Between late March and early April 2019, three significant developments in North Africa captured the world imagination and raised new questions: Bouteflika’s resignation from the presidency, after a twenty-year controversial rule and an unsuccessful presidential fifth bid. Army Chief Gaid Salah’s public defection from Bouteflika has raised questions about future role of the military. Despite the Parliament’s vote on Abdelkader Bensalah, as acting President for ninety days, protests and robust civil society continue their resistance and defiance of the army. The political elite remains divided about the pursuit of a civilian government and peaceful political transition, while the traditional FLN-military alliance seeks to reposition itself in a new balance of power. A new puzzle looms in the horizon: how to negotiate a path forward in Algeria?

The second development was a double-take act of militarism after the coup d’etat that ended the 30-year rule of Omar al-Bashir and the reconfiguration of leading members of the Transitional Military Council (TMC). The Council, led first by General Ahmed Awad Ibn Auf before Lieutenant General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, sought to calm the protesters by promising the release of political detainees while the country would be under a state of emergency for three months. It also vowed to hold general elections after two years of military rule. Interim leader al-Burhan claimed the Council is “complementary to the uprising and the revolution”, and it is “committed to handing over power to the people." However, demonstrators were still, determined to remain in the street, by the third week of April, “until power is handed to civilian authority.” (1) Ahmed al-Montasser, spokesperson for the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA), which has been organizing the massive demonstrations in Khartoum and other Sudanese cities, rejects the claim of a ‘regime change’ in a post-Bashir Sudan. He asserts, “The regime remains the same. Just five or six people have been replaced by another five or six people from within the regime. This is a challenge to our people.” (2) The question now whether the army would accept to turn to the barracks?

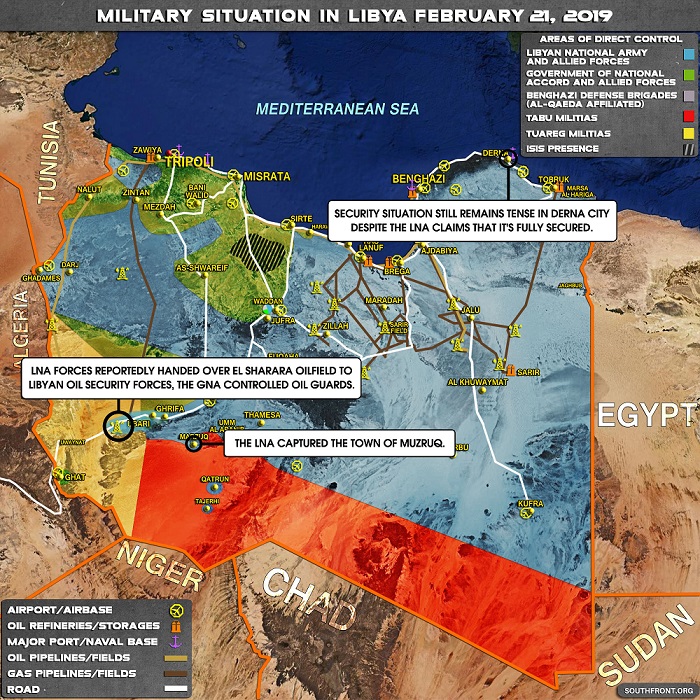

Between Sudan and Algeria, there has been a more alarming development with a strong push of militarism at the heart of the geopolitics of North Africa. Retired General Khalifa Haftar, who heads the self-styled Libyan National Army (LNA), continues his military assault against Tripoli, the headquarters of the UN-backed government of National Accord, which emerged out of the UN-brokered political transition plan for Libya, known as Libyan Political Agreement (LPA) signed December 17, 2015 in Skhirat, western Morocco. With the support of the House pf Parliament in Tobruk, Hafter’s so-called “Karama Operation” has escalated the Tripoli-Tobruk conflict of legitimacy under the pretext of eradicating ‘terrorists’ and countering human trafficking. By April 20, the death toll rose to at least 220, including combatants and civilians.

Earlier in February 2019, Haftar’s forces advanced to the lawless south, and captured Sharara, the biggest oilfield in the country. Haftar has been courted by leaders in France, Italy, Russia, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt in the last two years. France said his military operation had “eliminated terrorist targets”, and was a way to “durably hinder the activities of human traffickers.” (3)

By mid-April 2019, the United Nations became increasingly concerned with the growing international rivalries and support for competing Libyan factions, which may push Libya to the brink of full-blown war. As Stephanie Williams, deputy head of the UN mission to Libya (UNSMIL), told the Financial Times, “There are indications that material is pouring in for both sides and that is a serious escalation. This has to stop because broadening the conflict is going to be catastrophic. This is a city of three million people.” (4)

These three scenarios of military-civilian geopolitics in Algeria, Libya, and Sudan raise new questions about the validity of the emerging ‘second wave’ framework of the Arab uprisings, or the so-called ‘Arab Spring 0.2’. Should it be considered part of the same 2011-Arab political change model in an open-ended cycle of contention and collective action in Arab streets? Or possibly the divergence between the current dynamics in Algeria, Libya and Sudan is indicating some blind spots in the one-size-fits-all analysis of the Arab uprisings, not to mention the complex cases of Egypt, Yemen, and Syria.

This paper is a summarized version of my presentation at the concluding panel “North Africa: The Future outlook” at the one-day conference “North Africa: New Elections, Old Problems”. Brookings Doha Center [BDC], hosted the conference in collaboration with the Italian Ministry for Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation [Farnesina] and the Italian Institute for International Relations [ISPI], as part of the “Mediterranean Dialogues” series held this time in Doha April 17, 2019. My presentation followed three separate panels on Algeria, Libya, Tunisia, with different perspectives of nearly twenty North African, European, and Arab American analysts and scholars.

This paper aims at addressing some of the main challenges, formulated as seven propositions, which will shape the future of the region; while expanding the theme into new elections, old problems: context, dynamics and trajectory. It probes into the pros and cons of the desired electoral process as a logical step forward to establishing democratic states in North Africa. It also examines the dilemma of fragmented legitimacy, as it has been the case, since the elections of August 2014 in Libya, between the rival power centers, Tobruk in the east versus Tripoli in the west.

The current showdown continues between the disputed constitutional ‘legitimacy’ of the selection of Bensalah as interim president, by the Algerian Parliament, and the counter ‘legitimacy’ of the will of the people, or people politics. This dynamism between top-down forces and bottom-up resistance implies indirectly the need for updating our unit of analysis: state or people, military or social movement, and possibly a third variable? The paper also probes into the evolution of the protest discourse in terms of past emotionality and symbolism [2011], and current rationality and persistent sense of negotiation with the military in Algeria and Sudan [2019].

