Since the United States announced its decision to withdraw from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), commonly referred to as the nuclear agreement with Iran May 8, 2018, it has been clear President Donald Trump was determined to proceed with the two-phase plan to re-impose full sanctions on Iran. This shift would reintroduce the Iranian-American relations to a state of tension and hostility, ending the cautious optimism that the Nuclear Agreement could turn a new page on relations between the two countries, which have been in a state of crisis since the Islamic revolution overthrew the Shah in the late 1970s.

The first round of the sanctions, announced in August 2018, targeted non-petroleum economic sectors and the currency market in Iran. They had both direct and indirect impacts on several sectors:

- The purchase of American dollars, which resulted in a financial crisis with adverse consequences for the Iranian riyal.

- The trade in gold, silver, and precious metals.

- The import of minerals like graphite, coal, aluminum, and steel.

- Major deals in Iranian riyals.

- Transactions involving Iranian sovereign bonds.

The second round of sanctions, described as paralyzing, came on November 5. These directly targeted:

- The purchase of Iranian oil and petroleum products.

- Iranian ports, shipping, and naval industries.

- The Iranian energy sector.

- The provision of insurance services to Iran.

Washington said the sanctions were aimed at wholly preventing the export of Iranian oil, which was met with a threat from Iran to close the Hormuz Straits. But, the United States exempted eight countries (not including EU member states) from the ban on the import of Iranian oil, including Turkey, which declared its rejections of the sanctions. This move suggests that Trump left some room to maneuver to avoid an angry reaction to the sanctions. In any case, the sanctions are not consistent with the internationally accepted framework for such actions, since they are essentially punishing Iran even though it complied with the terms of the nuclear deal.

The effect of the sanctions is not limited to the economic sphere. This paper will discuss their impact on Iran’s foreign and domestic policy.

Oil and more

Commenting on the US decision, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani said, “We will proudly break the unjust sanctions.” Referring to the eight states that import Iranian oil and would be exempted from the sanctions regime, he said, “Even if the eight countries were not exempted, we would continue to sell our oil.” But, US sanctions did not end with oil, making them particularly onerous. They will touch several sectors. Most significantly, they threaten any transactions involving Iranian oil, whether with the Iranian National Oil Company or other Iranian companies, and this includes the purchase of oil, petroleum products, and petrochemicals. They also affect Iranian ports, shipping, and the shipbuilding industry, including the Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines, South Shipping Line, and their subsidiaries. Moreover, the US will sanction any foreign institutions that deal with the Iranian Central Bank or Iranian financial institutions, and this extends to financial transfer services. The sanctions also affect insurance and reinsurance services, and the Iranian energy sector.

According to US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, the new set of sanctions covers 50 Iranian banks and their branches. In the shipping and energy sectors, the sanctions affect more than 200 people and ships, along with Iran Air and 67 of its planes. In total, more than 700 Iranian natural persons, agencies, planes, and ships are listed on the American sanction list. Twenty countries have stopped buying Iranian oil in response to US pressure, and more are expected to follow given the threats issued by US Treasury Secretary Steve Manchin.

The US administration has threatened sanctions on the SWIFT financial transfer network if it provides its services to Iranian financial institutions covered by the US sanctions. The impact of such a step is clear when one recalls the difficulties faced by the Rouhani government—even after the sanctions were initially lifted—in resolving problems between the Iranian banking system and banks in other countries, which hindered bank transfers.

Oil prices dropped as sanctions were eased on Iranian oil exports, allowing major buyers to continue importing Iranian oil, even if only temporarily according to US statements. Iran is one of the world’s biggest energy players, holding 27 percent of global reserves of oil and gas (9 percent of oil reserves and 18 percent of gas reserves). Iran has proven reserves of 155 billion barrels of oil and was able to boost oil production to 3.8 million barrels per day. According to OPEC, Iran’s oil exports recently reached 2.1 million barrels a day. These exports bring in substantial revenue—$52 billion last year—accounting for nearly half of Iran’s total export revenues. Some 60 percent of the nation’s economy is relies on energy sector revenues.

Asian countries take 70 percent of Iran’s oil exports, followed by the EU with 20 percent. China is the number one importer of Iranian oil, buying 26 percent of the country’s oil exports last year, followed by India with 23 percent.

However capable Iran is of dealing with the sanctions, they are likely to affect its economy. In particular, they will impact its plan to increase oil production to 4.5 million barrels per day, which requires massive investments of up to $200 billion as well as foreign expertise, financing, and technology.(1)

Since Iran’s economy is still very dependent on oil revenues, the most significant effect of the US sanctions will be seen in the decline in oil revenues and petroleum exports.

