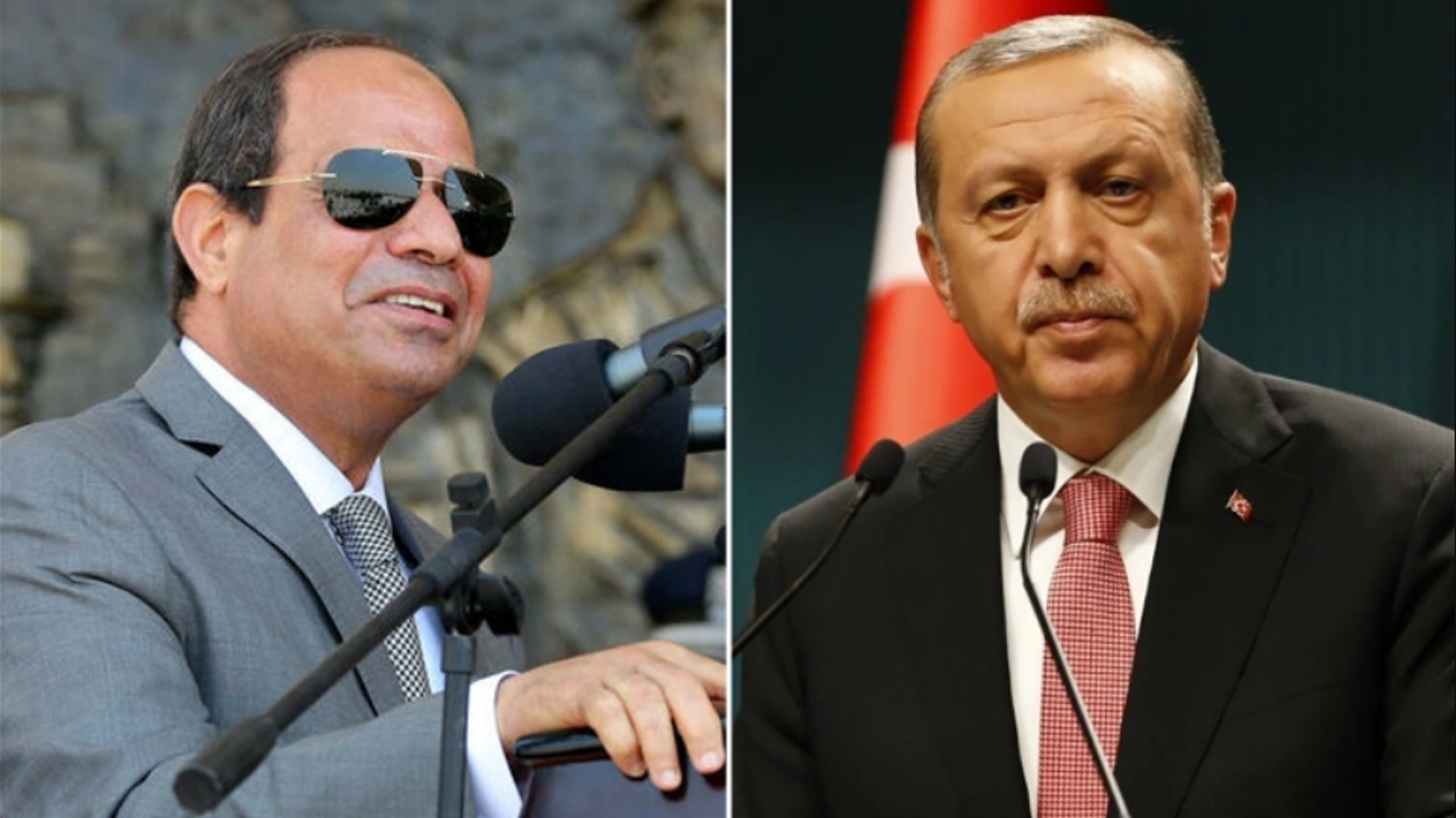

Two developments in recent months have highlighted the escalating tensions in Turkish-Egyptian relations. Egyptian President Abd al-Fattah al-Sisi vowed in July to send troops to Libya to halt the eastward advance by Turkish-backed Libyan forces under the Government of National Accord (GNA), calling Jufra and Sirte “a red line.” More recently, Greece and Egypt concluded an agreement demarcating an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the eastern Mediterranean, just as talks between Greece and Turkey over maritime border disputes were about to begin and at a time when Greek-Turkish relations are at a nadir.

Of course, tensions between Turkey and Egypt are not new. Ties between the two states have steadily deteriorated since the Egyptian military coup in 2013. Not only did Turkey stridently condemn the illegitimate removal of President Morsi, it welcomed Egyptian activists and former government officials opposed to the coup, turning Istanbul into a centre of Egyptian opposition activity. Turkish-Egyptian diplomatic relations were severed later that year, after which Egypt increasingly aligned itself with forces opposed to Turkey’ active political and economic role in the region. In January 2019, for example, Egypt invited Greece, Israel, Cyprus and Italy to establish the EastMed Gas Forum, pointedly excluding Turkey. Ankara’s late-2019 military and economic maritime agreement with the GNA further soured relations, giving Turkey a toehold on Egypt’s eastern border and enabling the GNA to rout General Haftar’s forces, which are backed by Egypt and the United Arab Emirates.

Nevertheless, despite the recent escalation and the stark divide between their vision of their interests and roles, both Turkey and Egypt realise that a direct clash would be damaging for both of them. In fact, there are indications that both states are more pragmatic than their bellicose statements indicate. Back-channel intelligence communications were initiated in the wake of the GNA-Turkish agreement, as Egypt sought to assess Ankara’s intentions and what the maritime agreement would mean for its own interests in the eastern Mediterranean. In addition, Turkey surely noticed that the Egyptian-Greek EEZ agreement supported some of Turkey’s own stances, by insisting, for example, that Greek zone begin at the coastline of its mainland, rather than the islands, and by avoiding two areas that are particularly sensitive to Turkey. By the same token, Ankara showed some consideration for Egyptian concerns when it halted the GNA offensive on Sirte.

Most importantly, Turkish and Libyan sources confirmed that the ceasefire announced on 21 August 2020 by the GNA and House of Representatives—which seems to exclude Haftar from any political role—grew in part out of a Turkish-Egyptian consensus. While the United States took the lead in brokering the deal, it would not have been possible without Egypt’s agreement to side-line Haftar or Turkey’s willingness to cede the military option and establish a demilitarised zone along the Jufra-Sirte front.

Does this herald a thaw in Egyptian-Turkish relations?

Since 2013, Egypt has charted a strategic path at odds with Turkey, both in terms of its support for democracy and its regional alliances. As the Arab world’s most populous country, Egypt sees itself as the most significant player in the region and the Arab order. But the Sisi regime owes its existence and survival to Emirati and Saudi support and Israeli influence in Washington. It would be difficult to for Egypt to extricate itself from this web of regional alliances. Moreover, as Egypt strives to stake out a regional role, the Sisi regime sees Turkey as its main rival.

Even if Erdogan is willing to restore high-level communications between the states, it will therefore be hard for the Sisi regime to take concrete steps toward a Turkish-Egyptian consensus. More likely is that Ankara and Cairo will conclude, on purely pragmatic grounds, that the current tenor of relations could be costly for both countries and it is better and safer to contain the crisis by reaching whatever understandings are possible on individual issues.

Developments in the recent past suggest this is the current trajectory, but there is no guarantee that such understandings will prevent a renewed crisis if they prove unsatisfactory to either party.

*This is a summary of a policy brief originally written in Arabic, available here: https://studies.aljazeera.net/ar/article/4766.