Other propositions in the paper assess the commonality, or divergence, of paths between Maghreb and Mashreq, or North Africa and the Middle East, and caution against a silo-like mode of analysis by ignoring the North-South dimension of North Africa as a conduit of several strategic choices between Europe and Africa. Since the challenges of migration, extremism, and counterterrorism have dominated recent Euro-Arab exchanges along the Mediterranean basin, the benefits of an alternative geopolitical vision, Europe-Maghreb-Africa, remains under-studied. The last proposition examines the external factor and support for rival groups as a threat, which tends to hinder the prospects of smooth transition and to push the region into a mode of stalemate and instability.

|

| [Reuters] |

New Points of Entry

Between 2011 and 2019, popular grievances against deteriorating economic conditions, high unemployment among the Arab youth, and lack of social mobility constitute a common causality of various cycles of uprisings in North Africa and the Middle East. Now, there have been protest slogans of radical regime change, eradication of corruption, demands for accountability, and persistent calls for civilian rule, whereas some foreign interventions seek to sustain certain regimes and solidify the grip of power by the military, as is the case of Libya and Sudan. The dynamism of these forces can be analyzed as common driver of the fluid Arab conflicts over the past eight years. However, the trajectories of the current episodes of political change seem to defy the one-case study-hypothesis along the distance between promising democratization and sustainable militarism.

1. The Military Position

The new cases of Algeria, Libya, and Sudan affirm the centrality of the military-civilian equation in shaping the prospects of a peaceful and smooth transition. The twist of events in Egypt, between January 2011 and July 2013, exposed a hidden strategy of the military, and showcased a setback of the democratic promise of the Uprising after General Sisi decided to put President-elect Morsi in jail. It also represented a test of pluralism in Arab politics within the big battle between militarism, secularism, and Islamism. The Egyptian case remains pivotal in analyzing subsequent episodes of the Arab political change, and accentuates the significant role of the army in supporting, or derailing, the locomotive of revolutions. One can trace similar scenarios back to Algeria after the electoral victory of the Islamic Salvation Front in 1991, Sudan in 1989, Haiti after Jean-Claude Duvalier's departure in 1986, post-Marcos Philippines in 1986, Turkey in 1980, Chile in 1973, Iran in 1953, Spain in 1936, and Mexico after the fall of Porfirio Díaz in 1911.

I still recall a private conversation over dinner with a North African foreign minister in July 2011, when he cautioned against ignoring the calculations of the Egyptian Army despite its pretense of being ‘neutral’, or acting as the ‘safeguard’ of the transitional period, during the Tahrir square popular demonstration against the Mubarak regime. Sociologist Jack Goldstone also pointed to the military factor. He wrote in his Foreign Affairs article in May 2011, “The greatest risk that Tunisia and Egypt now face is an attempt at counterrevolution by military conservatives, a group that has often sought to claim power after a sultan has been removed.” (5)

Some EU officials were skeptical of the long-term role of the Egyptian Army. For instance, Heidi Hautala, chairwoman of the European Parliament's Human Rights Sub-committee, was wary about the power of the Army. She urged the European Union “to closely follow the actions of the Armed Forces Supreme Council that is now ruling Egypt. We cannot befriend rulers or temporary military governments whose commitment for human rights is not clearly evidenced. Let us see how genuine the promises of the Egyptian Army are regarding the lifting of the state of emergency.” (6)

In contrast to this dubious scenario of Egypt, Tunisia’s military remained faithful to the Constitution during the turmoil of 2011. General Rachid Ammar—a national hero who goes by the pseudonym of “the man who said no”— described how the army “saw itself as the caretaker of the revolution and would see it through to the end.” He sent a clear message that the army “would not reprimand peaceful demonstrations, but it would suppress those that would lead to a political vacuum, because that vacuum would surely lead to another dictatorship.” (7)

This year, the Algerian military establishment seems to be standing at the intersection between the Tunisian option and the Egyptian option. Its generals and commanders remain eager to protect their interest. Army Chief Gaid Salah’s public defection from Bouteflika can be seen, as some analysts argue, as an “attempt to ingratiate the army and himself with the protesters in the hopes of surviving the revolution.” (8) Algeria observers like Camille Pecastaing of the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies in Washington argue Bouteflika’s ‘resignation’ was not as such, rather the result of “internal factional strife than people power”.

He asserts it was a corrective action that was supposed to take place ten years ago. According to Pecastaing, “the military-security apparatus had never intended for Bouteflika to last past his original reconciliation mission, but the presidency carried enough weight that the incumbent was able to re-impose his candidacy on voters not once but four times: in 2004, 2009, 2014, and initially in 2019.” (9)

|

| [Conflicts Data Base] |

2. Beyond Transitology

The new uprisings in Sudan and Algeria and Haftar’s military campaign in Libya have perplexed most political scientists and historians, notably transitologists. One of these transitologists is Marc Lynch who energized the use of the ‘Arab Spring’ meta-frame in his January 6th, 2011 Foreign Policy article. He recognizes “we are all struggling to understand these changes. Their historical novelty, dizzying pace, and rapid reversals have proven challenging to Arabs and outside observers alike.” (10) These developments in North Africa have taken analysts back to the drawing board to deconstruct essentially the role of the military establishment and other transformative institutions. They have also revived debate over the validity of an ‘Arab transitology’, within the hypothesis of a ‘universal’ theory of democratization and the possibility of studying relevant processes of democratization in various social contexts like eastern European and Latin American countries after the Cold War.

Transitology theory derives from the assumption of some overtly gradual transformation within the tradition of political science. It follows a line of inquiry shaped mainly by Euro-American theories of democratic transition. As sociologist Dankwart A. Rustow, known as the father of the transitology paradigm, explains, “the genesis of democracy, thus, has not only considerable intrinsic interest for most of the world; it has greater pragmatic relevance than further panegyrics about the virtues of Anglo-American democracy or laments over the fatal illnesses of democracy in Weimar or in several of the French Republics.” (11)

Some scholars of structuralism perceive the Arab uprisings as the “fourth wave” of democracy in the sequence of past transitions to democracy: the first wave emerged in southern Europe (Portugal, Greece, and Spain). The second occurred in Latin America (Ecuador, Peru, Chile, Argentina and Uruguay) and led to the collapse of the authoritarian states. The third wave was in the central and eastern Europe after the collapse of the Soviet Union, where democratic concepts introduced to political life in Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Romania. (12) The first three waves of change happened, as some democracy theorists argue, in areas with similar conditions of political decay, socio-economic grievances, and are the closest episodes to what has happened in MENA region.

