|

| [AlJazeera] |

|

Abstract Japan's policy on the Gulf region depends to a large extent on two basic principles, namely, economic interests and reliance on the United States with regard to securing shipping lanes. As a result of the scarcity of energy resources in Japan, the country relies excessively on energy supplies from the Gulf region which is rich with such resources. However there are several issues that could affect the relations between the GCC countries and Japan. The increasing likelihood of economic sanctions on Iran being lifted will no doubt ignite competition in the Japanese market. Despite the fact that Tehran may not be able to export liquefied natural gas (LNG) as it needs to develop this sector, a process that will require huge investments and may take several years until realised. However, it is likely that the Iranian energy products will make a strong entry into market competition, where Japanese companies look to invest in Iran's energy sector after the expected lifting of the economic sanctions on Tehran in the next few months. This means that Tokyo will seek to diversify its imports of needed energy products. Although Japan has drawn up an ambitious policy to diversify its energy sources and imports, it will continue to import large amounts of oil and LNG over the next two decades. Since these goods are vital for global economic growth, Japan cannot ignore repercussions of developments in the Middle East region. In particular, the Fukushima disaster and its aftermath affirmed the importance of the Gulf region to Japanese decision makers. Japan has also pioneering experience in the field of energy efficiency, which all countries in the region can benefit from. In addition, the new developing energy trends in the GCC countries include more energy efficiency in buildings, district cooling, and smart grids. These trends increasingly affect the direction of their energy policy. It is likely that the Gulf countries will allocate billions of dollars for renewable energy projects in the coming years, and this in turn would open the way for Japanese companies to invest and develop relations in the new sectors in the region. |

Introduction

Japan is considered the world’s third largest economy and is also the third largest ‘industrial’ economy after China and the United States. Yet, the country lacks natural resources necessary to sustain its technological and industrial development. Japan at present is the largest LNG importer, the second largest importer of coal and the third largest importer of crude oil and oil products in the world.

In contrast, the GCC economies largely depend on energy exports in financing their economic development. In this context, GCC-Japan trade relations have grown substantially and later developed into the participation of Japanese companies in the development of infrastructure in GCC countries. However, trade is at the heart of the growing links between GCC countries and Japan, which centre on the crude oil and gas.

Japan’s Gulf policy is largely based on two principles, firstly, its economic interests, which depend on securing oil supplies, and secondly, reliance on the United States with regard to securing shipping lanes from the Strait of Hormuz to their final destination in Japanese ports via the Strait of Malacca. As a result of the scarcity of energy resources in Japan – since the establishment of diplomatic ties with the first Gulf state, Saudi Arabia, sixty years ago (1955) – the country excessively depends on energy supplies from the Gulf region.

Dependence on gas and oil supplies from the Middle East region has driven Tokyo to maintain close relationships with the Gulf countries. Thus, economic relations between the GCC countries and Japan developed, with Japan becoming the GCC’s foremost trading partner for a long period of time. Yet, the economic recession that hit Japan in the 1990s combined with China’s economic boom, and the growing importance of India’s economy influenced trends in the foreign trade of the GCC countries. Despite Japan's the economic importance, emerging economies such as China, India and even South Korea have began to compete in all areas.

Economic relations: energy, the heartbeat of trade

It is difficult to talk about GCC–Japan economic relations without addressing energy issues which are at the heart of relations between the two countries. Two major factors characterise trade relations between the two sides: firstly, the volume of energy exports from the Gulf region, and secondly, global oil prices. Therefore, the fluctuating value of trade exchange between the two sides over several years can be linked to the two factors mentioned above.

Table 1 highlights this clearly, showing that the value of Japanese imports from GCC countries jumped by forty per cent in just one year as a result of the rise in oil prices, while Japan’s exports relatively maintained their value. In contrast, with a drop in oil prices, the value of two-way trade between the two sides decreased by four per cent in 2014, reaching 161.8 billion US dollars (USD) (approximately eleven per cent of Japan’s total foreign trade volume).(1)

This trend is expected to continue during the current year, with the value of two-way trade between Japan and the GCC plunged almost 42 per cent to 50.4 billion USD during the first half of 2015, compared with 86.5 billion USD during the same period in 2014.(2) This situation is unlikely to change in the near future, therefore, oil and gas supplies will continue to represent the backbone of the Japan–GCC relations.

