|

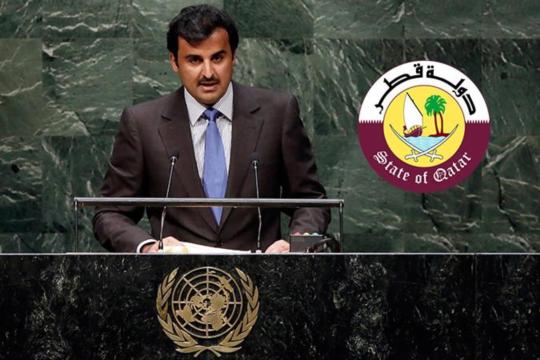

| Emir of Qatar, Sheikh Tamim Bin Hamad al-Thani, addresses the United Nations' 69th General Assembly in New York [AlJazeera] |

| Abstract Qatar’s foreign policy has undergone shifts in response to regional geopolitical developments. Though Qatari foreign policy was characterized by neutrality and mediation during the first decade of this millennium, it changed direction after the Arab Spring began, becoming more interventionist by outright support for Arab populations who were rebelling against authoritarian regimes and demanding greater freedom, dignity and the right to self-determination. With the ousting of former president Mohamed Morsi in Egypt, escalating tensions and conflicts in Libya, the expansion of the Islamic State (IS) in the region, Houthi control of major state departments in Yemen and the recent Israeli offensive on the Gaza Strip, the geopolitical landscape and regional power balances have again shifted. These events have impacted Qatari foreign policy as it responds to ongoing developments at the regional and international levels. By reactivating its mediation role (at which Doha excelled during the first decade of the millennium), utilising soft power tools and maintaining its commitments within international alliances to counter threats against Qatar’s national and regional security, Qatar’s foreign policy has entered a new phase of wielding “smart power” (as characterized by Jospeh Nye). |

Introduction

Since attaining independence in 1971, Qatari foreign policy has passed through various phases. There were two key turning points, the first being the transfer of power to Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani in 1995 and the second, his abdication of power to Crown Prince Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani in June 2013.

Like that of most other Gulf states, Qatar’s foreign policy was generally in agreement with the Saudi government’s foreign policy until the mid-1990’s, when Doha carved an independent foreign policy path after Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani came to power in June 1995.(1)

Adopting an “open” foreign policy, which relied on soft power tools such as media, diplomacy, education, culture, sports, tourism, economics and humanitarian aid, Doha’s strategy was based on being a friendly neighbour and the formation of strategic alliances with major and middle powers.(2)

Since the current ruler came to power, the Arab region has undergone several substantial changes that have reshaped the geopolitical landscape and regional power balances. The most significant of these are the ousting of former Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi, escalating tensions and conflicts in Libya, the geographical and ideological expansion of the Islamic State (IS) in the region and the Houthi group’s control of major state departments in Yemen. Each of these events, among others, has undoubtedly impacted Doha’s foreign policy and how it responds to developments in the regional and international arenas. This report illuminates the most prominent changes in Qatar’s foreign policy since Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani came to power on 25 June 2013.

Fixed principles of Qatar’s foreign policy

Qatar’s international relations doctrine focuses on the consolidation of peace and stability. Article 7 of the Qatari constitution states that the country's foreign policy is “based on the principle of consolidating international peace and security”.(3) It is based on the principles of encouraging settlement of international disputes by peaceful means, supporting peoples’ rights to self-determination, non-interference in the internal affairs of other states and cooperation with peace-loving nations.

Since the mid-1990s, successive Qatari governments have upheld these principles, especially during the first decade of this millennium. Before the outbreak of the Arab Spring, then-Emir Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani adopted diplomacy that focused on mediation and conflict resolution, which meant that Doha assumed the mediator role in almost every regional conflict, including Sudan, Eritrea, Lebanon, Palestine, Somalia and Yemen.

The positive results of this mediatory role secured recognition and credibility for Qatar at both the regional and international levels. Two examples are the May 2008 Lebanon agreement and the 2007 release of the Bulgarian nurses and Palestinian doctor detained in Libya. This determination to resolve disputes by peaceful means and to play the role of mediator are also accompanied by Doha’s willingness to accede to international arbitration over disagreements about Qatar's borders with its neighbours, as happened with Bahrain in the early millennium.

While these are the general principles guiding Qatar's foreign policy, during the past four years developments in both the regional and international arenas have shaped new principles that impacted the country's foreign affairs.

From neutrality to influence

For fifteen years, Qatar's foreign policy was distinguished by its neutrality and impartiality, until December 2010, when the outbreak of Arab Spring protests catalysed a historic shift in the political landscape of the region. Arab peoples which had been subjected to repression since their countries gained independence suddenly took to the streets to reclaim their freedom, dignity and right to self-determination.

The revolution that started in Tunisia was perceived as a threat by several dictatorships in the Arab world, while Qatar's national leadership responded by supporting Arab nations’ choices, again based on Article 7 of Qatar’s constitution, “supporting the right of self-determination of people”. Consequently, the country's international image changed, with Qatar regarded as an active supporter rather than a conciliating mediator.(4) Qatar participated in military action in April 2011 under the NATO-led international coalition against Colonel Muammar Gaddafi’s forces in Libya, and, as part of the Arab League, Qatar also called for Arab troops to be sent to Syria to stop the bloodshed there.