Back in 2011, the commonality of the large-scale protests across the region and the removal of four Arab presidents then: Ben Ali, Mubarak, Ghaddafi, Saleh within a domino-like political wave, led to the belief in one unifying pan-Arab revolutionary moment in modern history. However, the Syrian conflict has gone astray with violence and struggling world diplomacy. It has entered a stalemate after the UN-brokered Geneva talks as well as the Russia-led Sochi and Astana gatherings for a reconciliation plan. There is growing skepticism toward the diplomatic maneuvering, by the UN New York, the Kremlin in Moscow, or other initiatives in the region. In contrast, the military operations on the ground are tilting toward a protracted conflict. Some observers have concluded that without reliable intermediaries on the ground to supervise so-called reconciliation processes, “stability will be ephemeral and peacebuilding unattainable.” (13) Consequently, Syria is doomed to suffer more violence for many years to come. These deteriorating conditions have morphed into the world’s “largest humanitarian crisis.” (14)

One can draw several parallels between the Syrian conflict and Libyan conflict. They have been perpetuated by subsequent cycles of violence and dominant militarism, and have revealed the UN diplomacy fatigue. The majority of Libyans feel less enthusiastic and believe the current deadlock is too strong to make any real political overtures. The only political momentum in Libya at present is the United Nations’ search for a new impetus among rival centers of power, including the militias. However, leaders of political and military rival groups are reluctant to engage in the UN process or to commit to any final decision. There is growing hopelessness regarding UN diplomacy, which has been characterized by recurring themes of “promising” dialogue and “imminent” reconciliation, proposed by five consecutive UN special envoys: Ian Martin (2011-2012), Tarek Mitri (2012-2014), Bernardino León (2014-2015), Martin Kobler (2015-2017), and Ghassan Salamé (June 2017-present). (15)

Georgetown scholar Michael Hudson illustrates a two-fold failure, “Political science has so far offered little by way of enlightenment as to the future course of the Arab Uprisings. It has disappointed us in two ways: “persistent authoritarianism” did not prepare us for the Uprisings, and “transitology” seems too-limited ‘fair weather” approach to what has emerged as a confusing and diverse post-Uprising environment.” (16)

3. Addressing the 3-C Dilemma

The current popular defiance in Algiers, Tripoli, and Khartoum against the return to militarism contests the monopoly of certain elite and the failure of local socio-economic policies.

Former presidents Bouteflika and Bashir adopted an ill-sighted decision-making mandate in favor of what I term as the 3-C dilemma: cronyism, clientelism, and corruption. This dilemma explains how mutual dependency between the ruling elite, certain financers, and generals is essential in modifying those regimes from authoritarianism into neo-authoritarianism. Peace studies founder Johan Galtung blames certain structures of causing societal imbalances and socio-psychological tension within individuals or what he calls “structural violence.” He conceives structural violence as a type of violence built into the social structure and “should exhibit a certain stability: social structures may perhaps sometimes be changed overnight, but they may not very often be changed that quickly.” (17)

Like other Arab capitals, Algiers and Khartoum have maintained the power of their old-boys’ club, or golden circle of state backers, to help smoothen the transition. Political scientist Francis Fukuyama has seen this pattern elsewhere in modern history; “While modern political orders seek to promote impersonal rule, elites in most societies tend to fall back on networks of family and friends, both as an instrument for protecting their positions and as the beneficiaries of their efforts. When they succeed, elites are said to “capture” the state, which reduces the latter’s legitimacy and makes its less accountable to the population as a whole. (18)

Still, the scale of Algeria’s intended reforms remained below the expectations of the masses. By mid-April, twelve Algerian businessmen associated with Bouteflika, including billionaire Ali Haddad, were arrested in a move which may give some indicators of decisiveness against corruption in the eyes of the protestors. As one analyst predicts, “Gaid Salah may next have to scapegoat other elements of the gang, including the “three B’s”: Prime Minister Noureddine Bedoui, soon-to-be interim president Abdelkader Bensalah, and the head of the Constitutional Council, Tayeb Belaiz who resigned April 17.” (19)

Accordingly, the trajectory of current protests in Algiers, Tripoli, and Khartoum should not be analyzed through a linear perspective; but rather within a chain of strategic actions, reactions, and counter-reactions of various stakeholders at the domestic, regional, and international levels. Complexity theory provides an explanatory framework for the study of interrelated factors and dependencies, and helps explain why interventions may have un-anticipated consequences. The intricate inter-relationships of elements within a complex system give rise to multiple chains of dependencies.” (20)

The following seven propositions address the main lessons learned since 2011 and aim at shading some light on future challenges in North Africa transformation.

Proposition 1: Limitations of the Electoral Process

Most transitologists agree on three consecutive steps for the democratization process to function in light of their forty-year focus on democratization studies: First, the achievement of liberalization and the opening of the authoritarian regime as in the context of Arab states. Political scientist Sheri Berman points to the dawn of a promising new era for the region, and it will be looked at down the road as a historical watershed, even though the rapids downstream will be turbulent. (21)

Second, the pursuit of political reforms and regular elections paves the way for democratic governments to rise to power. The Arab experimentation with non-rigged elections, for the first time in 2011 and 2012, restored some trust among millions of Arab voters who waited for hours outside the polling centers on hot days to cast their votes across Tunisia, Egypt, and other countries. Third, the last phase is expected to generate some consolidation of the democratization process over a long-time framework. It presupposes state institutions would embrace the norm of political legitimacy and civil society gains more strength and momentum vis-à-vis the political elite. This final phase should solidify the overall acculturation of society to the democratic model.

Nowadays, there is strong sentiment among most Arabs that the ballots have not fulfilled the desired democratization phase. Once again, the electoral process has been undermined by the return to militarism and growing security paradigm in Sudan and Libya, as a déjà vu scenario of Egypt, amidst fear of duplicating the same move in Algeria. Moreover, the whole picture reveals how the Arab region has made a step backward with the emergence of new forces of tribalism, sectarianism, militarism, and political violence, driven by the narcissism of small differences, between Shiites and Sunnis, Muslims and Islamists, or radicals and modernists.

|

| [AlJazeera] |

Tunisia, the most celebrated model of the Arab uprisings, was perceived as a case of potential pluralism, inclusive politics, and prevention of a political impasse or derailment into violence. Since early September 2017, the momentum of reform has been shaken up by three controversial decisions made by Prime Minister Youssef Chahed: 1) the appointment of some of Ben Ali’s former ministers to a new cabinet after a government reshuffle; 2) the adoption of the so-called “administrative reconciliation” law by the parliament regarding corruption during Ben Ali’s presidency; and 3) the postponement, once again, of the municipal election. Essebsi had made big strides by supporting the idea of granting women equal rights in inheritance and legitimizing mixed marriages between Tunisian women and non-Muslim citizens of other countries. He was heralded as the leader of reformism and “the good Arab revolutionary of the moment” after his victory by 55.68 percent of the vote in the 2014 election.