Table 1: Japan’s trade with GCC countries

|

Growth rate % 2014 |

2014 |

2013 |

2012 |

2011 |

2010 |

|

|

11.18 |

24.9 |

22.4 |

24.9 |

19.6 |

20.1 |

Japanese exports to Gulf countries (billion USD) |

|

-5.45 |

139.8 |

148.9 |

157.2 |

142.6 |

102.3 |

Japanese imports from Gulf countries (billion USD) |

|

-3.82 |

164.8 |

171.3 |

182.1 |

162.2 |

122.4 |

Total trade (billion USD) |

|

-9.14 |

114.90 |

-126.47 |

132.23 |

-123 |

82.2 |

Trade balance deficit (billion USD) |

Source: Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO)

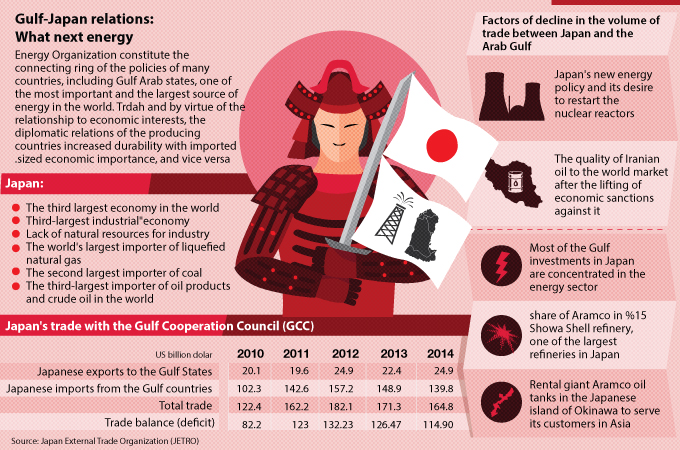

Energy imports constituted nearly 98.5 per cent of Japan's total imports from the GCC countries in 2014. (3) Despite a decline in Japan's imports of crude oil from the Gulf countries by about five per cent or approximately 2.65 million barrels per day (bpd) in 2014, compared to 2.79 million bpd in 2013, they accounted for more than three-quarters of Japan's total imports of crude oil in 2014, which amounted to about 3.44 million barrels. On the other hand, Japan imported about 34.06 million tonnes of petroleum gas (including liquefied natural gas, liquefied propane and butane) from the GCC countries. The State of Qatar was the world's second-largest supplier of LNG to Japan after Australia, providing it with about eighteen per cent of its total needs in 2014, while the United Arab Emirates (UAE) came in sixth place with six per cent, and the Sultanate of Oman in ninth place with four per cent (see Table 2, Figure 1).

Table 2: Japan’s major imports from GCC countries (billion USD)

|

Growth Rate % 2014 |

Total % |

2014 |

2013 |

2012 |

|

|

-8.96 |

72.61 |

101.53 |

11.521 |

115.80 |

Crude |

|

-2.88 |

20.60 |

28.81 |

29.66 |

31.96 |

Gas (liquefied gas, propane & butane) |

|

21.90 |

5.25 |

7.35 |

6.03 |

7.62 |

Light oil (condensates and others) |

|

44.77 |

0.78 |

1.09 |

0.756 |

0.667 |

Aluminum |

|

10.59 |

0.39 |

0.545 |

0.492 |

0.450 |

Organic chemicals |

|

32.99 |

0.12 |

0.163 |

0.122 |

0.139 |

Copper (majority is scrap) |

|

4.96 |

0.11 |

0.149 |

0.142 |

0.150 |

Plastics |

|

-19.96 |

0.01 |

0.017 |

0.021 |

0.025 |

Precious stones |

|

-6.08 |

100.00 |

139.83 |

148.89 |

157.18 |

Total |

Source: Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO)