A regional power vacuum during 2011-2013 prompted a shift in Qatar’s foreign policy and pushed the country to assume a leadership position, especially within the Arab League. Traditional powers in the Arab world were suffering a decline for various reasons. Riyadh was focused on its internal affairs because nascent rebellious movements had emerged within its borders, particularly in its eastern regions. Cairo was struggling in the transitional period that followed the January 2011 Egyptian revolution. Iraq was still reeling from the 2003 American invasion, while Syria was grappling with the popular revolt that broke out in March 2011 and has continued since.

The Arab Spring revolutions and Qatar's consistent position, as well as the positions of international and regional powers, such as the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), provided an opportunity to begin a new phase in Qatari foreign policy, one aligned with the vision of Doha’s political leadership at the time.(5) There was a clear difference between Qatar's position on the Arab Spring revolutions and various GCC country positions at both the political and diplomatic levels. This is embodied in official statements, as well as in actions including humanitarian, logistical and financial support and economic investment.

Qatar’s regional strategic framework sought a balance between regional powers, and Doha was therefore placed in a very sensitive position vis-à-vis its support for the rising powers in countries undergoing socio-political change, some of which were proponents of political Islam. Doha had to be cautious not to provoke its northern neighbour Iran on the one hand, as well as certain Gulf states which classified the Muslim Brotherhood as a banned terrorist organisation on the other. Qatar’s policy of “impact and influence” seems to have been successful for them, thanks to the changing political climate and divided geopolitical structures across the region due to the Arab Spring revolutions. This substantial shift in Qatar's foreign policy appears to reflect its confidence both in independent decision-making and its ability to perform on par with other countries in the region.

The transition to smart power

When Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani came to power, Qatar's diplomacy style changed significantly, in line with various recent developments in the region, particularly in Egypt, Iraq and Syria. Qatar's foreign policy tools underwent significant development with respect to the conceptualisation of both soft power and smart power.

Just days after Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani assumed power, the Egyptian military overthrew the first elected civilian president in Egypt’s history on 3 July 2013. Some countries in the Arab region explicitly welcomed the coup, while most Western powers overlooked it. At the regional level, Turkey expressed its rejection of the sudden breakdown of Egypt’s democratic process. Qatar called for reconciliation between the various disputing groups in Egypt, but the new Egyptian leadership was betting on suppressing protesting voices and on the exclusion of the Muslim Brotherhood movement from the political scene as a whole. These developments forced Qatari leadership to adapt and reshape its policies in accordance with changing priorities.

Qatar's diplomatic moves were somewhat quiet when compared with its previous stance, which can be attributed to the new leader’s desire to strategically shape his country's foreign policy in line with Joseph Nye’s determinants of “smart power”,(6) combining both soft and hard power approaches, while maintaining the constitutional principles underpinning Qatar’s foreign policy. The relatively quiet diplomacy of Qatar may be regarded not as a retreat, but rather as a foreign policy shift to bolster soft diplomacy tools such as the media and to bolster the economy through increased investment at home and abroad. Further, it aims to enhance education through promoting intellectual advancement and international events in various fields of culture, arts and sports. Policymakers are aware that these issues will be at the centre of the country's foreign affairs in future years.

Qatar's decision-makers have adopted an open-door policy for dialogue with all parties wherever feasible, with an explicit emphasis on not excluding any group from the political scene. Because this stance contradicts that of some neighbouring countries who chose to confront some political Islam movements, it has fuelled disagreements within the Gulf Cooperation Council, and led to member states Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and the UAE withdrawing their ambassadors from Doha on 5 March 2014.(7) Undoubtedly, this constituted the biggest challenge that Sheikh Tamim faced during the first year of his reign. It was an unprecedented crisis in the history of relations between members of the GCC and highlighted deep disagreements between Gulf capitals regarding regional issues.

Redirecting Foreign Policy

Countries in the region have adopted different approaches towards the tide of political Islam that has gained popularity in a number of countries affected by the Arab Spring.(8) While the Muslim Brotherhood is a banned terrorist organisation in countries such as the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, Qatar considers this group as one of the formative forces on the political map of the Arab world and argues for communication with the group and its inclusion in the political arena, particularly since this organisation (the Muslim Brotherhood) is also a significant factor in the polity of a number of other Gulf Arab states, including Kuwait and Bahrain.

Developments in the region during the past three months, following the expansion of the Islamic State (IS) to the north in both Syria and Iraq, as well as Yemen's state departments falling to the Houthi group in the south, have led the Gulf countries to review their inter-relations. They sought to put an end to their disagreements in order to unite against security threats at both the national and regional levels. Hence, Riyadh’s mediation to resolve the Gulf crisis between Qatar on the one hand and the UAE, Bahrain and itself on the other, reflects Saudi decision-makers' awareness of the seriousness of the regional crisis and their responsibility as one of the central countries of the region.