However, the Tunisian public opinion remains cynical about the government’s claim of efficiency and pragmatism. Tunisia now faces a hard choice between stability and justice in handling its legacy of corruption and power abuse. A sizable majority of 89 percent of Tunisians believe corruption in Tunisia is worse now than it was prior to 2011. Consequently, President Essebsi and his Nidaa Tounes Party are running the risk of deepening disarticulation between the government and young Tunisians who are frustrated by the lack of economic reform and agitated about partisan politics. They belong to a generation that is breaking long-held fears, but they remain captive to long-term unemployment. (22)

In Morocco, the silent big elephant in the room, has been embroiled by frequent protests in the northern region Rif, miners’ strike in Jrada, doctors’ and teachers’ strikes since early 2017. There has been also an open-ended battle between the state-backed Authenticity and Modernity Party, founded by Fouad Ali El Himma, advisor to King Mohammed VI, and the Islamist Justice and Development party, after a six-month political void known as ‘Blockage’ against the premiership of its leader Abdelilah Benkirane, after the legislative elections held in October 2016. Now, the dominant Makhzen has decided to invest in the National Rally of Independents (RNI) as the new “black horse”, after substituting its leader Salahedine Mezouar by the wealthy agriculture minister Aziz Akhenouch, to sail through to the next election. However, Benkirane, the PJD’s ex-prime minister has promised a hard fought election in 2021.

Back in April 2017, I foresaw how the situation in Libya was not in favor of the UN’s plan of holding new elections in the spring 2019. I wrote then, “Like many Libyans, most politicians are less hopeful of the feasibility of election next spring. There is a sense of diplomacy fatigue after holding scores of meetings in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and elsewhere; and none of the signed agreements have been fully implemented. There have been reoccurring themes of ‘promising’ dialogue and ‘imminent’ reconciliation, proposed by five consecutive UN special envoys.” (23)

A growing number of North Africa scholars have abandoned the framework of transitology for transformation. Steven Heydemann defends the term “transformation” since it captures the notion of “systemic change yet without implying directionality or some form of democratic teleology. It emphasizes the fluidity and unpredictability of transformational settings.” (24) He argues, “Conceptualizing the Arab uprisings as transformational processes without imposing on them either the expectation that they will take the form of democratic transitions or that they can be adequately explained simply as cases of failed democratization is important for avoiding deterministic or essentialist traps.” (25)

Instead of considering the mass protests and toppling or killing six presidents [Ben Ali, Mubarak, Ghaddafi, Saleh, Bouteflika and Bashir] so far, it is high time to shift from the use of a tally sheet to the study of unique experiences and separate destinies of different tracks of social change. Despite the frequent electoral processes in North Africa in the last years, they have not served as a compass toward a smooth transition or management of the majority-minority game through the ballots.

Harvard economist Eric Chaney relates this setback to the determinants of the Arab world’s democratic deficit. He argues that inasmuch as the region’s institutional history is useful for forecasting the future, it suggests “democracy is less likely to emerge where political power remains largely divided between religious leaders and the military to the exclusion of other groups.” (26) Once again, the current dynamics in Algeria, Libya, and Sudan indicate Arab political systems are “veering in some sharply different directions”. (27)

Proposition 2: Fragmentation of Political Legitimacy

The new buzzword nowadays in North Africa is legitimacy. Protestors, professional associations, civil society organizations, and the establishment in Algeria, Sudan, and even in Libya have defended distant frameworks of political legitimacy. The current controversy over political legitimacy undermines, as discussed earlier, the potential of the desired consolidation of the anticipated three steps of the democratization process in other Arab countries.

The clash between the protestors’ and army general’s narratives has deepened the fragmentation of legitimacy. New variations of legitimacy have emerged in the public discourse such as Shar’iya thawriyya (revolutionary legitimacy), Shar’iya intikhabiya (electoral legitimacy), Shar’iya sha’biya (legitimacy of the street in reference to the “people”), and Shar’iya tawafuqiya (consensual legitimacy). This clash puts the region at limbo: how to reconcile the conflict between two main schools of thought: power politics versus people politics, a claimed constitutional framework of transition [e.g. Article 102 of the Algerian constitution) and the tabula rasa, or clean slate, demand of protestors.

For instance, the Algerian case has come to a crossroads of state building. Lahouari Addi of L’Institut d’Etudes Politiques de Lyon argues, “The specificity of the Algerian regime is that, at the State’s cupola is a bicephalous structure in the form of a legitimising real power belonging to the military hierarchy, and a formal power that directs the government administration and state institutions. This duality is a heritage of the War of Independence, during the course of which the military personnel of the National Liberation Army (ALN) took the upper hand over the civilians of the National Liberation Front (FLN).” (28)

The outcry for legitimacy has been louder in Sudan. The African Union (AU) has denounced the military takeover, and protesters are still in the streets demanding civilian rule. Some analysts have expressed skepticism about the alleged ‘coup d’etat’ against President Bashir. Nandita Balakrishnan of Stanford University focuses on her research project on how autocrats have left power since the end of World War II. She found they tend to choose negotiated settlements preemptively, out of the other choices of coups or elections, rather than gambling on hanging on to power by trying to prevent or survive conventional coups. She wrote, “A gray-zone coup occurs when the military must use more coercion to force a negotiated settlement, thereby falling in the gray zone between a negotiated settlement and a conventional coup.” (29)

The legitimacy narrative remains inspiring for protesters in Khartoum in maximizing pressure against the Transitional Military Council (TMC) for a civilian rule. It has also highlighted the international community’s firm stance against the pursuit of militarism in the country. The European Union has supported the African Union’s call for handover of the power to a civilian-led transitional authority in a two-week ultimatum. The EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini said at the plenary session of the European Parliament “As long as the transition is not managed by civilians, the European Union will not recognize the legitimacy of the Transitional Military Council.”

|

| [Reuters] |

In the case of Libya, the outcome of the last two elections has shattered the construct of legitimacy. The first ballot was held in July 2012 to elect the General National Congress (GNC) with the mandate of forming a constituent assembly to write a new constitution. The second ballot took place June 25, 2014 to elect the House of Representatives, with a 30-seat quota for women and a total of 200 seats. The public turnout was very low at 18 percent. New members of the House suspected the powerful militias of Misrata were controlling the GNC, from which they refused to take office in Tripoli, and decided to establish their own parliament in the eastern city of Tobruk.

Still, the United Nations Special Mission to Libya (UNSMIL) made to recommendation to the international community to recognize the House of Representatives (HoR). This decision has set Libyan politics on two rival tracks of political legitimacy. Some Libya observers have pointed out, “The first and most important is to avoid conferring legitimacy on one side over the other through expressions of support for “state institutions” or “elected bodies”: although the HOR was originally an elected legislature, it is now a rump parliament that represents one side in an ongoing conflict.” (30)

While serving on the UN Panel of Experts, I could sense closely the fierce showdown between two lines of international recognition bestowed on leaders like al-Sarraj in the west, HoR in the east, and the exercise of power - legitimate or otherwise - on the ground. The lack of UN diplomatic progress has derived also from the unsettled controversy surrounding Haftar and his military machine, and the trajectory of the political and military support he has secured from countries like neighboring Egypt, UAE, Saudi Arabia, France, and Russia.