Therefore, it is not surprising to note that most of the Gulf investments in Japan are concentrated in the energy sector, and perhaps the most important is the share of approximately fifteen per cent owned by Saudi Aramco in Showa Shell refinery, one of the largest refineries in Japan. (4) In addition, Aramco leases giant crude oil storage tanks on the island of Okinawa in southern Japan, which have a capacity of 6.4 million barrels, geared to serve its customers in Asia, and even the west coast of the United States of America.(5)

Figure 1: Japan’s major crude oil and gas suppliers

However, looking beyond energy the significance of the trading relationship starts to fade.. Other GCC exports to Japan range from precious stones to plastic and aluminium, but all pale in comparison to the oil and gas sales.. In contrast, motor vehicles, machines and transport equipment make up the largest category of products and commodities the GCC countries import from Japan, representing almost three-quarters of the total Gulf imports from the country (see Table 3). While it is true that Japanese companies are also present in various sectors in the Gulf countries, especially energy, they have been facing fierce competition from US, European and even Asian companies, South Korean in particular.

Table 3: Japan’s major exports to GCC countries (billion USD)

|

|

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

Total % |

Growth rate % 2014 |

|

Motor vehicles |

14.66 |

13.60 |

14.79 |

59.34 |

8.77 |

|

General Machinery |

3.89 |

2.78 |

3.45 |

13.83 |

24.06 |

|

Iron/steel (products) |

1.44 |

1.99 |

1.58 |

6.36 |

32.15 |

|

Electric machines |

1.18 |

0.971 |

1.20 |

4.82 |

23.71 |

|

Rubber (tyres and others) |

1.18 |

1.07 |

1.01 |

4.05 |

5.53- |

|

Iron/steel (structural) |

0.919 |

0.705 |

0.555 |

2.23 |

21.16- |

|

Textiles |

0.351 |

0.333 |

0.295 |

1.19 |

11.35- |

|

Visual goods |

0.248 |

0.247 |

0.258 |

1.15 |

15.16 |

|

Foodstuffs |

0.064 |

0.71 |

0.083 |

0.33 |

16.83 |

|

Total |

24.95 |

22.42 |

24.93 |

100.00 |

11.18 |

Perhaps most importantly is that over the past decade, there have been some significant changes in GCC trade patterns. Although Japan is still the major export destination for the Gulf countries (see Table 4), its share fell from over twenty-three per cent in 2000 to about fifteen per cent in 2014. Japan also slipped as the largest GCC trading partner to third place after the European Union and China. That place is also expected to be overtaken by other countries such as India and perhaps South Korea before the end of this decade. These changing trade patterns reflect the shifts in global economic power toward emerging markets, especially with regard to China and India, which are expected to become the GCC’s most important trading partners by 2020.(6)

Table 4: Gulf major export and import markets

|

Gulf major export markets |

|||||

|

|

2000 |

|

|

2014 |

|

|

|

Billion USD |

Total % |

|

Billion USD |

Total % |

|

Japan |

38.3 |

23.3 |

Japan |

139.7 |

15.7 |

|

South Korea |

19.2 |

11.7 |

South Korea |

100.7 |

11.3 |

|

USA |

17.4 |

10.6 |

China |

98.3 |

11.1 |

|

Singapore |

7.9 |

4.8 |

India |

93.6 |

10.5 |

|

China |

5.9 |

3.6 |

EU |

64.4 |

7.2 |

|

Holland |

4.3 |

2.6 |

USA |

51.0 |

5.7 |

|

Gulf major import markets |

|||||

|

|

2000 |

|

|

2014 |

|

|

|

Billion USD |

Total % |

|

Billion USD |

Total % |

|

USA |

9.8 |

13 |

EU |

113.8 |

22.7 |

|

Japan |

7.6 |

10.1 |

China |

68.6 |

13.7 |

|

UK |

5.3 |

7.1 |

USA |

52.7 |

10.5 |

|

Germany |

5.3 |

7.0 |

India |

51.3 |

10.2 |

|

France |

5.9 |

5.2 |

Japan |

24.9 |

4.9 |

|

China |

4.3 |

5.1 |

South Korea |

19.8 |

3.9 |

Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF)

Indicators that may reduce trade between Japan and the Arab Gulf states

In the absence of a real base to diversify the production structure of GCC economies, it is expected that the GCC export structure will remain unchanged for the next decade at least. Of course internal developments in Japan may carry with them unpleasant news for energy exports from the Gulf Arab states.