Equally significant is the currency crisis resulting from restrictions placed on banks around the world and the higher transactions costs, which increases investment risk and stokes concern about the future of Iran’s economy and the potential for severe crises. These restrictions greatly hinder the normal course of foreign trade. It is these areas where the sanctions may be most keenly felt in the economy.

|

|

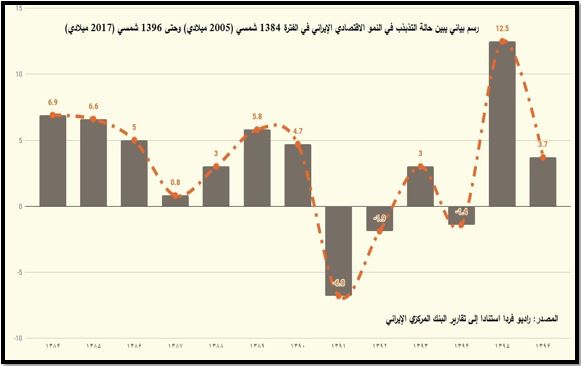

Title: Fluctuations in Iranian economic growth, 2005–2017 Source: Radio Farda, based on reports from the Iranian Central Bank |

Although Iranian economist Ali Sirr Zaim does not underestimate the impact of the sanctions, he believes that they will be no more than the US has imposed in the past. He is certain that Iran can deal with the crisis and maintain oil exports in spite of American threats. He also stated that several measures have been taken to regulate the Iranian economy in order to meet the challenges of this phase. Economists say that Iran will be better able to cope with the sanctions thanks to the lack of foreign debt and the strength and cohesion of the domestic front. (2)

Iranian economic problems are not solely the work of US sanctions; mismanagement also plays a role. According to economist Amir Reza Hassani, citing a report of the Shura Council’s research center, only 35 percent of economic problems experienced by Iran in recent years are the result of international sanctions. Some 65 percent were caused by domestic issues and mismanagement. (3)

Protest and Regime Change

Do the US sanctions seek regime change in Iran? The Trump administration has not made this explicit, but the US’s Iran strategy suggests it. The sanctions appear to be the instrument that the US will use to push the Iranian economy to the brink of collapse, in the hope that it will fuel protests, particularly those focused on the cost of living. The most recent protest began in Mashhad before moving to several other cities. Could the protests achieve Washington’s goals?

Discussions at the AJCS conference, “Iran in 2019,” attempted to answer this question. While participants affirmed the predicament facing the Iranian economy, they deemed it unlikely that the sanctions would spur an economic collapse, even given the slow economic development in the years following the nuclear deal. It is still more likely that Iranian society will persevere and the state will again focus its economy on neighboring states, much as it did to absorb the shocks following the 1979 revolution. Conference participants found no underlying cause for the collapse of the Iranian economy, which is based on a network of alliances—economic, social, and political—that carry through all government bodies, where both the opposition and loyalists are represented. In short, it does not appear that outside pressure will lead to change in Iran, and the conference participants were in agreement on the difficulty of regime change in Iran.

As for the protests, these are nothing new for Iran. Indeed, there have been a series of protest movements in the country since 1979, most significantly the protests of 1996, 2009, and 2017. Some researchers who presented papers at the AJCS conference argued that strikes due to inflation, a declining economy, and low wages are endemic to Iranian society; such political movements have a history that predates the revolution. Although conference participants from Iran affirmed the significance of the protests, they indicated that a “culture of protest” has evolved in Iran; as part of this, the state recognizes legitimate popular demands and has developed peaceful tools to deal with such actions.

Despite the foregoing, the impact of the sanctions on Iranian society cannot be denied. Azam Rajabi wrote his MA thesis at Tehran University, titled “The Impact of Sanctions on Social Welfare,”(4) to examine just this topic, gathering data through a survey of heads of households in Tehran. The findings of the survey showed that people’s living standards had been adversely affected by the sanctions: their purchasing power and income declined, and they had problems accessing certain goods. Health and medical conditions also deteriorated compared to the pre-sanctions period.

The survey found that the sanctions also had a psychological impact. People had a sense of relative deprivation, were less happy and satisfied with life, and more anxious about the future, job security, and their financial situation.

As demonstrated by the study, the sanctions had a marked influence on the Iranian people’s social well being, both material and psychological. If the goal of sanctions was to pressure the populace, they achieved their objective.

Iran in the Region

“Changing Iran’s behavior” is one way of stating the goal of US sanctions. While Washington sees Iranian policy as a factor for instability in the Middle East and is looking for ways to compel Tehran to change its behavior, Tehran sees its economic activity as necessary to its national security and a plus for regional security, and it sees the Middle East as the best arena for confronting American pressure.

Researcher Hassan Ahmadian, in a paper published by the AJCS,(5) points to domestic criticisms of this view: slogans decrying Tehran’s regional policy have been heard at several demonstrations, most recently in July 2018. Ahmadian states that while the demonstrators reject Tehran’s regional investments, the other side counters that these investments are not very big when measured by Iran’s enemies, and defending Iran’s national security is more important than financial accounts.

The same debate is taking place on the elite level. Some believe that regional policy costs could be limited by scaling back commitments and undertaking regional cooperation with Washington. The other camp—the one making the decisions—believes that the costs and the regional commitments are necessary to deter threats to Iran’s national security. This faction points to the nuclear agreement to prove the futility of negotiations in hopes of coming to an agreement with Washington on the region.