Proposition 3: What New Unit of Analysis?

The personal connection between demonstrators, self-motivation to protest, slogans, and demands for jobs and dignity implies the combination of material low needs and non-material high needs. As conflict theorist John Burton asserts, “It will be seen that consideration of a human element has extensive implications and is basic to thinking about the nature of conflict and its resolution. If there are human needs that have to be accommodated, then conflict control will have to give way to quite different processes which seeks the source of conflict and the environmental conditions that promote conflict, leading to institutional change. Conflict will have to be defined as a problem to be resolved rather than a situation in which behaviors have to be controlled.” (31)

Despite the power struggle in the current conflicts in North Africa, the focus should not be on either side of the conflict as top-down status quo, with some cosmetic alterations of certain political figures, or bottom-up calls for radical change. For instance, a civil society collective of Algerian associations and unions dubbed, "For a peaceful way out of the crisis", has pointed out, "Recent developments and signals sent by the system confirm the continuation of the 'clan transition' option, in reference to the networks of the former Department of Intelligence and Security (DRS) which was disbanded in 2016.

What matters here is neither the grandiosity of the protests, nor the magnitude of the establishment resistance or gradual concessions. Instead, it is high time to shift to a new unit of analysis: the human dimension and changing demographics, in addressing the military-civilian dialectic, growing role of protestors, momentum of civil society organizations, and North African diaspora. For example in Algeria as Pecastaing points out, “The street may detest Le Pouvoir but there is no structure to stand against it. Algerians show an exceptional level of distrust for authorities and institutions, perceived to be corrupt and dictatorial. The mindset is a mix of conspiratorial paranoia and apathetic rage, of hatred and despair.” (32)

Amidst the current tit-for-tat between protestors and the establishment, social movement and the army, or people and state, the sequence of events in Algiers, Tripoli, and Khartoum has highlighted the relational aspect of strategy/counter-strategy, or what can be termed as relationsim, in shaping a new balance of power at the crossline between protestors and the police. The human dimension has broken away from fear, and is now energizing its frames of robust people politics, whereas traditional centers of power are losing the political capital of legitimacy.

So far, no charismatic leader has emerged from the Arab uprisings to guide the masses forward. These projects of political change need well-enlightened leaders and organic critical intellectuals. Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci once wrote, “all men [sic] are “philosophers”’ insofar as everyone has a specific conception of the world, a “worldview” which they have forged out of their experience and circumstance. The task was to develop philosophy, both in its specialised form as scholarship and in its everyday form, into “critical awareness.” (33)

Proposition 4: Evolution of the Protest Discourse

The current dynamics in Algeria, Libya and Sudan highlight the evolution of the Arab protest movement. Between 2011 and 2019, the motto of collective action Irhalism (derived from the slogan " ارحل "[Irhal] [Degage, French]; [Get out, English] has shown some maturity of less emotionality. It represented a new global social movement which has emerged in a wide multicultural and globalized sphere. The slogans Ashaab yourid (The people wants) and Irhal, as new frames of non-violent protest, were adopted by protestors in other parts of the world. They embody a new sociological prototype of protestor: “The Graduate with no Future”.

As I wrote in a previous publication, Irhalism has become synonymous to peoplehood politics worldwide, and seems to shape a new social movement theory as it aspires for a moral philosophy in contemporary politics. It has captured the imagination of many political sociologists with the novelty of non-traditional social actors who have mastered the narrative of change and gained social power from the fading public belief in the Hobbesian social contract theory. Irhalism has also energized new hopes for cosmocracy, which perceives the political evolution of civil societies above the state’s boundaries in the pursuit of cross-border global governance. (34)

Instead of commemorating the legacy of Mohamed Bouazizi whose death in Sisi Bouzid was the spark that ignited the first Arab uprising in Tunisia, or romanticizing the emotional sentiment in Tahrir square in January in 2011, protestors in Khartoum have chanted newly-constructed slogans, such as "freedom, peace and justice", "revolution is the people’s choice", and “Just fall – that is all" ( تسقط – بس tasqu ṭ bas). Their Algerian peers have been passionate: "Down with the System!", "You ate the country, you bunch of thieves", and "They must go. The Bs must go."

|

| [AlSharq Alawsat] |

There has been also a gender shift in the symbolism of the protests. For instance, young Sudanese women, like Alaa Salah, have become called ‘kandakas’, the title of the queens of ancient Sudan. Alaa stood on the top of a car chanting an inspiring song of revolution and became the uprising’s iconic image. From a comparative perspective with 2011, the current protests seem to be well-pointed and less emotional. Their symbolic dimension, in text or imagery, tends to be rational and coherent in demanding radical change and rejection of a military rule. This shift could be a step forward to more strategic frames in the next round of Arab protests.

Proposition 5: New Line of Demarcation

Any projection of future shifts in Algeria and Libya, more than Sudan, would be significant in reconstructing the relationship between Maghreb and Mashreq. The Algerian-Libyan borders constitute now more than one level of geopolitics in the region. On April 17, 2019, the Algerian army conducted the so-called "The Bright Star 2019" ammunition exercises in the area of In Amenas near the Libyan border, under the supervision of the Chief of Staff, Lieutenant General Ahmed Kayed, “in circumstances close to the reality of real battles”, two weeks after the outbreak of armed clashes in western Libya. (35)

As Alia Brahimi points out, “The Algerians have long been suspicious of the renegade general’s [Haftar] claims to be a force for stability and favoured a negotiated political settlement to the Libyan crisis that would secure the 600-mile shared border. But in the last two months, domestic protests and the resignation of the Algerian president, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, have preoccupied the Algerian military – perhaps the only force in the region with a deterrent effect on Haftar.” (36)

During the three-month transitional period [April-June] in Algeria, any violent incident which may occur on these borders and will turn into legitimate justification for the Algeria army, as the sole protector of the national security, to intervene and call for a state of emergency. As one analyst put it, “A military popular enough to referee the upcoming transition will make democratization much more difficult.” (37)

The Algerian-Libyan borders have another strategic significance should Algeria maintain the course of peaceful path toward democratization, following the example of Tunisia. They may define some Maghreb exceptionalism in terms of peaceful and smooth transformation of Arab societies. Geo-political scientists may accept my proposed line of demarcation in conceptualizing the Maghrebi tendency toward peaceful transition, civilian rule, and non-militarization of politics; whereas Mashreq, or the Middle East, has drifted into open-ended civil wars in Syria and Yemen, sectarianism in Iraq, militarism in Egypt, and other aspects of non-inclusive politics.

|

| [Disclaimer] |

Such a debate echoes the classical exchange about the philosophical turn Maghreb took in the late 12th century when it found resonance in the rational philosophy Ibn Rushd (Averros), as he energized Aristotelianism, mainly in book “Tahafut al Tahafut” (Incoherence of Incoherence), published in 1150. However, Mashreq had favored the traditional non-critical ideas of Abu Hamid Ghazali and his 1095 book Tahafut al Falasifa (Incoherence of Philosophers). The two men had different interpretations of the position of philosophy and critical thinking in formulating mantiq [logic], or what Mohamed Abed Al-jabri critiqued as “Arab reason” in late 20th century.