Japan’s new energy policy

Before the Fukushima disaster in March 2011, nuclear power accounted for about one-third of total electric power generation in Japan. Since the disasters, Tokyo has relied on the import of fossil fuels (coal, LNG and oil), representing around ninety per cent of its energy needs.(7) However, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has said on more than one occasion that his government is seeking to restart nuclear reactors in order to reduce the country's dependence on costly energy imports. Here it should be noted that the bill of Japan's imports of fossil fuels during the three years following the Fukushima disaster reached about 270 billion USD, or fifty-eight per cent higher than it was previously,(8) this contributed to the growth of the trade deficit significantly. There is no doubt that the situation has changed this year as a result of the decline in oil prices; regardless, energy imports remain more expensive than nuclear energy.

In this context, in July 2015, the Japanese Ministry of Industry approved a new plan, which aims to raise the contribution of nuclear energy to about twenty-two per cent of total electricity generation in Japan by 2030, while it is expected that clean energy sources will account for up to twenty-four per cent. Although the number of nuclear reactors that could run again in Japan is still unknown, it remains likely that five to seven reactors will be brought back into operation by 2017, which means that 11.5 gigawatts of electricity will be added to the entire network in Japan.(9) This in turn could reduce imports of LNG by about eleven million tonnes, or the equivalent of twelve per cent of the country's imports of LNG during 2014.(10)

In the medium and long terms, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), the restart process will be slow and cautious during the remainder of 2015, while it is expected that a total of fifteen nuclear reactors will be operating by 2020.(11) BMI Research expects about twenty nuclear reactors to be operating by the year 2024, which represents about ten per cent of the total power generation.(12)

As part of these plans, Japan is seeking to reduce LNG imports to about sixty-two million tonnes by 2030.(13) According to data from the Japanese ministry of finance, Japan is the largest energy consumer in the world, having imported about eighty-nine million tonnes of LNG (121.04 billion cubic meters) in the year that ended on 31 March 2015.(14) In the aftermath of the Fukushima disaster, Japan has increased its imports of LNG by eighteen million tonnes per year, with imports of seventy million tonnes in 2010 rising to about eighty-nine million tonnes in 2014, an increase of twenty-six per cent. Since 2011 Japan has bought most of the LNG from spot markets or through short-term contracts. These quantities may disappear if Japan goes ahead with its energy plans.(15)

Certainly, this is bad news for Doha. It is true that most LNG exports are concluded in the framework of long-term deals, but Qatar still exports about one-third of its production through the spot market and short-term contracts. More importantly, Japan is seeking to diversify its sources of LNG imports from countries such as Australia, Papua New Guinea, the United States and Russia. All of these factors will cast a shadow on Japan's imports from the Middle East and are likely to reduce demand for Qatari gas as well as strengthen the negotiating position of Japanese companies in any future negotiations for the conclusion of new contracts or the renewal of existing contracts as several of them due to expire at the beginning of the next decade.(16)

Perhaps the picture in the context of oil imports is not much different from that of gas. Oil consumption in Japan has dropped by about twenty-two per cent since 2000. This decline is due to many structural factors, such as: fuel replacement, population decline and goals of energy efficiency imposed by the Japanese government.(17) It is very likely that such a trend will strengthen in the future, especially with the re-start of nuclear power in Japan, the high contribution of renewable energy sources and an increase in energy efficiency in the automotive sector. This situation is bound to reduce demand for crude oil.

According to some estimates, Japan's oil imports are expected to drop to about three million barrels per day by the year 2024.(18) Therefore, demand for GCC oil may decrease or it is likely to face fierce competition of oil imports coming from Iran and other countries, such as Russia, Kazakhstan and Iraq, as well as African countries and even the USA.