Qatar has expressed flexibility and willingness to overcome the crisis with its neighbours in the GCC. The Emir’s speeches in Germany(9) and at the United Nations during September 2014(10), as well as in his television interview on American news channel CNN(11), are public indications of this stance and present a combination of the old and the new features of Qatar's foreign policy. In other words, this suggests that the country’s foreign policy has been adjusted without compromising the essence of the fundamental principles laid out in Qatar’s permanent constitution, with an emphasis on independent decision-making.

The principle of mediation, which was incorporated into Qatar's foreign policy during the first decade of the millennium, remains one of its most important features, with Doha seen as a model for solving regional and international conflicts. The Emir of Qatar, Sheikh Tamim Bin Hamad al-Thani, has made a call in recent international forums, to promote a culture of dialogue and “preventative diplomacy” through pre-emptive peaceful methods rather than pre-emptive war, as well as support for governments to implement gradual reforms. All signs suggest that Doha wishes to explore more flexible foreign policy approaches than those adopted after the outbreak of the Arab Spring revolutions in late 2010 without changing the fundamentals of Qatar's foreign policy, which are not open to compromise.

Conclusion

In recent years, the Arab Spring and its repercussions have catalysed the transition of Qatar's diplomacy from the diplomacy of mediation to the diplomacy of influence. There is no doubt that the independence of Qatar’s foreign policy is underlined by its autonomous income sources (derived from the production and export of oil and gas as well as external investments), which confers competitive advantages as a regional power.

Qatar’s emergence as a rising regional power since the start of the millennium has capitalised both on its significant economic base and on the leadership vacuum that once was occupied by major regional powers such as Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Iraq. An added factor was the United States’ reluctance to interfere in regional conflicts after disastrous experiences in both Afghanistan and Iraq.

Qatar's transformation into an influential regional and international power after the Arab Spring revolutions was a turning point in Doha’s foreign policy approach, taking advantage of the multi-dimensional soft power tools that had been developed and strengthened during the previous decade and beyond. This change demonstrated that Doha’s foreign policy is flexible and uses multiple strategic options based on the independence of its decision-making.

Accordingly, the recent readjustment of Qatar's foreign policy is consistent with developments affecting the region: in the interests of the state, it is necessary to redirect its external policies to serve its national interests without compromising its principles. This is evident from Qatar’s return to the mediator role and the use of soft power tools with a continued commitment to international alliances aimed at stopping any threat against its national security or the security of the region.

_____________________________________

* Dr Jamal Abdullah is a researcher at AlJazeera Centre for Studies specialising in Gulf affairs.

References

1) Jamal Abdullah, Qatar’s Foreign Policy 1995 – 2013: Leverages and Strategies. (Doha: AlJazeera Centre for Studies, 2014).

2) Jamal Abdullah, Qatar's position from the Arab Spring: “Qatar's foreign policy: from neutrality to influence”, in Gulf in the Context of a Strategic Shift, ed. Mohammed Badri Eid and Jamal Abdullah, (Doha: AlJazeera Centre for Studies, 2014).

3) State of Qatar, Permanent Constitution of the State of Qatar, Article 7, http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---ilo_aids/documents/legaldocument/wcms_125870.pdf.

4) Jamal Abdullah, “The Foreign Policy of the State of Qatar (1995-2014): Transformations and Horizons”, Al Diplomat, 10:2014.

5) Jamal Abdullah, Nabil al-Nasiri, “Qatari Foreign Policy: Carryover or Redirection?”, AlJazeera Centre for Studies, 2 July 2014, http://studies.aljazeera.net/sites/default/files/migration/ResourceGallery/media/Documents/2014/7/10/2014710114831205734Qatari%20Foreign%20Policy%20Carryover%20or%20Redirection.pdf.

6) Yahya Yahyaoui, “Obama and the Thesis of Smart Power” (Arabic), 18 November 2013, http://www.aljazeera.net/knowledgegate/opinions/2013/11/18/%d8%a3%d9%88%d8%a8%d8%a7%d9%85%d8%a7-%d9%88%d8%a3%d8%b7%d8%b1%d9%88%d8%ad%d8%a9-%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%82%d9%88%d8%a9-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b0%d9%83%d9%8a%d8%a9.

7) Jamal Abdullah, “Motives and Consequences of Ambassador Withdrawals from Doha”, AlJazeera Centre for Studies, 24 March 2014, http://studies.aljazeera.net/en/reports/2014/04/201441061248251708.htm.

8) Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, Qatar and the Arab Spring: Policy Drivers and Regional Implications, 24 September 2014, http://carnegieendowment.org/2014/09/24/qatar-and-arab-spring-policy-drivers-and-regional-implications.

9) Sheikh Tamim Bin Hamad al-Thani, Public Speech, Germany, 17 September 2014 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k6eYQJQYsxM.

10) Sheikh Tamim Bin Hamad Al Thani, Public Speech, UN General Assembly, 24 September 2014 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3bZRLLLwMsc.

11) Sheikh Tamim Bin Hamad Al Thani, CNN Interview with Christiane Amanpour, 25 September 2014, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vR9ezioJ4kQ.