Libya now is at crossroads now; and the outcome of Haftar’s military campaign against Tripoli will decide whether it confirms Libya’s Maghrebi spirit of change, or what Philip Naylor calls “exceptional cultural unity” (38) ,or may follow the path of Mashreq.

Proposition 6: North Africa’s New Geostrategic Position

Halford Mackinder (1861 –1947), the so-called father of geopolitics, is often credited with introducing two new terms into the English language: "manpower" and "heartland". In 1920s, he perceived the Earth's land surface as three divided spheres of interconnectedness: 1) the World-Island, comprising the interlinked continents of Europe, Asia, and Africa. This was the largest, most populous, and richest of all possible land combinations; 2) the offshore islands, including the British Isles and the islands of Japan; and 3) the outlying islands, including the continents of North America, South America, and Australia. He presumed "Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland; who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island; who rules the World-Island commands the world." (39) He argued then “Whether we think of the physical, economic, military, or political interconnection of things on the surface of the globe, we are now for the first time presented with a closed system.” (40)

Between 1919 and 2019, several political storms have targeted the southern part of the Mediterranean Sea. The recent trend of pacifism in Algeria and growing militarism in Libya and Sudan have triggered new political uncertainties. The 2019 reality of North Africa, the Middle East and the entire Mediterranean basin, which Mackinder excluded from his conceptualization of the ‘Heartland’, have become the new epicenter of change and geostrategic complexity. He acknowledged “each century has had its own geographical perspective.”

One can update Mackinder’s hypothesis by highlighting the geopolitical significance of the region in various dimensions: East-West, North-South relations and the open-ended challenges of migration, development, trade, extremism, counterterrorism, and other Euro-North African pending hot issues. The interior of the African continent is no longer perceived as “a blank”; and the Sahara has broken away from the colonial stereotype of, as Mackinder romanticized in 1919, “the most unbroken natural boundary in the world; throughout history it has been a barrier between the white and the black men.” (41)

In their introductory chapter “EU-North Africa Relations at the Age of Turbulence”, Brookings analysts Adel Abdel Ghafar and Anna Jacobs point out that “key EU member states, such as France, Spain, and Italy, maintained enormous influence in the post-colonial period, but the EU as an institution had difficulty developing a comprehensive policy toward the southern Mediterranean region.” (42) Moreover, The Euro-North African relations have been juxtaposed by three main trends of strategy: control of migration and human trafficking, counterterrorism, and securitization of the Mediterranean basin, more than the promise of free trade and other aspects of positive engagement.

There is a risk of conducing EU-North African relations into these frameworks of fear and skepticism. Instead of positioning North Africa as wall against migration or checking point of security, the EU-North African relations would benefit from a wider scope of cooperation.

To quote Mackinder again, the map habit of thought is “no less pregnant in the sphere of economics than it is in that of strategy.” (43) Dimitris Avramopoulos, European Commissioner for Migration, Home Affairs and Citizenship, has expressed the need for “long-term, sustainable alliances with our key partners — and with Africa in particular.” North Africa has good potential to become an economic hub, and a conduit of development across Africa. It is high time for the EU to reconcile its separate policy tracks vis-a-vis North Africa and Sub-Saharan

Proposition 7: The Leave-North-Africa-Alone Paradigm

According to the World Health Organization, at least 220 individuals were killed and ad more than 1000 other were wounded in the recent fighting on Tripoli’s outskirts as of April 20. Haftar’s forces have faced robust resistance against the air and ground attacks to capture the capital. As one German Libya observer put it, “Haftar did not want to be part of the solution. He wanted to be the solution.”

Two days earlier, General Haftar received a phone call from US President Donald Trump who expressed U.S. support for Haftar’s stance against terrorism. A White House statement said: "The President recognized Field Marshal Haftar's significant role in fighting terrorism and securing Libya's oil resources, and the two discussed a shared vision for Libya's transition to a stable, democratic political system." Some critics have cautioned against what could be a misguided move of Trump. For instance, David Andelman, executive director of The RedLines Project, argues “The Trump administration risks putting itself in an untenable situation of backing two horses in the same race -- the recognized government of Libya and the rebels knocking at the door of the capital.” (44)

In Europe, French president Emmanuel Macron contributed to the political rise of Haftar when he invited him and Fayez al-Sarraj, head of the internationally-recognized government, to a “peace summit” in Paris July 25, 2017; and bestowed him the official recognition of a “legitimate political actor.” (45) Alia Brahimi, co-founder of Legatus Global and former research fellow at Oxford University and the London School of Economics (LSE), explains how Haftar has gradually been repositioned from “parochial warlord to counter-terrorism partner to potential power-sharer. Steadfast external alliances, in particular with Egypt and the UAE – the latter boasting a formidable lobbying capability – combined with diplomatic fatigue on the part of western powers dispirited by political deadlock to give Haftar this status.” (46)

|

| [La Stampa] |

Another injection into Haftar’s muscle was his meeting with Saudi King Salman in Riyadh, March 27, 2019, to receive “assurances of the Kingdom’s keenness for the security and stability of Libya.” (47) Several sources have revealed Saudi Arabia has pledged millions of dollars as aid for Haftar’s forces. The Wall Street Journal reported, “Haftar accepted the recent Saudi offer of funds, according to the senior Saudi advisers, who said the money was intended for buying the loyalty of tribal leaders, recruiting and paying fighters, and other military purposes.” (48)

UN reports have previously named the UAE and Egypt as being among countries that violated the arms embargo in Libya. Wolfram Lacher, a Libya expert at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs, explains how Haftar would not be a player today “without the foreign support he has received. The last few months, pretty much everyone jumped on the Haftar train.” (49)

In Sudan, many opposition politicians and protesters have rejected the Saudi and Emirati assistance offer of $500 million to be deposited at the Sudanese central bank. This offer is part of 3bn dollars' worth of aid to the Transitional Military Council. The objective, as the Saudi Press Agency wrote, “is to strengthen its [Sudan] financial position, ease the pressure on the Sudanese pound and increase stability in the exchange rate." (50)