Figure 2: Oil consumption drops in Japan and rises in China and India

The return of Iranian oil

The increasing likelihood of lifting economic sanctions on Iran will ignite competition in the Japanese market. It is true that Tehran cannot export LNG, because it needs to develop this sector from scratch, a process that requires huge investment and several years for the construction of the necessary infrastructure. Nevertheless, Iranian oil may enter the competition strongly, and here it should be noted that Japanese imports from Iran exceeded 166 thousand bpd in 2014, or the equivalent of five per cent of the total oil imports, down from 314 thousand barrels or about nine per cent in 2011 before international sanctions on Iran were tightened.(19) Japanese companies will look to invest in Iran’s energy sector after the international community lifts the economic sanctions imposed on Tehran in the next few months.(20)

In the long term, Japanese companies are waiting for Iran’s return to the global gas market and entry into competition with other exporters. Thus, they aspire to get contracts under which in the future they will seek to import oil and gas at a lower price than they currently pay to a number of GCC countries. However, Japanese decision makers will take into account relations with the GCC States, Iran's investment environment, and Iran's regional policies and their impact on neighbouring countries, which are important factors that will play a decisive role in the decision to enter the Iranian energy market and in determining this entry’s size.

Here it should be noted that Japan supports US foreign policy in the region, it is a strong ally of America and hosts tens of thousands of US troops on its territory. Japan believes that the signing of the nuclear agreement between Iran, on the one hand, and the P5+1, on the other hand, is positive development and in the international community’s interest. Japan also believes that the United States will work to reassure its allies in the Gulf (the GCC countries) that the agreement is in the interest of all parties and will not have negative repercussions on the region’s security.

Conclusion

Although Japan has drawn up an ambitious policy to diversify energy sources and imports, it will continue to import considerable amounts of oil and LNG over the next two decades. Since these commodities are still considered vital for global economic growth, Japan cannot ignore the repercussions of developments in the Middle East. The Fukushima disaster experience showed the importance of the Gulf region in particular for Japanese decision makers.

Perhaps Kintaro Sonoura, Japan's Vice-Minister for Foreign Affairs, expressed this sentiment unequivocally: ‘The Japanese government and people feel grateful to the GCC countries in general and Qatar in particular for standing with Japan, which sustained immense damage as a result of the earthquake and natural disasters that befell the country in 2011. The State of Qatar sent free shipments of LNG to Japan and established a Qatari–Japanese friendship fund for humanitarian assistance to those affected by these natural disasters in Japan.’(21)

As previously mentioned, Japan has a well established background with regards to energy conversion, of which all countries in the region can take advantage of. Future energy policy direction will be increasingly affected by emerging energy trends currently developing in GCC countries; energy efficiency in buildings, district cooling to name a few. GCC funded renewable energy projects may allow Japanese companies to diversify and establish new alliances within this sector.

Within this context, the Japanese deputy foreign minister added ‘the success of the rationalisation experience in Japan came, before anything else, as a result of education, and the spreading of awareness and knowledge to which the Japanese government has attached great importance in order to deliver it to the new generation.’

The Japanese private sector is also looking to invest in new sectors, such as urban transport, energy efficiency, desalination of seawater, environmental conservation and health care, as well as sectors such as nuclear energy, solar energy and infrastructure. Moreover, Japan has the skills and technical expertise for the exploration and extraction of unconventional oil and gas resources, or shale, effectively and at a reasonable cost. Saudi Arabia has considerable reserves of shale gas and can cooperate with Japan in this area. Japan is also a leading country worldwide in the field of methane hydrate exploration. Its technology can be marketed globally, especially in Gulf region (with the exception of Qatar), which urgently need natural gas for power generation and feeding its industries, especially petrochemicals.(22)

Future trends will see a need to move beyond energy sources such as oil and gas and a heavy focus on renewable energy which could be widely used. Japan and the Gulf countries may work together to provide research into developing a more sustainable energy which will have a large impact on the global market not to mention future generations and the environment

_________________________________________.

Copyright © 2015 Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, All rights reserved.