The US-based Peterson Institute for International Economics has prepared a sizable database on sanctions since 1990, collecting documentation on 200 instances of sanctions since World War I. They concluded that in about one-third of cases, the sanctions did spur changes in the other party’s behavior. The findings of the research were published in a book, Economic Sanctions Reconsidered. The institute concluded that sanctions had a much stronger impact on democratic countries than on non-democratic ones. In democracies, there are numerous channels by which the public can express its fears and in turn pressure its government to change its conduct.

Conclusions

• Reviewing numerous cases in the long history of sanctions, in most cases sanctions functioned as collective punishment for the populace without provoking regime change or encouraging the regime to change its behavior. The historical record demonstrates that in many cases international sanctions led to deteriorating standards of living and cost thousands of lives. In Iraq, for example, sanctions killed a half million children, a price that was “worth it,” according to Madeline Albright. In Cuba, the US unilaterally imposed economic sanctions in 1960 and increased them with time. These harmed people’s lives without weakening the regime. Sanctions against North Korea had led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people from hunger, and sanctions on Venezuela destroyed the country’s economy.

• In the case of Iran, decades of sanctions did lead to declining living standards for the public but were no hindrance to Iran’s growing regional influence. The reinstatement of these sanctions is not expected to achieve the goals announced by the US president. On the contrary, increased pressure on Iran will push it to redouble its regional presence, seeing this as a guarantee of its national security.

• After the US imposed sanctions on Iran in 2010, and the EU followed in 2012, Iranian oil exports took a major hit, and Iran’s economic power declined by one-third. But were sanctions the sole factor in the nuclear deal? On the Iranian side, it is difficult to say, but it is certain that the sanctions were uppermost in Iranian decision-makers’ minds when they entered the negotiations. [Or declined to one-third? This is unclear because the indicator being used is not specified. How is economic power being measured here? Meaning growth declined to/by one-third of its previous value? Exports? Revenues?]

• The latest US sanctions on Iran do not conform to the recognized conceptual framework of sanctions, insofar as the US recognizes that Iran has complied with the agreement, but nevertheless will sanction it.

• The recent US sanctions differ from previous sanctions on the Iranian economy, leading some Iranian economists to believe that they will be more difficult to cope with than in the past.

• Of the dozens of sanctions on Iran’s economy, the UN and the EU imposed just four each; the rest were levied by the US. As the US withdraws from the nuclear deal, this means the return of all US sanctions and the addition of others.

• Although past sanctions did not have a large impact on Iran’s economy, the sanctions imposed in 2010 did, particularly when they touched financial transfers, oil, energy, tourism, and international transport.

• One of the most significant impacts of the US sanctions is to bar the production and export of Iranian oil.

• With past American sanctions, Iran’s crude oil production fell sharply. In expectation of the lifting of sanctions with the nuclear agreement, oil production increased substantially. Since most of Iran’s revenues come from oil and these revenues fund much of the state budget, the sanctions could have major economic and psychological effects on Iran.

• In the years running up to the nuclear accord, trade between Iran and the US was negligible, just $300 million, and this decreased after the agreement. The trivial amount of trade between the two countries may be one reason for Trump’s decision to withdraw from the agreement.

• Trade between the EU and Iran reached its highest level in 2017, coming in at $25 billion. In comparison, trade between the US and the EU is 30 times greater. European companies and governments are therefore likely to join the US in the sanctions on Iran.

• Iran’s economic diplomacy was inadequate in previous decades. Iran has no more than five or six major trading partners, most of them major Asian states. This makes it easier and less costly for the US and EU to impose sanctions on Iran. In contrast, Turkey has nearly 100 trading partners, making it more difficult and costly to sanction it.

• The US withdrawal from the nuclear agreement had an impact on foreign investment in more than one sector, notably curtailing the presence of foreign investors. After the sanctions, Iran faced a chain of reactions from multinational corporations and other states. Major companies like the French Total withdrew from business deals they had signed with the Iranian government. This makes the sanctions more effective and damaging.

• Economic mismanagement in past decades, rather than US sanctions, is responsible for many of Iranian economic problems. This suggests that sanctions could be dealt with if economic reforms and anti-corruption drives are successful.

• Pressure was one reason that Iranians agreed to negotiate. They may again enter into negotiations, but not in the framework proposed by Trump.

• Sanctions had a sizeable impact on social well being in Iran, both material and psychological. If the

• goal of sanctions was to pressure the Iranian people, they achieved their objective.

(1) See Al Jazeera, November 5, 2018. Accessed November 5, 2018. Click hear

(2) He was speaking at a closed conference, “Iran in 2019,” organized by the Al Jazeera Center for Studies in Doha, October 27–28, 2018.

(3) ISNA, May 22, 2018. Accessed November 6, 2018. Click hear

(4) The thesis can be accessed at https://thesis2.ut.ac.ir/thesisinfo/ThesisPdf15PagesFiles/2014-8/272753-15Page-.pdf.

(5) Al Jazeera Center for Studies, September 8, 2018. Accessed on November 6, 2018. http://studies.aljazeera.net/ar/reports/2018/09/180918094254775.html.