What is alarming are these international interventions, or linkages. Now, a bad scenario is emerging through the combination of Emirati-France-American strategies to help duplicate the Sisi model in North Africa. While developing his new protracted social conflict [PSC] theory in 1990, Arab-American conflict theorist Edward Azar argued, “Protracted social conflicts occur when communities are deprived of satisfaction of their basic needs on the basis of the communal identity. However, the deprivation is the result of a complex causal chain involving the role of the state and the pattern of international linkages. Furthermore, initial conditions (colonial legacy, domestic historical setting, and the multi-communal nature of the society) play important roles in shaping the genesis of protracted social conflict.’ (51)

Conclusion

Like other post-Uprising Arabs societies, Algeria and Sudan are struggling with the growing tension between militarism, secularism, modernism, and Islamism. This can be considered a historically liminal period. This liminality captures the quality of ambiguity or disorientation. They are at an interval between a pre-axial and post-axial age in politics, culture, and religion toward an Arab modernity through a potential Axial Age. An Arab Axial Age can be conceived as an in-between period; a period where old certainties lost their validity and new ones were still not ready. German psychiatrist and philosopher Karl Jaspers (1883-1969) describes Achsenzeit (axis time or axial age) as “an interregnum between two ages..., a pause for liberty, a deep breath bringing the most lucid consciousness.” (52)

The repertoire of the new social movement has empowered several micro narratives that echoed throughout the region and embraced shared visions of the future. They have destabilized several political structures by protesting at public squares and through new media. Subsequently, they have formulated the notion of an Arab civic republicanism in a region deeply-rooted in various systems of sultanism, emirism, militarism, and other forms of absolute power.

Most North Africans agree that the will-to-defy the state, the end of fear and humiliation by the authorities, and glorification of the ruler are among the top accomplishments of the Uprisings. In light of these shifts and challenges, the future will depend a numbers of factors: internal and external. Algeria, Libya, and Sudan’s fragile equilibrium is now in the hands of the army and the extent of foreign manipulation in favor of solidifying status quo politics.

Despite all political and ideological differences, Sudanese, Libyans, Algerians, like other North Africans can argue, engage in heated debates, and, manage to reconcile their differences. Should they be left alone to address their own problems, North African cultural tendencies, be tribal, Islamic, moderate, or rational, have often affirmed the wisdom of peaceful agreement and societal responsibility in forging new forms of tolerance and coexistence. The summer of 2019 is another good opportunity to prove such wisdom and reject all foreign conspiracies.

|

|

|

| Some of the Participants at the “North Africa: New Elections, Old Problems”. conference hosted by Brookings Doha Center [BDC], the Italian Ministry for Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation [Farnesina] and the Italian Institute for International Relations [ISPI], as part of the “Mediterranean Dialogues” series . |

1. Reuters, Sudan: huge crowds call for civilian rule in biggest protest since Bashir ousting, April 19, 2019 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/apr/19/sudan-huge-crowds-call-for-civilian-rule-in-biggest-protest-since-bashir-ousting

2. Burke, Jason. “Sudan Protesters Reject Army Takeover after Removal of President”, The Guardian, April 11, 2019 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/apr/11/sudan-army-ousts-bashir-after-30-years-in-power

3. England, Andrew. “International rivalries are driving Libya towards war, UN warns”, the Financial Times, April 19, 2019 https://www.ft.com/content/71133c4e-61ae-11e9-b285-3acd5d43599e

4. England, Andrew. “International rivalries are driving Libya towards war, UN warns”, the Financial Times, April 19, 2019 https://www.ft.com/content/71133c4e-61ae-11e9-b285-3acd5d43599e

5. Goldstone, Jack. “Understanding the Revolutions of 2011,” Foreign Affairs, May/June 2011.

6. eigh Phillips, “Ashton endorses army as 'guardians' of Egypt's transition,” EU Observer, February 11, 2011.

7. Paula Meja, “Guardians of the Revolution?,” The Majalla, March 1st, 2011.

8. Grewal, Sharan. “Why Algeria’s army abandoned Bouteflika”, The Washington Post, April 10, 2019 https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/04/05/why-algerias-army-abandoned-bouteflika/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.6f3317579171

9. Pecastaing, Camille. “Algeria’s False Spring?, The American Interest, April 12, 2019 https://www.the-american-interest.com/2019/04/12/algerias-false-spring/

10. Lynch, Marc. The Arab Uprising: The Unfinished Revolutions of the New Middle East, Public Affairs, March 27, 2012.

11.Rustow, Dankwart A. “Transitions to Democracy: Toward a Dynamic Model,” Comparative Politics, Vol. 2, No. 3, Apr., 1970, pp. 337-363.

12. Foran, J. Theories of Revolutions Revisited: Toward a Fourth Generation. Sociological Theory, Vol.11, No. 1, March 1993.

13. Hall, Natasha, “The Aftershocks of Reconciliation in Syria: Reflections on the Past Year”, Atlantic Council April 19, 2019 https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/syriasource/the-aftershocks-of-reconciliation-in-syria-reflections-on-the-past-year

14.Gladstone, Rick. “U.N. Envoy for Syria Seeks to Resume Peace Talks,” The New York Times, July 29, 2015.

15. Cherkaoui, Mohammed. Fits and Starts Characterize UN Mediation in Yemen, Syria, and Libya, Arab Center DC, February 18, 2018 http://arabcenterdc.org/policy_analyses/fits-and-starts-characterize-un-mediation-in-yemen-syria-and-libya/

16. Hudson, Michael. Al-Sumait, Fahed. and Lenze, Nele. (eds) The Arab Uprisings: Catalysts, Dynamics and Trajectories, Rowman and Littlefield, 2015, pp. 42-43.

17. Galtung, Johan. “Violence, Peace, and Peace Research,” Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 6, No. 3 (1969), p. 173.

18. Fukuyama, Francis. Political Order and Political Decay: From the Industrial Revolution to the Globalization of Democracy, Farrar Straus Giroux, 2014, p. 27.

19. Grewal, Sharan. “Why Algeria’s army abandoned Bouteflika”, The Washington Post, April 10, 2019 https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/04/05/why-algerias-army-abandoned-bouteflika/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.6f3317579171

20. Mitleton-Kelly, Eve. Ten Principles of Complexity and Enabling Infrastructures. Complex Systems and Evolutionary Perspectives on Organisations: The Application of Complexity theory to Organisations. s.l. : Elsevier, 2003

21. Berman, Sheri. “The Promise of the Arab Spring: In Political Development, No Gain without Pain,” Foreign Affairs, January/February 2013.