*Dr. Jamal Abdullah: Gulf Affairs Researcher, and Dr. Nasser al-Tamimi: Academic & Energy Researcher.

References

1. Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) (2015). ‘Japanese Trade and Investment Statistics’, (accessed 1-3 October 2015), < https://www.jetro.go.jp/en/reports/statistics.html >.

2. Ministry of Finance, Japan (2015) ‘Trade Statistics of Japan’, (accessed 5 October 2015), < http://www.customs.go.jp/toukei/info/index_e.htm >.

4. ARAMCO (2014). ‘Annual Review 2014’, 11 May 2015, (accessed 1 October 2015), < http://www.saudiaramco.com/en/home/news-media/publications/corporate-reports/annual-review-2014.html >.

6. Dudley D (2014). ‘Tokyo Drifts From GCC's Trade Sphere’, Bloomberg Business Week, 13 October 2014, (accessed 1 October 2015), < http://www.businessweekme.com/Bloomberg/newsmid/190/newsid/251/Tokyo%ADDrifts%ADFrom%ADGCCs%ADTrade%ADSphere1/4 >.

7. Martin, A (2015). ‘Japan Restarts Nuclear Power After Two-Year Shutdown’, The Wall Street Journal, 11 August 2015, (accessed 29 September 2015), < http://www.wsj.com/articles/japan-restarts-first-reactor-since-fukushima-disaster-1439259270 >.

8. Ibid; EIA ‘International energy data and analysis, Japan’, 30 January 2015, (accessed 28 September 2015), < http://www.eia.gov/beta/international/analysis.cfm?iso=JPN >.

9. Smith, M (2015). ‘Commentary: 10 challenges faced by the global LNG market’, Fuel Fix, 27 August 2015, (accessed 1 October 2015), < http://fuelfix.com/blog/2015/08/27/10-challenges-faced-by-the-global-lng-market/ >.

11. EIU (2015). ‘Reactor restart begins slow normalisation of energy policy’, 11 August 2015, (accessed 3 October 2015), < http://country.eiu.com/Japan/ArticleList/Updates >.

12. BMI Research (2015). ‘Japan Oil & Gas Report – Q3 2015’, London: Business Monitor International Ltd., 1 July 2015, p. 25.

13. Shimbun, Y (2015). ‘Japan flexes muscle over LNG prices: Imports down due to nuclear restart, green energy use’, The Japan News, 24 September 2015, (accessed 28 September 2015), < http://the-japan-news.com/news/article/0002446300 >.

14. Stapczynski, S (2015). ‘Japan's Nuclear Restarts Seen as Long-Term Drag on LNG Prices’, Bloomberg, 14 August 2015, (accessed 1 October 2015), < http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-08-14/japan-s-nuclear-restarts-seen-as-long-term-drag-on-lng-prices >.

15. MEES (2015). ‘LNG Demand Outlook Looks Bearish As Japan Restarts Nuclear Plant’, 14 August 2015, vol. 58, no. 33.

17. Ibid; EIA ‘International energy data and analysis, Japan’, 30 January 2015, (accessed 28 September 2015), < http://www.eia.gov/beta/international/analysis.cfm?iso=JPN >.

18. BMI Research (2015). ‘Japan Oil & Gas Report – Q4 2015’, London: Business Monitor International Ltd., 1 October 2015, p. 7.

19. EIA ‘International energy data and analysis, Japan’, 30 January 2015, (accessed 28 September 2015), < http://www.eia.gov/beta/international/analysis.cfm?iso=JPN >.

20. Extract from a meeting between researcher Jamal Abdullah and fellow colleagues in Japan’s Energy Economics Institute, 14–18/9/2015.

21. Extract from an interview researcher Jamal Abdullah had with Japan’s assistant foreign minister during a visit to Tokyo, 14–18/9/2015.

22. BMI Research (2015). ‘Japan Oil & Gas Report – Q4 2015’, p. 9.