22. Cherkaoui, Mohammed. “Challenges to Tunisia’s Transition to Democracy”, Arab Center DC, November 21, 2017 http://arabcenterdc.org/policy_analyses/challenges-to-tunisias-transition-to-democracy/\

23. Cherkaoui, Mohammed. “Fits and Starts Characterize UN Mediation in Yemen, Syria, and Libya”, Arab Center DC, February 18, 2018 http://arabcenterdc.org/policy_analyses/fits-and-starts-characterize-un-mediation-in-yemen-syria-and-libya/

24. Heydemann, Steven. “Explaining the Arab Uprisings: transformations in Comparative Perspective”, Mediterranean Politics, Volume 21, 2016, Issue 1

25.Heydemann, Steven. “Explaining the Arab Uprisings: transformations in Comparative Perspective”, Mediterranean Politics, Volume 21, 2016, Issue 1

26. Chaney, Eric. Democratic Change in the Arab World, Past and Present, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring 2012; 42(1):363-414, p. 367.

27.Brown, Nathan. “Arab Uprisings: New Opportunities for Political Science,” POMEPS, June 12, 2012, p. 10.

28. Addi, Lahouari. “Algeria and its Permanent Political Crisis”, Geographical Overview – Maghreb https://www.iemed.org/observatori/arees-danalisi/arxius-adjunts/anuari/med.2015/IEMed Yearbook 2015_Panorama_Algeria_LahouariAddi.pdf

29. Balakrishnan, Nandita. “Sudan’s upheaval is the latest example of a ‘gray-zone coup’”, The Washington Post, April 17, 2019 https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/04/17/sudans-upheaval-is-latest-example-gray-zone-coup/?utm_term=.b421f7597217

30. Wehrey, Frederic. and Lacher, Wolfram. “Libya's Legitimacy Crisis: The Danger of Picking Sides in the Post-Qaddafi Chaos”, Foreign Affairs, October 6, 2014 https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/middle-east/2014-10-06/libyas-legitimacy-crisis

31. Burton, John W. Conflict Resolution: the Human Dimension, The International Journal of Conflict Resolution, January 1998, Volume 3, Number 1 http://www.gmu.edu/programs/icar/ijps/vol3_1/burton.htm

32. Pecastaing, Camille. “Algeria’s False Spring?, The American Interest, April 12, 2019 https://www.the-american-interest.com/2019/04/12/algerias-false-spring/

33. Gramsci, Antonio. The Modern Prince and other writings. London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1967, P. 58

34. Cherkaoui, Mohammed. What is Enlightenment? Continuity or Rupture in the Wake of the Arab Uprisings, Lexington Books, 2016

35. Alharathy, Safa. Ministry conducts ammunition exercises near Libyan border,” the Libya Observer, April 17, 2019 https://www.libyaobserver.ly/inbrief/algerian-defence-ministry-conducts-ammunition-exercises-near-libyan-border

36. Brahimi, Alia. “Arms cannot end Libya's agony – whatever its would-be strongman claims”, The Guardian, April 18, 2019 https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/apr/18/libya-crisis-military-strongman-khalifa-haftar-tripoli

37. Grewal, Sharan. “Why Algeria’s army abandoned Bouteflika”, The Washington Post, April 10, 2019 https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/04/05/why-algerias-army-abandoned-bouteflika/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.6f3317579171

38.Naylor, Phillip C. North Africa: A History from Antiquity to the Present, University of Texas Press, 2009, p. 107

39.Mackinder, Halford. Democratic Ideals and Reality, National Defense University Press, 1942, p. 150

40. Mackinder, Halford. Democratic Ideals and Reality, National Defense University Press, 1942, p. 21

41. Mackinder, Halford. Democratic Ideals and Reality, National Defense University Press, 1942, pp. 55-57

42. Abdel Ghafar, Adel. and Jacobs, Anna. “EU-North Africa Relations at the Age of Turbulence”, in The European Union and North Africa; Prospects and Challenges, (ed.) by Adel Abdel Ghafar, Brookings Institution Press, 2019, p. 3

43. Mackinder, Halford. Democratic Ideals and Reality, National Defense University Press, 1942, p. 16

44. Andelman, David A. “Trump Can't Straddle Two Horses in this Civil War”, CNN April 18, 2019 https://edition.cnn.com/2019/04/17/opinions/trump-two-horses-libya-civil-war-andelman/index.html

45. Brahimi, Alia. “Arms cannot end Libya's agony – whatever its would-be strongman claims”, The Guardian, April 18, 2019 https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/apr/18/libya-crisis-military-strongman-khalifa-haftar-tripoli

46. Brahimi, Alia. “Arms cannot end Libya's agony – whatever its would-be strongman claims”, The Guardian, April 18, 2019 https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/apr/18/libya-crisis-military-strongman-khalifa-haftar-tripoli

47. Saudi King Salman meets Libya's General Haftar, Reuters, March 27, 2019 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-saudi-libya/saudi-king-salman-meets-libyas-general-haftar-idUSKCN1R80YV

48. Malsin, Jared. and Said, Summer. “Saudi Arabia Promised Support to Libyan Warlord in Push to Seize Tripoli”, the Wall Street Journal, April 12, 2019 https://www.wsj.com/articles/saudi-arabia-promised-support-to-libyan-warlord-in-push-to-seize-tripoli-11555077600?emailToken=3df194cc56bb0732b7d2abce64637ee9uHqNU25ighb3wmdyR 2iwA3Gqpre3EPUUgjg9cPQr7XylQg8NYSapsF0vYmRGwbjZYrmwBLPVaD4zCMS/24aeFuEhqeyl7hNwIBU61U7ymW pW9hgy5kd993nerGtCYPdOEMjVs EnJQt66AhjvwTA==&reflink=article_gmail_share

49. Malsin, Jared. and Said, Summer. “Saudi Arabia Promised Support to Libyan Warlord in Push to Seize Tripoli”, the Wall Street Journal, April 12, 2019 https://www.wsj.com/articles/saudi-arabia-promised-support-to-libyan-warlord-in-push-to-seize-tripoli-11555077600?emailToken=3df194cc56bb0732b7d2abce64637ee9uHqNU25ighb3wmdyR 2iwA3Gqpre3EPUUgjg9cPQr7XylQg8NYSapsF0vYmRGwbjZYrmwBLPVaD4zCMS/24aeFuEhqeyl7hNwIBU61U7ymW pW9hgy5kd993nerGtCYPdOEMjVs EnJQt66AhjvwTA==&reflink=article_gmail_share

50. Armstrong, Mark. “Sudan military council receives aid from Saudi Arabia and UAE”, Reuters, April 21, 2019 https://www.euronews.com/2019/04/21/sudan-military-council-receives-aid-from-saudi-arabia-and-uae

51. Azar, Edward. The Management of Protracted Social Conflict: Theory & Cases, Aldershot, Dartmouth, 1990 p. 12.

52. Jaspers, Karl. The Origin and Goal of History (1st English ed.) Michael Bullock (Tr.), (London: Routledge, 1953), p. 51.